Charles Frohman

Charles Frohman | |

|---|---|

Frohman in 1914 | |

| Born | July 15, 1856 Sandusky, Ohio, U.S. |

| Died | May 7, 1915 (aged 58) |

| Occupation(s) | Theatre manager and producer |

| Relatives | Daniel Frohman (brother) Gustave Frohman (brother) Philip H. Frohman (nephew) |

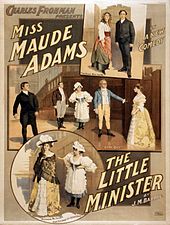

Charles Frohman (July 15, 1856 – May 7, 1915) was an American theater manager and producer, who discovered and promoted many stars of the American stage. Frohman produced over 700 shows, and among his biggest hits was

In 1896, Frohman co-founded the

At the height of his fame, Frohman died in the 1915 sinking of the RMS Lusitania.

Life and career

Charles Frohman was born to a

Frohman's first success as a producer was with

Frohman was known for his ability to develop talent. His stars included

In 1897, Frohman leased the

Other Frohman hits included

Death on the RMS Lusitania

Frohman made his annual trip to Europe in May 1915 to oversee his London and Paris "play markets", sailing on the Cunard Line's RMS Lusitania. Songwriter Jerome Kern was meant to accompany him on the voyage, but overslept after being kept up late playing requests at a party.[7] William Gillette was also to have accompanied him, but was forced to fulfill a contracted appearance in Philadelphia.[8]

Frohman's rheumatic knee, from a fall three years earlier, had been ailing for most of the voyage, but he was feeling better on the morning of May 7, a bright, sunny day. He entertained guests in his suite and later at his table. He was regaling them with tales of his life in the theater when, at 2:10 in the afternoon, within fourteen miles of the Old Head of Kinsale, with the coast of Ireland in sight, a torpedo from the German U-boat U-20 struck the Lusitania on the starboard side. Within a minute, there was a second explosion, followed by several smaller ones.[9]

As passengers began to panic, Frohman stood on the promenade deck, chatting with friends and smoking a cigar. He calmly remarked, "This is going to be a close call."[10] Frohman, with a disabled leg and walking with a cane, could not have jumped from the deck into a lifeboat, so he was trapped. Instead, he and millionaire Alfred Vanderbilt tied lifejackets to "Moses baskets" containing infants who had been asleep in the nursery when the torpedo struck. Frohman then went out onto the deck, where he was joined by actress Rita Jolivet, her brother-in-law George Vernon and Captain Alick Scott. In the final moments, they clasped hands and Frohman paraphrased his greatest hit, Peter Pan: "Why fear death? It is the most beautiful adventure that life gives us." Jolivet, the only survivor of Frohman's party, was standing with Frohman as the ship sank. She later said, "with a tremendous roar a great wave swept along the deck. We were all divided in a moment, and I have not seen any of those brave men alive since."[11]

At his death, Frohman was 58. His body later washed ashore below the Old Head of Kinsale, and lay among 147 others awaiting identification, where a rescued American identified him from newspaper photographs. His body, alone among all the others, was not disfigured. It was determined that he was killed by a heavy object falling on him, rather than by drowning.

A memorial to Frohman is located on The Causeway at Marlow on Thames. The memorial, by the artist Leonard Stanford Merrifield, features a drinking fountain with a sculptured nymph and inscription.[15][16]

Portrayals in films, television and stage

Frohman was portrayed by

Notes

- ^ Klawans, Stuart. "Finding an Audience: Years of Invisibility", The Forward, April 9, 2004, accessed December 19, 2015

- ^ Certified Birth Certificate, Sandusky, Ohio; and the 1860 Federal Census for Sandusky, Ohio, which shows: "Charley", age 4

- ^ Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1922). . Encyclopædia Britannica (12th ed.). London & New York: The Encyclopædia Britannica Company.

- ^ a b c d Kenrick, John. "Who's Who in Musicals: Additional Bios XI". Musicals101.com, 2004, accessed May 17, 2010

- ^ Marcosson and Frohman (1916) [page needed]

- ^ Zecher, p. 169.

- ^ Denison, pp. 21–22; and McLean, p. 98

- ^ Zecher, p. 442; Philadelphia Inquirer, "The Call Boy's Chat," February 7, 1930, Theatres, Music, Radio, Radio Programs Section, p. TH1.

- Diana Prestonattributed it to exploding steam lines. See Preston, Diana, Lusitania, An Epic Tragedy (Walker & Company, 2002), p. 453.

- ^ Frohman and Marcosson, p. 386; Preston, p. 204; "Frohman, Charles". The Lusitania Resource; Zecher, p. 462.

