Christianity and Islam

| Part of a series on |

| Christianity |

|---|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Islam |

|---|

|

| Islam and other religions |

|---|

| Abrahamic religions |

| Other religions |

| Islam and... |

Christianity and Islam are the two largest religions in the world, with 2.8 billion and 1.9 billion adherents, respectively.

Muslims view Christians to be

Like Christianity, Islam considers Jesus to be the al-Masih (Arabic for Messiah) who was sent to guide the Banī Isrā'īl (Arabic for Children of Israel) with a new revelation: al-Injīl (Arabic for "the Gospel").[6][7][8] But while belief in Jesus is a fundamental tenet of both, a critical distinction far more central to most Christian faiths is that Jesus is the incarnated God, specifically, one of the hypostases of the Triune God, God the Son.

While Christianity and Islam hold their recollections of Jesus's teachings as gospel and share narratives from the first five books of the Old Testament (the Hebrew Bible), the sacred text of Christianity also includes the later additions to the Bible while the primary sacred text of Islam instead is the Quran. Muslims believe that al-Injīl was distorted or altered to form the Christian New Testament. Christians, on the contrary, do not have a univocal understanding of the Quran, though most believe that it is fabricated or apocryphal work. There are similarities in both texts, such as accounts of the life and works of Jesus and the virgin birth of Jesus through Mary; yet still, some Biblical and Quranic accounts of these events differ.

Similarities and differences

In the Islamic tradition, Christians, as well as Jews, are believed to worship the same God that Muslims worship.

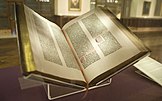

Scriptures

The Christian Bible is made up of the Old Testament and the New Testament. The Old Testament was written over a period of two millennia prior to the birth of Christ. The New Testament was written in the decades following the death of Christ. Historically, Christians universally believed that the entire Bible was the divinely inspired Word of God. However, the rise of harsher criticism during the Enlightenment has led to a diversity of views concerning the authority and inerrancy of the Bible in different denominations. Christians consider the Quran to be a non-divine set of texts.

The Quran dates from the early 7th century, or decades thereafter. Muslims believe it was revealed to Muhammad, gradually over a period of approximately 23 years, beginning on 22 December 609,

Jesus

Muslims and Christians both believe that Jesus was born to

Christianity and Islam also differ in their fundamental views related to the

Both Christians and Muslims believe in the Second Coming of Jesus. Christianity does not state where will Jesus return, while the Hadith in Islam states that Jesus will return at a white minaret at the east of

Muhammad

Muslims believe that Muhammad was a prophet, who received revelations (Quran) by God through the angel Gabriel (Jibril),[23][24] gradually over a period of approximately 23 years, beginning on 22 December 609,[25] when Muhammad was 40, and concluding in 632, the year of his death.[26][14][15] Muslims regard the Quran as the most important miracle of Muhammad, a proof of his prophethood.[27]

Muslims revere Muhammad as the embodiment of the perfect believer and take his actions and sayings as a model of ideal conduct. Unlike Jesus, who Christians believe was God's son, Muhammad was a mortal, albeit with extraordinary qualities. Today many Muslims believe that it is wrong to represent Muhammad, but this was not always the case. At various times and places pious Muslims represented Muhammad although they never worshiped these images.[28]

During the lifetime of Muhammad, he had many

God

In Christianity, the most common name of God is

The Holy Spirit

Christians and Muslims have differing views about the Holy Spirit. Most Christians believe that the Holy Spirit is God, and the third member of the Trinity. In Islam, the Holy Spirit is generally believed to be the angel Gabriel.[citation needed] Most Christians believe that the Paraclete referred to in the Gospel of John, who was manifested on the day of Pentecost, is the Holy Spirit.[38][39] On the other hand, some Islamic scholars believe that the reference to the Paraclete is a prophecy of the coming of Muhammad.[40]

One of the key verses concerning the Paraclete is John 16:7:

"Nevertheless I tell you the truth: It is expedient for you that I go away; for if I go not away, the Comforter[Paraclete] will not come unto you; but if I go, I will send him unto you."

Salvation

The Catechism of the Catholic Church, the official doctrine document released by the Roman Catholic Church, has this to say regarding Muslims:

The Church's relationship with the Muslims. "The plan of salvation also includes those who acknowledge the Creator, in the first place amongst whom are the Muslims; these profess to hold the faith of Abraham, and together with us they adore the one, merciful God, mankind's judge on the last day."

