Causes of seizures

Generally, seizures are observed in patients who do not have epilepsy.[1] There are many causes of seizures. Organ failure, medication and medication withdrawal, cancer, imbalance of electrolytes, hypertensive encephalopathy, may be some of its potential causes.[2] The factors that lead to a seizure are often complex and it may not be possible to determine what causes a particular seizure, what causes it to happen at a particular time, or how often seizures occur.[3]

Diet

Malnutrition and overnutrition may increase the risk of seizures.[4] Examples include the following:

- Vitamin B1 deficiency (thiamine deficiency) was reported to cause seizures, especially in alcoholics.[5][6][7]

- Vitamin B6 depletion (pyridoxine-dependent seizures.[8]

- Vitamin B12 deficiency was reported to be the cause of seizures for adults[9][10] and for infants.[11][12]

Medical conditions

Those with various medical conditions may experience seizures as one of their symptoms. These include:[citation needed]

- Aneurysm, especially of blood vessels in or near the brain, cranium (skull), and neck/upper spine

- Angelman syndrome

- Arteriovenous malformation

- Brain abscess

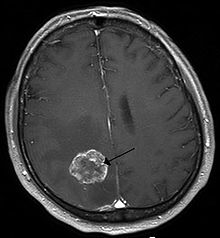

- Brain tumor

- Cavernoma

- Cerebral palsy

- Down syndrome

- Eclampsia, as well as other crises of pregnancy involving extreme hypertension or significant increases in intracranial pressure

- Epilepsy

- Encephalitis

- Fragile X syndrome

- Meningitis

- Multiple sclerosis

- Organ failure, especially of the brain, heart, lungs, liver, kidneys, and endocrine/exocrine organs- if it is severe enough and remains untreated and not fully corrected

- Stroke (both ischemic and hemorrhagic types)

- Systemic lupus erythematosus

- Tuberous sclerosis

Other conditions have been associated with lower seizure thresholds and/or increased likelihood of seizure comorbidity (but not necessarily with seizure induction). Examples include

Drugs

Adverse effect

Seizures may occur as an adverse effect of certain drugs. These include:[medical citation needed]

- Aminophylline

- Bupivicaine

- Bupropion

- Butyrophenones

- Caffeine (in high amounts of 500 mgs and above could increase the occurrence of seizures,[14] particularly if normal sleep patterns are interrupted)

- Chlorambucil

- Ciclosporin

- Clozapine

- Corticosteroids

- Diphenhydramine

- Enflurane

- Estrogens

- Fentanyl

- Insulin

- Lidocaine

- Maprotiline

- Meperidine

- Olanzapine

- Pentazocine

- Phenothiazines (such as chlorpromazine)

- Prednisone

- Procaine

- Propofol

- Propoxyphene

- Quetiapine

- Risperidone

- Sevoflurane

- Theophylline

- Tramadol

- Tricyclic antidepressants (especially clomipramine)

- Venlafaxine

- The following fluoroquinolones and carbapenems

Use of certain

If treated with the wrong kind of antiepileptic drugs (AED), seizures may increase, as most AEDs are developed to treat a particular type of seizure.

Convulsant drugs (the functional opposites of anticonvulsants) will always induce seizures at sufficient doses. Examples of such agents — some of which are used or have been used clinically and others of which are naturally occurring toxins — include strychnine, bemegride, flumazenil, cyclothiazide, flurothyl, pentylenetetrazol, bicuculline, cicutoxin, and picrotoxin.

Alcohol

There are varying opinions on the likelihood of alcoholic beverages triggering a seizure. Consuming alcohol may temporarily reduce the likelihood of a seizure immediately following consumption. But, after the blood alcohol content has dropped, chances may increase. This may occur, even in non-epileptics.[15]

Heavy drinking in particular has been shown to possibly have some effect on seizures in epileptics. But studies have not found light drinking to increase the likelihood of having a seizure at all.[

Consuming alcohol with food is less likely to trigger a seizure than consuming it without.[17]

Consuming alcohol while using many anticonvulsants may reduce the likelihood of the medication working properly. In some cases, it may trigger a seizure. Depending on the medication, the effects vary.[18]

Drug withdrawal

Some

, among others.Sudden withdrawal from anticonvulsants may lead to seizures. It is for this reason that if a patient's medication is changed, the patient will be weaned from the medication being discontinued following the start of a new medication.

