Chondrichthyes

| Cartilaginous fishes | |

|---|---|

| |

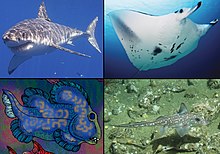

| Example of cartilaginous fishes: Elasmobranchii at the top of the image and Holocephali at the bottom of the image. | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Subphylum: | Vertebrata |

| Infraphylum: | Gnathostomata |

| Clade: | Eugnathostomata |

| Class: | Chondrichthyes Huxley, 1880 |

| Living subclasses and orders | |

| |

Chondrichthyes (

The class is divided into two subclasses: Elasmobranchii (sharks, rays, skates and sawfish) and Holocephali (chimaeras, sometimes called ghost sharks, which are sometimes separated into their own class). Extant Chondrichthyes range in size from the 10 cm (3.9 in) finless sleeper ray to the over 10 m (33 ft) whale shark.

Anatomy

Skeleton

The skeleton is cartilaginous. The notochord is gradually replaced by a vertebral column during development, except in Holocephali, where the notochord stays intact. In some deepwater sharks, the column is reduced.[9]

As they do not have bone marrow, red blood cells are produced in the spleen and the epigonal organ (special tissue around the gonads, which is also thought to play a role in the immune system). They are also produced in the Leydig's organ, which is only found in certain cartilaginous fishes. The subclass Holocephali, which is a very specialized group, lacks both the Leydig's and epigonal organs.

Appendages

Apart from

Originally, the pectoral and pelvic girdles, which do not contain any dermal elements, did not connect. In later forms, each pair of fins became ventrally connected in the middle when scapulocoracoid and puboischiadic bars evolved. In rays, the pectoral fins are connected to the head and are very flexible.

One of the primary characteristics present in most sharks is the heterocercal tail, which aids in locomotion.[10]

Body covering

Chondrichthyans have tooth-like scales called

It is assumed that their oral teeth evolved from dermal denticles that migrated into the mouth, but it could be the other way around, as the

The old

Respiratory system

All chondrichthyans breathe through five to seven pairs of gills, depending on the species. In general, pelagic species must keep swimming to keep oxygenated water moving through their gills, whilst demersal species can actively pump water in through their spiracles and out through their gills. However, this is only a general rule and many species differ.

A spiracle is a small hole found behind each eye. These can be tiny and circular, such as found on the nurse shark (Ginglymostoma cirratum), to extended and slit-like, such as found on the wobbegongs (Orectolobidae). Many larger, pelagic species, such as the mackerel sharks (Lamnidae) and the thresher sharks (Alopiidae), no longer possess them.

Nervous system

In chondrichthyans, the nervous system is composed of a small brain, 8–10 pairs of cranial nerves, and a spinal cord with spinal nerves.

Immune system

Like all other jawed vertebrates, members of Chondrichthyes have an adaptive immune system.[13]

Reproduction

Fertilization is internal. Development is usually live birth (

Capture-induced premature birth and abortion (collectively called capture-induced parturition) occurs frequently in sharks/rays when fished.[14] Capture-induced parturition is often mistaken for natural birth by recreational fishers and is rarely considered in commercial fisheries management despite being shown to occur in at least 12% of live bearing sharks and rays (88 species to date).[14]

Classification

The class Chondrichthyes has two subclasses: the subclass

Subclasses of cartilaginous fishes

| ||

|---|---|---|

| Elasmobranchii | Sharks

|

temperate waters.[15]

|

| Holocephali | Chimaeras

|

Callorhynchus ). Today, they preserve some features of elasmobranch life in Paleaozoic times, though in other respects they are aberrant. They live close to the bottom and feed on molluscs and other invertebrates. The tail is long and thin and they move by sweeping movements of the large pectoral fins. There is an erectile spine in front of the dorsal fin, sometimes poisonous. There is no stomach (that is, the gut is simplified and the 'stomach' is merged with the intestine), and the mouth is a small aperture surrounded by lips, giving the head a parrot-like appearance.