— Catechism of the Catholic Church[41]

Protestant theology mostly emphasizes the necessity of faith in Jesus as a savior in order for

"The first and chief article is this: Jesus Christ, our God and Lord, died for our sins and was raised again for our justification (Romans 3:24–25). He alone is the Lamb of God who takes away the sins of the world (John 1:29), and God has laid on Him the iniquity of us all (Isaiah 53:6). All have sinned and are justified freely, without their own works and merits, by His grace, through the redemption that is in Christ Jesus, in His blood (Romans 3:23–25). This is necessary to believe. This cannot be otherwise acquired or grasped by any work, law or merit. Therefore, it is clear and certain that this faith alone justifies us ... Nothing of this article can be yielded or surrendered, even though heaven and earth and everything else falls (Mark 13:31)."

The Quran explicitly promises salvation for all those righteous Christians who were there before the arrival of Muhammad:

Indeed, the believers, Jews, Christians, and Sabians—whoever ˹truly˺ believes in Allah and the Last Day and does good will have their reward with their Lord. And there will be no fear for them, nor will they grieve.

The Quran also makes it clear that the Christians will be nearest in love to those who follow the Quran and praises Christians for being humble and wise:

You will surely find the most bitter towards the believers to be the Jews and polytheists and the most gracious to be those who call themselves Christian. That is because there are priests and monks among them and because they are not arrogant. When they listen to what has been revealed to the Messenger, you see their eyes overflowing with tears for recognizing the truth. They say, “Our Lord! We believe, so count us among the witnesses. Why should we not believe in Allah and the truth that has come to us? And we long for our Lord to include us in the company of the righteous.” So Allah will reward them for what they said with Gardens under which rivers flow, to stay there forever. And that is the reward of the good-doers.

Early and Medieval Christian writers on Islam and Muhammad

John of Damascus

In 746, John of Damascus (sometimes St. John of Damascus) wrote the Fount of Knowledge part two of which is entitled Heresies in Epitome: How They Began and Whence They Drew Their Origin.[43] In this work, John makes extensive reference to the Quran and, in John's opinion, its failure to live up to even the most basic scrutiny. The work is not exclusively concerned with the Ismaelites (a name for the Muslims as they claimed to have descended from Ismael) but all heresy. The Fount of Knowledge references several suras directly often with apparent incredulity.

From that time to the present a false prophet named Mohammed has appeared in their midst. This man, after having chanced upon the Old and New Testaments and likewise, it seems, having conversed with an

Mount Sinai, with God appearing in the sight of all the people in cloud, and fire, and darkness, and storm. And we say that all the Prophets from Moses on down foretold the coming of Christ and how Christ God (and incarnate Son of God) was to come and to be crucified and die and rise again, and how He was to be the judge of the living and dead. Then, when we say: 'How is it that this prophet of yours did not come in the same way, with others bearing witness to him? And how is it that God did not in your presence present this man with the book to which you refer, even as He gave the Law to Moses, with the people looking on and the mountain smoking, so that you, too, might have certainty?' – they answer that God does as He pleases. 'This,' we say, 'We know, but we are asking how the book came down to your prophet.' Then they reply that the book came down to him while he was asleep.[44]

Theophanes the Confessor

Theophanes the Confessor (died c.822) wrote a series of chronicles (284 onwards and 602–813 AD)[45][46][47] based initially on those of the better known George Syncellus. Theophanes reports about Muhammad thus:

At the beginning of his advent the misguided Jews thought he was the Messiah. ... But when they saw him eating camel meat, they realized that he was not the one they thought him to be, ... those wretched men taught him illicit things directed against us, Christians, and remained with him.

Whenever he came to

his wife became aware of this, she was greatly distressed, inasmuch as she, a noblewoman, had married a man such as he, who was not only poor, but also an epileptic. He tried deceitfully to placate her by saying, 'I keep seeing a vision of a certain angel called Gabriel, and being unable to bear his sight, I faint and fall down.'

Niketas

In the work A History of Christian-Muslim Relations,[48] Hugh Goddard mentions both John of Damascus and Theophanes and goes on to consider the relevance of Niketas Byzantios [clarification needed] who formulated replies to letters on behalf of Emperor Michael III (842-867). Goddard sums up Niketas' view:

In short, Muhammad was an ignorant charlatan who succeeded by imposture in seducing the ignorant barbarian

Arabsinto accepting a gross, blaspheming, idolatrous, demoniac religion, which is full of futile errors, intellectual enormities, doctrinal errors and moral aberrations.

