Cholecalciferol

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation | /ˌkoʊləkælˈsɪfərɒl/ |

| Other names | vitamin D3, calciol, activated 7-dehydrocholesterol |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Professional Drug Facts |

| License data | |

By mouth, intramuscular | |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Identifiers | |

| |

JSmol) | |

| Melting point | 83 to 86 °C (181 to 187 °F) |

| Boiling point | 496.4 °C (925.5 °F) |

| Solubility in water | Practically insoluble in water, freely soluble in ethanol, methanol and some other organic solvents. Slightly soluble in vegetable oils. |

| |

| |

Cholecalciferol, also known as vitamin D3 and colecalciferol, is a type of vitamin D that is made by the skin when exposed to sunlight; it is found in some foods and can be taken as a dietary supplement.[3]

Cholecalciferol is made in the skin following UVB light exposure.[4] It is converted in the liver to calcifediol (25-hydroxyvitamin D) which is then converted in the kidney to calcitriol (1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D).[4] One of its actions is to increase calcium uptake by the intestines.[5] It is found in food such as some fish, beef liver, eggs, and cheese.[6][7] Plants, cow milk, fruit juice, yogurt, and margarine also may have cholecalciferol added to them in some countries, including the United States.[6][7]

Cholecalciferol can be taken as an oral dietary supplement to prevent

Cholecalciferol was first described in 1936.

Medical uses

Cholecalciferol appears to stimulate the body's

Vitamin D deficiency

Cholecalciferol is a form of vitamin D which is naturally synthesized in skin and functions as a pro-hormone, being converted to calcitriol. This is important for maintaining calcium levels and promoting bone health and development.[4] As a medication, cholecalciferol may be taken as a dietary supplement to prevent or to treat vitamin D deficiency. One gram is 40,000,000 (40x106) IU, equivalently 1 IU is 0.025 μg or 25 ng. Dietary reference intake values for vitamin D (ergocalciferol which is D2 and/or cholecalciferol which is D3) have been established and recommendations vary depending on the country:

- In the US: 15 μg/d (600 IU per day) for all individuals (males, females, pregnant/lactating women) between the ages of 1 and 70 years old, inclusive. For all individuals older than 70 years, 20 μg/d (800 IU per day) is recommended.[20]

- In the EU: 15 μg/d (600 IU per day) for all people older than 1 year and 10 μg/d (400 IU per day) for infants aged 7–11 months, assuming minimal cutaneous vitamin D synthesis.[21]

- In the UK: a ‘Safe Intake’ (SI) of 8.5-10 μg/day (30-400 IU per day) for infants < 1 year (including exclusively breastfed infants) and a SI of 10 μg/day (400 IU per day) for children aged 1 to <4 years; for all other population groups aged 4 years and more (including pregnant/lactating women) a Reference Nutrient Intake (RNI) of 10 μg/day (400 IU per day).[22]

Low levels of vitamin D are more commonly found in individuals living in northern latitudes, or with other reasons for a lack of regular sun exposure, including being housebound, frail, elderly, obese, having darker skin, or wearing clothes that cover most of the skin.[23][24] Supplements are recommended for these groups of people.[24]

The

There are conflicting reports concerning the relative effectiveness of cholecalciferol (D3) versus ergocalciferol (D2), with some studies suggesting less efficacy of D2, and others showing no difference. There are differences in absorption, binding and inactivation of the two forms, with evidence usually favoring cholecalciferol in raising levels in blood, although more research is needed.[27]

A much less common use of cholecalciferol therapy in rickets utilizes a single large dose and has been called stoss therapy.[28][29][30] Treatment is given either orally or by intramuscular injection of 300,000 IU (7,500 μg) to 500,000 IU (12,500 μg = 12.5 mg), in a single dose, or sometimes in two to four divided doses. There are concerns about the safety of such large doses.[30]

Low circulating vitamin D levels have been associated with lower total testosterone levels in males. Vitamin D supplementation could potentially improve total testosterone concentration, although more research is needed.[31]

Other diseases

A meta-analysis of 2007 concluded that daily intake of 1000 to 2000 IU per day of vitamin D3 could reduce the incidence of colorectal cancer with minimal risk.[32] Also a 2008 study published in Cancer Research has shown the addition of vitamin D3 (along with calcium) to the diet of some mice fed a regimen similar in nutritional content to a new Western diet with 1000 IU cholecalciferol per day prevented colon cancer development.[33] In humans, with 400 IU daily, there was no effect of cholecalciferol supplements on the risk of colorectal cancer.[34]

