Charles Santley

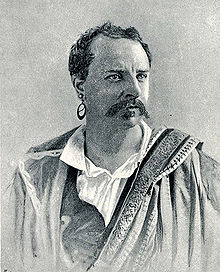

![Photograph of Charles Santley, [ca. 1859–1870]. Carte de Visite Collection, Boston Public Library.](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/1/10/Charles_Santley_-_DPLA_-_7f394a3ebe68ee176453a91ff818b337_%28page_1%29.jpg/220px-Charles_Santley_-_DPLA_-_7f394a3ebe68ee176453a91ff818b337_%28page_1%29.jpg)

Sir Charles Santley (28 February 1834 – 22 September 1922) was an English opera and oratorio singer with a bravura[Note 1] technique who became the most eminent English baritone and male concert singer of the Victorian era. His has been called 'the longest, most distinguished and most versatile vocal career which history records.'[1]

Santley appeared in many major opera and oratorio productions in Great Britain and North America, giving numerous recitals as well. Having made his debut in Italy in 1857 after undertaking vocal studies in that country, he elected to base himself in England for the remainder of his life, apart from occasional trips overseas. One of the highlights of his stage career occurred in 1870 when he led the cast in the first

Santley also wrote books on vocal technique and two sets of memoirs.

Early training

Santley was the elder son of William Santley, a journeyman bookbinder,[2] organist and music teacher of Liverpool in northern England.[3] He had a brother and two sisters, one of whom named Catherine should not be confused with the actor-manager Kate Santley.[4] He was educated at the Liverpool Institute High School, and as a boy sang alto in the choir of a local Unitarian church.[5] His voice began to break before he was fourteen. Following musical lessons from his father (who insisted upon his singing tenor[6]), he passed the examination for admission to the second tenors of the Liverpool Philharmonic Society on his fifteenth birthday, and in the same year took part in the concerts at the opening of the Philharmonic Hall.[5]

It was not until he reached the age of seventeen to eighteen that he rebelled against his father's decree and dropped into the bass clef, and was pronounced to be a bass.

In 1855, Santley went to Italy to study as a singer, with advice from Sims Reeves to visit

He made his stage debut on 1 January 1857 in

Oratorio, 1857–1872

In 1857 Santley returned to London, and made his first appearance (16 November) for

After an audition with

In 1861 he sang Elijah in his first appearance at the

The year 1863 saw his first appearance at the

The autumn of 1865 witnessed his debut appearance at the Gloucester Festival, where he sang Elijah, the first part of St. Paul, part of Messiah, and Mendelssohn's First Walpurgis Night. In 1866 he was at Worcester Festival, and then at Norwich, where Costa's Naaman was given again, in the presence of the Prince and Princess of Wales, and Benedict's new cantata St Cecilia (libretto by Chorley) was introduced. At Hereford in 1867 the main event for Santley was singing with the famous soprano Jenny Lind for the first time, in the oratorio Ruth by Otto Goldschmidt. There, and at Birmingham festival, Willoughby Weiss took most of the sacred bass or baritone roles. Santley sang bass arias from the Messiah, Gounod's Mass, Benedict's St Cecilia and J. F. Barnett's The Ancient Mariner.[2]

Returning to the Birmingham Festival in 1867 he was a soloist in the premiere of the Sacred Cantata The Woman of Samaria by William Sterndale Bennett, conducted by the composer.

At the Handel Festival in June 1868 he sang the Messiah solos, and on the selection day, 'O voi dell'Erebo' from La Resurrezione and 'O ruddier than the cherry' from

At the close of the 1868–69 season of the

In early 1870, as his departure from the theatre was approaching, Santley sang at concerts in London and at Exeter Hall. Then, under the management of George Wood, he made a six-week concert tour of the provinces. The touring company included Clarice Sinico, the violinist August Wilhelmj and the pianist Arabella Goddard (later joined by Ernst Pauer). Santley's concert singing reached a high point of acclaim during his subsequent United States and Canadian tour of 1871–72. In such songs as "To Anthea", "Simon the Cellarer" and the "Maid of Athens", he was viewed as being unapproachable, and his oratorio singing was praised for perpetuating the finest traditions of the art form.[11] In 1872, he took part in a joint recital with Pauline Rita at St James's Hall, London.[15]

Operatic career 1857–1876

The early years

In the first years after his return to England, Santley used often to sing buffo duets (for example 'Che l'antipatica vostra figura' from Ricci's Chiara di Rosemberg) with

