Zhang Qian

Zhang Qian 張騫 | |

|---|---|

Han Wudi, for his expedition to Central Asia from 138 to 126 BC, Mogao Caves mural, 618 – 712... | |

| Born | 195 BC |

| Died | c. 114 BC |

| Occupation | Explorer |

| Zhang Qian | ||

|---|---|---|

Hanyu Pinyin Zhāng Qiān | | |

| Gwoyeu Romatzyh | Jang Chian | |

| Wade–Giles | Chang1 Ch'ien1 | |

| IPA | [ʈʂáŋ tɕʰjɛ́n] | |

| Yue: Cantonese | ||

| Yale Romanization | Jēung Hīn | |

| Jyutping | Zoeng1 Hin1 | |

| IPA | [tsœːŋ˥ hiːn˥] | |

| Southern Min | ||

| Hokkien POJ | Tiuⁿ Khian | |

| Middle Chinese | ||

| Middle Chinese | ɖjang kʰjen | |

| Old Chinese | ||

| Baxter–Sagart (2014) | *C.traŋ C.qʰra[n] | |

Zhang Qian (

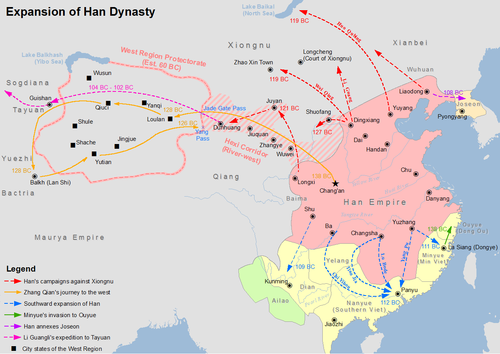

He played an important pioneering role for the future Chinese conquest of lands west of Xinjiang, including swaths of Central Asia and even lands south of the Hindu Kush (see Protectorate of the Western Regions). This trip created the Silk Road that marked the beginning of globalization between the countries in the east and west.[2][3][4][5]

Zhang Qian's travel was commissioned by Emperor Wu with the major goal of initiating transcontinental trade in the Silk Road, as well as create political protectorates by securing allies.[6] His missions opened trade routes between East and West and exposed different products and kingdoms to each other through trade. Zhang's accounts were compiled by Sima Qian in the 1st century BC. The Central Asian parts of the Silk Road routes were expanded around 114 BC largely through the missions of and exploration by Zhang Qian.[7] Today, Zhang is considered a Chinese national hero and revered for the key role he played in opening China and the countries of the known world to the wider opportunity of commercial trade and global alliances.[8] Zhang Qian is depicted in the Wu Shuang Pu (無雙譜, Table of Peerless Heroes) by Jin Guliang.

Zhang Qian's Missions

Zhang Qian was born in Chenggu district just east of Hanzhong in the north-central province of Shaanxi, China.[9] He entered the capital, Chang'an, today's Xi'an, between 140 BC and 134 BC as a Gentleman (郎), serving Emperor Wu of the Han dynasty. At the time the nomadic Xiongnu tribes controlled what is now Inner Mongolia and dominated the Western Regions, Xiyu (西域), the areas neighbouring the territory of the Han dynasty. The Han emperor was interested in establishing commercial ties with distant lands but outside contact was prevented by the hostile Xiongnu.[citation needed]

The Han court dispatched Zhang Qian, a military officer who was familiar with the Xiongnu, to the Western Regions in 138 BC with a group of ninety-nine members to make contact and build an alliance with the Yuezhi against the Xiongnu. He was accompanied by a guide named Ganfu (甘父), a Xiongnu who had been captured in war.[10] The objective of Zhang Qian's first mission was to seek a military alliance with the Yuezhi,[11] in modern Tajikistan. However to get to the territory of the Yuezhi he was forced to pass through land controlled by the Xiongnu who captured him (as well as Ganfu) and enslaved him for thirteen years.[12] During this time he married a Xiongnu wife, who bore him a son, and gained the trust of the Xiongnu leader.[13][14][15]

Zhang and Ganfu (as well as Zhang's Xiongnu wife and son) were eventually able to escape and, passing