Supplements are not recommended for prevention of cancer as any effects of cholecalciferol are very small.[35] Although correlations exist between low levels of blood serum cholecalciferol and higher rates of various cancers, multiple sclerosis, tuberculosis, heart disease, and diabetes,[36] the consensus is that supplementing levels is not beneficial.[37] It is thought that tuberculosis may result in lower levels.[38] It, however, is not entirely clear how the two are related.[39]

Biochemistry

Structure

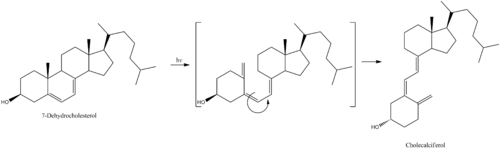

Cholecalciferol is one of the five forms of vitamin D.[40] Cholecalciferol is a secosteroid, that is, a steroid molecule with one ring open.[41]

Mechanism of action

By itself cholecalciferol is inactive. It is converted to its active form by two

Biosynthesis

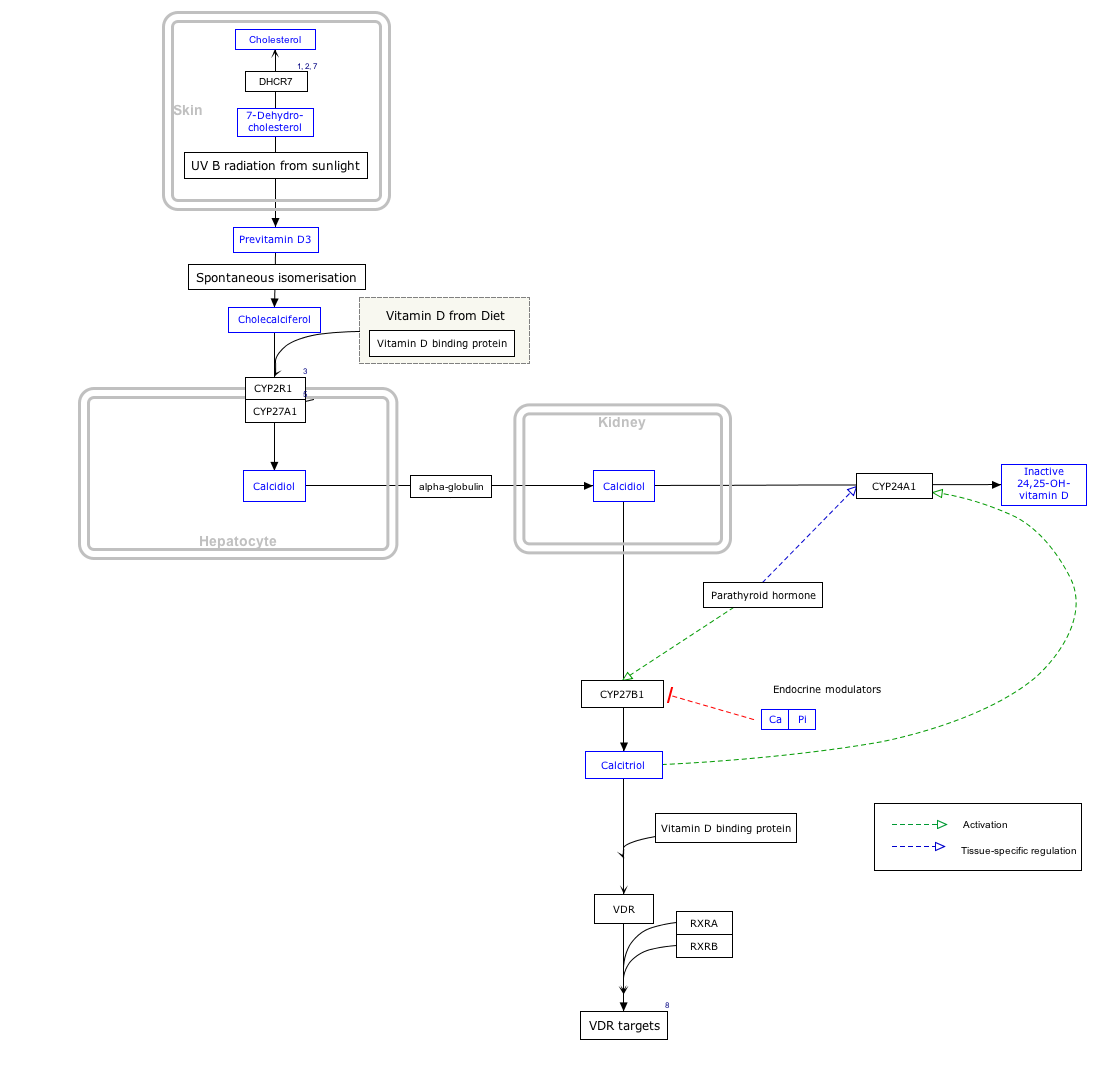

Click on icon in lower right corner to open.

