Chahamanas of Shakambhari

Chahamanas of Shakambhari | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6th century–1192 | |||||||||||||

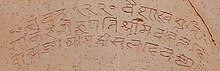

Coin of the Chahamana ruler Vigraharaja IV, c. 1150 – c. 1164. Obverse: Rama standing left, holding bow; "sri ra ma" in Devanagari. Reverse: "Srimad vigra/ha raja de/va" in Devanagari; star and moon symbols below.

| |||||||||||||

![Approximate territory of the Chahamanas of Shakambhari circa 1150–1192 CE.[1]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/de/Map_of_the_Cahamanas.png/300px-Map_of_the_Cahamanas.png) Approximate territory of the Chahamanas of Shakambhari circa 1150–1192 CE.[1] | |||||||||||||

| Capital | |||||||||||||

| Religion | Hinduism | ||||||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||||||

• 6th century | Vasudeva (first) | ||||||||||||

• c. 1193–1194 CE | Hariraja (last) | ||||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||||

• Established | 6th century | ||||||||||||

| 1192 | |||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| Today part of | India | ||||||||||||

The Chahamanas of Shakambhari (

The Chahamanas originally had their capital at

The Chahamanas fought several wars with their neighbours, including the

.Origin

According to the 1170 CE

Several mythical accounts of the dynasty's origin also exist. The earliest of the dynasty's inscriptions and literary works state that the dynasty's progenitor was a legendary hero named Chahamana. They variously state that this hero was born from

Territory

The core territory of the Chahamanas was located in present-day

The term Jangladesha ("rough and arid country") appears to be older, as it mentioned in the Mahabharata.[10] The text does not mention the exact location of the region. The later Sanskrit texts, such as Bhava Prakasha and Shabdakalpadruma Kosha suggest that it was a hot, arid region, where trees requiring little water grew. The region is identified with the area around Bikaner.[11]

The term Sapadalaksha (literally "one and a quarter lakhs" or 125,000) refers to the large number of villages in the area.[12] It became prominent during the Chahamana reign. It appears that the term originally referred to the area around modern Nagaur near Bikaner. This area was known as Savalak (vernacular form of Sapadalaksha) in as late as 20th century.[10] The early Chahamana king Samantaraja was based in Ahichchhatrapura, which can be identified with modern Nagaur. The ancient name of Nagaur was Nagapura, which means "the city of the serpent". Ahichchhatrapura has a similar meaning: "the city whose chhatra or protector is serpent".[13]

As the Chahamana territory expanded, the entire region ruled by them came to be known as Sapadalaksha.

History

The earliest historical Chahamana king is the 6th century ruler

Simharaja's successors consolidated the Chahamana power by engaging in wars with their neighbours, including the

The subsequent Chahamana kings faced several

Arnoraja's younger son

Vigraharaja was succeeded by his son Amaragangeya, and then his nephew Prithviraja II. Subsequently, his younger brother Someshvara ascended the throne.[27]

The most celebrated ruler of the dynasty was Someshvara's son Prithviraja III, better known as

Muhammad of Ghor appointed Prithviraja's son Govindaraja IV as a vassal. Prithviraja's brother Hariraja dethroned him, and regained control of a part of his ancestral kingdom. Hariraja was defeated by the Ghurids in 1194 CE. Govindaraja was granted the fief of Ranthambore by the Ghurids. There, he established a new branch of the dynasty.[30]

Cultural activities

The Chahamanas commissioned a number of Hindu temples, several of which were destroyed by the

Multiple Chahamana rulers contributed to the construction of the

- Simharaja commissioned a large Shiva temple at Pushkar[33]

- Chamundaraja commissioned a Vishnu temple at Narapura (modern Narwar in Ajmer district)[34]

- Prithviraja I built a food distribution centre (anna-satra) on the road to Somnath temple for pilgrims.[35]

- Someshvara commissioned a number of temples, including five temples in Ajmer.[36][37]

The Chahamana rulers also patronized Jainism. Vijayasimha Suri's Upadeśāmālavritti (1134 CE) and Chandra Suri's Munisuvrata-Charita (1136 CE) state that Prithviraja I donated golden kalashas (cupolas) for the Jain temples at Ranthambore.[39] The Kharatara-Gachchha-Pattavali states that Ajayaraja II allowed the Jains to build their temples in his capital Ajayameru (Ajmer), and also donated a golden kalasha to a Parshvanatha temple.[40] Someshvara granted the Revna village to a Parshvanatha temple.[36]