Goddard further argues that Niketas demonstrates in his work a knowledge of the entire Quran, including an extensive knowledge of

11th century

Knowledge and depictions of Islam continued to be varied within the Christian West during the 11th century. For instance, the author(s) of the 11th century Song of Roland evidently had little actual knowledge of Islam. As depicted in this epic poem, Muslims erect statues of Mohammed and worship them, and Mohammed is part of an "Unholy Trinity" together with the Classical Greek Apollyon and Termagant, a completely fictional deity. This view, evidently confusing Islam with the pre-Christian Graeco-Roman Religion, appears to reflect misconceptions prevalent in Western Christian society at the time.

On the other hand, ecclesiastic writers such as

Similarities were occasionally acknowledged such as by Pope Gregory VII wrote in a letter to the Hammadid emir an-Nasir that both Christians and Muslims "worship and confess the same God though in diverse forms and daily praise".[50]

The Divine Comedy

In Dante Alighieri's Divine Comedy, Muhammad is in the ninth ditch of Malebolge, the eighth realm, designed for those who have caused schism; specifically, he was placed among the Sowers of Religious Discord. Muhammad is portrayed as split in half, with his entrails hanging out, representing his status as a heresiarch (Canto 28).

This scene is frequently shown in illustrations of the Divine Comedy. Muhammad is represented in a 15th-century

Catholic Church and Islam

Second Vatican Council and Nostra aetate

The question of Islam was not on the agenda when

Early in 1964,

The period between the first and second sessions saw the change of pontiff from Pope John XXIII to Pope Paul VI, who had been a member of the circle (the Badaliya) of the Islamologist Louis Massignon. Pope Paul VI chose to follow the path recommended by Maximos IV and he therefore established commissions to introduce what would become paragraphs on the Muslims in two different documents, one of them being Nostra aetate, paragraph three, the other being Lumen gentium, paragraph 16.[54]

The text of the final draft bore traces of Massignon's influence. The reference to

In Lumen gentium, the Second Vatican Council declares that the plan of salvation also includes Muslims, due to their professed monotheism.[55]

Recent Catholic-Islamic controversies

- For the controversy surrounding Muslim prayer in Spain, see Muslim campaign at Córdoba Cathedral

- For criticism of interfaith dialogue with Muslims, see Pierre Claverie#Relations with Islam

- For the controversy over whether Islam is a religion or a political system, see Raymond Leo Burke#Islam and immigration

- For the controversy over advice not to marry a Muslim and move to an Islamic country, see José Policarpo#Marriages with Muslim men

- For the controversy over whether Catholics may call God "Allah" if they want to, see Titular Roman Catholic Archbishop of Kuala Lumpur v Menteri Dalam Negeri

- For the controversy over remarks by Pope Benedict XVI, see Regensburg lecture and Pope Benedict XVI and Islam

Protestantism and Islam

Mormonism and Islam

Christianity and Druze

This section may contain material not related to the topic of the article. (October 2021) ) |

Christianity and

The relationship between the Druze and Christians has been characterized by harmony and coexistence,

Contact between Christians (members of the Maronite, Eastern Orthodox, Melkite and other churches) and the Unitarian Druze led to the presence of mixed villages and towns in Mount Lebanon, Jabal al-Druze,[79] Galilee, and Mount Carmel. The Maronites and the Druze founded modern Lebanon in the early eighteenth century, through the ruling and social system known as the "Maronite-Druze dualism" in Mount Lebanon Mutasarrifate.[80]

Christianity does not include belief in

Both faiths give a prominent place to Jesus:[84][85] Jesus is the central figure of Christianity, and in the Druze faith, Jesus is considered an important prophet of God,[84][85] being among the seven prophets who appeared in different periods of history.[86] Both religions venerated John the Baptist,[87] Saint George,[88] Elijah,[87] and other common figures.

Cultural influences

Scholars and intellectuals agree

During the

Artistic influences

See also

- Ashtiname of Muhammad

- Chrislam (Yoruba), a syncretist religion

- Christian influences in Islam

- Christian philosophy

- Christianity and other religions

- Christianity and war

- Crusades

- Constantinople

- Divisions of the world in Islam

- Islam and other religions

- Islamic philosophy

- Islam and war

- Muhammad's views on Christians

References

- ^ "Christianity".