Click on genes, proteins and metabolites below to link to respective articles. [§ 1]

- ^ The interactive pathway map can be edited at WikiPathways: "VitaminDSynthesis_WP1531".

The active UVB wavelengths are present in sunlight, and sufficient amounts of cholecalciferol can be produced with moderate exposure of the skin, depending on the strength of the sun.[42] Time of day, season, latitude, and altitude affect the strength of the sun, and pollution, cloud cover or glass all reduce the amount of UVB exposure. Exposure of face, arms and legs, averaging 5–30 minutes twice per week, may be sufficient, but the darker the skin, and the weaker the sunlight, the more minutes of exposure are needed. Vitamin D overdose is impossible from UV exposure; the skin reaches an equilibrium where the vitamin degrades as fast as it is created.[42]

Cholecalciferol can be produced in skin from the light emitted by the UV lamps in

Whether cholecalciferol and all forms of vitamin D are by definition "

The three steps in the synthesis and activation of vitamin D3 are regulated as follows:

- Cholecalciferol is synthesized in the skin from 7-dehydrocholesterol under the action of ultraviolet B (UVB) light. It reaches an equilibrium after several minutes depending on the intensity of the UVB in the sunlight – determined by latitude, season, cloud cover, and altitude – and the age and degree of pigmentation of the skin.

- Hydroxylation in the endoplasmic reticulum of liver hepatocytes of cholecalciferol to calcifediol (25-hydroxycholecalciferol) by 25-hydroxylase is loosely regulated, if at all, and blood levels of this molecule largely reflect the amount of cholecalciferol produced in the skin combined with any vitamin D2 or D3 ingested.

- Hydroxylation in the kidneys of calcifediol to calcitriol by 1-alpha-hydroxylase is tightly regulated: it is stimulated by parathyroid hormone and serves as the major control point in the production of the active circulating hormone calcitriol (1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3).[4]

Industrial production

Cholecalciferol is produced industrially for use in

Cholecalciferol is also produced industrially for use in vitamin supplements from lichens, which is suitable for vegans.[46][47]

Stability

Cholecalciferol is very sensitive to UV radiation and will rapidly, but reversibly, break down to form supra-sterols, which can further irreversibly convert to ergosterol.[citation needed]

Pesticide

Rodents are somewhat more susceptible to high doses than other species, and cholecalciferol has been used in poison bait for the control of these pests.[48][18]

The mechanism of high dose cholecalciferol is that it can produce "

In New Zealand, possums have become a significant pest animal. For possum control, cholecalciferol has been used as the active ingredient in lethal baits.[50] The LD50 is 16.8 mg/kg, but only 9.8 mg/kg if calcium carbonate is added to the bait.[51][52] Kidneys and heart are target organs.[53] LD50 of 4.4 mg/kg has been reported in rabbits, with lethality to almost all rabbits ingesting doses greater than 15 mg/kg.[54] Toxicity has been reported across a wide range of cholecalciferol dosages, with LD50 as high as 88 mg/kg or LDLo as low as 2 mg/kg reported for dogs.[55]

Researchers have reported that the compound is less toxic to non-target species than earlier generations of anticoagulant rodenticides (

See also

- Hypervitaminosis D, Vitamin D poisoning

- Ergocalciferol, vitamin D2

- 25-Hydroxyvitamin D 1-alpha-hydroxylase, a kidney enzyme that converts calcifediol to calcitriol

References

- ^ "Health product highlights 2021: Annexes of products approved in 2021". Health Canada. 3 August 2022. Retrieved 25 March 2024.

- ^ "Regulatory Decision Summary for Vitamin D3 Oral Solution". Health Canada. 5 February 2021. Retrieved 25 March 2024.

- ISBN 9780123918840. Archivedfrom the original on 30 December 2016. Retrieved 29 December 2016.

- ^ PMID 18689389.

- ^ a b c "Cholecalciferol (Professional Patient Advice) - Drugs.com". www.drugs.com. Archived from the original on 30 December 2016. Retrieved 29 December 2016.

- ^ a b "Office of Dietary Supplements - Vitamin D". ods.od.nih.gov. 11 February 2016. Archived from the original on 31 December 2016. Retrieved 30 December 2016.

- ^ S2CID 58721779.

- ISBN 9780857111562.

- ^ ISBN 9789241547659.

- ^ ISBN 9781284057560.

- ^ a b "Aviticol 1 000 IU Capsules - Summary of Product Characteristics (SPC) - (eMC)". www.medicines.org.uk. Archived from the original on 30 December 2016. Retrieved 29 December 2016.

