Celadon

| Celadon | ||

|---|---|---|

Hanyu Pinyin qīngcí | | |

| IPA | [tɕʰíŋtsʰɹ̩̌] | |

| Yue: Cantonese | ||

| Yale Romanization | chēngchìh | |

| Jyutping | ceng1-ci4 | |

| IPA | [tsʰɛːŋ˥tsʰiː˩] | |

Celadon (/ˈsɛlədɒn/) is a term for pottery denoting both wares glazed in the jade green celadon color, also known as greenware or "green ware" (the term specialists now tend to use),[1] and a type of transparent glaze, often with small cracks, that was first used on greenware, but later used on other porcelains. Celadon originated in China, though the term is purely European, and notable kilns such as the Longquan kiln in Zhejiang province are renowned for their celadon glazes.[2] Celadon production later spread to other parts of East Asia, such as Japan and Korea,[3] as well as Southeast Asian countries, such as Thailand. Eventually, European potteries produced some pieces, but it was never a major element there. Finer pieces are in porcelain, but both the color and the glaze can be produced in stoneware and earthenware. Most of the earlier Longquan celadon is on the border of stoneware and porcelain, meeting the Chinese but not the European definitions of porcelain.

For many centuries, celadon wares were highly regarded by the Chinese imperial court, before being replaced in fashion by painted wares, especially the new

The celadon color is classically produced by firing a glaze containing a little iron oxide at a high temperature in a reducing kiln. The materials must be refined, as other chemicals can alter the color completely. Too little iron oxide causes a blue color (sometimes a desired effect), and too much gives olive and finally black; the right amount is between 0.75% and 2.5%. The presence of other chemicals may have effects; titanium dioxide gives a yellowish tinge.[4]

Etymology

The term "celadon" for the pottery's pale

Production and characteristics

Celadon glaze refers to a family of usually partly transparent but colored glazes, many with pronounced (and sometimes accentuated) "crackle", or tiny cracks in the glaze produced in a wide variety of colors, generally used on stoneware or porcelain pottery bodies.

So-called "true celadon", which requires a minimum 1,260 °C (2,300 °F) furnace temperature, a preferred range of 1,285 to 1,305 °C (2,345 to 2,381 °F), and firing in a

Celadon glazes can be produced in a variety of colors, including white, grey, blue and yellow, depending on several factors:

- the thickness of the applied glaze,

- the type of clay to which it is applied,

- the exact chemical makeup of the glaze,

- the firing temperature

- the degree of reduction in the kiln atmosphere and

- the degree of opacity in the glaze.

The most famous and desired shades range from a very pale green to deep intense green, often meaning to mimic the green shades of jade. The main color effect is produced by

East Asia

Chinese celadons

Greenwares are found in earthenware from the

The earliest major type of celadon was

All the wares mentioned above were mostly in, or aiming to be in, some shade of green. Other wares which can be classified as celadons, were more often in shades of pale blue, very highly valued by the Chinese, or various browns and off-whites. These were often the most highly regarded at the time and by later Chinese connoisseurs, and sometimes made more or less exclusively for the court. These include Ru ware, Guan ware and Ge ware,[13] as well as earlier types such as the "secret color" (mi se) wares,[14] finally identified when the crypt at the Famen Temple was opened.

Large quantities of Longquan celadon were exported throughout East Asia, Southeast Asia and the Middle East in the 13th–15th century. Large celadon dishes were especially welcomed in Islamic nations. Since about 1420 the Counts of

Decoration in Chinese celadons is normally only by shaping the body or creating shallow designs on the flat surface which allow the glaze to pool in depressions, giving a much deeper color to accentuate the design. In both methods carving, moulding and a range of other techniques may be used. There is very rarely any contrast with a completely different color, except where parts of a piece are sometimes left as unglazed biscuit in Longquan celadon.

-

Western Jin, Zhejiang.

-

Yaozhou ware (Northern Celadon), with carved and engraved decoration, 10th century.

-

Yaozhou ware, Shaanxi province, Song dynasty, 10th–11th century

-

Centre areas left unglazed in 'biscuit state', 14th century.

-

Warming Bowl in the Shape of a Flower with Light Bluish-green Glaze, Ru ware

-

Guan ware, Southern Song dynasty, 1100s–1200s AD

-

Flower vase with Iron Brown Spots (飛青磁花生), Longquan kiln, Yuan dynasty, 13–14th century (National Treasure)

-

Longquan celadon from Zhejiang, Ming dynasty, 14–15th century

-

Ewer, lidded tripod with handles, used for heating certain alcoholic drinks. Stoneware with pale green (celadon) glaze. Six Dynasties, 500-580 CE. Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Japanese celadons

The Japanese pronunciation of the Chinese characters for greenware is seiji (青磁). It was introduced during the Song dynasty (960–1270) from China and via Korea. Even though Japan has arguably the most diverse styles of ceramic art in the modern era, greenware was mostly avoided by potters because of the high loss rate of up to 80%.[17] Kaolinite, the ceramic material usually used for the production of porcelain, also does not exist in large quantities like in China. One of the sources for kaolin in Japan is from Amakusa in Kyushu. Nevertheless, a number of artists emerged whose works received critical acclaim in regards to the quality and color of the glazes achieved, as well as later on in the innovation of modern design.

