Chinese Filipino

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these template messages)

|

咱儂 / 咱人 / 華菲人 Chinoy / Tsinoy / Lannang Chinito ( Chinese Malaysians, Han Taiwanese, Thai Chinese , etc. |

|---|

| Chinese Filipino | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Chinese | 咱儂 | |||||

| Simplified Chinese | 咱人 | |||||

| Hokkien POJ | Lán-nâng / Nán-nâng / Lán-lâng | |||||

| ||||||

| Chinese Filipino | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Hanyu Pinyin | Huáfēirén | |||||

| ||||||

Chinese Filipinos[a] (sometimes referred as Filipino Chinese in the Philippines) are Filipinos of Chinese descent with ancestry mainly from Fujian province,[4] but are typically born and raised in the Philippines.[4] Chinese Filipinos are one of the largest overseas Chinese communities in Southeast Asia.[5]

Chinese

Chinese Filipinos are a well established middle class ethnic group and are well represented in all levels of Filipino society.

Identity

The organization Kaisa para sa Kaunlaran (Unity for Progress) omits the hyphen for the term Chinese Filipino, as the term is a noun. The Chicago Manual of Style and the APA, among others, also omits the hyphen. When used as an adjective as a whole, it may take on a hyphenated form or may remain unchanged.[18][19][20]

There are various universally accepted terms used in the Philippines to refer to Chinese Filipinos:[citation needed]

- Philippine Hokkien simplified Chinese: 咱人; traditional Chinese: 咱儂; Pe̍h-ōe-jī: Lán-nâng / Lán-lâng / Nán-nâng, Mandarin simplified Chinese: 华人; traditional Chinese: 華人; pinyin: Huárén)—generalized term referring to any and all Chinese people in or outside the Philippines in general regardless of nationality or place of birth.

- Chinese Filipino, Filipino Chinese or Philippine Chinese (Philippine Hokkien simplified Chinese: 咱人; traditional Chinese: 咱儂; Pe̍h-ōe-jī: Lán-nâng / Lán-lâng / Nán-nâng, Mandarin simplified Chinese: 华菲 / 菲律宾华人 / 菲律宾华侨; traditional Chinese: 華菲 / 菲律賓華人 / 菲律賓華僑; pinyin: Huáfēi / Fēilǜbīn huárén / Fēilǜbīn huáqiáo)—refers to people with some level of Han Chinese ethnicity with Philippine nationality and to people of Han Chinese ethnicity with Chinese nationality (either PRC or ROC) or whichever nationality but were born or mainly raised in the Philippines and usually have permanent residency. This also includes Chinese Filipinos who now live and/or were born overseas, but still have close ties to the community in the Philippines.

- Hokkienese / Fukienese / Fujianese / Fookienese (Philippine Hokkien as a heritage language, though just as any Chinese Filipino may also normally speak Philippine English, Filipino/Tagalog or other Philippine languages (such as Visayan languages) and may also code-switch any and all of these languages, such as Taglish, Bislish, Hokaglish, etc.

- Cantonese (Philippine Hokkien simplified Chinese: 广东人 / 乡亲; traditional Chinese: 廣東儂 / 鄉親; Pe̍h-ōe-jī: Kńg-tang-lâng / Hiong-chhin, Mandarin simplified Chinese: 广东人; traditional Chinese: 廣東人; pinyin: Guǎngdōngrén)—terms referring to Chinese Filipinos whose ancestry is from Guangdong Province in China, especially the Taishanese or Cantonese-speaking regions.

- Hokkienese / Fukienese / Fujianese / Fookienese (

- Philippine Hokkien Chinese: 出世仔 / 出世; Pe̍h-ōe-jī: Chhut-sì-á / Chhut-sì, Mandarin simplified Chinese: 华菲混血; traditional Chinese: 華菲混血; pinyin: Huáfēi hùnxiě)—refers to people who are of mixed Han Chinese and indigenous Filipino ancestry, a common and historical phenomenon in the Philippines especially families tracing from the Spanish colonial times. Those with 75% Han Chineseancestry or more are typically not considered to be characteristically mestizo. Many Chinese mestizos are still Chinese Filipinos, though some with more indigenous Filipino ancestry or family or have just had a very long family history of living and assimilating to life in the Philippines may no longer identify as Chinese Filipino.

- Mainland Chinese, Mainlander (Philippine Hokkien simplified Chinese: 大陆仔 / 中国人 / 唐山人; traditional Chinese: 大陸仔 / 中國儂 / 唐山儂; Pe̍h-ōe-jī: Tāi-dio̍k-á / Tiong-kok-lâng / Tn̂g-soaⁿ-lâng, Mandarin simplified Chinese: 中国人; traditional Chinese: 中國人; pinyin: Zhōngguórén)—refers to any PRC citizens from China (PRC), especially those of Han Chinese ethnicity with Chinese nationality that were raised in China (PRC).

- Taiwanese (Philippine Hokkien simplified Chinese: 台湾人 / 台湾仔; traditional Chinese: 台灣儂 / 臺灣儂 / 台灣仔 / 臺灣仔; Pe̍h-ōe-jī: Tâi-oân-lâng / Tâi-oân-á, Taiwanese Mandarin simplified Chinese: 台湾人; traditional Chinese: 臺灣人 / 台灣人; Hanyu Pinyin: Táiwānrén; Tongyong Pinyin: Táiwanrén; Wade–Giles: Tʽai2-wan1-jen2; Zhuyin Fuhao: ㄊㄞˊ ㄨㄢ ㄖㄣˊ)—refers to ROC citizens from Taiwan (ROC), especially those of Han Chinese ethnicity with Republic of China (Taiwan) nationality that were raised in Taiwan (ROC).

- Hongkonger (Hong Kong (SAR) residency or Hong Kong British National (Overseas) status that were born or raised in Hong Kong (SAR) or British Hong Kong.

- Macanese (Philippine Hokkien simplified Chinese: 澳门人 / 澳门仔; traditional Chinese: 澳門儂 / 澳門仔; Pe̍h-ōe-jī: Ò-mn̂g-lâng / Ò-mn̂g-á, Mandarin simplified Chinese: 澳门人; traditional Chinese: 澳門人; pinyin: Àoménrén, Cantonese Chinese: 澳門人; Cantonese Yale: Ou mùhn yàhn)—refers to people from Macau, especially those of Han Chinese ethnicity with Macau permanent residency that were born or raised in Macau (SAR) or Portuguese Macau.

- .

- Sangley—obsolete term referring to people of unmixed Chinese ancestry, especially fresh first generation Chinese migrants, during the Spanish Colonial Period of the Philippines. The mixed equivalents were likewise the above terms, mestizo de Sangley and tornatrás.

Other terms being used with reference to China include:

- 華人 – Hoâ-jîn or Huárén—a generic term for referring to Chinese people, without implication as to nationality

- 華僑 – Hoâ-kiâo or Huáqiáo—Overseas Chinese, usually China-born Chinese who have emigrated elsewhere

- 華裔 – Hoâ-è or Huáyì—People of Chinese ancestry who were born in, residents of and citizens of another country

"Indigenous Filipino" or simply "Filipino", is used in this article to refer to the Austronesian inhabitants prior to the Spanish Conquest of the islands. During the Spanish Colonial Period, the term indio was used.[citation needed]

However, intermarriages occurred mostly during the Spanish colonial period because Chinese immigrants to the Philippines up to the 19th century were predominantly male.[citation needed] It was only in the 20th century that Chinese women and children came in comparable numbers.[citation needed] Today, Chinese Filipino male and female populations are practically equal in numbers. Chinese mestizos, as a result from intermarriages during the Spanish colonial period, then often opted to marry other Chinese or Chinese mestizos.[citation needed] Generally, Chinese mestizos is a term referring to people with one Chinese parent.

By this definition, the ethnically Chinese Filipino comprise 1.8% (1.35 million) of the population.[21] This figure however does not include the Chinese mestizos who since Spanish times have formed a part of the middle class in Philippine society[citation needed] nor does it include Chinese immigrants from the People's Republic of China since 1949.