- ^ "Religion by Country 2021". Archived from the original on 2020-07-30.

- ^ "Christianity".

- doi:10.1163/1573-3912_islam_COM_038 (inactive 31 January 2024).)(subscription required)

{{cite encyclopedia}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of January 2024 (link - ISBN 90-04-04743-3

- ISBN 9780759101906.

- ISBN 9780736949910.

- ^ The Oxford Dictionary of Islam, p.158

- ^ "Surah Al-'Ankabut – 46". Quran.com. Retrieved 2023-02-02.

- . Retrieved 14 March 2021.

- . Retrieved 14 March 2021.

- ^ * Chronology of Prophetic Events, Fazlur Rehman Shaikh (2001) p. 50 Ta-Ha Publishers Ltd.

- Quran 17:105

- ^ Nasr, Seyyed Hossein (2007). "Qurʾān". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Retrieved 24 September 2013.

- ^ a b Living Religions: An Encyclopaedia of the World's Faiths, Mary Pat Fisher, 1997, page 338, I.B. Tauris Publishers.

- ^ a b Quran 17:106

- ISBN 0-253-21627-3.

- ISBN 978-0-8264-4956-6.

- ^ Understanding the Qurán – Page xii, Ahmad Hussein Sakr – 2000

- ^ ISBN 978-0791405598.

- ISBN 978-1570758072.

- ^ "Surah An-Nisa' Verse 157 | 4:157 النساء - Quran O". qurano.com. Retrieved 2021-06-25.

- ^ a b "7 Things Muslims Should Know about Prophet 'Isa (as) | Muslim Hands UK". muslimhands.org.uk. 25 December 2020. Retrieved 2021-08-15.

- ISBN 9781449760137.

- ]

- ^

- Chronology of Prophetic Events, Fazlur Rehman Shaikh (2001) p. 50 Ta-Ha Publishers Ltd.

- Quran 17:105

- ^ Nasr, Seyyed Hossein (2007). "Qurʾān". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Retrieved 24 September 2013.

- ISBN 0-691-11461-7.

- ^ "Muhammad". PBS.

- ^ Encyclopedia of Islam, Online ed., "Waraqah bin. Nawfal".

- ^ Nickel, Gordon D. (January 2006). ""We Will Make Peace With You": The Christians of Najrān in Muqātil's Tafsir". Collectanea Christiana Orientalia.

- ^ "Al-Mizan (Al I Imran) | PDF | Quran | Islam". Scribd. Retrieved 2021-08-15.

- ISSN 1047-5141. – via General OneFile (subscription required)

- ISBN 9780759101906.

- ISBN 1-56744-489-X. Archived from the original on 2019-04-01. Retrieved 2017-05-06.)

{{cite book}}:|author=has generic name (help);|work=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - ^ "The Major Sins: Al-Kaba'r". Jannah.org.

- ^ "The Quranic Arabic Corpus – Translation". corpus.quran.com. Retrieved 2021-07-21.

- ^ "The Fundamentals of Tawhid (Islamic Monotheism)". ICRS (Indonesian Consortium of Religious Studies. 2010-10-30. Archived from the original on 2015-06-20. Retrieved 2015-10-28.

- ^ International Standard Bible Encyclopedia

- ISBN 9783161446481– via Google Books.

- S2CID 163407787.

- ^ "The Smalcald Articles," in Concordia: The Lutheran Confessions. Saint Louis: Concordia Publishing House, 2005, 289, Part two, Article 1.

- ^ "St. John of Damascus: Critique of Islam".

- ^ "St. John of Damascus: Critique of Islam".

- ^ Theophanes in English, on Mohammed gives an excerpt with all pertinent text as translated by Cyril Mango

- ^ The Chronicle of Theophanes Confessor (Byzantine and Near Eastern History AD 284–813). Translated with introduction and commentary by Cyril Mango and Geoffrey Greatrex, Oxford 1997. An updated version of the roger-pearse.com citation.

- ^ The Chronicle of Theophanes Anni Mundi 6095–6305 (A.D. 602–813) a more popularised but less rigorously studied translation of Theophanes chronicles

- ISBN 9780748610099– via Google Books.