Three pieces originally from China have been registered by the government as national treasures. They are two flower vases from the Longquan kiln dating to the southern Song dynasty in the 13th century, and a flower vase with iron brown spots also from Longquan kiln dating to the Yuan dynasty in the 13–14th century.

Production in the style of Longquan was centered around Arita, Saga and in the Saga Domain under the lords of the Nabeshima clan.[18] Greenware is also closed entwined with hakuji (白磁) white porcelain. The glaze with a mixed subtle color gradations of icy, bluish white is called seihakuji (青白磁) porcelain.[19] In Chinese this type of glaze is known as Qingbai ware.[20] Qingbai's history goes back to the Song dynasty. It is biscuit-fired and painted with a glaze containing small amounts of iron. This turns a bluish color when fired again. Japanese artists and clients tend to favor the seihakuji bluish white glaze over the completely green glaze.[18]

Pieces that are produced are normally tea or rice bowls, sake cups, vases, and plates, and mizusashi water jars for tea ceremony, censers and boxes. Some post-modern ceramic artists have however expanded into the area of sculpture and abstract art as well.

Artists from the early Showa era are Itaya Hazan (1872–1963), Tomimoto Kenkichi (1886–1963), Kato Hajme (1900–1968), Tsukamoto Kaiji (塚本快示) (1912–1990), and Okabe Mineo (1919–1990), who specialized in

Artists such as Fukami Sueharu, Masamichi Yoshikawa, and Kato Tsubusa also produce abstract pieces, and their works are part of a number of national and international museum collections.[24] Kato Tsubusa works with kaolin from New Zealand.[25]

Korean celadons

Korean celadon has its own tradition of greenware production, dating back to the Three Kingdoms period. Korea has a tradition of making jewels and crowns with jade in

Korean greenware, also known as "Goryeo celadon" is usually a pale green-blue in color. The glaze was developed and refined during the 10th and 11th centuries during the Goryeo period, from which it derives its name. Korean greenware reached its zenith between the 12th and early 13th centuries, however, the Mongol invasions of Korea in the 13th century and persecution by the Joseon dynasty government destroyed the craft.[citation needed]

The

Traditional Korean greenware has distinctive decorative elements. The most distinctive are decorated by overlaying glaze on contrasting clay bodies. With inlaid designs, known as sanggam in Korean, small pieces of colored clay are inlaid in the base clay. Carved or slip-carved designs require layers of a different colored clay adhered to the base clay of the piece. The layers are then carved away to reveal the varying colors.

A number of items dating from the Goryeo dynasty have been registered by the government as a

Beginning in the early 20th century, potters, using modern materials and tools, attempted to recreate the techniques of ancient Korean Goyeo celadons. Playing a leading role in its revival was Yu Geun-Hyeong (유근형; 柳根瀅), a Living National Treasure whose work was documented in the 1979 short film, Koryo Celadon. Another notable potter and Living National Treasure was Ji Suntaku (1912–1993). Today, hundreds of potters showcase their work at the Icheon Ceramics Village, which features contemporary work from Sugwang-ri, Sindun-myeon, and Saeum-dong in the city of Icheon.[29]

The National Museum of Korea in Seoul houses important celadon works and national treasures. The Haegang Ceramics Museum and the Goryeo Celadon Museum are two regional museums that focus on Korean greenware.

-

Dragon turtle kettle, Goryeo dynasty, 12th century (National Treasure No. 61)

-

Maebyeong vase with sanggam engraved cranes, hand carved 12th century Goryeo dynasty, (National Treasure No. 68)

-

�Goryeo dynasty bowl with sanggam inlay

-

Goryeo celadon incense burner with Girin mystic sacred animal lid on it

-

Goryeo celadon of Korean Chamoe (yellow water melon) shaped motif, 12th century

-

tea cup with flower inlays, Goryeo dynasty

-

horibyeong, Korea celadon of Goryeo period

-

creative design of baby bamboo, virtue for scholars, water dropper for calligraphy, Seoye

-

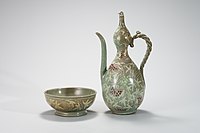

Goryeo celadon ewer or tea pot inside a cup

-

a step to the white porcelain, Goryeo celadon

-

Pitcher in the shape of aDragon Turtle, Goryeo dynasty, (National Treasure No. 96)