History

Early interactions

Ethnic Han Chinese sailed around the Philippine Islands from the 9th century onward and frequently interacted with the local Austronesian people.[22] Chinese and Austronesian interactions initially commenced as bartering and items.[23] This is evidenced by a collection of Chinese artifacts found throughout Philippine waters, dating back to the 10th century.[23] Since Song dynasty times in China and precolonial times in the Philippines, evidence of trade contact can already be observed in the Chinese ceramics found in archaeological sites, like in Santa Ana, Manila.[23]

- Chinese (Sangley) in Precolonial/Early Spanish Philippines, c. 1590 via Boxer Codex

-

Chinese (Sangley) Couple Migrants in the Philippines, c. 1590

-

Chinese (Sangley) Couple Migrants in the Philippines, c. 1590

-

Ming dynasty Chinese General with Attendant, c. 1590

-

Mandarin Bureaucrat with Wife from Ming dynasty, c. 1590

-

Chinese nobility from Ming Dynasty China, c. 1590

Spanish colonization of the Philippines (16th century–1898)

When the Spaniards arrived in the Philippines, there was already a significant population of migrants from China all of whom were male due to the relationship between the barangays (city-states) of the island of Luzon and the Ming dynasty.[citation needed]

The first encounter of the Spanish authorities with the Chinese occurred when several Chinese pirates under the leadership of Limahong attacked and besieged the newly established capital of Manila in 1574. The pirates tried to capture the city but were defeated by the combined Spanish and native forces under the leadership of Juan de Salcedo in 1575. Almost simultaneously, the Chinese imperial admiral Homolcong arrived in Manila where he was well received. On his departure he took with him two priests, who became the first Catholic missionaries in China sent from the Philippines. This visit was followed by the arrival of Chinese ships in Manila in May 1603 bearing Chinese officials with the seal of the Ming Empire. This led to suspicions that the Chinese had sent a fleet to try to conquer the islands. However, seeing the city's strong defenses, the Chinese made no hostile moves.[citation needed] They returned to China without showing any particular motive for the journey and without either side mentioning the apparent motive.[citation needed] Fortifications of Manila were started, with a Chinese settler in Manila named Engcang, who offered his services to the governor.[citation needed] He was refused and a plan to massacre the Spaniards quickly spread among the Chinese inhabitants of Manila. The revolt was quickly crushed by the Spaniards, ending in a large-scale massacre of the non-Catholic Sangley in Manila.

The Spanish authorities started restricting the activities of the Chinese immigrants and confined them to the Parían near Intramuros. With low chances of employment and prohibited from owning land, most of them engaged in small businesses or acted as skilled artisans to the Spanish colonial authorities.

The Spanish authorities differentiated the Chinese immigrants into two groups: Parían (unconverted) and Binondo (converted).[

Chinese mestizos as Filipinos

During the

Chinese mestizos in the Visayas

Sometime in the year 1750, an adventurous young man named Wo Sing Lok, also known as "Sin Lok" arrived in Manila, Philippines. The 12-year-old traveler came from Amoy, the old name for Xiamen, an island known in ancient times as "Gateway to China"—near the mouth of Jiulong "Nine Dragon" River in the southern part of Fujian Province.

Earlier in Manila, immigrants from China were herded to stay in the Chinese trading center called "Parian". After the Sangley Revolt of 1603, this was destroyed and burned by the Spanish authorities. Three decades later, Chinese traders built a new and bigger Parian near Intramuros.

For fear of a Chinese uprising similar to that in Manila, the Spanish authorities implementing the royal decree of Gov. Gen. Juan de Vargas dated July 17, 1679, rounded up the Chinese in Iloilo and hamletted them in the parian (now Avanceña Street). It compelled all local unmarried Chinese to live in the Parian and all married Chinese to stay in Binondo. Similar Chinese enclaves or "Parian" were later established in Camarines Sur, Cebu and Iloilo.[25]

Sin Lok together with the progenitors of the Lacson, Sayson, Ditching, Layson, Ganzon, Sanson and other families who fled Southern China during the reign of the despotic Qing dynasty (1644–1912) in the 18th century and arrived in Maynilad; finally, decided to sail farther south and landed at the port of Batiano river to settle permanently in "Parian" near La Villa Rica de Arevalo in Iloilo.[26][27]

American colonial era (1898–1946)

During the American colonial period, the Chinese Exclusion Act in the United States was also put into effect in the Philippines.[28] Nevertheless, the Chinese were able to settle in the Philippines with the help of other Chinese Filipinos, despite strict American law enforcement, usually through "adopting" relatives from Mainland or by assuming entirely new identities with new names.

The privileged position of the Chinese as middlemen of the economy under Spanish colonial rule[29] quickly fell, as the Americans favored the principalía (educated elite) formed by Chinese mestizos and Spanish mestizos. As American rule in the Philippines started, events in Mainland China starting from the Taiping Rebellion, Chinese Civil War and Boxer Rebellion led to the fall of the Qing dynasty, which led thousands of Chinese from Fujian Province in China to migrate en masse to the Philippines to avoid poverty, worsening famine and political persecution. This group eventually formed the bulk of the current population of unmixed Chinese Filipinos.[24]

Formation of the Chinese Filipino identity (1946–1975)

Beginning in

Chinese as aliens under the Marcos regime (1975–1986)

Under the administration of

Chinese schools in the Philippines, which were governed by the

Following the February 1986

Return of democracy (1986–2000)

Despite getting better protections, crimes against Chinese Filipinos were still present, the same way as crimes against other ethnic groups in the Philippines, as the country was still battling the lingering economic effects of the Marcos regime.[citation needed][34][35] All these led to the formation of the first Chinese Filipino organization, Kaisa Para Sa Kaunlaran, Inc. (Unity for Progress) by Teresita Ang-See[b] which called for mutual understanding between the ethnic Chinese and the native Filipinos. Aquino encouraged free press and cultural harmony, a process which led to the burgeoning of the Chinese-language media[36] During this time, the third wave of Chinese migrants came. They are known as the "xin qiao" (Mandarin simplified Chinese: 新侨; traditional Chinese: 新僑; pinyin: xīn qiáo; lit. 'new sojourner'), tourists or temporary visitors with fake papers, fake permanent residencies or fake Philippine passports that started coming starting the 1990s during the administration of Fidel Ramos and Joseph Estrada.[31]

21st century (2001–present)

More Chinese Filipinos were given Philippine citizenship during the 21st century. Chinese influence in the country increased during the pro-China presidency of Gloria Arroyo.[37] Businesses by Chinese Filipinos were said to have improved under Benigno Aquino's presidency, while mainland Chinese migration into the Philippines decreased due to Aquino's pro-Filipino and pro-American approach in handling disputes with China.[38] "Xin qiao" Chinese migration from mainland China into the Philippines intensified from 2016 up to the present,[31] due to controversial pro-China policies by the Rodrigo Duterte presidency, prioritizing Chinese POGO businesses.[39]

The Chinese Filipino community have expressed concerns over the ongoing disputes between China and the Philippines, which majority preferring peaceful approaches to the dispute to safeguard their own private businesses.[31][40]

Origins

Most Chinese Filipinos in the Philippines belong to Hokkien-speaking group of the Han Chinese ethnicity. Many Chinese Filipinos are either fourth-, third-, or second-generation; in general natural-born Philippine citizens who can still recognize their Chinese roots and have Chinese relatives in China, as well as in other Southeast Asian, Australasian or North American countries.

According to a study of around 30,000 gravestones in the

Hokkien (Fujianese / Hokkienese / Fukienese / Fookienese) people

Chinese Filipinos who have roots as

The Hokkien-descended Chinese Filipinos currently dominate the light and heavy industries, as well as the entrepreneurial and real estate sectors of the Philippine economy. Many younger Hokkien-descended Chinese Filipinos are also entering the fields of banking, computer science, engineering, finance and medicine.

To date, most emigrants and permanent residents from Mainland China, as well as the vast majority of Taiwanese people in the Philippines are also of Hokkien background.

Teochews

Linguistically related to the Hokkien people are the

: Cháozhōurén).They migrated in large numbers to the Philippines during the Spanish Period to the main Luzon island of the Philippines, such as the famed smuggler, Limahong (林阿鳳), and his followers who were originally from Raoping, Chaozhou,[43] but later on were eventually assimilated by intermarriage with the mainstream Hokkien.

The Teochews are often mistaken for being Hokkien.

Cantonese people

Chinese Filipinos who have roots as Cantonese people (Cantonese Chinese: 廣府人; Cantonese Yale: Gwóng fú yàhn) have ancestors who came from Guangdong Province and speak or at least have Cantonese or Taishanese as heritage language. They settled down in Metro Manila, as well as in major cities of Luzon such as Baguio City, Angeles City, Naga and Olongapo. Many also settled in the provinces of Northern Luzon (e.g., Benguet, Cagayan, Ifugao, Ilocos Norte) especially around Baguio.[44] Examples of those of Cantonese descent are people like Ma Mon Luk, the Tecson and Ticzon families descended from the three "Tek Sun" brothers from Guangzhou (Canton), Guangdong.

The

Others

There are also some ethnic Chinese from neighboring Asian countries and territories, most notably from

Temporary resident Chinese businessmen and envoys include people from Beijing, Shanghai and other major cities and provinces throughout China.