- ^ Smit, Timothy (2009). "Pagans and Infidels, Saracens and Sicilians: Identifying Muslims in the Eleventh-Century Chronicles of Norman Italy". The Haskin Society Journal. 21: 87–112.

- ISBN 0374925658. Retrieved 10 December 2022.

- ^ Philip Willan (2002-06-24). "Al-Qaida plot to blow up Bologna church fresco". The Guardian.

- ^ Ayesha Akram (2006-02-11). "What's behind Muslim cartoon outrage". San Francisco Chronicle.

- ^ (History of Vatican II, pp. 142–43)

- ^ a b (Robinson, p. 195)

- ^ Lumen gentium, 16 Archived September 6, 2014, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Monash Arts" (PDF). 12 December 2023.

- ^ "Muslim-Christian Dialogue – Oxford Islamic Studies Online". Archived from the original on September 9, 2012.

- ^ Thomas Marsh and Orson Hyde Affidavit, for example; see also PBS's American Prophet: Prologue and Todd J. Harris, A Comparison of Muhammad and Joseph Smith in the Prophetic Pattern Archived 2011-11-14 at the Wayback Machine, a thesis submitted for a Master of Arts degree at Brigham Young University in 2007, footnotes on pages 1 and 2.

- ^ PBS's American Prophet: Prologue.

- ^ Thomas Marsh and Orson Hyde Affidavit, also Todd J. Harris, A Comparison of Muhammad and Joseph Smith in the Prophetic Pattern Archived 2011-11-14 at the Wayback Machine, a thesis submitted for a Master of Arts degree at Brigham Young University in 2007, footnotes on pages 1 and 2.

- ^ See, for example:Joseph Smith and Muhammad: The Similarities, and Eric Johnson,Joseph Smith and Muhammad, a book published by the "Mormonism Research Ministry" and offered for sale by the anti-Mormon "Utah Lighthouse Ministries".

- ^ See, for instance, Todd J. Harris, A Comparison of Muhammad and Joseph Smith in the Prophetic Pattern Archived 2011-11-14 at the Wayback Machine, a thesis submitted for a Master of Arts degree at Brigham Young University in 2007.

- ^ Haldane, David (2 April 2008). "U.S. Muslims share friendship, similar values with Mormons" – via LA Times.

- ^ World Muslim Congress: Mormons and Muslims; Mormon-Muslim Interfaith Ramadan Dinner.

- ^ "Are the Druze People Arabs or Muslims? Deciphering Who They Are". Arab America. 8 August 2018. Retrieved 13 April 2020.

- ^ James Lewis (2002). The Encyclopedia of Cults, Sects, and New Religions. Prometheus Books. Retrieved 13 May 2015.

- ISBN 9781317931737.

the Druze had been able to live in harmony with the Christian

- ISBN 9789652260499.

.. Europeans who visited the area during this period related that the Druze "love the Christians more than the other believers," and that they "hate the Turks, the Muslims and the Arabs [Bedouin] with an intense hatred.

- ^ CHURCHILL (1862). The Druzes and the Maronites. Montserrat Abbey Library. p. 25.

..the Druzes and Christians lived together in the most perfect harmony and good-will..

- ^ Hobby (1985). Near East/South Asia Report. Foreign Broadcast Information Service. p. 53.

the Druzes and the Christians in the Shuf Mountains in the past lived in complete harmony..

- ISBN 9780520087828. Retrieved 2015-04-16.

- ISBN 0-903983-92-3.

- ISBN 9780313332197.

some Christians (mostly from the Orthodox faith), as well as Druze, converted to Protestantism...

- ISBN 9780313332197.

Many of the Druze have chosen to deemphasize their ethnic identity, and some have officially converted to Christianity.

- ISBN 9781414448916.

US Druze settled in small towns and kept a low profile, joining Protestant churches (usually Presbyterian or Methodist) and often Americanizing their names..

- ^ Granli, Elisabet (2011). "Religious conversion in Syria : Alawite and Druze believers". University of Oslo.

- ^ Mishaqa, p. 23.

- ISBN 978-1-4381-1025-7. Retrieved 2013-05-25.

- ^ The Druze and Assad: Strategic Bedfellows

- ISBN 9780817916664.

the Maronites and the Druze, who founded Lebanon in the early eighteenth century.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-7864-1375-1, retrieved 4 April 2012

- ISBN 9780863722493.

- ISBN 9780852295533.