Santley appeared in English opera for

For the season of 1861–62, Santley returned to Covent Garden, opening in

Mapleson's Italian Opera

Mapleson won Santley back for his own Italian opera company, and in the 1862–63 season at Majesty's, he performed in Il trovatore (as Di Luna), The Marriage of Figaro (as Almaviva) and Les Huguenots (as de Nevers). He returned to Covent Garden for the English Opera, however, appearing in the Lily of Killarney, Dinorah, and Balfe's The Armourer of Nantes. In defence of his decision to move to Italian opera, Santley notes that since 1859-60 he had been singing about 110 opera performances per season, in addition to fulfilling concurrent concert engagements.[2]

With Mapleson's Italian Opera he joined some of the 19th century's most celebrated singers, including

The first performance of Faust in England followed. It was given in a problematic English translation by

After hearing Santley's Valentine, Gounod composed the aria Even bravest heart expressly for him to an original English text by Chorley (now, ironically, better known in French translation as Avant de quitter or in Italian as Dio possente) and this was introduced in London in January 1864 at the opening of the spring session. Also appearing in this production were Reeves, Lemmens-Sherrington and

The company in transition

After the festival season, Santley toured in Mapleson's company during the autumn (with Italo Gardoni as lead tenor), appearing in Faust, Oberon and Mireille, In November 1864 he set off for

In the spring of 1865, Giuglini left the company, and the Croatian diva

The year 1867 brought the engagement of Sweden's

After the fire

The company presented a fresh season, commencing in March 1868 at Drury Lane. In it, Santley sang Fernando in

In July Santley appeared in Le Nozze at the Crystal Palace. The London autumn season was held at Covent Garden, with Santley's old hero Karl Formes joining the tour cast. The American soprano Minnie Hauk also appeared (in La Sonnambula). During the ensuing tour, Santley sang Tom Tug in Charles Dibdin's The Waterman for the first time, at Leeds. The next season, he sang it twice more in Leeds, and once each in Sheffield and Bradford. The airs from The Waterman 'The jolly young waterman' and 'Then farewell, my trim-built wherry' were sung by Santley to acclaim.[2]

Her Majesty's remained closed, and in 1869 Mapleson was drawn into a merger with the Royal Italian Opera. With the merged company, Santley performed in Rigoletto with Vanzini,

Early in 1870 the company made an operatic tour of

Attempt to found an English lyric theatre

Rather than accept another season with the joint company, Santley decided to establish a new English Opera enterprise at the

With Carl Rosa's company

The concert tour itself was not a financial success. Santley therefore entered into an agreement with

In 1873 Carl Rosa invited Santley to appear as Telramund in a planned English Lohengrin at Drury Lane. Santley accepted, but the project failed with the untimely death of Mme Parepa-Rosa. (Lohengrin was not heard in London until 1875).[24] Santley's wish to play Wolfram in Tannhäuser also remained unrealised. He disliked the prominence of the Wagnerian orchestra and regretted the innovation which saw orchestral players being relegated to a pit beneath the opera stage.[2]

However, in 1875 Carl Rosa tempted him back to the stage for a season at the Princess's Theatre, London, in which he played in Le nozze di Figaro, Il trovatore, The Siege of Rochelle (as Michel), Cherubini's The Water Carrier (Mikelì) and The Porter of Havre (Martin). In Figaro he was cast as Almaviva, but was transferred to the role of Figaro, singing with Sig. Campobello[25] (Almaviva), Aynsley Cook (Bartolo), Charles Lyall (Basilio), Ostava Torriani (Contessa), Rose Hersee (Susanna), Josephine York (Cherubino) and Mrs Aynsley Cook (Marcellina). This received a special performance for the Prince and Princess of Wales. There was a provincial tour in the autumn.[2]

In autumn 1876 at the Lyceum Theatre, again with Carl Rosa, Santley revived his Flying Dutchman, this time in English, with Ostava Torriani as Senta. Between the London season and the provincial tour which followed they performed it 50 times. Among the cities visited were Edinburgh (four performances) and Glasgow (two performances).[26]

In the same season they undertook a work new to him, Nicolo's

Later years

Santley gave recitals at the

He settled down to concert and oratorio work in England.Santley, to whom European travel had been a holiday routine for many years, toured in Australia and New Zealand in 1889–1890, to the United States and Canada in 1891 and South Africa in 1893 and again in 1903. He sang last at the Birmingham festival in 1891 after an unbroken series of thirty years of appearances there. George Bernard Shaw, describing Santley as the hero of the 1894 Handel Festival, remarked especially on his Honour and Arms and Nasce al Bosco. 'Santley's singing of the division of Selection Day was, humanly speaking, perfect. It tested the middle of his voice from C to C exhaustively; and that octave came out of the test hall-marked; there was not a scrape on its fine surface, not a break or a weak link in the chain anywhere; while the vocal touch was impeccably light and steady, and the florid execution accurate as clockwork.' In these two arias his entire compass from low G to top E flat, and in Nasce al Bosco the top E natural and F, were exhibited 'in such a way as made it impossible for him to conceal any blemish, if there had been one.'[29]