- PMID 10232622.

- ISBN 978-3-527-60749-5. Archivedfrom the original on 30 December 2016. Retrieved 29 December 2016.

- hdl:10665/325771. WHO/MVP/EMP/IAU/2019.06. License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- ^ "The Top 300 of 2021". ClinCalc. Retrieved 14 January 2024.

- ^ "Cholecalciferol - Drug Usage Statistics". ClinCalc. Retrieved 14 January 2024.

- ^ a b c d Khan SA, Schell MM (November 2014). "Merck Veterinary Manual - Rodenticide Poisoning: Introduction". Retrieved 10 October 2021.

Incidence of vitamin D3 toxicosis in animals is relatively less than that of anticoagulant and bromethalin toxicosis. Relay toxicosis from vitamin D3 has not been documented.

- ^ a b Rizor SE, Arjo WM, Bulkin S, Nolte DL. Efficacy of Cholecalciferol Baits for Pocket Gopher Control and Possible Effects on Non-Target Rodents in Pacific Northwest Forests. Vertebrate Pest Conference (2006). USDA. Archived from the original on 14 September 2012. Retrieved 27 August 2019.

0.15% cholecalciferol bait appears to have application for pocket gopher control.' Cholecalciferol can be a single high-dose toxicant or a cumulative multiple low-dose toxicant.

- ^ Haridy R (28 February 2022). "One type of vitamin D found to boost immune system, another may hinder it". New Atlas. Retrieved 7 April 2022.

- ^ DRIs for Calcium and Vitamin D Archived 24 December 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Dietary reference values for vitamin D | EFSA". 28 October 2016.

- ^ "Joint explanatory note by the European Food Safety Authority and the UK Scientific Advisory Committee on Nutrition regarding dietary reference values for vitamin D" (PDF).

- S2CID 52858668.

- ^ a b "Vitamins and minerals – Vitamin D". National Health Service. 3 August 2020. Retrieved 15 November 2020.

- ^ PMID 10232622.

- PMID 20139241.

- PMID 22552031.

- PMID 8071764.

- PMID 27550890.

- ^ S2CID 40611968.

- S2CID 84841517.

- PMID 17296473.

- PMID 18829535.

- S2CID 20826870.

- PMID 24414552.

- PMID 16380576.

- PMID 21118827.

- PMID 30170465.

- PMID 26333888.

- ^ "cholecalciferol" at Dorland's Medical Dictionary

- ^ "About Vitamin D". University of California, Riverside. November 2011. Archived from the original on 16 October 2017. Retrieved 15 October 2017.

- ^ PMID 24494042.

- S2CID 23011680.

- .

- ^ Vitamin D3 Story. Archived 22 January 2012 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 8 April 2012.

- ^ "Vitashine Vegan Vitamin D3 Supplements". Archived from the original on 4 March 2013. Retrieved 15 March 2013.

- from the original on 28 October 2012.

- ^ a b CHOLECALCIFEROL: A UNIQUE TOXICANT FOR RODENT CONTROL. Proceedings of the Eleventh Vertebrate Pest Conference (1984). University of Nebraska Lincoln. March 1984. Archived from the original on 27 August 2019. Retrieved 27 August 2019.

Cholecalciferol is an acute (single-feeding) and/or chronic (multiple-feeding) rodenticide toxicant with unique activity for controlling commensal rodents including anticoagulant-resistant rats. Cholecalciferol differs from conventional acute rodenticides in that no bait shyness is associated with consumption and time to death is delayed, with first dead rodents appearing 3-4 days after treatment.

- PMID 9771340.

We investigated the effect of oral high-dose cholecalciferol on plasma and adipose tissue cholecalciferol and its subsequent release, and on plasma 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25(OH)D). ... We conclude that orally-administered cholecalciferol rapidly accumulates in adipose tissue and that it is very slowly released while there is energy balance.

- ^ "Pestoff DECAL Possum Bait - Rentokil Initial Safety Data Sheets" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 January 2021. Retrieved 10 May 2020.

- S2CID 83765759.

- .

- ^ "Kiwicare Material Safety Data Sheet" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 February 2013.

- ^ R. J. Henderson and C. T. Eason (2000), Acute toxicity of cholecalciferol and gliftor baits to the European rabbit, Oryctolagus cuniculus, Wildlife Research 27(3) 297-300.

- ^ Michael E.Peterson & Kerstin Fluegeman, Cholecalciferol (Topic Review), Topics in Companion Animal Medicine, Volume 28, Issue 1, February 2013, Pages 24-27.

- ISSN 0367-6722.

Use of cholecalciferol as a rodenticide in bait lowered the risk of secondary poisoning and minimized the toxicity of non-target species