Temporal paradox

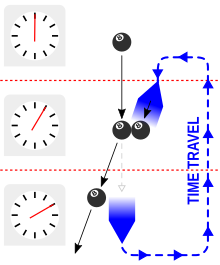

A temporal paradox, time paradox, or time travel paradox, is a paradox, an apparent contradiction, or logical contradiction associated with the idea of time travel or other foreknowledge of the future. While the notion of time travel to the future complies with the current understanding of physics via relativistic time dilation, temporal paradoxes arise from circumstances involving hypothetical time travel to the past – and are often used to demonstrate its impossibility.

Types

Temporal paradoxes fall into three broad groups: bootstrap paradoxes, consistency paradoxes, and Newcomb's paradox.

Bootstrap paradox

A boot-strap paradox, also known as an information loop, an information paradox,[6] an ontological paradox,[7] or a "predestination paradox" is a paradox of time travel that occurs when any event, such as an action, information, an object, or a person, ultimately causes itself, as a consequence of either retrocausality or time travel.[8][9][10][11]

Backward time travel would allow information, people, or objects whose histories seem to "come from nowhere".[8] Such causally looped events then exist in spacetime, but their origin cannot be determined.[8][9] The notion of objects or information that are "self-existing" in this way is often viewed as paradoxical.[9][6][12] Everett gives the movie Somewhere in Time as an example involving an object with no origin: an old woman gives a watch to a playwright who later travels back in time and meets the same woman when she was young, and gives her the same watch that she will later give to him.[6] An example of information which "came from nowhere" is in the movie Star Trek IV: The Voyage Home, in which a 23rd-century engineer travels back in time, and gives the formula for transparent aluminum to the 20th-century engineer who supposedly invented it.

Predestination paradox

Smeenk uses the term "predestination paradox" to refer specifically to situations in which a time traveler goes back in time to try to prevent some event in the past.[7]

Grandfather paradox

The consistency paradox or grandfather paradox occurs when the past is changed in any way, thus creating a contradiction. A common example given is traveling to the past and intervening with the conception of one's ancestors (such as causing the death of the parent beforehand), thus affecting the conception of oneself. If the time traveler were not born, then it would not be possible for them to undertake such an act in the first place. Therefore, the ancestor lives to offspring the time traveler's next-generation ancestor, and eventually the time traveler. There is thus no predicted outcome to this.[8] Consistency paradoxes occur whenever changing the past is possible.[9] A possible resolution is that a time traveller can do anything that did happen, but cannot do anything that did not happen. Doing something that did not happen results in a contradiction.[8] This is referred to as the Novikov self-consistency principle.

Variants

The grandfather paradox encompasses any change to the past,[13] and it is presented in many variations, including killing one's past self.[14][15] Both the "retro-suicide paradox" and the "grandfather paradox" appeared in letters written into Amazing Stories in the 1920s.[16] Another variant of the grandfather paradox is the "Hitler paradox" or "Hitler's murder paradox", in which the protagonist travels back in time to murder Adolf Hitler before he can instigate World War II and the Holocaust. Rather than necessarily physically preventing time travel, the action removes any reason for the travel, along with any knowledge that the reason ever existed.[17]

Physicist John Garrison et al. give a variation of the paradox of an electronic circuit that sends a signal through a time machine to shut itself off, and receives the signal before it sends it.[18][19]

Newcomb's paradox

Newcomb's paradox is a thought experiment showing an apparent contradiction between the expected utility principle and the strategic dominance principle.[20]

The thought experiment is often extended to explore causality and free will by allowing for "perfect predictors": if perfect predictors of the future exist, for example if time travel exists as a mechanism for making perfect predictions, then perfect predictions appear to contradict free will because decisions apparently made with free will are already known to the perfect predictor.[21][22] Predestination does not necessarily involve a supernatural power, and could be the result of other "infallible foreknowledge" mechanisms.[23] Problems arising from infallibility and influencing the future are explored in Newcomb's paradox.[24]

Proposed resolutions

Logical impossibility

Even without knowing whether time travel to the past is physically possible, it is possible to show using modal logic that changing the past results in a logical contradiction. If it is necessarily true that the past happened in a certain way, then it is false and impossible for the past to have occurred in any other way. A time traveler would not be able to change the past from the way it is; they would only act in a way that is already consistent with what necessarily happened.[25][26]

Consideration of the grandfather paradox has led some to the idea that time travel is by its very nature paradoxical and therefore logically impossible. For example, the philosopher Bradley Dowden made this sort of argument in the textbook Logical Reasoning, arguing that the possibility of creating a contradiction rules out time travel to the past entirely. However, some philosophers and scientists believe that time travel into the past need not be logically impossible provided that there is no possibility of changing the past,[13] as suggested, for example, by the Novikov self-consistency principle. Dowden revised his view after being convinced of this in an exchange with the philosopher Norman Swartz.[27]

Illusory time

Consideration of the possibility of backward time travel in a hypothetical universe described by a Gödel metric led famed logician Kurt Gödel to assert that time might itself be a sort of illusion.[28][29] He suggests something along the lines of the block time view, in which time is just another dimension like space, with all events at all times being fixed within this four-dimensional "block".[citation needed]

