Archdiocese of Carthage

Archdiocese of Carthage Archidioecesis Carthaginensis | ||

|---|---|---|

| Bishopric | ||

Titular archbishop | Vacant since 1979 | |

The Archdiocese of Carthage, also known as the Church of Carthage, was a

The Church of Carthage thus was to the

In the 6th century, turbulent controversies in teachings affected the diocese: Donatism, Arianism, Manichaeism, and Pelagianism. Some proponents established their own parallel hierarchies.

The city of Carthage fell to the Muslim conquest of the Maghreb with the Battle of Carthage (698). The episcopal see remained but Christianity declined under persecution. The last resident bishop, Cyriacus of Carthage, was documented in 1076.

In 1518, the Archdiocese of Carthage was revived as a

History

Antiquity

Earliest bishops

In Christian traditions, some accounts give as the first bishop of Carthage

Primacy

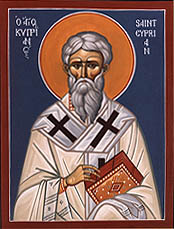

In the 3rd century, at the time of Cyprian, the bishops of Carthage exercised a real though not formalized primacy in the

Division

Cyprian faced opposition within his own diocese over the question of the proper treatment of the lapsi who had fallen away from the Christian faith under persecution.[17]

More than eighty bishops, some from distant frontier regions of

A division in the church that came to be known as the

The occasionally violent controversy has been characterized as a struggle between opponents and supporters of the Roman system. The most articulate North African critic of the Donatist position, which came to be called a heresy, was

Successors of Cyprian until before the Vandal invasion

The immediate successors of Cyprian were Lucianus and Carpophorus, but there is disagreement about which of the two was earlier. A bishop Cyrus, mentioned in a lost work by

By the end of the 4th century, the settled areas had become Christianized, and some Berber tribes had converted en masse.

The next bishop was

, a relative of Donatus, resulted in the largest Maximian schism within the Donatist movement.Bishops under the Vandals

Capreolus was bishop of Carthage when the Vandals conquered the province. Unable for that reason to attend the

Middle Ages

Praetorian prefecture of Africa

The

Islamic conquest of Mahgreb

Last resident bishops

At the beginning of the 8th century and at the end of the 9th, Carthage still appears in lists of dioceses over which the Patriarch of Alexandria claimed jurisdiction.

Two letters of

In each of the two letters, Pope Leo declares that, after the Bishop of Rome, the first archbishop and chief metropolitan of the whole of Africa is the bishop of Carthage,[19] while the bishop of Gummi, whatever his dignity or power, will act, except for what concerns his own diocese, like the other African bishops, by consultation with the archbishop of Carthage. In the letter addressed to Petrus and Ioannes, Pope Leo adds to his declaration of the position of the bishop of Carthage the eloquent[20] declaration: "... nor can he, for the benefit of any bishop in the whole of Africa lose the privilege received once for all from the holy Roman and apostolic see, but he will hold it until the end of the world as long as the name of our Lord Jesus Christ is invoked there, whether Carthage lie desolate or whether it some day rise glorious again".[21] When in the 19th century the residential see of Carthage was for a while restored, Cardinal

Later, an archbishop of Carthage named Cyriacus was imprisoned by the Arab rulers because of an accusation by some Christians. Pope Gregory VII wrote him a letter of consolation, repeating the hopeful assurances of the primacy of the Church of Carthage, "whether the Church of Carthage should still lie desolate or rise again in glory". By 1076, Cyriacus was set free, but there was only one other bishop in the province. These are the last of whom there is mention in that period of the history of the see.[23][24]

Decline

After the

Some primary accounts including Arabic ones in 10th century mention persecutions of the Church and measures undertaken by Muslim rulers to suppress it. A schism among the African churches developed by the time of

The

List of bishops

- Crescentius (c. 80)

- Epenetus (c. 115)

- Speratus (180)

- Optatus (203)

- Agrippinus (c. 240)

- Donatus I (?–248)

- Cyprian(248–258)

- Maximus (251), Novatianistanti-bishop

- Fortunatus (252), anti-bishop

- Maximus (251),

- Lucianus (3rd century)

- Carpophorus (3rd century)

- Cyrus (3rd century)

- Caecilianus (311–325)

- Donatistbishop

- Donatus II (c. 313 – c. 350×355), Donatist bishop

- Rufus (337×340)

- Gratus (fl. 343/4–345×348)

- Parmenianus (c. 350×355 – c. 391), Donatist bishop

- Restitutus (359)

- Geneclius (? – 390×393)

- Aurelius (fl. 393–426)

- Primianus (c. 391), Donatist bishop

- Maximianus(c. 392), Donatist bishop

- Capreolus (fl. 431–435)

- Quodvultdeus (c. 437 – c. 454)

- Deogratias(454–457/8)

- sede vacante

- Eugenius (481–505)

- sede vacante

- Boniface (523 – c. 535)

- Reparatus (535–552)

- Primosus or Primasius (552 – c. 565)

- Publianus (fl. c. 565–581)

- Dominicus (fl. 592–601)

- Licinianus (d. 602)

- Fortunius

- Victor (646–?)[29]

- ...