In January 1894 he was with Clara Butt, Edward Lloyd, Antoinette Sterling and other singers at the first of the Chappell's Ballad Concerts, when they were transferred from St James's Hall to Queen's Hall.[30] From 1894 Santley devoted his time increasingly to teaching: between 1903 and 1907 he trained the Australian baritone Peter Dawson, taking him meticulously through Messiah, The Creation and Elijah.[31] Indeed, in 1904 he brought Dawson in on a tour of the West Country, beginning at Plymouth, led by Emma Albani, with William Green (tenor), Giulia Ravogli, Johannes Wolf, Adela Verne and Theodore Flint.[32]

In January 1907 he sang Elijah at

Vocal character

In addition to a 'haunting' beauty of timbre,

Personal life

Santley married twice, first (in 1858) to Gertrude Kemble (granddaughter of Charles Kemble), who before her marriage had a professional career as a soprano singer. Their daughter Edith also became a concert singer. Gertrude died in 1882. The couple had five children.[42]

Santley's second marriage, on 7 January 1884,[43] was to Elizabeth Mary Rose-Innes (Isabel María Rose-Innes Vives), eldest daughter of George (Jorge) Rose-Innes, a Valparaíso merchant and banker whose father was British. They had one son.[44]

Santley converted to

Recordings

Charles Santley made a few recordings, mostly of ballads. His earlier series was made for the

- 2-2862 Simon the Cellarer (Hatton) (10")

- 2-2863 The vicar of Bray (10")

- 052000 Ehi capitano/Non piu andrai (Figaro – Mozart) (12")[47]

- 2-2864 To Anthea (Hatton) (10")

- 02015 Thou'rt passing hence, my brother (Sullivan) (12")

Several years later he cut a group of ballad titles for the Columbia label. Hatton's 'To Anthea' and 'Simon the Cellarer' are characteristic of Santley's earlier ballad repertoire, and are repeated in the Columbia series, which also includes Ethelbert Nevin's 'My Rosary', C.V. Stanford's 'Father O'Flynn,' Sullivan's 'Thou'rt passing hence, my brother,' and other titles.[48]

Books

Santley's publications include the following:

- Method of Instruction for a Baritone Voice, a translation of "Metodo pratico di vocalizzazione, per le voci de basso e baritono" by G. Nava (London, c 1872)

- Student and Singer, Reminiscences of Charles Santley (Macmillan, London 1893)

- The Singing Master (1900)

- The Art of Singing and Vocal Declamation (1908)

- Reminiscences of my Life (Isaac Pitman, London 1909)

Of the volumes of reminiscences, Student and Singer deals with his career up to circa 1870, and Reminiscences of My Life includes material for the later period.

Compositions

- Mass in A flat

- Ave Maria, Berceuse for Orchestra

Santley also composed a number of songs under the pseudonym of Ralph Betterton.[49]

Notes

- ^ From the Italian verb bravare, to show off. A florid, ostentatious style or a passage of music requiring technical skill

References

- ^ Arthur Eaglefield-Hull, A Dictionary of Modern Music and Musicians (Dent, London 1924), 435.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab C. Santley, Student and Singer: The Reminiscences of Charles Santley 3rd Edition (Edward Arnold, London 1892), p.6.

- ^ Eaglefield-Hull 1924: Rosenthal & Warrack, Concise Oxford Dictionary of Opera.

- ^ 1851 and subsequent Census returns for 20 Hardwick Street, West Derby, Liverpool (National Archives HO 107.2192).

- ^ a b John Warrack, "Santley, Sir Charles (1834–1922)", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004, accessed 28 April 2011 (subscription required)

- ^ C. Santley, 'The Art if Singing' (1908), p. 16.

- ^ C. Santley, 'The Art of Singing' (1908), p. 16.

- ^ Rosenthal & Warrack 1974.

- ^ H.J. Wood, My Life of Music (London: Victor Gollancz Ltd, 1946 edition), p. 17.

- ^ William Ludwig's conception of Elijah was considered nobler by some, see Henry Wood, My Life of Music, p. 17.

- ^ a b c d Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 24 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 194.

- ^ R. Elkin, Royal Philharmonic (Ryder, London 1946), p. 62.

