Cell division

Cell division is the process by which a parent

For simple unicellular microorganisms such as the amoeba, one cell division is equivalent to reproduction – an entire new organism is created. On a larger scale, mitotic cell division can create progeny from multicellular organisms, such as plants that grow from cuttings. Mitotic cell division enables sexually reproducing organisms to develop from the one-celled zygote, which itself is produced by fusion of two gametes, each having been produced by meiotic cell division.[5][6] After growth from the zygote to the adult, cell division by mitosis allows for continual construction and repair of the organism.[7] The human body experiences about 10 quadrillion cell divisions in a lifetime.[8]

The primary concern of cell division is the maintenance of the original cell's genome. Before division can occur, the genomic information that is stored in chromosomes must be replicated, and the duplicated genome must be cleanly divided between progeny cells.[9] A great deal of cellular infrastructure is involved in ensuring consistency of genomic information among generations.[10][11][12]

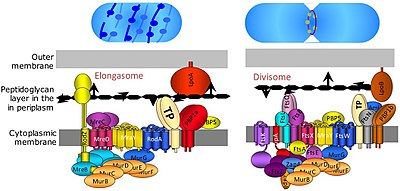

In bacteria

Bacterial cell division happens through binary fission or sometimes through budding. The divisome is a protein complex in bacteria that is responsible for cell division, constriction of inner and outer membranes during division, and remodeling of the peptidoglycan cell wall at the division site. A tubulin-like protein, FtsZ plays a critical role in formation of a contractile ring for the cell division.[14]

In eukaryotes

Cell division in eukaryotes is more complicated than in prokaryotes. If the chromosomal number is reduced, eukaryotic cell division is classified as meiosis (reductional division). If the chromosomal number is not reduced, eukaryotic cell division is classified as mitosis (equational division). A primitive form of cell division, called amitosis, also exists. The amitotic or mitotic cell divisions are more atypical and diverse among the various groups of organisms, such as protists (namely diatoms, dinoflagellates, etc.) and fungi.

In the mitotic metaphase (see below), typically the chromosomes (each containing 2 sister chromatids that developed during replication in the S phase of interphase) align themselves on the metaphase plate. Then, the sister chromatids split and are distributed between two daughter cells.

In meiosis I, the homologous chromosomes are paired before being separated and distributed between two daughter cells. On the other hand, meiosis II is similar to mitosis. The

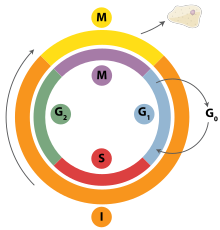

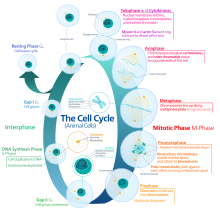

Phases of eukaryotic cell division

Interphase

Prophase

Prometaphase

Prometaphase is the second stage of cell division. This stage begins with the complete breakdown of the nuclear envelope which exposes various structures to the cytoplasm. This breakdown then allows the spindle apparatus growing from the centrosome to attach to the kinetochores on the sister chromatids. Stable attachment of the spindle apparatus to the kinetochores on the sister chromatids will ensure error-free chromosome segregation during anaphase.[24] Prometaphase follows prophase and precedes metaphase.

Metaphase

In metaphase, the centromeres of the chromosomes align themselves on the metaphase plate (or equatorial plate), an imaginary line that is at equal distances from the two centrosome poles and held together by complexes known as cohesins. Chromosomes line up in the middle of the cell by microtubule organizing centers (MTOCs) pushing and pulling on centromeres of both chromatids thereby causing the chromosome to move to the center. At this point the chromosomes are still condensing and are currently one step away from being the most coiled and condensed they will be, and the spindle fibers have already connected to the kinetochores.[25] During this phase all the microtubules, with the exception of the kinetochores, are in a state of instability promoting their progression toward anaphase.[26] At this point, the chromosomes are ready to split into opposite poles of the cell toward the spindle to which they are connected.[27]

Anaphase

Telophase

Telophase is the last stage of the cell cycle in which a cleavage furrow splits the cells cytoplasm (cytokinesis) and chromatin. This occurs through the synthesis of a new nuclear envelope that forms around the chromatin gathered at each pole. The nucleolus reforms as the chromatin reverts back to the loose state it possessed during interphase.[32][33] The division of the cellular contents is not always equal and can vary by cell type as seen with oocyte formation where one of the four daughter cells possess the majority of the duckling.[34]

Cytokinesis

The last stage of the cell division process is cytokinesis. In this stage there is a cytoplasmic division that occurs at the end of either mitosis or meiosis. At this stage there is a resulting irreversible separation leading to two daughter cells. Cell division plays an important role in determining the fate of the cell. This is due to there being the possibility of an asymmetric division. This as a result leads to cytokinesis producing unequal daughter cells containing completely different amounts or concentrations of fate-determining molecules.[35]

In animals the cytokinesis ends with formation of a contractile ring and thereafter a cleavage. But in plants it happen differently. At first a cell plate is formed and then a cell wall develops between the two daughter cells.[citation needed]

In Fission yeast (S. pombe) the cytokinesis happens in G1 phase. [36]

Variants

Cells are broadly classified into two main categories: simple non-nucleated

In 2022, scientists discovered a new type of cell division called asynthetic fission found in the squamous epithelial cells in the epidermis of juvenile zebrafish. When juvenile zebrafish are growing, skin cells must quickly cover the rapidly increasing surface area of the zebrafish. These skin cells divide without duplicating their DNA (the S phase of mitosis) causing up to 50% of the cells to have a reduced genome size. These cells are later replaced by cells with a standard amount of DNA. Scientists expect to find this type of division in other vertebrates.[38]