List of rulers

Following is a list of Chahamana rulers of Shakambhari and Ajmer, with approximate period of reign, as estimated by R. B. Singh:[43]

| # | Ruler | Reign (CE) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Chahamana

|

(mythical) |

| 2 | Vasu-deva | c. 551 CE (disputed) |

| 3 | Samanta-raja | 684–709 |

| 4 | Nara-deva | 709–721 |

| 5 | Ajaya-raja I | 721–734 |

| 6 | Vigraha-raja I | 734–759 |

| 7 | Chandra-raja I | 759–771 |

| 8 | Gopendra-raja | 771–784 |

| 9 | Durlabha-raja I | 784–809 |

| 10 | Govinda-raja I alias Guvaka I | 809–836 |

| 11 | Chandra-raja II | 836–863 |

| 12 | Govindaraja II alias Guvaka II | 863–890 |

| 13 | Chandana-raja | 890–917 |

| 14 | Vakpati-raja | 917–944 |

| 15 | Simha-raja | 944–971 |

| 16 | Vigraha-raja II | 971–998 |

| 17 | Durlabha-raja II | 998–1012 |

| 18 | Govinda-raja III | 1012–1026 |

| 19 | Vakpati-raja II | 1026–1040 |

| 20 | Viryarama | 1040 (few months) |

| 21 | Chamunda-raja | 1040–1065 |

| 22 | Durlabha-raja III alias Duśala | 1065–1070 |

| 23 | Vigraha-raja III alias Visala | 1070–1090 |

| 24 | Prithvi-raja I | 1090–1110 |

| 25 | Ajaya-raja II | 1110–1135 |

| 26 | Arno-raja alias Ana | 1135–1150 |

| 27 | Jagad-deva | 1150 |

| 28 | Vigraha-raja IV alias Visaladeva | 1150–1164 |

| 29 | Apara-gangeya

|

1164–1165 |

| 30 | Prithvi-raja II | 1165–1169 |

| 31 | Someshvara | 1169–1178 |

| 32 | Prithviraja III (Rai Pithora)

|

1177–1192 |

| 33 | Govinda-raja IV | 1192 |

| 34 | Hari-raja | 1193–1194 |

References

- ^ Schwartzberg, Joseph E. (1978). A Historical Atlas of South Asia. Oxford University Press, Digital South Asia Library. p. 147, Map "d". Archived from the original on 5 June 2021. Retrieved 25 March 2021.

- ISBN 978-0-415-32919-4.

When Gurjara Pratiharas power declined after the sacking of Kannauj by the Rashtrakutkas in the early tenth century many Rajput princes declared their independence and founded their own kingdoms, some of which grew to importance in the subsequent two centuries. The better known among these dynasties were the Chaulukyas or Solankis of Kathiawar and Gujarat, the Chahamanas (i.e. Chauhan) of eastern Rajasthan (Ajmer and Jodhpur), and the Tomaras who had founded Delhi (Dhillika) in 736 but had then been displaced by the Chauhans in the twelfth century.

- Brajadulal Chattopadhyaya (2006). Studying Early India: Archaeology, Texts and Historical Issues. Anthem. p. 116. ISBN 978-1-84331-132-4.

The period between the seventh and the twelfth century witnessed gradual rise of a number of new royal-lineages in Rajasthan, Gujarat, Madhya Pradesh and Uttar Pradesh, which came to constitute a social-political category known as 'Rajput'. Some of the major lineages were the Pratiharas of Rajasthan, Uttar Pradesh and adjacent areas, the Guhilas and Chahamanas of Rajasthan, the Caulukyas or Solankis of Gujarat and Rajasthan and the Paramaras of Madhya Pradesh and Rajasthan.

- ISBN 978-0-19-564050-2.

This is curious statement for the Chahamanas were known to be one of the pre-eminent Rajput families regarded as..

- ISBN 978-1-4051-9509-6. Archivedfrom the original on 12 July 2023. Retrieved 24 August 2021.

"From the process of migration and metamorphosis of lowly groups into Rajputs new Rajput clans were formed some of these clans The Pratiharas, Guhilas and Chahamanas

- David Ludden (2013). India and South Asia: A Short History. Oneworld Publications. p. 64. ISBN 978-1-78074-108-6.

By contrast in Rajasthan a single warrior group evolved called Rajput (from Rajaputra-sons of kings): they rarely engaged in farming, even to supervise farm labour as farming was literally beneath them, farming was for their peasant subjects. In the ninth century separate clans of Rajputs Cahamanas (Chauhans), Paramaras (Pawars), Guhilas (Sisodias) and Caulukyas were splitting off from sprawling Gurjara Pratihara clans...

- Peter Robb (2011). A History of India. Macmillan International Higher Education. p. 59. ISBN 978-0-230-34549-2.

Muhammad of Ghor was another Afghan Turk invader. He established a much wider control in North India. The Rajputs were unable to resist him, following his defeat of Prithviraja III, king of Chauhans, a Rajput clan based southeast of Delhi

- ISBN 978-81-250-3226-7. Archivedfrom the original on 10 March 2023. Retrieved 14 June 2022.