Missed anticonvulsants

A

- Incorrect dosage amount: A patient may be receiving a sub-therapeutic level of the anticonvulsant.[22]

- Switching medicines: This may include withdrawal of anticonvulsant medication without replacement, replaced with a less effective medication, or changed too rapidly to another anticonvulsant. In some cases, switching from brand to a generic version of the same medicine may induce a breakthrough seizure.[23][24]

Fever

In children between the ages of 6 months and 5 years, a fever of 38 °C (100.4 °F) or higher may lead to a febrile seizure.[25] About 2-5% of all children will experience such a seizure during their childhood.[26] In most cases, a febrile seizure will not indicate epilepsy.[26] Approximately 40% of children who experience a febrile seizure will have another one.[26]

In those with epilepsy, fever can trigger a seizure. Additionally, in some, gastroenteritis, which causes vomiting and diarrhea, can lead to diminished absorption of anticonvulsants, thereby reducing protection against seizures.[27]

Vision

In some epileptics, flickering or flashing lights, such as

A routine part of the

Unlike photosensitive epilepsies – where epileptic activity only appears for few seconds after eye-closure – in some non-photosensitive epilepsies seizures may be triggered by the loss of central vision during eye-closure in an epileptic phenomenon called fixation-off sensitivity (FOS) where the epileptic activity persists for the total duration of eye-closure, though unrelated phenomena they can both coexist in some patients.[31][32][33]

Head injury

A severe

A brain injury can cause seizure(s) because of the unusual amount of energy that is discharged across of the brain when the injury occurs and thereafter. When there is damage to the temporal lobe of the brain, there is a disruption of the supply of oxygen.[35]

The risk of seizure(s) from a

Hyperglycemia and hypoglycemia

Hyperglycemia, or high blood sugar, can increase frequency of seizure. The probable mechanism is that elevated extracellular glucose level increases neuronal excitability.[38]

Curiously, hypoglycemia, or low blood sugar, can also trigger seizures.[39] The mechanism is also increased cortical excitability.[40]

Menstrual cycle

In catamenial epilepsy, seizures become more common during a specific period of the menstrual cycle.

Sleep deprivation

Sleep deprivation is the second most common trigger of seizures.[15] In some cases, it has been responsible for the only seizure a person ever has.[41] However, the reason for which sleep deprivation can trigger a seizure is unknown. One possible thought is that the amount of sleep one gets affects the amount of electrical activity in one's brain.[42]

Patients who are scheduled for an EEG test are asked to deprive themselves of some sleep the night before to be able to determine if sleep deprivation may be responsible for seizures.[43]

In some cases, patients with epilepsy are advised to sleep 6-7 consecutive hours as opposed to broken-up sleep (e.g., 6 hours at night and a 2-hour nap) and to avoid

Parasites and stings

In some cases, certain

, and many other parasitic diseases can cause seizures.Seizures have been associated with insect stings. Reports suggest that patients stung by red imported fire ants (Solenopsis invicta) and Polistes wasps had seizures because of the venom.[45][46]

In endemic areas,

Stress

Stress can induce seizures in people with epilepsy, and is a risk factor for developing epilepsy. Severity, duration, and time at which stress occurs during development all contribute to frequency and susceptibility to developing epilepsy. It is one of the most frequently self-reported triggers in patients with epilepsy.[48][49]

Stress exposure results in

"Epileptic fits" as a result of stress are common in literature and frequently appear in Elizabethan texts, where they are referred to as the "falling sickness".[51]