- Stephen

- ...

- James (974×983)

- ...

- Thomas (1054)

- Cyriacus] (1076)

Titular see

Today, the Archdiocese of Carthage remains as a titular see of the Catholic Church, albeit vacant. The equivalent contemporary entity for the historical geography in continuous operation would be the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Tunis, established in 1884.

See also

- North Africa during Antiquity

- Early African church

- Primate of Africa

- Councils of Carthage

- Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Tunis

References

- ISBN 9781438110271.

- ^ Herbermann, Charles, ed. "Africa". Catholic Encyclopedia. (New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1913).

- ^ François Decret, Early Christianity in North Africa (James Clarke & Co, 25 Dec. 2014) p86.

- ^ Leo the Great, Letters89.

- ^ Plummer, Alfred (1887). The Church of the Early Fathers: External History. Longmans, Green and Company. pp. 109.

church of africa carthage.

- ^ a b Benham, William (1887). The Dictionary of Religion. Cassell. pp. 1013.

- ^ a b Ekonomou 2007, p. 22.

- ^ a b Gonzáles, Justo L. (2010). "The Early Church to the Dawn of the Reformation". The Story of Christianity. Vol. 1. New York: HarperCollins Publishers. pp. 91–93.

- ^ OCLC 609155089.

- OCLC 1084084.

- S2CID 195430375.

- ^ "Cartagine". Enciclopedia Italiana di scienze, lettere ed arti (in Italian). 1931 – via treccani.it.

- OCLC 613240276.

- OCLC 680468850.

- OCLC 895344169.. Vol. 6.)

Gams "ignored a number of scattered dissertations which would have rectified, on a multitude of points, his uncertain chronology" and Leclercq suggests that "larger information must be sought in extensive documentary works." (Leclercq, Henri (1909). "Pius Bonifacius Gams". Catholic Encyclopedia - ^ a b Hassett, Maurice M. (1908). . In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 3. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- OCLC 680510498.

- ^ (Contractus), Hermannus (2008-08-20). "Patrologia Latina, vol. 143, coll. 727–731". Retrieved 2019-01-17.

- ^ Primus archiepiscopus et totius Africae maximus metropolitanus est Carthaginiensis episcopus

- ^ Mas-Latrie, Louis de (1883). "L'episcopus Gummitanus et la primauté de l'évêque de Carthage". Bibliothèque de l'école des chartes. 44 (44): 77. Retrieved 15 January 2015.

- ^ nec pro aliquo episcopo in tota Africa potest perdere privilegium semel susceptum a sancta Romana et apostolica sede: sed obtinebit illud usque in finem saeculi, et donec in ea invocabitur nomen Domini nostri Iesu Christi, sive deserta iaceat Carthago, sive gloriosa resurgat aliquando

- ^ Sollier, Joseph F. (1910). . In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 9. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- ^ Bouchier, E.S. (1913). Life and Letters in Roman Africa. Oxford: Blackwells. p. 117. Retrieved 15 January 2015.

- ^ François Decret, Early Christianity in North Africa (James Clarke & Co, 2011) p200.

- ^ Der Nahe und Mittlere Osten By Heinz Halm, page 99

- ^ Ancient African Christianity: An Introduction to a Unique Context and Tradition By David E. Wilhite, page 332-334

- ^ "citing Mohamed Talbi, "Le Christianisme maghrébin", in M. Gervers & R. Bikhazi, Indigenous Christian Communities in Islamic Lands; Toronto, 1990; pp. 344–345".

- ISBN 9781843838098., page 103-104

- ISBN 9781960069719.

Bibliography

- François Decret, Le christianisme en Afrique du Nord ancienne, Seuil, Paris, 1996 (ISBN 2020227746)

- Ekonomou, Andrew J. (2007). Byzantine Rome and the Greek Popes: Eastern influences on Rome and the papacy from Gregory the Great to Zacharias, A.D. 590–752. Lexington Books.

- Paul Monceaux, Histoire littéraire de l'Afrique chrétienne depuis les origines jusqu'à l'invasion arabe (7 volumes : Tertullien et les origines – saint Cyprien et son temps – le IV, d'Arnobe à Victorin – le Donatisme – saint Optat et les premiers écrivains donatistes – la littérature donatiste au temps de saint Augustin – saint Augustin et le donatisme), Paris, Ernest Leroux, 1920.

External links

- Leclercq, Henri (1907). . Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 1.

- (in French) Les racines africaines du christianisme latin par Henri Teissier, Archevêque d'Alger