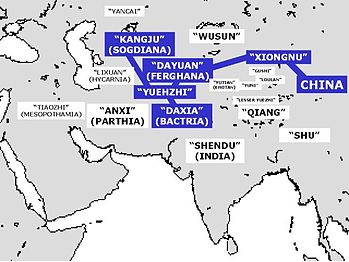

Zhang Qian returned in 125 BC with detailed news for the Emperor, showing that sophisticated civilizations existed to the West, with which China could advantageously develop relations. The Shiji relates that "the Emperor learned of the Dayuan (大宛), Daxia (大夏), Anxi (安息), and the others, all great states rich in unusual products whose people cultivated the land and made their living in much the same way as the Chinese. All these states, he was told, were militarily weak and prized Han goods and wealth".[19] Upon Zhang Qian's return to China he was honoured with a position of palace counsellor.[20] Although he was unable to develop commercial ties between China and these far-off lands, his efforts did eventually result in trade mission to the Wusun people in 119 BC which led to trade between China and Persia.[21]

On his mission Zhang Qian had noticed products from an area now known as

Zhang Qian's reports

The reports of Zhang Qian's travels are quoted extensively in the 1st century BC Chinese historic chronicles "Records of the Great Historian" (

Dayuan (大宛, Ferghana)

After being released from captivity by Xiongnu, Zhang Qian visited Dayuan, located in the Fergana region west of the Tarim Basin. The people of Dayuan were being portrayed as sophisticated urban dwellers similar to the Parthians and the Bactrians. The name Dayuan is thought to be a transliteration of the word Yona, the Greek descendants that occupied the region from the 4th to the 2nd century BCE. It was during this stay that Zhang reported the famous tall and powerful "blood-sweating" Ferghana horse. The refusal by Dayuan to offer these horses to Emperor Wu of Han resulted in two punitive campaigns launched by the Han dynasty to acquire these horses by force.[25]

- "Dayuan lies south-west of the territory of the Xiongnu, some 10,000 Shiji, 123, Zhang Qian quote, trans. Burton Watson).[26]

Later the Han dynasty conquered the region in the War of the Heavenly Horses.[27]

Yuezhi (月氏)

After obtaining the help of the king of Dayuan, Zhang Qian went south-west to the territory of the Yuezhi, with whom he was supposed to obtain a military alliance against the Xiongnu.[28]

- "The Great Yuezhi live some 2,000 or 3,000 li (1,000 or 1,500 kilometres) west of Dayuan, north of the Gui (Shiji, 123, Zhang Qian quote, trans. Burton Watson).

Zhang Qian also describes the origins of the Yuezhi, explaining they came from the eastern part of the Tarim Basin. This has encouraged some historians to connect them to the Caucasoid mummies of the Tarim. (The question of links between the Yuezhi and the Tocharians of the Tarim is still debatable.)[29]

- "The Yuezhi originally lived in the area between the Qilian or Heavenly Mountains (Shiji, 123, Zhang Qian quote, trans. Burton Watson).

A smaller group of Yuezhi, the "Little Yuezhi", were not able to follow the exodus and reportedly found refuge among the "Qiang barbarians".

Zhang was the first Chinese to write about one humped dromedary camels which he saw in this region.[30]

Daxia (大夏, Bactria)

Zhang Qian probably witnessed the last period of the Greco-Bactrian Kingdom, as it was being subjugated by the nomadic Yuezhi. Only small powerless chiefs remained, who were apparently vassals to the Yuezhi horde. Their civilization was urban, almost identical to the civilizations of Anxi and Dayuan, and the population was numerous.

- "Daxia is situated over 2,000 li (1,000 kilometres) south-west of Shiji, 123, Zhang Qian quote, translation Burton Watson).

Cloth from Shu (Sichuan) was found there.[31]

Shendu (身毒, India)

Zhang Qian also reports about the existence of India south-east of Bactria. The name Shendu (身毒) comes from the Sanskrit word "Sindhu", meaning the Indus river. Sindh was at the time ruled by Indo-Greek Kingdoms, which explains the reported cultural similarity between Bactria and India:

- "Southeast of Daxia is the kingdom of Shendu (India)... Shendu, they told me, lies several thousand li south-east of Daxia (Bactria). The people cultivate the land and live much like the people of Daxia. The region is said to be hot and damp. The inhabitants ride elephants when they go in battle. The kingdom is situated on a great river (Shiji, 123, Zhang Qian quote, trans. Burton Watson).

