Chlamydia

| Chlamydia | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Chlamydia infection |

burning with urination[1] | |

| Complications | Pain in the testicles, pelvic inflammatory disease, infertility, ectopic pregnancy[1][2] |

| Usual onset | Few weeks following exposure[1] |

| Causes | Chlamydia trachomatis spread by sexual intercourse or childbirth[3] |

| Diagnostic method | Urine or swab of the cervix, vagina, or urethra[2] |

| Prevention | Not having sex, condoms, sex with only one non–infected person[1] |

| Treatment | Antibiotics (azithromycin or doxycycline)[2] |

| Frequency | 4.2% (women), 2.7% (men)[4][5] |

| Deaths | ~200 (2015)[6] |

Chlamydia, or more specifically a chlamydia infection, is a

Chlamydia infections can occur in other areas besides the genitals, including the anus, eyes, throat, and lymph nodes. Repeated chlamydia infections of the eyes that go without treatment can result in

Chlamydia can be spread during

Prevention is by not having sex, the use of condoms, or having sex with only one other person, who is not infected.[1] Chlamydia can be cured by antibiotics with typically either azithromycin or doxycycline being used.[2] Erythromycin or azithromycin is recommended in babies and during pregnancy.[2] Sexual partners should also be treated, and infected people should be advised not to have sex for seven days and until symptom free.[2] Gonorrhea, syphilis, and HIV should be tested for in those who have been infected.[2] Following treatment people should be tested again after three months.[2]

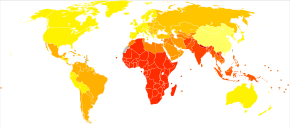

Chlamydia is one of the most common sexually transmitted infections, affecting about 4.2% of women and 2.7% of men worldwide.[4][5] In 2015, about 61 million new cases occurred globally.[11] In the United States about 1.4 million cases were reported in 2014.[3] Infections are most common among those between the ages of 15 and 25 and are more common in women than men.[2][3] In 2015 infections resulted in about 200 deaths.[6] The word chlamydia is from the Greek χλαμύδα, meaning 'cloak'.[12][13]

Signs and symptoms

Genital disease

Women

Chlamydial infection of the

Chlamydia is known as the "silent epidemic", as at least 70% of genital C. trachomatis infections in women (and 50% in men) are asymptomatic at the time of diagnosis,

For sexually active women who are not pregnant, screening is recommended in those under 25 and others at risk of infection.[16] Risk factors include a history of chlamydial or other sexually transmitted infection, new or multiple sexual partners, and inconsistent condom use.[17] Guidelines recommend all women attending for emergency contraceptive are offered chlamydia testing, with studies showing up to 9% of women aged <25 years had chlamydia.[18]

Men

In men, those with a chlamydial infection show symptoms of infectious inflammation of the urethra in about 50% of cases.[15] Symptoms that may occur include: a painful or burning sensation when urinating, an unusual discharge from the penis, testicular pain or swelling, or fever. If left untreated, chlamydia in men can spread to the testicles causing epididymitis, which in rare cases can lead to sterility if not treated.[15] Chlamydia is also a potential cause of prostatic inflammation in men, although the exact relevance in prostatitis is difficult to ascertain due to possible contamination from urethritis.[19]

Eye disease

Joints

Chlamydia may also cause reactive arthritis—the triad of arthritis, conjunctivitis and urethral inflammation—especially in young men. About 15,000 men develop reactive arthritis due to chlamydia infection each year in the U.S., and about 5,000 are permanently affected by it. It can occur in both sexes, though is more common in men.[citation needed]

Infants

As many as half of all infants born to mothers with chlamydia will be born with the disease. Chlamydia can affect infants by causing spontaneous abortion;

Other conditions

A different

Transmission

Chlamydia can be transmitted during vaginal, anal, oral, or manual sex or direct contact with infected tissue such as conjunctiva. Chlamydia can also be passed from an infected mother to her baby during vaginal childbirth.[27] It is assumed that the probability of becoming infected is proportionate to the number of bacteria one is exposed to.[30]