-

inlay carved tea cup with silver lining, Goryeo celadon

-

incense burner, Goryeo Celadon

-

incense burner of Goryeo, celadon

-

pillow, celadon

-

celadon hand-carved inlaid and colored red, decorated with grapes

-

Goryeo incense keeping case hand carved and inlaid with white and black, white cranes decorated

-

Korea Goryeo dynasty object of a seated immortal

-

Korean water melon Chamowe shape tea pot or ewer became popular

-

Celadon chairs, objects for calligraphy ceremony Seoye

-

lighter glazed tea cup Goryeo celadon, incised parrot

-

celadon vase, Goryeo period

-

aromatic oil container with four other incense boxed

-

molded and carved lotus, Gangjin kilns, 1100–1250 celadon

-

face washing plate called sesoodaeya, Goryeo celadon

-

Lidded Jar, Joseon dynasty (National Treasure No. 1071)

-

Goryeo celadon incense burner with duck lid on, 12th century, duck symbolizes a sacred guide to the sky on the way across a hwangcheon river after death

Southeast Asia

Thai celadon

-

Bowl with incised peony designs, Sri Satchanalai, 15th century

-

Bottle with two shoulder lugs, Sawankhalok, 15th century

Vietnamese celadon

-

Teapot, Lý dynasty period, 11th–12th century

-

Tea cup, Lý dynasty period, 11th–12th century

-

Green celadon jar, Trần dynasty period, 14th century

Others

Outside of East Asia a number of artists also worked with greenware to varying degrees of success in regards to purity and quality. These include

Notes

- ^ British Museum glossary; Christie's Collector's Guide; this is not to be confused with "greenware", meaning unfired clay pottery, as a stage of production.

- ^ "Chinese Porcelain Glossary: Celadon". Gotheborg.com. Retrieved 2017-03-17.

- ^ "Goryeo Celadon | Essay | Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History". The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 2017-03-17.

- ^ ISBN 9780714114705.

- ^ Gompertz, 21

- ^ Dennis Krueger. "Why On Earth Do They Call It Throwing?" Archived 2007-02-03 at the Wayback Machine from Ceramics Today

- ^ ISBN 0-8122-1837-X, p. 42.

- ISBN 0-300-02723-0.

- ^ Gompertz, Ch. 1

- ^ Gompertz, Ch. 4

- ^ Gompertz, Ch. 6

- ISBN 0-8122-3476-6, pp. 75–76.

- ^ Gompertz, Ch. 4 and 5

- ^ Gompertz, Ch. 3

- ^ "Katzenelnbogener Weltrekorde: Erster RIESLING und erste BRATWURST!". Graf-von-katzenelnbogen.com. Retrieved 2017-03-17.

- ^ Gompertz, Ch. 7 & 8

- ^ a b "CELADON Menu – EY Net Japanese Pottery Primer". E-yakimono.net. Retrieved 2017-03-17.

- ^ a b "Ambient Green Flow _ 青韻流動". Exhibition.ceramics.ntpc.gov.tw. Archived from the original on 2015-07-07. Retrieved 2017-03-17.

- ^ "PORCELAIN Menu – EY Net Japanese Pottery Primer". E-yakimono.net. Retrieved 2017-03-17.

- ^ ""Pure-pure" Seihakuji bowl | Herbert F. Johnson Museum of Art". Museum.cornell.edu. Retrieved 2016-09-17.

- ^ "Yoshikawa Masamichi – Artists – Joan B Mirviss LTD | Japanese Fine Art". Mirviss.com. Retrieved 2017-03-17.

- ^ "Kawase Shinobu, Japanese Celadon Artist". E-yakimono.net. 2000-04-19. Retrieved 2017-03-17.

- ^ "Minegishi Seiko, Celadon Artist from Japan". E-yakimono.net. Retrieved 2017-03-17.

- ^ "Collection | The Metropolitan Museum of Art". Metmuseum.org. Retrieved 2017-03-17.

- ^ "Kato Tsubusa – White Porcelain Artist". E-yakimono.net. Retrieved 2017-03-17.

- ^ a b "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2016-04-14. Retrieved 2019-11-02.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ International, Rotary (December 1988). The Rotarian. p. 15. Retrieved 2017-03-17.

- ISBN 9780521838337. Retrieved 2017-03-17.

- ^ "Icheon Ceramics Village (이천도예마을)". English.visitkorea.or.kr. Retrieved 2017-03-17.

- ISBN 1-878529-70-6, S. 56–80.

References

- Gompertz, G. St. G. M., Chinese Celadon Wares, 1980 (2nd ed.), Faber & Faber, ISBN 0571180035.

Further reading

- Korean art from the Gompertz and other collections in the Fitzwilliam Museum, by Yong-i Yun, Regina Krahl

- Valenstein, Suzanne G. (1975): A Handbook of Chinese Ceramics. The Metropolitan Museum of Art.