The fossil record of the Holocephali starts in the Devonian period. The record is extensive, but most fossils are teeth, and the body forms of numerous species are not known, or at best poorly understood. |

| Extant orders of cartilaginous fishes | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group | Order | Image | Common name | Authority | Families | Genera | Species | Note | ||||

| Total | ||||||||||||

Galean

sharks |

Carcharhiniformes |

|

ground

sharks |

Compagno, 1977 | 8 | 51 | >270 | 7 | 10 | 21 | ||

| Heterodontiformes |

|

bullhead

sharks |

L. S. Berg, 1940 | 1 | 1 | 9 | ||||||

| Lamniformes |

|

mackerel

sharks |

L. S. Berg, 1958 | 7 +2 extinct |

10 | 16 | 10 | |||||

Orectolobiformes

|

|

carpet

sharks |

Applegate, 1972 | 7 | 13 | 43 | 7 | |||||

| Squalomorph sharks |

Hexanchiformes |

|

frilled and cow sharks |

de Buen , 1926

|

2 +3 extinct |

4 +11 extinct |

7 +33 extinct |

|||||

Pristiophoriformes

|

sawsharks

|

L. S. Berg, 1958 | 1 | 2 | 6 | |||||||

| Squaliformes |

|

dogfish

sharks |

Goodrich, 1909 | 7 | 23 | 126 | 1 | 6 | ||||

| Squatiniformes |

|

angel

sharks |

Buen , 1926

|

1 | 1 | 24 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |||

| Rays | Myliobatiformes |

|

stingrays and relatives |

Compagno , 1973

|

10 | 29 | 223 | 1 | 16 | 33 | ||

| Rhinopristiformes |

|

sawfishes

|

1 | 2 | 5–7 | 5–7 | ||||||

| Rajiformes |

|

skates and guitarfishes |

L. S. Berg, 1940 | 5 | 36 | >270 | 4 | 12 | 26 | |||

Torpediniformes

|

|

electric

rays |

de Buen , 1926

|

2 | 12 | 69 | 2 | 9 | ||||

| Holocephali | Chimaeriformes

|

|

chimaera | Obruchev, 1953 | 3 +2 extinct |

6 +3 extinct |

39 +17 extinct |

|||||

| Taxonomy according to Leonard Compagno, 2005[16] with additions from [17] |

|---|

* position uncertain |

Evolution

Cartilaginous fish are considered to have evolved from

The earliest unequivocal fossils of acanthodian-grade cartilaginous fishes are Qianodus and Fanjingshania from the early Silurian (Aeronian) of Guizhou, China around 439 million years ago, which are also the oldest unambiguous remains of any jawed vertebrates.[24][25] Shenacanthus vermiformis, which lived 436 million years ago, had thoracic armour plates resembling those of placoderms.[26]

By the start of the Early Devonian, 419 million years ago,

| Extinct orders of cartilaginous fishes | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group | Order | Image | Common name | Authority | Families | Genera | Species | Note | |

| Holocephali | †Orodontiformes |

|

|||||||

| †Petalodontiformes |

|

Petalodonts | Zangerl, 1981 | 4 | Members of the holocephali, some genera resembled parrot fish, but some members of the Janassidae resembled skates. | ||||

| †Helodontiformes | |||||||||

| †Iniopterygiformes |

|

Members of the holocephali that resembled flying fish, are often characterized by large eyes, large upturned pectoral fins, and club-like tails. | |||||||

| †Debeeriiformes | |||||||||

†Symmoriida

|

|

Symmoriids | Zangerl, 1981 (sensu Maisey, 2007) | 4 | Members of the holocephali, they were heavily sexually dimorphic.[27]

| ||||

| †Eugeneodontida |

|

Eugeneodonts | Eugeneodontida

Zangerl, 1981 |

4 | Members of the holocephali, they are characterized by large tooth whorls in their jaws.[28] | ||||