Chinese Moro mestizos

The Chinese Moro mestizos are of paternal Han Chinese descent who married Moro Muslim women from Tausug, Sama and Maguindanaon ethnicities and are not descendants of Hui Muslims. The Moros did not follow Sharia prohibitions on marriage of Muslim women to non-Muslims. So, Han Chinese men from the Straits Settlements and the Chinese mainland migrated to Mindanao (and the islands of Sulu) and founded families. These mestizos celebrated Chinese New Year and Chinese holidays including ones of pagan origin and practice Han cultural taboos; like the taboo against patrilineal cousin marriage. Hui in China practice marriage of patrilineal cousins of the same surname to each other, which the Han-descended Chinese Moro mestizos do not. Observant Hui Muslims also do not practice Chinese pagan holidays. The Han men continued practicing their own pagan religions and holidays when married to Moro Muslim women. As late as the 1970s, Professor Samuel Kong Tan said among the Chinese and Moros of Sulu, it was still normal for non-Muslim men to marry Muslim women.

The Han who became part of the Chinese-Moro mestizo community are mostly of Minnan background, either directly from southern Fujian like Xiamen (Amoy) or the Peranakans who are descendants of Minnan speaking Han men and Malay women, with a small minority of them being descendants of other Han like one northern Han family who married into the Tausug. Some Han of either Hakka or Cantonese background in Sabah, Borneo married Tausug women there before World War II ended.

The Chinese families among the Tausug include the Kho, Lim, Teo, Kong and multiple families with the surname Tan, including the family of Tuchay Tan and Hadji Suug Tan. These families maintain the Chinese practice of not permitting marriages in the same paternal families with the same surname, and even though the Tans are multiple families, they still adhere to the rule of avoiding marriage to each other believing they were related far in the past.

The assimilation and intermarriages between the local Muslim Moro Tausug and Sama in Sulu and the Han Chinese immigrants, in contrast to Chinese living in Filipino Catholic areas, was facilitated by the good relations throughout history between China and Sulu.[46][47]

The Chinese mestizo descendants of Han Chinese men and Moro Muslim Tausug and Sama women are integrating and dissolving into the Tausug and Sama population as they lose practice of Chinese culture except celebrating some festivals and their Chinese names.[48][49][50][51][52]

Demographics

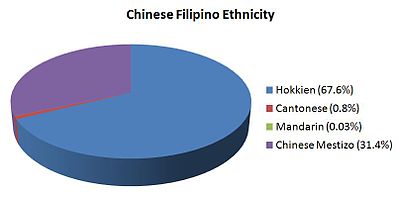

| Dialect | Population[citation needed][53][54] |

|---|---|

Hokkienese

|

1,044,000 |

| Cantonese | 13,000 |

| Mandarin | 550 |

Chinese mestizo *

|

486,000 |

- The figure above denotes first-generation Chinese mestizos – namely, those with one Chinese and one Filipino parent. This figure does not include those who have less than 50% Chinese ancestry, who are mostly classified as "Filipino".

The exact number of all Filipinos with some Chinese ancestry is unknown. Various estimates have been given from the start of the Spanish Colonial Period up to the present ranging from as low as 1% to as large as 18–27%. The National Statistics Office does not conduct surveys of ethnicity.[55]

According to a research report by historian Austin Craig who was commissioned by the United States in 1915 to ascertain the total number of the various races of the Philippines, the pure Chinese, referred to as Sangley, number around 20,000 (as of 1918), and that around one-third of the population of Luzon have partial Chinese ancestry. This comes with a footnote about the widespread concealing and de-emphasising of the exact number of Chinese in the Philippines.[56]

Another source dating from the Spanish Colonial Period shows the growth of the Chinese and the Chinese mestizo population to nearly 10% of the Philippine population by 1894.

| Race | Population (1810) | Population (1850) | Population (1894) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Malay (i.e., indigenous Filipino) | 2,395,677 | 4,725,000 | 6,768,000 |

| mestizo de sangley (i.e., Chinese mestizo) | 120,621 | 240,000 | 500,000 |

| sangley (i.e., Unmixed Chinese) | 7,000 | 25,000 | 100,000 |

| Peninsular (i.e., Spaniard) | 4,000 | 10,000 | 35,000 |

| Total | 2,527,298 | 5,000,000 | 7,403,000 |

Language

The vast majority (74.5%) of Chinese Filipinos, especially those in Metro Manila and surrounding regions, speak Filipino (Tagalog) and/or Philippine English as their native language. Most Chinese Filipinos (77%) still retain the ability to understand and speak Hokkien as a second or third language.[57]

The use of Hokkien as a first language is seemingly confined to the older generation and to Chinese Filipino families living in traditional Chinese Filipino centers, such as Caloocan, Davao Chinatown, and the Binondo district of Manila. In part due to the increased adoption of Philippine nationality during the Marcos era, most Chinese Filipinos born from the 1970s to the mid-1990s tend to use English, Filipino (Tagalog) and perhaps other Philippine regional languages, which they frequently code-switch between as Taglish or mix together with Hokkien as Hokaglish. Among the younger generation (born from the mid-1990s onward), the preferred language is often English besides also, of course, knowing Filipino (Tagalog) and, in most regions of the Philippines, other regional languages.[58] Recent arrivals from Mainland China or Taiwan, despite coming mostly from traditionally Hokkien-speaking areas, typically use Mandarin among themselves.

Unlike other overseas Chinese communities in

For the

Hokkien / Fukien / Fookien (Philippine Hokkien)

Since most Chinese Filipinos in the Philippines trace their ancestry to

The variant of

The Chinese Sangley community in the Philippines centuries ago during Spanish colonial times spoke a mix of different Hokkien dialects (Zhangzhou/Chiangchiu, Quanzhou/Chuanchiu, Amoy/Xiamen), enough that the Hokkien recorded by the Spaniards during the early 1600s, such as in the Dictionario Hispanico Sinicum (1604), resembled the Zhangzhou dialect more,[60] contrary to the modern 21st century Philippine Hokkien that now resembles the Quanzhou dialect more.[61]

Mandarin

Mandarin is currently the subject and medium of instruction for teaching Standard Chinese (Mandarin) class subjects in Chinese Filipino schools in the Philippines. However, since the language is rarely used outside of the classroom besides jobs and interactions related to Mainland China and Taiwan, most Chinese Filipinos would be hard-pressed to converse in Mandarin.

As a result of longstanding influence from the

Spanish Dominican Catholic missionaries like Francisco Varo who visited 17th century Fujian (late Ming and early Qing) learned both local Min Chinese and the official Ming dynasty Mandarin Chinese (guanhua) and they explicitly noted that Mandarin was regarded as an elegant, "elevated" language by the local Fujianese Chinese while their own local Min speech were regarded as "coarse speech". They noted Mandarin Guanhua was solemn and used by the educated Fujianese literati and officials while it was the rural villagers and women who only spoke the local Min patois (xiangtan) since they didn't speak Mandarin.[62] Jesuits in Ming dynasty China like Matteo Ricci generally focused on studying the official and prestigious Mandarin while Dominicans studied vernacular Hokkien dialects in Fujian.[63]

Cantonese and Taishanese

Currently, there are still a few minority

English

Just like most other

Filipino and other Philippine languages

The majority of Chinese Filipinos who were born, were raised, or have lived long enough in the Philippines are at least natively

Many Chinese Filipinos, especially those living in the

Spanish

During the

Religion

Chinese Filipinos are unique in Southeast Asia in being overwhelmingly Christian (83%).[57] but many families, especially Chinese Filipinos in the older generations still practice traditional Chinese religions. Almost all Chinese Filipinos, including the Chinese mestizos but excluding recent migrants from either Mainland China or Taiwan, had or will have their marriages in a Christian church.[57]

In the 18th century, many Chinese converted from traditional religions to Catholicism.[65]

Roman Catholicism

The majority (70%) of Christian Chinese Filipinos are

Unique to the Catholicism of Chinese Filipinos is the religious syncretism that is found in Chinese Filipino homes. Many have altars bearing Catholic images such as the

Protestantism

Approximately 13% of all Christian Chinese Filipinos are Protestants.[67]

Many Chinese Filipino schools are founded by Protestant missionaries and churches.

Chinese Filipinos comprise a large percentage of membership in some of the largest

In contrast to Roman Catholicism, Protestantism forbids traditional Chinese practices such as ancestor veneration, but allows the use of meaning or context substitution for some practices that are not directly contradicted in the Bible (e.g., celebrating the Mid-Autumn Festival with moon cakes denoting the moon as God's creation and the unity of families, rather than the traditional Chinese belief in Chang'e). Many also had ancestors already practicing Protestantism while still in China.

Unlike native and mestizo Filipino-dominated Protestant churches in the Philippines which have very close ties with North American organizations, most Protestant Chinese Filipino churches instead sought alliance and membership with the Chinese Congress on World Evangelization, an organization of Overseas Chinese Christian churches throughout Asia.[69]

Chinese traditional religions and practices

A small number of Chinese Filipinos (2%) continue to practise

Buddhist and Taoist temples can be found where the Chinese live, especially in urban areas like Manila.