Anxi (安息, Parthia)

Zhang Qian identifies "Anxi" (

- "Anxi is situated several thousand Shiji, 123, Zhang Qian quote, trans. Burton Watson).

Tiaozhi (条支, Seleucid Empire in Mesopotamia)

Zhang Qian's reports on Mesopotamia and the Seleucid Empire, or Tiaozhi (条支), are in tenuous terms. He did not himself visit the region, and was only able to report what others told him.

- "Tiaozhi (Mesopotamia) is situated several thousand li west of Anxi (Shiji, 123, Zhang Qian quote, trans. Burton Watson).

Kangju (康居) northwest of Sogdiana (粟特)

Zhang Qian also visited directly the area of

- "Kangju is situated some 2,000 li (1,000 kilometres) north-west of Dayuan (Bactria). Its people are nomads and resemble the Yuezhi in their customs. They have 80,000 or 90,000 skilled archer fighters. The country is small, and borders Dayuan. It acknowledges sovereignty to the Yuezhi people in the South and the Xiongnu in the East." (Shiji, 123, Zhang Qian quote, trans. Burton Watson).

Yancai (奄蔡, Vast Steppe)

- "Yancai lies some 2,000 Shiji, 123, Zhang Qian quote, trans. Burton Watson).

Development of East-West contacts

Following Zhang Qian's embassy and report, commercial relations between China and Central as well as Western Asia flourished, as many Chinese missions were sent throughout the end of the 2nd century BC and the 1st century BC, initiating the development of the Silk Road:

- "The largest of these embassies to foreign states numbered several hundred persons, while even the smaller parties included over 100 members... In the course of one year anywhere from five to six to over ten parties would be sent out." (Shiji, trans. Burton Watson).[33]

Many objects were soon exchanged, and travelled as far as Guangzhou in the East, as suggested by the discovery of a Persian box and various artefacts from Central Asia in the 122 BC tomb of King Zhao Mo of Nanyue.[34]

Murals in

China also sent a mission to Anxi, which were followed up by reciprocal missions from Parthian envoys around 100 BC:

- "When the Han envoy first visited the kingdom of Arsacidruler) dispatched a party of 20,000 horsemen to meet them on the eastern border of the kingdom... When the Han envoys set out again to return to China, the king of Anxi dispatched envoys of his own to accompany them... The emperor was delighted at this." (adapted from Shiji, 123, trans. Burton Watson).

The Roman historian

- "Even the rest of the nations of the world which were not subject to the imperial sway were sensible of its grandeur, and looked with reverence to the Roman people, the great conqueror of nations. Thus even Scythians and Sarmatians sent envoys to seek the friendship of Rome. Nay, the Seres came likewise, and the Indians who dwelt beneath the vertical sun, bringing presents of precious stones and pearls and elephants, but thinking all of less moment than the vastness of the journey which they had undertaken, and which they said had occupied four years. In truth it needed but to look at their complexion to see that they were people of another world than ours." ("Cathay and the way thither", Henry Yule).

In 97, the Chinese general Ban Chao dispatched an envoy to Rome in the person of Gan Ying.

Several Roman embassies to China followed from 166, and are officially recorded in Chinese historical chronicles.

Final years and legacy

The

"The indications regarding the year of his passing differ, but Shih Chih-mien (1961), p. 268 shows beyond doubt that he died in 113 B.C. His tomb is situated in Chang-chia ts'un 張家村 near Ch'eng-ku . . . ; during repairs carried out in 1945 a clay mold with the inscription 博望家造 [Home of the Bowang (Marquis)] was found, as reported by Ch'en Chih (1959), p. 162." Hulsewé and Loewe (1979), p. 218, note 819.

Other achievements

From his missions he brought back many important products, the most important being alfalfa seeds (for growing horse fodder), strong horses with hard hooves, and knowledge of the extensive existence of new products, peoples and technologies of the outside world. He died c. 114 BC after spending twenty-five years travelling on these dangerous and strategic missions. Although at a time in his life he was regarded with disgrace for being defeated by the Xiongnu, by the time of his passing he had been bestowed with great honours by the emperor.[36][37][38]

Zhang Qian's journeys had promoted a great variety of economic and cultural exchanges between the Han dynasty and the Western Regions. Because silk became the dominant product traded from China, this great trade route later became known as the Silk Road.[39]

See also

Footnotes

- ^ Loewe (2000), p. 688.