- ^ Ellis, Frederick D. The Tragedy of the Lusitania (National Publishing Company, 1915), pp. 38–39; Preston, p. 204; "Frohman Calm; Not Concerned About Death, Welcomed It as Beautiful Adventure, He Told Friends at End," New York Tribune, May 11, 1915, p. 3; Frohman and Marcosson, p. 387; Frohman, Charles. The Lusitania Resource"

- ^ Frohman and Marcosson, p. 387; Survivor discovering Frohman's body quoted in Hoehling, Adolph A., The Last Voyage of the Lusitania (Random House Value Publishing, 1991), pp. 217–18; Ramsey, David, Lusitania, Saga and Myth (W. W. Norton & Company, 2001), pp. 96–97; New York American, May 9, 1915, p. 1; New York Press, "Finds Frohman's Body", May 9, 1915, p. 5; "Charles Frohman". The Lusitania Resource; Zecher, p. 443.

- ^ New York Tribune, "Frohman Burial Plans, Two Funeral Services May 25; 8 Pallbearers Named," May 14, 1915, p. 5; pallbearers -- primary and honorary -- included Otis Skinner, William Gillette, Henry Miller, E. H. Sothern, William Faversham, John Barrymore, Augustus Thomas, Edward Sheldon, Henry Arthur Jones, Paul M. Potter, George Ade and Harry Leon Wilson. See Zecher, p. 443, 676.

- ^ Frohman and Marcosson, pp. 389-90

- ^ Eliot, Jane. "The Nymph That Mourns a Famous American" Archived 2011-08-27 at the Wayback Machine. Straightforward article showcase, accessed August 7, 2011

- ^ "War Memorials Register: C Frohman". Imperial War Museum. Retrieved 2 February 2021.

- ^ Bradley, Matthew R. "Richard Matheson – Storyteller: Signs o' the Time", Tor.com, December 21, 2010, accessed January 14, 2015

References

- Denison, Chuck, and Duncan Schiedt. The Great American Songbook. Bandon, Oregon, Robert D. Reed Publishers, 2004. ISBN 978-1-931741-42-2.

- Marcosson, Isaac Frederick; Frohman, Daniel (1916). Charles Frohman: Manager and Man. John Lane, The Bodley Head.

- McLean, Lorraine Arnal. Dorothy Donnelly. Jefferson, North Carolina, McFarlan, 1999. ISBN 978-0-7864-0677-7.

- Preston, Diana. Lusitania, An Epic Tragedy (Walker & Company, 2002).

- Skinner, Otis. Footlights and Spotlights (Blue Ribbon Books, 1924).

- Zecher, Henry. William Gillette, America's Sherlock Holmes (Xlibris Corporation, 2011).

Further reading

- Anderson, John. The American Theatre (The Dial Press, 1938).

- Atkinson, Brooks. Broadway (The MacMillan Company, 1970).

- Bailey, Thomas A. & Paul B. Ryan. The Lusitania Disaster (The Free Press, 1975).

- Binns, Archie. Mrs. Fiske and the American Theatre (Crown Publishers, Inc., 1955).

- Bordman, Gerald. The Concise Oxford Companion to American Theatre (Oxford University Press, 1984).

- Burke, Billie. With a Feather on My Nose (Appleton-Century-Crofts, Inc., 1949).

- Churchill, Allen. The Great White Way (E. P. Dutton & Co., Inc., 1962).

- Frohman, Daniel. Daniel Frohman Presents, An Autobiography (Claude Kendall & Willoughby Sharp, 1935).

- Frohman, Daniel. Encore (Lee Furman, Inc., 1937).

- Hughes, Glenn. A History of the American Theatre 1700-1950 (Samuel French, 1951).

- Marker, Lise-Lone. David Belasco: Naturalism in the American Theatre (Princeton University Press, 1974).

- Morehouse, Ward. Matinee Tomorrow, Fifty Years of Our Theater (Whittlesey House, 1949).

- Robbins, Phyllis. The Young Maude Adams (Marshall Johns Company, 1959).

- Stagg, Jerry. The Brothers Shubert (Random House, 1968).

- Timberlake, Craig. The Bishop of Broadway (Library Publishers, 1954).

External links

- Works by or about Charles Frohman at Internet Archive

- Charles Frohman at the Internet Broadway Database

- Biography of Frohman at The Lusitania Resource

- Profile of Frohman

- Production and cast lists for a number of London shows produced by Frohman

- Includes an anecdote about Frohman's last words and deeds on the Lusitania

- Frohman and Edna May

- Site dedicated to Charles Frohman