Around half (40%) of all Chinese Filipinos regardless of religion still claim to practise

Chinese traditional religions have been practiced on the Philippines since circa 985.[65]

Others

There are very few Chinese Filipino Muslims, most of whom live in either Mindanao or the Sulu Archipelago and have intermarried or assimilated with their Moro neighbors. Many of them have attained prominent positions as political leaders. They include Datu Piang, Abdusakur Tan and Michael Mastura, among such others.

Others are also members of the Iglesia ni Cristo, Jehovah's Witnesses or the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Some younger generations of Chinese Filipinos also profess to be atheists.[citation needed]

Education

There are 150 Chinese schools that exist throughout the Philippines, slightly more than half of which operate in Metro Manila.[75][76] Chinese Filipino schools typically include the teaching of Standard Chinese (Mandarin), among other school class subjects, and have an international reputation for producing award-winning students in the fields of science and mathematics, most of whom reap international awards in mathematics, computer programming, and robotics Olympiads.[77]

History

The first school founded specifically for the Chinese in the Philippines, the Anglo-Chinese School (now known as

Burgeoning of Chinese schools throughout the Philippines, including in Manila, occurred from the 1920s until the 1970s, with a brief interlude during World War II, when all Chinese schools were ordered closed by the

Such a situation continued until 1973, when amendments made during the

The changes in Chinese education initiated with the 1973 Philippine Constitution led to a large shifting of mother tongues, reflecting the assimilation of the Chinese Filipinos into general Philippine society. The older generation of Chinese Filipinos, who were educated in the old curriculum, typically use Philippine Hokkien at home, while most younger-generation Chinese Filipinos are more comfortable conversing in English, Filipino (Tagalog), and/or other Philippine languages like Cebuano, including their code-switching forms like Taglish and Bislish, which are sometimes varyingly admixed with Philippine Hokkien to make Hokaglish.

Curriculum

Chinese Filipino schools typically feature curriculum prescribed by the Philippine Department of Education (DepEd). The limited time spent in Chinese instruction consists largely of language arts.

The three core Chinese subjects are "Chinese Grammar" (simplified Chinese: 华语; traditional Chinese: 華語; pinyin: Huáyǔ; Pe̍h-ōe-jī: Hoâ-gí; Zhuyin Fuhao: ㄏㄨㄚˊ ㄩˇ; lit. 'Chinese Language'), "Chinese Composition" (Chinese: 綜合; pinyin: Zònghé; Pe̍h-ōe-jī: Chong-ha̍p; Zhuyin Fuhao: ㄗㄨㄥˋ ㄏㄜˊ; lit. 'Composition'), and "Chinese Mathematics" (Chinese: 數學; pinyin: Shùxué; Pe̍h-ōe-jī: Sò͘-ha̍k; Zhuyin Fuhao: ㄨˋ ㄒㄩㄝˊ; lit. 'Mathematics'). Other schools may add other subjects such as "Chinese Calligraphy" (Chinese: 毛筆; pinyin: Máobǐ; Pe̍h-ōe-jī: Mô͘-pit; Zhuyin Fuhao: ㄇㄠˊ ㄅㄧˇ; lit. 'Calligraphy Brush'). Chinese history, geography and culture are also integrated in all the three core Chinese subjects – they stood as independent subjects of their own before 1973. Many schools currently teach at least just one Chinese subject, known simply as just "Chinese" (simplified Chinese: 华语; traditional Chinese: 華語; pinyin: Huáyǔ; Pe̍h-ōe-jī: Hoâ-gí; Zhuyin Fuhao: ㄏㄨㄚˊ ㄩˇ; lit. 'Chinese Language'). It also varies per school if either or both Traditional Chinese with Zhuyin (known in many schools in Hokkien Chinese: 國音; Pe̍h-ōe-jī: kok-im) and/or Simplified Chinese with Pinyin is taught. Currently, all Chinese class subjects are taught in Mandarin Chinese (known in many schools in Hokkien Chinese: 國語; Pe̍h-ōe-jī: kok-gí) and in some schools, students are prohibited from speaking any other language, such as English, Filipino (Tagalog), other regional Philippine languages, or even Hokkien during Chinese classes, when decades before, there were no such restrictions.

Schools and universities

Many Chinese Filipino schools are sectarian, being founded by either

Major non-sectarian schools include

Most Chinese Filipinos attend Chinese Filipino schools until Secondary level and then transfer to non-Chinese colleges and universities to complete their tertiary degree, due to the dearth of Chinese language tertiary institutions.

Name format

Many Chinese who lived during the Spanish naming edict of 1849 eventually adopted Spanish name formats, along with a Spanish given name (e.g., Florentino Cu y Chua).[

Newer Chinese migrants who came during the American Colonial Period use a combination of an adopted Spanish (or rarely, English) name together with their Chinese name (e.g., Carlos Palanca Tan Quin Lay or Vicente Go Tam Co).[citation needed] This trend was to continue up to the late 1970s.

As both exposure to North American media as well as the number of Chinese Filipinos educated in English increased, the use of English names among Chinese Filipinos, both common and unusual, started to increase as well. Popular names among the second generation Chinese community included English names ending in "-son" or other Chinese-sounding suffixes, such as Anderson, Emerson, Jackson, Jameson, Jasson, Patrickson, Washington, among such others. For parents who are already third and fourth generation Chinese Filipinos, English names reflecting American popular trends are given, such as Ethan, Austin and Aidan.

It is thus not unusual to find a young Chinese Filipino, for example, named "Chase Tan", whose father's name is "Emerson Tan" and whose grandfather's name is "Elpidio Tan Keng Kui", reflecting the depth of immersion into the English language as well as into the Philippine society as a whole.[citation needed]

Surnames

Chinese Filipinos whose ancestors came to the Philippines from 1898 onward usually have monosyllabic Chinese surnames. On the other hand, most Chinese ancestors came to the Philippines prior to 1898 usually have multisyllabic surnames such as Gokongwei, Ongpin, Pempengco, Yuchengco, Teehankee and Yaptinchay among such others. These were originally full Chinese names which were transliterated in Spanish orthography and adopted as surnames.

Common single-syllable Chinese Filipino surnames are

pronunciation.On the other hand, most Chinese Filipinos whose ancestors came to the Philippines prior to 1898 use a Hispanicized surname (see below). Many Filipinos who have Hispanicized Chinese surnames are no longer pure Chinese, but are Chinese mestizos.

Hispanized surnames

Chinese Filipinos and Chinese mestizos usually have multisyllabic surnames such as Angseeco (from ang/see/co/kho) Aliangan (from liang/gan), Angkeko, Apego (from ang/ke/co/go/kho), Chuacuco, Chuatoco, Chuateco, Ciacho (from Sia), Cinco (from Go), Cojuangco, Corong, Cuyegkeng, Dioquino, Dytoc, Dy-Cok, Dysangco, Dytioco, Gueco, Gokongwei, Gundayao, Kiamco/Quiamco, Kimpo/Quimpo, King/Quing, Landicho, Lanting, Limcuando, Ongpin, Pempengco, Quebengco, Siopongco, Sycip, Tambengco, Tambunting, Tanbonliong, Tantoco, Tinsay, Tiolengco, Yuchengco, Tanciangco, Yuipco, Yupangco, Licauco, Limcaco, Ongpauco, Tancangco, Tanchanco, Teehankee, Uytengsu and Yaptinchay among such others. These were originally full Hokkien Chinese names which were transliterated in Latin letters with Spanish orthography and adopted as Hispanicized surnames.[79]

There are also multisyllabic Chinese surnames that are Spanish transliterations of Hokkien words. Surnames like Tuazon (Eldest Grandchild, 大孫, Tuā-sun),[80] Tiongson/Tiongzon (Eldest Grandchild, 長孫, Tióng-sun)[81]/(Second/Middle Grandchild, 仲孫, Tiōng-sun),[81] Sioson (Youngest Grandchild, 小孫, Sió-sun), Echon/Ichon/Itchon/Etchon/Ychon (First Grandchild, 一孫, It-sun), Dizon (Second Grandchild, 二孫, Dī-sun), Samson/Sanson (Third Grandchild, 三孫, Sam-sun), Sison (Fourth Grandchild, 四孫, Sì-sun), Gozon/Goson/Gozum (Fifth Grandchild, 五孫, Gǒ͘-sun), Lacson (Sixth Grandchild, 六孫, La̍k-sun), Sitchon/Sichon (Seventh Grandchild, 七孫, Tshit-sun), Pueson (Eighth Grandchild, 八孫, Pueh-sun), Causon/Cauzon (Ninth Grandchild, 九孫, Káu-sun), are examples of transliterations of designations that use the Hokkien suffix -son/-zon/-chon (Hokkien Chinese: 孫; Pe̍h-ōe-jī: sun; lit. 'Grandchild') used as surnames for some Chinese Filipinos who trace their ancestry from Chinese immigrants to the Philippines during the Spanish Colonial Period. The surnames 孫, 仲孫, 長孫 are listed in the classic Chinese text Hundred Family Surnames, perhaps shedding light on the Hokkien suffix -son/-zon/-chon used here as a surname alongside some sort of accompanying enumeration scheme.