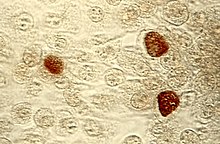

Pathophysiology

Chlamydiae have the ability to establish long-term associations with host cells. When an infected host cell is starved for various nutrients such as amino acids (for example, tryptophan),[31] iron, or vitamins, this has a negative consequence for Chlamydiae since the organism is dependent on the host cell for these nutrients. Long-term cohort studies indicate that approximately 50% of those infected clear within a year, 80% within two years, and 90% within three years.[32]

The starved chlamydiae enter a persistent growth state wherein they stop cell division and become morphologically aberrant by increasing in size.[33] Persistent organisms remain viable as they are capable of returning to a normal growth state once conditions in the host cell improve.[34]

There is debate as to whether persistence has relevance. Some believe that persistent chlamydiae are the cause of chronic chlamydial diseases. Some antibiotics such as

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of genital chlamydial infections evolved rapidly from the 1990s through 2006.

At present, the NAATs have regulatory approval only for testing urogenital specimens, although rapidly evolving research indicates that they may give reliable results on rectal specimens.

Because of improved test accuracy, ease of specimen management, convenience in specimen management, and ease of screening sexually active men and women, the NAATs have largely replaced culture, the historic gold standard for chlamydia diagnosis, and the non-amplified probe tests. The latter test is relatively insensitive, successfully detecting only 60–80% of infections in asymptomatic women, and often giving falsely-positive results. Culture remains useful in selected circumstances and is currently the only assay approved for testing non-genital specimens. Other methods also exist including: ligase chain reaction (LCR), direct fluorescent antibody resting, enzyme immunoassay, and cell culture.[39]

The swab sample for chlamydial infections does not show difference whether the sample was collected in home or in clinic in terms of numbers of patient treated. The implications in cured patients, reinfection, partner management, and safety are unknown.[40]

Rapid point-of-care tests are, as of 2020, not thought to be effective for diagnosing chlamydia in men of reproductive age and non-pregnant women because of high false-negative rates.[41]

Prevention

Prevention is by not having sex, the use of condoms, or having sex with only one other person, who is not infected.[1]

Screening

For sexually active women who are not pregnant, screening is recommended in those under 25 and others at risk of infection.

In the United Kingdom the National Health Service (NHS) aims to:

- Prevent and control chlamydia infection through early detection and treatment of asymptomatic infection;

- Reduce onward transmission to sexual partners;

- Prevent the consequences of untreated infection;

- Test at least 25 percent of the sexually active under 25 population annually.[43]

- Retest after treatment.[44]

Treatment

C. trachomatis infection can be effectively cured with antibiotics. Guidelines recommend azithromycin, doxycycline, erythromycin, levofloxacin or ofloxacin.[45] In men, doxycycline (100 mg twice a day for 7 days) is probably more effective than azithromycin (1 g single dose) but evidence for the relative effectiveness of antibiotics in women is very uncertain.[46] Agents recommended during pregnancy include erythromycin or amoxicillin.[2][47]

An option for treating sexual partners of those with chlamydia or

Following treatment people should be tested again after three months to check for reinfection.

Epidemiology

Globally, as of 2015, sexually transmitted chlamydia affects approximately 61 million people.[11] It is more common in women (3.8%) than men (2.5%).[51] In 2015 it resulted in about 200 deaths.[6]

In the United States about 1.6 million cases were reported in 2016.[52] The CDC estimates that if one includes unreported cases there are about 2.9 million each year.[52] It affects around 2% of young people.[53] Chlamydial infection is the most common bacterial sexually transmitted infection in the UK.[54]

Chlamydia causes more than 250,000 cases of epididymitis in the U.S. each year. Chlamydia causes 250,000 to 500,000 cases of PID every year in the United States. Women infected with chlamydia are up to five times more likely to become infected with HIV, if exposed.[27]

See also

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l "Chlamydia – CDC Fact Sheet". CDC. May 19, 2016. Archived from the original on 11 June 2016. Retrieved 10 June 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o "2015 Sexually Transmitted Diseases Treatment Guidelines". CDC. June 4, 2015. Archived from the original on 11 June 2016. Retrieved 10 June 2016.