- ^ "ZHANG QIAN, EXPLORER CENTRAL ASIA".

- ^ "Zhang Qian — Pioneer of the Silk Road in History of China".

- ^ "The Chinese Explorer Zhang Qian on a Raft".

- ^ Higa, Kiyota (2015-01-01). "Legend of Silk Road pioneer lives on".

- ^ Xia, Zhihou (2018-03-15). "Zhang Qian". Retrieved 2021-03-01.

- ISBN 962-217-721-2.

- ^ "The History and Legacy of the Silk Road route".

- ISBN 962-217-721-2(Paperback).

- ^ Watson (1993), p. 231.

- ^ Silk Road, North China, C. Michael Hogan, The Megalithic Portal, ed. Andy Burnham

- ISBN 978-0-520-23786-5

- ISBN 978-0-231-13924-3. Retrieved 2011-04-17.

- ISBN 978-0-8021-4297-9. Retrieved 2011-04-17.

- ISBN 7-5085-0832-7. Retrieved 2011-04-17.

- ^ Watson (1993), p. 232.

- ^ "Zhang Qian".

- ISBN 0-395-87087-9. Retrieved 2011-04-17.

- ^ Watson (1993), chap. 123.

- ISBN 0-520-23674-2

- ^ Garver, John W. (2006-12-11). "Twenty Centuries of Friendly Cooperation: The Sino-Iranian Relationship".

- ISBN 0-8160-4374-4(pbk).

- ISBN 0-8160-4640-9. Retrieved 2011-04-17.

- ^ "The Expedition of Zhang Qian".

- ^ Indian Society for Prehistoric & Quaternary Studies (1998). Man and environment, Volume 23, Issue 1. Indian Society for Prehistoric and Quaternary Studies. p. 6. Retrieved 2011-04-17.

- ^ "Famous Travelers On The Silk Road".

- ^ Blackwood, Andy (2018-01-04). "The Heavenly Horses of the Han Dynasty". Retrieved 2021-01-02.

- ^ Qian, Sima. "Zhang Qian's Western Expedition" (PDF).

- ^ "Section 13 – The Kingdom of the Da Yuezhi 大月氏 (the Kushans)".

- ^ Chinese Recorder. Presbyterian Mission Press. 1875. pp. 15–.

- ISBN 978-0-7914-6682-7.

- ^ The Kingdom of Anxi

- ^ "Heavenly horses of Ferghana".

- ISBN 978-1-4008-6513-0.

- ^ Watson (1993), p. 240.

- ^ Watson (1993), pp. 231–239, 181, 231–241.

- ISBN 0-8160-4374-4(pbk).

- ^

Alemany, Agustí (2000). Sources on the Alans: A Critical Compilation. BRILL. p. 396. ISBN 9004114424. Retrieved 2008-05-24.

- ^

Asiapac Editorial, Chungjiang Fu, Liping Yang, Chungjiang Fu, Liping Yang (2006). Chinese History: Ancient China to 1911 – Google Book Search. Asiapace Books. p. 84. ISBN 9789812294395. Retrieved 2008-05-24.)

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link

References

- Hulsewé, A. F. P. and Loewe, M. A. N., (1979). China in Central Asia: The Early Stage 125 BC – AD 23: an annotated translation of chapters 61 and 96 of the History of the Former Han Dynasty. Leiden: E. J. Brill.

- Loewe, Michael (2000). "Zhang Qian 張騫". A Biographical Dictionary of the Qin, Former Han, and Xin Periods (220 BC – AD 24). Leiden: Brill. pp. 687–9. ISBN 90-04-10364-3.

- Fairbank, John K.(eds.). The Cambridge History of China, Volume 1: The Ch'in and Han Empires, 221 B.C. – A.D. 220. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 377–462.

Further reading

- Yap, Joseph P, (2019). The Western Regions, Xiongnu and Han, from the Shiji, Hanshu and Hou Hanshu. ISBN 978-1792829154