- ^ S. Reeves, The Life of Sims Reeves, Written by Himself (Simpkin, Marshall, London 1888), p. 217-218.

- ^ R. Elkin, Royal Philharmonic (Rider, London 1946), 65-71.

- ^ Daily News, 22 May 1872, p. 3

- ^ C. Santley, 'The Art of Singing and Vocal Declamation' (Macmillan and Co., London 1908), pp. 15-17.

- ^ Santley, 'The Art of Singing' (1908), pp. 17-18.

- ^ Santley 1892, 171–72: J. H. Mapleson, The Mapleson Memoirs (Belford, Clarke & Co, Chicago & New York 1888), I, 28.

- ^ Santley, 'The Art of Singing' (1908), p. 18.

- ^ 'di' Murska in Rosethal and Warrack, and in Santley 1892, 'de' Murska in Mapleson 1888.

- ^ Illustrated London News, 3 March 1866, p. 215.

- ^ Mrs Van Zandt, mother of the Mlle. van Zandt who sang at the Opéra-Comique.

- ^ 'Adolph Neuendorff dead', The New York Times 5 December 1897

- ^ Rosenthal and Warrack 1974.

- ^ Signor Campobello was the stage name of Henry McLean Martin, baritone. According to Groves' Dictionary 1890 edition, in 1874 he married the soprano Clarice Sinico, née Marini, afterwards known as Mme Sinico-Campobello.

- ^ Design, Site Buddha Web. "Charles Santley – Opera Scotland".

- ^ a b Eaglefield-Hull 1924, 435.

- ^ Eaglefield-Hull 1924.

- ^ G. B. Shaw, Music in London 1890-94 (Constable, London 1932), III, 254-257.

- ^ R. Elkin, Queen's Hall 1893-1944 (Rider, London 1944), 91.

- ^ P. Dawson, Fifty Years of Song (Hutchinson, London 1951), 17-20.

- ^ Dawson 1951, 25-26.

- ^ a b c Santley 1909

- ^ Herman Klein, Thirty Years of Music in London 1870-1900 (Century Co., New York 1903), 466.

- Hanslick and John McCormack.

- ^ Klein 1903, 49, & n.

- ISBN 0-252-06557-3), p. 25.

- ^ H. J. Wood, My Life of Music (Gollancz, London 1946 (Cheap edition)), p. 91.

- ^ G. Davidson, Opera Biographies (Werner Laurie, London 1955), 267.

- ^ G. B. Shaw, Music in London, 1890-94 (Constable, London 1932), II, 195.

- ^ Shaw 1932, II, 196.

- ^ "Kemble Genealogy Page". Archived from the original on 20 March 2023. Retrieved 29 February 2008.

- ^ "Marriage: Santley–Rose-Innes". The Tablet. 63 (2283). London: 92. 19 January 1884.

- ^

- White, Maude Valerie (1914). Friends and memories. London: Edward Arnold. pp. 75, 236.

- Coo Lyon, José Luis (1971). "Familias extranjeras en Valparaíso en el siglo XIX". Revista de estudios históricos (in Spanish) (17). Instituto Chileno de Investigaciones Genealógicas: 33.

- ^ Bennett 1955,: Bennett 1967.

- ^ Reproduced and discussed in M. Scott, The Record of Singing, Vol. I (Duckworth, London 1977).

- ^ This title in Bennett 1967.

- ^ Scott 1977, 52-53.

- ^ "AIM25 collection description".

Bibliography

- J.R. Bennett, Voices of the Past – Catalogue of Vocal recordings from the English Catalogues of the Gramophone Company, etc. (c1955).

- J.R. Bennett, Voices of the Past – Vol 2. A Catalogue of Vocal recordings from the Italian Catalogues of The Gramophone Company, etc. (Oakwood Press (1957), 1967).

- G. Davidson, Opera Biographies (Werner Laurie, London 1955), 264–267.

- J.H. Mapleson, The Mapleson Memoirs (Chicago & New York 1888).

- S.Reeves, Sims Reeves, His Life and Recollections Written by Himself (Simpkin Marshall & Co, London 1888).

- H. Rosenthal and J. Warrack, Concise Oxford Dictionary of Opera (Corrected Edition, Oxford 1974).

- M. Scott, The Record of Singing to 1914 (Duckworth 1977).

- G.B. Shaw, 1932, Music in London 1890-94 by Bernard Shaw, 3 Vols (Constable & Co, London)

- Herbert Thompson, Herbert. "Sir Charles Santley 1834-1922", The Musical Times, Vol. 63, No. 957 (1 November 1922), pp. 784–92