- ^ a b c d "2014 Sexually Transmitted Diseases Surveillance Chlamydia". November 17, 2015. Archived from the original on 10 June 2016. Retrieved 10 June 2016.

- ^ PMID 26646541.

- ^ a b "Sexually transmitted infections (STIs) Fact sheet N°110". who.int. December 2015. Archived from the original on 25 November 2014. Retrieved 10 June 2016.

- ^ PMID 27733281.

- ^ Shors T (2018). Krasner's Microbial Challenge. p. 366.

- ^ a b "CDC – Trachoma, Hygiene-related Diseases, Healthy Water". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. December 28, 2009. Archived from the original on September 5, 2015. Retrieved 2015-07-24.

- ISBN 978-1-35118-825-8. Retrieved July 11, 2023.

- ISBN 9780323292412. Archivedfrom the original on 2017-09-10.

- ^ PMID 27733282.

- ISBN 9780199571123. Archivedfrom the original on 10 September 2017. Retrieved 10 June 2016.

- PMID 12835422.

The term was coined based on the incorrect conclusion that Chlamydia are intracellular protozoan pathogens that appear to cloak the nucleus of infected cells.

- ^ PMID 28835360.

- ^ a b c NHS Chlamydia page Archived 2013-01-16 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ PMID 18386598. Archived from the originalon 2021-08-28. Retrieved 2008-03-17.

- ^ from the original on 2008-03-03.

- PMID 25624285.

- S2CID 34481915.

- ^ )

- PMID 7704921. Archived from the original(PDF) on 2008-06-25.

- PMID 15640920.

- S2CID 208789262.

- ^ World Health Organization. Trachoma Archived 2012-10-21 at the Wayback Machine. Accessed March 17, 2008.

- S2CID 45018412.

- ^ "Trachoma". www.who.int. Retrieved 2023-06-27.

- ^ a b c "STD Facts – Chlamydia". Center For Disease Control. December 16, 2014. Archived from the original on July 14, 2015. Retrieved 2015-07-24.

- ISBN 978-0-19-539134-3, retrieved 15 December 2022

- PMID 16410585.

- PMID 17521595.

- PMID 17724071.

- PMID 17717486.

- PMID 16338585.

- ^ Kushwaha AK (2020-07-26). Textbook of Microbiology. Dr. A.K KUSHWAHA.

- PMID 29269129.

- PMID 27726004.

- PMID 15243057.

- ^ PMID 20338058.

- ^ "Recommendations for the Laboratory-Based Detection of Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae — 2014". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Archived from the original on 2016-06-27. Retrieved 2016-06-12.

- PMID 26418128.

- PMID 31995238.

- PMID 27623210.

- ^ "National Chlamydia Screening Programme Data tables". www.chlamydiascreening.nhs.uk. Archived from the original on 2009-05-04. Retrieved 2009-08-28.

- PMID 25759476.

Strategies for improved follow up care include the use of text messages and emails from those who provided treatment.

- ISBN 978-1-930808-65-2.

- PMID 30682211.

- from the original on November 27, 2011. Retrieved 2010-10-30.

- ^ Expedited Partner Therapy in the Management of Sexually Transmitted Diseases (2 February 2006) Archived 29 July 2017 at the Wayback Machine U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Public Health Service. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention National Center for HIV, STD, and TB Prevention

- PMID 22470526.

- ^ "WHO Disease and injury country estimates". World Health Organization. 2004. Archived from the original on 2009-11-11. Retrieved Nov 11, 2009.

- PMID 23245607.

- ^ a b "Detailed STD Facts – Chlamydia". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 20 September 2017. Retrieved 14 January 2018.

- PMID 25254560.

- ^ "Chlamydia". UK Health Protection Agency. Archived from the original on 13 September 2012. Retrieved 31 August 2012.

External links

- WHO fact sheet on chlamydia

- Chlamydia at Curlie

- Chlamydia Fact Sheet from the CDC