The rise of a new section called the Rajputs and the controversy about their origins have already been mentioned. With the break-up of the Pratihara empire, a number of Rajput states camne into existence in north India. The most important of these were the Gahadavalas of Kanauj, the Paramaras of Malwa, and the Chauhans of Ajmer

- ISBN 978-0-19-565114-0.

From Ajmer in Rajasthan, the former capital of the defeated Cahamana Rajputs – also, significantly, the wellspring of Chishti piety the post-1192 pattern of temple desecration moved swiftly down the Gangetic Plain as Turkish military forces sought to extirpate local ruling houses in the late twelfth and early thirteenth century

- ISBN 978-0-19-564919-2.

The Tomaras ultimately met their destruction at the hand of another Rajput clan, the Chauhans or Chahamanas. Delhi was captured from the Tomaras by the Chauhan king Vigraharaja IV (the Visala Deva of the traditional bardic histories) in the middle of twelfth century

- Shail Mayaram (2003). Against history, against state : counterperspectives from the margins. New York: Columbia University Press. p. 22. OCLC 52203150.

The Chauhans (Cahamanas) Rajputs had emerged in the later tenth century and established themselves as a paramount power, overthrowing the Tomar Rajputs. In 1151 the Tomar Rajput rulers (and original builders) of Delhi were overthrown by Visal Dev, the Chauhan ruler of Ajmer

- Brajadulal Chattopadhyaya (2006). Studying Early India: Archaeology, Texts and Historical Issues. Anthem. p. 116.

- ^ R. B. Singh 1964, p. 11.

- ^ R. B. Singh 1964, p. 89.

- ^ R. B. Singh 1964, pp. 10–12.

- ^ R. B. Singh 1964, p. 25-26.

- ^ Alf Hiltebeitel 1999, p. 447.

- ^ Har Bilas Sarda 1935, pp. 220–221.

- ISBN 0226742210. Archivedfrom the original on 5 June 2021. Retrieved 25 March 2021.

- ^ a b c Har Bilas Sarda 1935, p. 217.

- ^ Har Bilas Sarda 1935, p. 214.

- ^ a b Cynthia Talbot 2015, p. 33.

- ^ Har Bilas Sarda 1935, p. 223.

- ^ Har Bilas Sarda 1935, p. 224.

- ^ Har Bilas Sarda 1935, p. 225.

- ^ Dasharatha Sharma 1959, p. 23.

- ^ R. B. Singh 1964, p. 100.

- ^ R. B. Singh 1964, p. 103.

- ^ a b Dasharatha Sharma 1959, pp. 34–35.

- ^ R. B. Singh 1964, pp. 131–132.

- ^ Dasharatha Sharma 1959, p. 40.

- ^ R. B. Singh 1964, p. 138-140.

- ^ R. B. Singh 1964, p. 140-141.

- ^ Dasharatha Sharma 1959, p. 60-61.

- ^ R. B. Singh 1964, p. 150.

- ^ Dasharatha Sharma 1959, p. 62.

- ^ R. B. Singh 1964, p. 156.

- ^ Cynthia Talbot 2015, pp. 39.

- ^ Iqtidar Alam Khan 2008, p. xvii.

- ^ R. B. Singh 1964, p. 221.

- ^ Dasharatha Sharma 1959, p. 87.

- ^ Dasharatha Sharma 1959, p. 26.

- ^ R. B. Singh 1964, p. 104.

- ^ R. B. Singh 1964, p. 124.

- ^ R. B. Singh 1964, p. 128.

- ^ a b Dasharatha Sharma 1959, pp. 69–70.

- ^ R. B. Singh 1964, p. 159.

- ^ Cynthia Talbot 2015, pp. 37–38.

- ^ Dasharatha Sharma 1959, p. 38.

- ^ Dasharatha Sharma 1959, p. 41.

- ISBN 0226742210. Archivedfrom the original on 6 February 2022. Retrieved 2 May 2022.

- ^ Anita Sudan 1989, pp. 312–316.

- ^ R. B. Singh 1964, pp. 51–70.

Bibliography

- ISBN 978-0-226-34055-5. Archivedfrom the original on 9 December 2023. Retrieved 18 February 2017.

- Anita Sudan (1989). A study of the Cahamana inscriptions of Rajasthan. Research. OCLC 20754525.

- Cynthia Talbot (2015). The Last Hindu Emperor: Prithviraj Cauhan and the Indian Past, 1200–2000. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781107118560.

- ISBN 9780842606189. Archivedfrom the original on 3 July 2023. Retrieved 5 October 2016.

- Har Bilas Sarda (1935). Speeches And Writings Har Bilas Sarda. Ajmer: Vedic Yantralaya.

- Iqtidar Alam Khan (2008). Historical Dictionary of Medieval India. Scarecrow Press. ISBN 9780810864016. Archivedfrom the original on 3 July 2023. Retrieved 17 June 2016.

- R. B. Singh (1964). History of the Chāhamānas. N. Kishore. from the original on 3 July 2023. Retrieved 17 June 2016.