Druze religious beliefs developed out of Isma'ill teachings. Various Jewish, Christian, Gnostic, Neoplatonic, and Iranian elements, however, are combined under a doctrine of strict monotheism.

- ^ ISBN 9781465546623.

- ^ ISBN 9781903900369.

- ISBN 9781135355616.

...Druze believe in seven prophets: Adam, Noah, Abraham, Moses, Jesus, Muhammad, and Muhammad ibn Ismail ad-Darazi..

- ^ ISBN 978-1442246171.

- ISBN 9780191647666.

- ISBN 0-7486-0455-3, p. 4

- ISBN 978-0-226-07080-3.

- ISBN 978-0-19-829388-0. Archivedfrom the original on 10 March 2021. Retrieved 21 October 2016.

- ISBN 9781351510721.

- ISBN 9781351510721.

Christian contributions to art, culture, and literature in the Arab-Islamic world; Christian contributions education and social advancement in the region.

- ISBN 0-7486-0455-3, p.4

- ISBN 9780226070803. Retrieved 11 Feb 2014.

- ^ Ferguson, Kitty Pythagoras: His Lives and the Legacy of a Rational Universe Walker Publishing Company, New York, 2008, (page number not available – occurs toward end of Chapter 13, "The Wrap-up of Antiquity"). "It was in the Near and Middle East and North Africa that the old traditions of teaching and learning continued, and where Christian scholars were carefully preserving ancient texts and knowledge of the ancient Greek language."

- ^ Rémi Brague, Assyrians contributions to the Islamic civilization Archived 2013-09-27 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Britannica, Nestorian

- ^ George Saliba (2006-04-27). "Islamic Science and the Making of Renaissance Europe". Library of Congress. Archived from the original on 29 June 2006. Retrieved 2008-03-01.

- ^ Dag Nikolaus Hasse (2014). "Influence of Arabic and Islamic Philosophy on the Latin West". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved 2020-06-03.

- ISBN 9780071417518– via Google Books.

- ISBN 9781932805246– via Google Books.

Further reading

- Abdiyah Akbar Abdul-Haqq, Sharing Your [Christian] Faith with a Muslim, Minneapolis: Bethany House Publishers, 1980. ISBN 0-87123-553-6

- Giulio Basetti-Sani, The Koran in the Light of Christ: a Christian Interpretation of the Sacred Book of Islam, trans. by W. Russell-Carroll and Bede Dauphinee, Chicago, Ill.: Franciscan Herald Press, 1977. ISBN 0-8199-0713-8

- ISBN 2-7189-0186-1

- Kenneth Cragg, The Call of the Minaret, Third ed., Oxford: Oneworld [sic] Publications, 2000, xv, 358 p. ISBN 1-85168-210-4

- Maria Jaoudi, Christian & Islamic Spirituality: Sharing a Journey, Mahwah, N.J.: Paulist Press, 1992. iii, 103 p. ISBN 0-8091-3426-8

- Jane Dammen McAuliffe, Qur'anic Christians: An Analysis of Classical and Modern Exegesis, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1991. ISBN 0-521-36470-1

- Frithjof Schuon, Christianity/Islam: Essays on Esoteric Ecumenicism, in series, The Library of Traditional Wisdom, Bloomington, Ind.: World Wisdom Books, cop. 1985. vii, 270 p. N.B.: Trans. from French. ISBN 0-941532-05-4; the ISBN on the verso of the t.p. surely is erroneous.

- Mark D. Siljander and John David Mann, A Deadly Misunderstanding: a Congressman's Quest to Bridge the Muslim-Christian Divide, New York: Harper One, 2008. ISBN 978-0-06-143828-8.

- ISBN 978-1938983283.

- Thomas, David, Muhammad in Medieval Christian-Muslim Relations (Medieval Islam), in Muhammad in History, Thought, and Culture: An Encyclopedia of the Prophet of God (2 vols.), Edited by C. Fitzpatrick and A. Walker, Santa Barbara, ABC-CLIO, 2014, Vol. I, pp. 392–400. 1610691776

External links

- Hasib Sabbagh: A Legacy of Understanding from the Dean Peter Krogh Foreign Affairs Digital Archives

- "I'm Right, You're Wrong, Go to Hell" – Religions and the meeting of civilization by Bernard Lewis

- Islam & Christianity (IRAN & GEORGIA) News Photos