Breakthrough seizure

A breakthrough seizure is an

Breakthrough seizures vary. Studies have shown the rates of breakthrough seizures ranging from 11 to 37%.[56] Treatment involves measuring the level of the anticonvulsant in the patient's system and may include increasing the dosage of the existing medication, adding another medication to the existing one, or altogether switching medications.[57] A person with a breakthrough seizure may require hospitalization for observation.[52]: 498

Other

- absorption of the anticonvulsant.[54]: 67

- Malnutrition: May be the result of poor dietary habits, lack of access to proper nourishment, or fasting.[54]: 68 In seizures that are controlled by diet in children, a child may break from the diet on their own.[58]

Music (as in musicogenic epilepsy) [59][60][61]

Diagnosis and management

In the case of patients with seizures associated with medical illness, the patients are firstly stabilized. They are attended to their circulation, airway, and breathing. Next vital signs are assessed through a monitor, intravenous access is obtained, and concerning laboratory tests are performed.

References

- S2CID 42324759.

- ^ S2CID 42324759.

- ^ "Epilepsy Foundation".

- ISBN 978-0-19-803152-9.

- ^ 100 Questions & Answers About Epilepsy, Anuradha Singh, page 79

- PMID 2044623.

- S2CID 16976274.

- ^ Vitamin B-6 Dependency Syndromes at eMedicine

- PMID 19462816.

- PMID 15069260.

- ^ Mustafa TAŞKESEN; Ahmet YARAMIŞ; Selahattin KATAR; Ayfer GÖZÜ PİRİNÇÇİOĞLU; Murat SÖKER (2011). "Neurological presentations of nutritional vitamin B12 deficiency in 42 breastfed infants in Southeast Turkey" (PDF). Turk J Med Sci. 41 (6). TÜBİTAK: 1091–1096. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-12-14. Retrieved 2014-10-01.

- S2CID 9565203.

- PMID 15309159.

- ISBN 9781888799897.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-7817-5777-5.

- ISBN 978-1-888799-34-7.

- ^ "Epilepsy Foundation".

- ISBN 978-1-888799-34-7.

- ISBN 978-1-934559-91-8.

- ISBN 978-1-934559-91-8.

- ISBN 978-0-7817-7153-5.

missed doseseizure.

- ISBN 9780071377508.

- ISBN 9780763755218.

- S2CID 44324824.

- ISBN 978-0071759052.

- ^ PMID 22335215.

- ISBN 978-1-934559-91-8.

- ISBN 978-0-7817-7397-3.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-898683-02-5.

- ^ "Flickering light and seizurs". Pediatrics for Parents. March 2005. Archived from the original on 2012-07-09 – via FindArticles.

- PMID 28993753. Retrieved November 19, 2022.

- S2CID 221125236. Retrieved November 19, 2022.

- ISBN 9780340808146.

- ^ Overview of Head Injuries: Head Injuries Merck Manual Home Edition

- ISBN 978-0-89529-791-4.

- ISBN 978-0-86577-727-9.

- ^ "Head Injury as a Cause of Epilepsy". EpilepsyFoundation.org. Archived from the original on 2011-06-23. Retrieved 2011-06-23. Epilepsy Foundation

- PMID 15309063.

- PMID 17702035.

- S2CID 7207035.

- ^ "Can sleep deprivation trigger a seizure?". epilepsy.com. Archived from the original on 2013-10-29. Retrieved 2013-10-29.

- ISBN 978-1-934559-91-8.

- ISBN 978-1-932603-20-0.

- ISBN 978-1-934559-91-8.

- PMID 8241804.

- PMID 8844507.

- PMID 24551255.

- S2CID 36696690.

- S2CID 27433395.

- PMID 28916130.

- S2CID 31281356.

- ^ ISBN 9780763744052.

- .

- ^ ISBN 9781932603415.

- ISBN 9780683307238.

- ISBN 9781933864167.

- ISBN 9780781757775.

- ISBN 9781932603187.

- PMID 25726285.

- ^ "music and epilepsy". Epilepsy Society. 2015-08-10. Retrieved 2017-09-16.

- S2CID 33600372.