| †Psammodonti- formes |

Position uncertain | ||||||||

| †Copodontiformes | |||||||||

†Squalorajiformes

|

|||||||||

| †Chondrenchelyi- formes |

|

||||||||

| †Menaspiformes |

|

||||||||

| †Cochliodontiformes | |||||||||

| Squalomorph sharks |

†Protospinaci- formes |

||||||||

| Other | †Squatinactiformes

|

|

Cappetta et al., 1993 | 1 | 1 | ||||

†Protacrodonti-

formes |

|||||||||

†Cladoselachi-

formes |

|

Dean, 1894 | 1 | 2 | Holocephalans, and potential members of the symmoriida. | ||||

†Xenacanthiformes

|

|

Xenacanths | Glikman, 1964 | 4 | Eel-like elasmobranchs that were some of the top freshwater predators of the late Paleozoic. | ||||

| †Ctenacanthi- formes |

|

Ctenacanths | Glikman, 1964 | 2 | Shark-like elasmobranchs characterized by their robust heads and large dorsal fin spines. | ||||

| †Hybodontiformes |

|

Hybodonts | Patterson, 1966 | 5 | Shark-like elasmobranchs distinguished by their conical tooth shape, and the presence of a spine on each of their two dorsal fins. | ||||

Taxonomy

SubphylumVertebrata└─Infraphylum Gnathostomata ├─Placodermi— extinct (armored gnathostomes) └Eugnathostomata(true jawed vertebrates) ├─Acanthodii (stem cartilaginous fish) └─Chondrichthyes (true cartilaginous fish) ├─Holocephali (chimaeras + several extinct clades) └Elasmobranchii (shark and rays) ├─Selachii(true sharks) └─Batoidea (rays and relatives)

- Note: Lines show evolutionary relationships.

See also

- List of cartilaginous fish

- Cartilaginous versus bony fishes

- Largest cartilaginous fishes

- Threatened rays

- Threatened sharks

- Placodermi

References

- ^ "Mazon Monday #19: Species Spotlight: Bandringa rayi #MazonCreek #fossils #MazonMonday #shark". Earth Science Club of Northern Illinois - ESCONI. Retrieved 4 October 2020.

- ^ "Bear Gulch - Delphyodontos dacriformes". Fossil Fishes of Bear Gulch. Archived from the original on 25 February 2015. Retrieved 15 May 2019.

- ^ Mutter, R.J.; Neuman, A.G. "An enigmatic chondrichthyan with Paleozoic affinities from the Lower Triassic of western Canada". Acta Palaeontologica Polonica. 51 (2): 271–282.

- ^ "Fossilworks: Acanthorhachis". fossilworks.org. Retrieved 17 December 2021.

- ISBN 978-3-89937-269-4, retrieved 30 November 2023

- .

- ^ Anderson, M. Eric; Long, John A.; Gess, Robert W.; Hiller, Norton (1999). "An unusual new fossil shark (Pisces: Chondrichthyes) from the Late Devonian of South Africa". Records of the Western Australian Museum. 57: 151–156.

- ISSN 1464-343X.

- ISBN 9789251045435– via Google Books.

- PMID 12124362.

- S2CID 207717002.

- PMID 26776480.

- PMID 19997068.

- ^ S2CID 90834034. Archived from the originalon 23 February 2019. Retrieved 18 January 2019.

- ASIN B000J0D9X6.

- ISBN 9780691120720.

- ^ Haaramo, Mikko. Chondrichthyes – Sharks, Rays and Chimaeras. Retrieved 22 October 2013.

- S2CID 4462506.

- doi:10.26879/601.

- (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022.

- S2CID 140675923.

- .

- PMID 27350896.

- S2CID 252570103.

- S2CID 252569771.

- S2CID 252569910.

- S2CID 4455946.

- PMID 23445952.