The Chinese who survived the massacre in Manila in the 1700s fled to other parts of the Philippines and to hide their identity, some also adopted two-syllable surnames ending in "son" or "zon" and "co" such as: Yanson = Yan = 燕孫, Ganzon = Gan = 颜孫(Hokkien), Guanzon = Guan/Kwan = 关孫 (Cantonese), Tiongson/Tiongzon = Tiong = 仲孫 (Hokkien), Cuayson/Cuayzon = 邱孫 (Hokkien), Yuson = Yu = 余孫, Tingson/Tingzon = Ting = 陈孫 (Hokchew), Siason = Sia = 谢孫 (Hokkien).[82]

Many also took on Spanish or native Filipino surnames (e.g. Alonzo, Alcaraz, Bautista, De la Cruz, De la Rosa, De los Santos, Garcia, Gatchalian, Mercado, Palanca, Robredo, Sanchez, Tagle, Torres, etc.) upon naturalization. Today, it can be difficult to identify who are Chinese Filipino based on surnames alone.

A phenomenon common among Chinese migrants in the Philippines dating from the 1900s would be to purchase their surname, particularly during the American Colonial Period, when the Chinese Exclusion Act was applied to the Philippines. Such law led new Chinese migrants to purchase the Hispanic or native surnames of native and mestizo Filipinos and thus pass off as long-time Filipino residents of Chinese descent or as native or mestizo Filipinos. Many also purchased the Alien Landing Certificates of other Chinese who have gone back to China and assumed his surname and/or identity. Sometimes, younger Chinese migrants would circumvent the Act through adoption – wherein a Chinese with Philippine nationality adopts a relative or a stranger as his own children, thereby giving the adoptee automatic Filipino citizenship – and a new surname.[citation needed]

Food

Traditional Tsinoy cuisine, as Chinese Filipino home-based dishes are locally known, make use of recipes that are traditionally found in China's Fujian Province and fuse them with locally available ingredients and recipes. These include unique foods such as hokkien chha-peng (Fujianese-style fried rice), si-nit mi-soa (birthday noodles), pansit canton (Fujianese-style e-fu noodles), hong ma or humba (braised pork belly), sibut (four-herb chicken soup), hototay (Fujianese egg drop soup), kiampeng (Fujianese beef fried rice), machang (glutinous rice with adobo) and taho (a dessert made of soft tofu, arnibal syrup and pearl sago).

However, most Chinese restaurants in the Philippines, as in other places, feature

Politics

With the increasing number of Chinese with Philippine nationality, the number of political candidates of Chinese-Filipino descent also started to increase. The most significant change within Chinese Filipino political life would be the citizenship decree promulgated by former President Ferdinand Marcos which opened the gates for thousands of Chinese Filipinos to formally adopt Philippine citizenship.

Chinese Filipino political participation largely began with the People Power Revolution of 1986 which toppled the Marcos dictatorship and ushered in the Aquino presidency. The Chinese have been known to vote in blocs in favor of political candidates who are favorable to the Chinese community.

Important Philippine political leaders with Chinese ancestry include the current president

.The former

also have Chinese ancestry.Society and culture

Society

The Chinese Filipino are mostly business owners[according to whom?] and their life centers mostly in the family business. These mostly small or medium enterprises play a significant role in the Philippine economy. A handful of these entrepreneurs run large companies and are respected as some of the most prominent business tycoons in the Philippines.

Chinese Filipinos attribute their success in business to frugality and hard work, Confucian values and their traditional Chinese customs and traditions. They are very business-minded and entrepreneurship is highly valued and encouraged among the young. Most Chinese Filipinos are urban dwellers. An estimated 50% of the Chinese Filipino live within Metro Manila, with the rest in the other major cities of the Philippines. In contrast with the Chinese mestizos, few Chinese are plantation owners. This is partly due to the fact that until recently when the Chinese Filipino became Filipino citizens, the law prohibited the non-citizens, which most Chinese were, from owning land.

Culture

As with other Southeast Asian nations, the Chinese community in the Philippines has become a repository of traditional Chinese culture common to unassimilated ethnic minorities throughout the world. Whereas in mainland China many cultural traditions and customs were suppressed or destroyed during the Cultural Revolution or simply regarded as old-fashioned nowadays, these traditions have remained largely preserved in the Philippines.[citation needed]

Many new cultural twists have evolved within the Chinese community in the Philippines, distinguishing it from other overseas Chinese communities in Southeast Asia. These cultural variations are highly evident during festivals such as Chinese New Year and Mid-Autumn Festival. The Chinese Filipino have developed unique customs pertaining to weddings, birthdays and funerary rituals.[citation needed]

Weddings

Wedding traditions of Chinese Filipinos, regardless of religious persuasion, usually involve identification of the dates of supplication or pamamanhikan (kiu-hun), engagement (ting-hun) and wedding (kan-chhiu) adopted from Filipino customs. In addition, feng shui based on the birthdates of the couple, as well as of their parents and grandparents may also be considered. Certain customs found among Chinese Filipinos include during supplication (kiu-hun) also include a solemn tea ceremony within the house of the bridegroom ensues where the couple will be served tea, egg noodles (misua) and given red packets or envelopes containing money, commonly referred to as an ang-pao.[citation needed]

During the supplication ceremony, pregnant women and recently engaged couples are forbidden from attending the ceremony. Engagement (ting-hun) quickly follows, where the bride enters the ceremonial room walking backward and turned three times before being allowed to see the groom. A welcome drink consisting of red-colored juice is given to the couple, quickly followed by the exchange of gifts for both families and the wedding tea ceremony, where the bride serves the groom's family and vice versa. The engagement reception consists of sweet tea soup and misua, both of which symbolizes long-lasting relationship.[citation needed]

Before the wedding, the groom is expected to provide the matrimonial bed in the future couple's new home. A baby born under the Chinese sign of the Dragon may be placed in the bed to ensure fertility. He is also tasked to deliver the wedding gown to his bride on the day prior to the wedding to the sister of the bride, as it is considered ill fortune for the groom to see the bride on that day. For the bride, she prepares an initial batch of personal belongings (ke-chheng) to the new home, all wrapped and labeled with the Chinese characters for sang-hi. On the wedding date, the bride wears a red robe emblazoned with the emblem of a dragon prior to wearing the bridal gown, to which a pair of sang-hi (English: marital happiness) coin is sewn. Before leaving her home, the bride then throws a fan bearing the Chinese characters for sang-hi toward her mother to preserve harmony within the bride's family upon her departure. Most of the wedding ceremony then follows Catholic or Protestant traditions.[citation needed]

Post-wedding rituals include the two single brothers or relatives of the bride giving the couple a wa-hoe set, which is a bouquet of flowers with umbrella and sewing kit, for which the bride gives an ang-pao in return. After three days, the couple then visits the bride's family, upon which a pair of sugar cane branch is given, which is a symbol of good luck and vitality among Hokkien people.[83]

Births and birthdays

Birthday traditions of Chinese Filipinos involve large banquet receptions, always featuring noodles[d] and round-shaped desserts. All the relatives of the birthday celebrant are expected to wear red clothing which symbolize respect for the celebrant. Wearing clothes with a darker hue is forbidden and considered bad luck. During the reception, relatives offer ang paos (red packets containing money) to the birthday celebrant, especially if he is still unmarried. For older celebrants, boxes of egg noodles (misua) and eggs on which red paper is placed are given.[citation needed]

Births of babies are not celebrated and they are usually given pet names, which he keeps until he reaches first year of age. The Philippine custom of circumcision is widely practiced within the Chinese Filipino community regardless of religion, albeit at a lesser rate as compared to native Filipinos. First birthdays are celebrated with much pomp and pageantry, and grand receptions are hosted by the child's paternal grandparents.[citation needed]

Funerals and burials

Funerary traditions of Chinese Filipinos mirror those found in Southern Fujian. A unique tradition of many Chinese Filipino families is the hiring of professional mourners which is alleged to hasten the ascent of a dead relative's soul into Heaven. This belief particularly mirrors the merger of traditional Chinese beliefs with the Catholic religion.[84]

Subcultures

Most of the Chinese mestizos, especially the landed gentry trace their ancestry to the Spanish era. They are the "First Chinese" or Sangley whose descendants nowadays are mostly integrated into Philippine society. Most are from Zhangzhou, Fujian province in China, with a minority coming from Guangdong. They have embraced a Hispanized Filipino culture since the 17th century. After the end of Spanish rule, their descendants, the Chinese mestizos, managed to invent a cosmopolitan mestizo culture[citation needed] coupled with an extravagant Mestizo de Sangley lifestyle, intermarrying either with native Filipinos or with Spanish mestizos.