DNA Damage Repair in the Cell Cycle

DNA damage is detected and repaired at various points in the cell cycle. The G1/S checkpoint, G2/M checkpoint, and the checkpoint between metaphase and anaphase all monitor for DNA damage and halt cell division by inhibiting different cyclin-CDK complexes. The p53 tumor-suppressor protein plays a crucial role at the G1/S checkpoint and the G2/M checkpoint. Activated p53 proteins result in the expression of many proteins that are important in cell cycle arrest, repair, and apoptosis. At the G1/S checkpoint, p53 acts to ensure that the cell is ready for DNA replication, while at the G2/M checkpoint p53 acts to ensure that the cells have properly duplicated their content before entering mitosis. [39]

Specifically, when DNA damage is present,

If DNA is damaged, the cell can also alter the Akt pathway in which BAD is phosphorylated and dissociated from Bcl2, thus inhibiting apoptosis. If this pathway is altered by a loss of function mutation in Akt or Bcl2, then the cell with damaged DNA will be forced to undergo apoptosis. [43] If the DNA damage cannot be repaired, activated p53 can induce cell death by apoptosis. It can do so by activating the p53 upregulated modulator of apoptosis (PUMA). PUMA is a pro-apoptotic protein that rapidly induces apoptosis by inhibiting the anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 family members.[44]

Degradation

Multicellular organisms replace worn-out cells through cell division. In some animals, however, cell division eventually halts. In

History

A cell division under

In 1943, cell division was filmed for the first time[49] by Kurt Michel using a phase-contrast microscope.[50]

See also

- Cell fusion

- Cell growth

- Cyclin-dependent kinase

- Labile cells, cells that constantly divide

- Mitotic catastrophe

References

- OCLC 176818780.

- OCLC 698085201.

- ^ "10.2 The Cell Cycle – Biology 2e | OpenStax". openstax.org. 28 March 2018. Retrieved 2020-11-24.

- ^ Gilbert, Scott F. (2000), "Meiosis", Developmental Biology. 6th edition, Sinauer Associates, retrieved 2023-09-08

- ^ Gilbert SF (2000). "Spermatogenesis". Developmental Biology (6th ed.). Sinauer Associates.

- ^ Gilbert SF (2000). "Oogenesis". Developmental Biology (6th ed.). Sinauer Associates.

- OCLC 37049921.

- ISSN 0017-789X. Retrieved 2019-04-14.

- OCLC 669515286.

- PMID 20110992.

- PMID 25964792.

- PMID 31003495.

- PMID 27767957.

- ^ Cell Division: The Cycle of the Ring, Lawrence Rothfield and Sheryl Justice, CELL, DOI

- OCLC 41266267.

- PMID 2683075.

- PMID 11063129.

- OCLC 70173205.

- PMID 17472438.

- S2CID 5530166.

- PMID 18535242.

- ^ Lewontin RC, Miller JH, Gelbart WM, Griffiths AJ (1999). "The Mechanism of Crossing-Over". Modern Genetic Analysis.

- PMID 11529427.

- ^ "Prometaphase – an overview | ScienceDirect Topics". www.sciencedirect.com. Retrieved 2023-11-21.

- ^ "Researchers Shed Light On Shrinking Of Chromosomes". ScienceDaily. Retrieved 2019-04-14.

- ^ a b Walter P, Roberts K, Raff M, Lewis J, Johnson A, Alberts B (2002). "Mitosis". Molecular Biology of the Cell (4th ed.). Garland Science.

- OCLC 473440643.

- PMID 24906316.

- ^ "The Cell Cycle". www.biology-pages.info. Retrieved 2019-04-14.

- ISBN 978-0-321-81380-0.

- PMID 22084387.

- PMID 25435919.

- PMID 20300205.

- ^ Gilbert SF (2000). "Oogenesis". Developmental Biology (6th ed.). Sinauer Associates.

- PMID 12040122.

- ^ The Cell, G.M. Cooper; ed 2 NCBI bookshelf, The eukaryotic cell cycle, Figure 14.7

- Internet archive. Archived from the originalon 29 June 2013.

- S2CID 248416916.

- PMID 23150436.

- PMID 32183020.

- PMID 27048304.

- PMID 35361964.

- S2CID 2079715.

- PMID 19079139.

- PMID 18695223.

- S2CID 38437955.

- PMID 27323951.

- ^ Biographie, Deutsche. "Mohl, Hugo von – Deutsche Biographie". www.deutsche-biographie.de (in German). Retrieved 2019-04-15.

- ISBN 978-0470016176.

- ^ ZEISS Microscopy (2013-06-01), Historic time lapse movie by Dr. Kurt Michel, Carl Zeiss Jena (ca. 1943), archived from the original on 2021-11-07, retrieved 2019-04-15

Further reading

- Morgan HI. (2007). "The Cell Cycle: Principles of Control" London: New Science Press.

- J.M.Turner Fetus into Man (1978, 1989). Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-30692-9

- Cell division: binary fission and mitosis

- McDougal, W. Scott, et al. Campbell-Walsh Urology Eleventh Edition Review. Elsevier, 2016.

- The Mitosis and Cell Cycle Control Section from the Landmark Papers in Cell Biology (Gall JG, McIntosh JR, eds.) contains commentaries on and links to seminal research papers on mitosis and cell division. Published online in the Image & Video Library of The American Society for Cell Biology

- The Image & Video Library Archived 2011-06-10 at the Wayback Machine of The American Society for Cell Biology contains many videos showing the cell division.

- The Cell Division of the Cell Image Library

- Images : Calanthe discolor Lindl. – Flavon's Secret Flower Garden

- Tyson's model of cell division and a Description on BioModels Database

- WormWeb.org: Interactive Visualization of the C. elegans Cell Lineage – Visualize the entire set of cell divisions of the nematode C. elegans