Physical impossibility

Sergey Krasnikov writes that these bootstrap paradoxes – information or an object looping through time – are the same; the primary apparent paradox is a physical system evolving into a state in a way that is not governed by its laws.[30]: 4 He does not find these paradoxical and attributes problems regarding the validity of time travel to other factors in the interpretation of general relativity.[30]: 14–16

Self-sufficient loops

A 1992 paper by physicists Andrei Lossev and Igor Novikov labeled such items without origin as Jinn, with the singular term Jinnee.[31]: 2311–2312 This terminology was inspired by the Jinn of the Quran, which are described as leaving no trace when they disappear.[32]: 200–203 Lossev and Novikov allowed the term "Jinn" to cover both objects and information with the reflexive origin; they called the former "Jinn of the first kind", and the latter "Jinn of the second kind".[6][31]: 2315–2317 [32]: 208 They point out that an object making circular passage through time must be identical whenever it is brought back to the past, otherwise it would create an inconsistency; the second law of thermodynamics seems to require that the object tends to a lower energy state throughout its history, and such objects that are identical in repeating points in their history seem to contradict this, but Lossev and Novikov argued that since the second law only requires entropy to increase in closed systems, a Jinnee could interact with its environment in such a way as to regain "lost" entropy.[6][32]: 200–203 They emphasize that there is no "strict difference" between Jinn of the first and second kind.[31]: 2320 Krasnikov equivocates between "Jinn", "self-sufficient loops", and "self-existing objects", calling them "lions" or "looping or intruding objects", and asserts that they are no less physical than conventional objects, "which, after all, also could appear only from either infinity or a singularity."[30]: 8–9

Novikov self-consistency principle

The self-consistency principle developed by

Physicist

Novikov's views are not widely accepted. Visser views causal loops and Novikov's self-consistency principle as an ad hoc solution, and supposes that there are far more damaging implications of time travel.[39] Krasnikov similarly finds no inherent fault in causal loops but finds other problems with time travel in general relativity.[30]: 14–16 Another conjecture, the cosmic censorship hypothesis, suggests that every closed timelike curve passes through an event horizon, which prevents such causal loops from being observed.[40]

Parallel universes

The interacting-multiple-universes approach is a variation of the many-worlds interpretation of quantum mechanics that involves time travelers arriving in a different universe than the one from which they came; it has been argued that, since travelers arrive in a different universe's history and not their history, this is not "genuine" time travel.[41] Stephen Hawking has argued for the chronology protection conjecture, that even if the MWI is correct, we should expect each time traveler to experience a single self-consistent history so that time travelers remain within their world rather than traveling to a different one.[42]

See also

- Quantum mechanics of time travel

- Fermi paradox

- Cosmic censorship hypothesis

- Retrocausality

- Wormhole

- Causality

- Causal structure

- Chronology protection conjecture

- Münchhausen trilemma

- Time loop

- Time travel in fiction

- Time travel

References

- ^ Jan Faye (November 18, 2015), "Backward Causation", Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, retrieved May 25, 2019

- ^ ISBN 9781439168486.

- ^ Ross, Kelley L. (1997). "Time Travel Paradoxes". Archived from the original on January 18, 1998.

- Bibcode:2003ntgp.conf..289L.

- ISBN 9780786478071.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-226-22498-5.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-19-929820-4

- ^ a b c d e Smith, Nicholas J.J. (2013). "Time Travel". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved June 13, 2015.

- ^ ISBN 1-4020-1200-4.

- ISBN 978-0-415-57441-9.

- ISBN 978-0-415-95826-4.

- ISBN 1-56396-653-0.

- ^ a b Nicholas J.J. Smith (2013). "Time Travel". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved November 2, 2015.

- ISBN 0262580888.

- ^ Jan Faye (November 18, 2015), "Backward Causation", Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, retrieved May 25, 2019

- ISBN 0-387-98571-9. Retrieved 2022-02-19.

- ISBN 9781567180855.

- S2CID 51796022.

- ISBN 9783319488622.

- S2CID 113227.

- S2CID 143485859.

- JSTOR 2027068.

- S2CID 143485859.

- ISBN 9780198240112.

- ^ Norman Swartz (2001), Beyond Experience: Metaphysical Theories and Philosophical Constraints, University of Toronto Press, pp. 226–227

- ISBN 0198236212.

- ^ Norman Swartz (1993). "Time Travel - Visiting the Past". SFU.ca. Retrieved 2016-04-21.

- ISBN 9780786737000. Retrieved December 18, 2017.

- ^ Holt, Jim (2005-02-21). "Time Bandits". The New Yorker. Retrieved 2017-12-13.

- ^ S2CID 18460829

- ^ S2CID 250912686. Archived from the original(PDF) on 17 November 2015. Retrieved 16 November 2015.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-393-06013-3.

- PMID 10013039.

- S2CID 16517920

- .

- ^ ISBN 0-393-31276-3.

- PMID 10013968.

- ^ ISBN 0-19-509591-X.

- ISBN 0-387-98571-9.

- S2CID 2869291.

- ^ Frank Arntzenius; Tim Maudlin (December 23, 2009), "Time Travel and Modern Physics", Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, retrieved May 25, 2019

- ^ Hawking, Stephen (1999). "Space and Time Warps". Archived from the original on February 10, 2012. Retrieved February 25, 2012.

- PMID 10013776.

- S2CID 208637445.

- S2CID 18597824.