The largest group of Chinese in the Philippines are the "Second Chinese", who are descendants of migrants in the first half of the 20th century, between the anti-Qing 1911 Revolution in China and the Chinese Civil War. This group accounts for most of the "full-blooded" Chinese. They are almost entirely from Fujian Province.

The "Third Chinese" are the second largest group of Chinese, the recent immigrants from Mainland China, after the Chinese economic reform of the 1980s. Generally, the "Third Chinese" are the most entrepreneurial and have not totally lost their Chinese identity in its purest form and seen by some "Second Chinese" as a business threat. Meanwhile, continuing immigration from Mainland China further enlarge this group[85]

Civic organizations

Aside from their family businesses, Chinese Filipinos are active in Chinese-oriented civic organizations related to education, health care, public safety, social welfare and public charity. As most Chinese Filipinos are reluctant to participate in politics and government, they have instead turned to civic organizations as their primary means of contributing to the general welfare of the Chinese community. Beyond the traditional family and clan associations, Chinese Filipinos tend to be active members of numerous alumni associations holding annual reunions for the benefit of their Chinese-Filipino secondary schools.[86]

Outside of secondary schools catering to Chinese Filipinos, some Chinese Filipinos businessmen have established charitable foundations that aim to help others and at the same time minimize tax liabilities. Notable ones include the Gokongwei Brothers Foundation, Metrobank Foundation, Tan Yan Kee Foundation, Angelo King Foundation, Jollibee Foundation, Alfonso Yuchengco Foundation, Cityland Foundation, etc. Some Chinese-Filipino benefactors have also contributed to the creation of several centers of scholarship in prestigious Philippine Universities, including the John Gokongwei School of Management at Ateneo de Manila, the Yuchengco Center at

Ethnic Chinese Filipinos' perceptions of non-Chinese Filipinos

Non-Chinese Filipinos were initially referred to as

Some Chinese Filipinos perceive the government and authorities to be unsympathetic to the plight of the ethnic Chinese, especially in terms of frequent kidnapping for ransom during the late 1990s.[94] Currently, most of the third or fourth generation Chinese Filipinos generally view the non-Chinese Filipino people and government positively, and have largely forgotten about the historical oppression of the ethnic Chinese. They are also most likely to consider themselves as just being "Filipino" and focus on the Philippines, rather than on just being "Chinese" and being associated with China (PRC) or Taiwan (ROC).

Some Chinese Filipinos believe racism still exists toward their community among a minority of non-Chinese Filipinos, who the Chinese Filipinos refer to as "pâi-huâ" (

Intermarriage

Chinese mestizos are persons of mixed Chinese and either Spanish or indigenous Filipino ancestry. Mestizos are thought to make up as much as 25% of the country's total population. A number of Chinese mestizos have surnames that reflect their heritage, mostly two or three syllables that have Chinese roots (e.g., the full name of a Chinese ancestor) with a Hispanized phonetic spelling.

During the Spanish colonial period, the Spanish authorities encouraged the Chinese male immigrants to convert to Catholicism. Those who converted got baptized and their names Hispanized, and were allowed to intermarry with indigenous Filipino women. The couple and their mestizo offspring became colonial subjects of the Spanish crown, and as such were granted several privileges and afforded numerous opportunities that were denied to the unconverted and non-citizen Chinese. Starting out as traders, many Chinese mestizo businesspeople branched out into land leasing, money-lending, and later, landholding.

Chinese mestizo men and women were encouraged to marry Spanish and indigenous women and men,[citation needed] by means of dowries,[citation needed] as part of a colonial policy to mix the different ethno-racial groups of the Philippines so as it would be impossible to expel the Spanish.[103]

In these days however, blood purity was still of prime concern in most traditional Chinese Filipino families especially pure-blooded Han ones. Many Chinese Filipinos held the belief that a Chinese Filipino can only be married to another fellow Chinese Filipino since marriages to a non-Chinese Filipino or any non-Chinese outsider was considered taboo. Chinese marriage to native or mestizo Filipinos and outsiders still continues posts uncertainty on both parties to this day. As the Chinese Filipino family structure is traditionally patriarchal hence, it is the male that carries the last name of the family which also entails the pedigree and legacy of the family name itself. Male Chinese Filipino marriage to a native or mestiza Filipina or any outsider was considered to be more admissible than vice versa. In the case of the Chinese Filipina female marrying a native or mestizo Filipino or any outsider, it may cause several unwanted racial issues and tensions, especially on the side of the Chinese family.

In some instances, a member of a traditional Chinese Filipino family may be denied of his or her inheritance and likely to be disowned by his or her family for marrying an outsider without their consent. However, there are exceptions in which intermarriage to a non-Chinese Filipino or any outsider is permissible provided their family background is socioeconomically well-off or influential.

On the other hand, modern Chinese Filipino families who exhibit more liberal cosmopolitan views and beliefs are generally more receptive to interracial marriage by allowing their children to marry native or mestizo Filipino or any non-Chinese outsider. However, many contemporary Chinese Filipino families would still by and large prefer that the Filipino or any non-Chinese outsider would have some or little Han Chinese ancestry, such as the descendants of Chinese mestizos dating back to the Spanish colonial period.

Trade and industry

Like much of Southeast Asia, Filipinos of Chinese ancestry dominate the Filipino economy and commerce at every level of society.[9][111][112] Chinese Filipinos wield tremendous economic clout unerringly disproportionate relative to their small population size over their indigenous Filipino majority counterparts and play a critical role in maintaining the country's economic vitality and prosperity.[113][11][114] With their powerful economic prominence, the Chinese virtually make up the country's entire wealthy elite.[104][115][116] Chinese Filipinos, in the aggregate, represent a disproportionate wealthy, market-dominant minority not only form a distinct ethnic community, they also form, by and large, an economic class: the commercial middle and upper class in contrast to their poorer indigenous Filipino majority working and underclass counterparts around them.[9][116] Entire posh Chinese enclaves have sprung up in major Filipino cities across the country, literally walled off from the poorer indigenous Filipino masses guarded by heavily armed, private security forces.[9] Though the contemporary Chinese Filipino community albeit remains stubbornly insular, given their propensity to voluntarily segregate themselves from the indigenous Filipino populace through typically associating themselves with the Chinese community, their collective impacting presence nonetheless still remains powerfully felt throughout the country at large. In particular, given their dominant middleman minority status and ubiquitous economic influence and prosperity owing to their shrewd business acumen and astute investment savvy have prompted the community's acculturation into mainstream Filipino society and their maintenance of their exclusively unabashed distinctive cultural sense of ethnic identity, clannishness, community, kinship, nationalism, and socioethnic cohesion through clan associations.[117]

The Chinese have played a key role in Filipino business and industry having dominated the economy of the Philippines for centuries long before the pre-Spanish and American colonial eras.

Up until the 1970s, many of the Philippines's biggest corporations and commercial economic activities had long been under the control, influence, and ownership of the Americans and Spaniards.[123] Since the 1970s, much of the Philippines's economic activities that were once long held by them have increasingly come under the commercial influencing dominance of the Chinese, where Filipinos of Chinese ancestry are estimated to control 60 to 70 percent of the modern Filipino economy.[124][125][126][127][128][129][10][130][131][132][133][134][135][136][137][138] The Chinese Filipino community, amounting to 1 percent of the overall population of the Philippines, control the country's largest and most lucrative department stores, supermarkets, hotels, shopping malls, airlines, and fast-food restaurants in addition to all of its major financial services providers, banks and stock brokerage houses, as well as dominating the nation's wholesale distribution networks, shipping lines, banks, construction, textiles, real estate, personal computer, semiconductors, pharmaceutical, mass media, and industrial manufacturing industries.[139][140][141][10][104][142] Filipinos of Chinese ancestry also control 40 percent of the Philippine's national corporate equity.[143][144] Filipinos of Chinese ancestry are also involved in the processing and distribution of pharmaceutical products. More than 1000 companies are involved in this industry, with most being small and medium-sized businesses amounting to an aggregate capitalization of ₱1.2 billion.[145] Filipinos of Chinese ancestry are also prominent players in the Filipino mass media industry, as the Chinese control six out of the ten English-language newspapers in Manila, including the one with the largest daily circulation.[104][146] Many retail stores and restaurants presided by Filipino owners with Chinese ancestry are regularly featured in Manila newspapers which often attracted great public interest as such examples of high profile business ownership were used to illustrate the Chinese community's strong economic influence that permeated throughout the country.[147][148] The Chinese also dominate the Filipino telecommunications industry, where one of the current significant players in the Filipino telecom sector was the business taipan John Gokongwei, whose conglomerate JG Summit Holdings controlled 28 wholly-owned subsidiaries with interests ranging from food and agro-industrial products, hotels, insurance agencies, financial services providers, electronic components, textiles and garment manufacturing, real estate, petrochemicals, power generation, printing, newspaper publishing, packaging materials, detergents, and cement mixing.[149] Gokongwei's family firm is one of the six largest and most well-known Filipino conglomerates that has been under the hands of an owner of Chinese lineage.[150] Gokongwei began his business career by starting out in food processing during the 1950s, venturing into textile manufacturing in the early 1970s, and then cornered the Filipino real estate development and hotel management industries by the end of the decade. In 1976, Gokongwei established Manila Midtown Hotels and has since then assumed the controlling interest of two other hotel chains, Cebu Midtown and Manila Galleria Suites respectively.[151] In addition, Gokongwei has also made forays into the Filipino financial services sector as he expanded his business interests by investing in two Filipino banks, PCI Bank and Far East Bank, in addition to negotiating the acquisition of one of the Philippines's oldest newspapers, The Manila Times.[152][153] Gokongwei's eldest daughter became publisher of the newspaper in December 1988 at the age of 28, at which during the same time her father acquired the paper from the Roceses, a Spanish Mestizo family.[154] Of the 66 percent remaining part of the economy in the Philippines held by either Chinese or indigenous Filipinos, the Chinese control 35 percent of all total sales.[155][156] Filipinos of Chinese ancestry control an estimated 50 to 60 percent of non-land share capital in the Philippines, and as much as 35 percent of total sales are attributed to the largest public and private firms owned by the Chinese.[157][158][159][160] Many prominent Filipino companies that are Chinese-owned focus on diverse industry sectors such as semiconductors, chemicals, real estate, engineering, construction, fibre-optics, textiles, financial services, consumer electronics, food, and personal computers.[161] A third of the top 500 companies publicly listed on the Philippines Stock Exchange are owned by Filipinos of Chinese ancestry.[162] Of the top 1000 firms, Filipinos of Chinese ancestry control 36 percent of them and among the top 100 companies, 43 percent.[162][163] Between 1978 and 1988, 146 of the country's 494 top companies were under Chinese ownership.[164] Filipinos of Chinese ancestry are also estimated to control over one-third of the Philippines's 1000 largest corporations with the Chinese controlling 47 of the 68 locally owned companies publicly listed on the Manila Stock Exchange.[165][166][167][168][169][170] In 1990, the Chinese controlled 25 percent of the top 100 businesses in the Philippines and by 2014, the share of top 100 firms owned by them grew to 41 percent.[171][172] Filipino entrepreneurs of Chinese ancestry are also responsible for generating 55 percent of overall Filipino private commercial business activity across the country.[173] In addition, Chinese-owned Filipino companies account for 66 percent of the sixty largest commercial entities.[174][175] In 2008, among the top ten wealthiest Filipinos, 6 to 7 were of Chinese ancestry with Henry Sy Sr. having topped the list with an estimated net worth US$14.4 billion.[176] In 2015, the top 4 wealthiest people in the Philippines (with 9 being pure-blooded Han Chinese in addition to 10 out of the top 15) were of Chinese ancestry.[177][142] In 2019, 15 of the 17 Filipino billionaires were of Chinese ancestry.[178]

Filipinos of Chinese ancestry exert a considerable influential foothold across the Filipino industrial manufacturing sector. With respect to delineating the parameters by industry distribution, Chinese-owned manufacturing establishments account for a third of the entirety of the Filipino industrial manufacturing sector.[119][164][179] The majority of Filipino industrial manufacturing establishments that produce the processing of coconut products, flour, food products, textiles, plastic products, footwear, glass, as well as heavy industry products such as metals, steel, industrial chemicals, paper products, paints, leatherwork, garments, sugar refining, timber processing, construction materials, food and beverages, rubber, plastics, semiconductors, and personal computers are controlled by Filipino entrepreneurs of Chinese ancestry.[11][119][180][181] In the secondary industry, 75 percent of the country's 2500 rice mills were Chinese-owned. Chinese Filipino entrepreneurs were also dominant in wood processing, and accounted for over 10 percent of the capital invested in the lumber industry and controlled 85 percent of it as well as accounting for 40 percent of the industry's annual output propagated through their extensive control of nearly all the sawmills throughout the country.[182] Emerging import-substituting light industries induced the active participation and ownership of Chinese entrepreneurs being involved in various several salt works in addition to a large number of small and medium-sized producers engaged in food processing as well as the production of leather and tobacco goods. The Chinese also hold enormous sway over the Filipino food processing industry with approximately 200 outlets being involved in this sector alone predominating the eventual export of their finished products to Hong Kong, Singapore, and Taiwan. More than 200 Chinese-owned companies are also involved in the production of paper, paper products, fertilizers, cosmetics, rubber products, and plastics.[183] By the early 1960s, the Chinese presence in the manufacturing sector became even more significant. Of the industrial manufacturing establishments that employed 10 or more workers, 35 percent were Chinese-owned and among 284 enterprises employing more than 100 workers, 37 percent were likewise Chinese-owned. Of the 163 domestic industrial manufacturing companies operating throughout the Philippines, 80 were Chinese-owned and included the manufacturing of coconut oil, food products, tobacco, textiles, plastic products, footwear, glass, and certain types of metals such as tubes and pipes, wire rods, nails, bolts, and containers.[184] In 1965, the Chinese controlled 32 percent of the country's top industrial manufacturing outlets.[185][186][187] Of the 259 industrial manufacturing establishments belonging to the top 1000 that operated throughout the entire country, the Chinese owned 33.6 percent of the top manufacturing companies as well as 43.2 percent of the top commercial manufacturing outlets in 1980.[164][188] By 1986, the Chinese controlled 45 percent of the country's top 120 domestic manufacturing companies.[119][189][190][191] These manufacturing establishments are mainly involved in the production of tobacco and cigarettes, soap and cosmetics, textiles and rubber footwear.[180]

Today, Filipinos of Chinese ancestry control all of the Philippines's largest and most lucrative department stores, supermarkets, and fast-food restaurants.

In 1940, Filipinos of Chinese ancestry were estimated to control 70 percent of the country's entire retail trade and 75 percent of the nation's rice mills.

Since the 1950s, Filipino entrepreneurs of Chinese ancestry have controlled the entirety of the Filipino retail industry.[208] Every small, medium, and large enterprise in the Filipino retail sector is now completely under Chinese hands as they have been at the forefront at pioneering the modern and contemporary development of the Philippines's retail sector.[209] From the 1970s onward, Filipino entrepreneurs of Chinese ancestry have re-established themselves as the dominant players in the Filipino retail industry with the community having achieved a collective corporate feat of presiding an estimated 8500 Chinese-owned retail and wholesale outlets that predominate across various metropolitan areas the country.[11][210] On a microscopic scale, the Hokkien community have a proclivity to run capital intensive businesses such as banks, commercial shipping lines, rice mills, dry goods, and general stores while the Cantonese gravitated towards hotels, restaurants, and laundromats.[211][207] Filipino entrepreneurs of Chinese ancestry control 35 percent to upwards to two-thirds of the domestic sales among the country's 67 largest commercial retail outlets.[212][213][214][215] By the 1980s, Filipino entrepreneurs of Chinese ancestry began to expand their business activities by venturing into large-scale retailing.

Chinese-owned Filipino retail outlet's today are among the single largest owners of department store chains in the Philippines with one prominent example being

From small trade cooperatives clustered by hometown pawnbrokers, Filipinos of Chinese ancestry would go on to establish and incorporate the largest financial services institutions in the country. Filipinos of Chinese ancestry have been the chief pioneering influence in the Filipino financial sector as they dominated the country's financial services domain and have had a presence in the country's banking industry since the early part of the 20th century. The two earliest Chinese-founded Filipino banks were

Filipinos of Chinese ancestry also wield enormous clout over the Philippines's real estate sector with much of the modern industry's grip being commercially grasped in their shrewdly enterprising and investment-savvy clutches. The line of revenue-generating business and income-producing investment opportunities that allowed the Chinese to expand their economic predominance into the Filipino real estate industry presented themselves occurred when the Chinese were finally conferred full-fledged Filipino citizenship during the

The Chinese also pioneered the Filipino shipping industry which eventually germinated into a major industry sector as a means of transporting goods cheaply and quickly between the islands. Filipino entrepreneurs of Chinese ancestry have remained dominant in the Philippines's maritime shipping and sea transport industry as it was one of the few efficient methods of transporting goods cheaply and quickly across the country, with the Philippines geographically being an archipelago, comprising more than 1000 islands and inlets.

As Filipino businesspeople of Chinese ancestry became more financially prosperous, they often coalesced their financial resources and pooled large amounts of seed capital together to forge joint business ventures with expatriate Mainland and Overseas Chinese businessmen and investors from all over the world. Like other Chinese-owned businesses operating throughout the Southeast Asian markets, Chinese-owned businesses in the Philippines often link up with Greater Chinese and other Overseas Chinese businesses and networks across the globe to focus on new business opportunities to collaborate and concentrate on. Common industry sectors of focus include real estate, engineering, textiles, consumer electronics, financial services, food, semiconductors, and chemicals.[257] Besides sharing a common ancestry, cultural, linguistic, and familial ties, many Filipino entrepreneurs and investors of Chinese ancestry are particular strong adherents of the Confucian paradigm of interpersonal relationships when doing business with each other, as the Chinese believed that the underlying source for entrepreneurial and investment success relied on the nurturing of personal relationships.[180] Moreover, Filipino businesses that are Chinese-owned form a part of the larger bamboo network, an umbrella business network of Overseas Chinese companies operating in the markets of Greater China and Southeast Asia that share common family, ethnic, linguistic, and cultural ties.[258][259] With the spectacular growth of varying success stories witnessed by a number of individual Chinese Filipino business tycoons and investors have allowed them to expand their traditional corporate activities beyond the Philippines to forge international partnerships with increasing numbers of expatriate Mainland and Overseas Chinese investors on a global scale.[260] Instead of quixotically diverting excess profits elsewhere, many Filipino businesspeople of Chinese ancestry are known for their penurious and parsimonious ways by eschewing improvident lavish extravagances and frivolous conspicuous consumption but instead adhere to the Chinese paradigm of being frugal by pragmatically, productively, and methodically reinvesting substantial surpluses of their business profits devoted for the purpose of commercial business expansion and performing the acquisition of cash flow producing and income-generating assets. A sizable percentage of the conglomerates managed by capable Filipino entrepreneurs and investors of Chinese ancestry that are armed with the necessary managerial capabilities, enterprising disposition, commercial expertise, entrepreneurial acumen, investment savvy, and visionary foresight were able to germinate from small budding enterprises to making headway into gargantuan corporate leviathans garnering widespread economic influence across the Philippines, Southeast Asia, and the global financial markets.[114] Such massive corporate expansions engendered the term "Chinoy", which is colloquially used in Filipino newspapers to denote Filipino individuals with a degree of Chinese ancestry who either speak a Chinese dialect or adhere to Chinese customs.

As Chinese economic might grew, much of the indigenous Filipino majority were gradually driven out and displaced into poorer land on the hills, on the outskirts of major Filipino cities, or into the mountains.[111] Disenchantment grew among the displaced indigenous Filipinos who felt they were unable compete with Chinese-owned businesses.[261] Underlying resentment and bitterness from the impoverished Filipino majority has been accumulating as there has been no existence of indigenous Filipino having any substantial business equity in the Philippines.[111] Decades of free market liberalization brought virtually no economic benefit to the indigenous Filipino majority but rather the opposite resulting a subjugated indigenous Filipino majority underclass, where the vast disproportion of indigeneous Filipinos still engage in rural peasantry, menial labor or domestic service and squatting.[104][111] The Filipino government has dealt with this wealth disparity by establishing socialist and communist dictatorships or authoritarian regimes while pursuing a systematic and ruthless affirmative action campaigns giving privileges to allow the indigenous Filipino majority to gain a more equitable economic footing during the 1950s and 1960s.[262][263] The rise of economic nationalism among the impoverished indigenous Filipino majority prompted by the Filipino government resulted in the passing of the Retail Trade Nationalization Law of 1954, where ethnic Chinese were barred and pressured to move out of the retail sector restricting engagement to Filipino citizens only.[263] In addition, the Chinese were prevented from owning land by restricting land ownership to Filipinos only. Other restrictions on Chinese economic activities included limiting Chinese involvement in the import-export trade while trying to increase the indigenous Filipino involvement to gain a proportionate presence. In 1960, the Rice and Corn Nationalization Law was passed restricting trading, milling, and warehousing of rice and corn only to Filipinos while barring Chinese involvement, in which they initially had a significant presence.[262][263][264][265] These policies ultimately backfired on the government as the laws had an overall negative impact on the government tax revenue which dropped significantly because the country's biggest source of taxpayers were Chinese, who eventually took their capital out of the country to invest elsewhere.[262][263] The increased economic clout held in the hands of the Chinese has triggered bitterness, suspicion, resentment, envy, insecurity, grievance, instability, ethnic hatred, and outright anti-Chinese hostility among the indigenous native Filipino majority towards the Chinese minority.[112] Such hostility has resulted in the kidnapping of hundreds of Chinese Filipinos by indigeneous Filipinos since the 1990s.[112] Many victims, often children are brutally murdered, even after a ransom is paid.[111][112] Numerous incidents of crimes such kidnap-for-ransom, extortion, and other forms of harassment were committed against the Chinese Filipino community starting from the early 1990s continues to this very day.[36][112] Thousands of displaced Filipino hill tribes and aborigines continue to live in satellite shantytowns on the outskirts of Manila in economic destitution where two-thirds of the country's indigenous Filipinos live on less than 2 dollars per day in extreme poverty.[111] Such animosity, antagonmism, bitterness, envy, grievance, hatred, insecurity, and resentment is ready at any moment to be catalyzed as a form of vengeneance by the downtrodden indigenous Filipino majority as many Chinese Filipinos are subject to kidnapping, vandalism, murder, and violence.[266] Anti-Chinese sentiment among the indigenous Filipino majority is deeply rooted in poverty but also feelings of resentment and exploitation are also exhibited among native and mestizo Filipinos blaming their socioeconomic failures on the Chinese.[112][266][267]

Future trends

Most of the younger generations of pure Chinese Filipinos are descendants of Chinese who migrated during the 1800s onward – this group retains much of Chinese culture, customs, and work ethic (though not necessarily language), whereas almost all Chinese mestizos are descendants of Chinese who migrated even before the Spanish colonial period and have been integrated and assimilated into the general Philippine society as a whole.

There are four trends that the Chinese Filipino would probably undertake within a generation or so:

- assimilation and integration, as in the case of Chinese Thais who eventually lost their genuine Chinese heritage and adopted Thai culture and language as their own

- separation, where the Chinese Filipino community can be clearly distinguished from the other ethnic groups in the Philippines; reminiscent of most Chinese Malaysians

- returning to the ancestral land, which is the current phenomenon of overseas Chinese returning to China

- emigration to North America and Australasia, as in the case of some Chinese Malaysians and many Chinese Vietnamese (Hoa people)

During the 1970s, Fr. Charles McCarthy, an expert in Philippine-Chinese relations, observed that "the peculiarly Chinese content of the Philippine-Chinese subculture is further diluted in succeeding generations" and he made a prediction that "the time will probably come and it may not be far off, when, in this sense, there will no more 'Chinese' in the Philippines". This view is still controversial however, with the constant adoption of new cultures by Filipinos contradicting this thought.

Integration and assimilation

Assimilation is defined as the adoption of the cultural norms of the dominant or host culture, while integration is defined as the adoption of the cultural norms of the dominant or host culture while maintaining their culture of origin.

As of the present day, due to the effects of globalization in the Philippines, there has been a marked tendency to assimilate to Filipino lifestyles influenced by the US, among ethnic Chinese. This is especially true for younger Chinese Filipino living in Metro Manila[268] who are gradually shifting to English as their preferred language, thus identifying more with Western culture, at the same time speaking Chinese among themselves. Similarly, as the cultural divide between Chinese Filipino and other Filipinos erode, there is a steady increase of intermarriages with native and mestizo Filipinos, with their children completely identifying with the Filipino culture and way of life. Assimilation is gradually taking place in the Philippines, albeit at a slower rate as compared to Thailand.[269]

On the other hand, the largest Chinese Filipino organization, the Kaisa Para Sa Kaunlaran openly espouses eventual integration but not assimilation of the Chinese Filipino with the rest of Philippine society and clamors for maintaining Chinese language education and traditions.

Meanwhile, the general Philippine public is largely neutral regarding the role of the Chinese Filipino in the Philippines, and many have embraced Chinese Filipino as fellow Filipino citizens and even encouraged them to assimilate and participate in the formation of the Philippines' destiny.

Separation

Separation is defined as the rejection of the dominant or host culture in favor of preserving their culture of origin, often characterized by the presence of ethnic enclaves.

The recent rapid economic growth of both China and Taiwan as well as the successful business acumen of Overseas Chinese have fueled among many Chinese Filipino a sense of pride through immersion and regaining interest in Chinese culture, customs, values and language while remaining in the Philippines.[citation needed]