Church of the East

| Church of the East | |

|---|---|

| ܥܕܬܐ ܕܡܕܢܚܐ | |

| Founder | Jesus Christ by sacred tradition Thomas the Apostle |

| Origin | Apostolic Age, by its tradition Edessa,[5][6] Mesopotamia[1][note 1] |

| Branched from | Nicene Christianity |

| Separations | Its schism of 1552 divided it originally into two patriarchates, and later four, but by 1830 it returned to two, one of which is now the Chaldean Catholic Church, while the other sect split further in 1968 into the Assyrian Church of the East and the Ancient Church of the East. |

| Other name(s) | Nestorian Church, Persian Church, East Syrian Church, Assyrian Church, Babylonian Church[11] |

| Part of a series on |

| Eastern Christianity |

|---|

|

The Church of the East (

Having its origins in the pre-Sasanian Mesopotamia, the Church of the East developed its own unique form of Christian theology and liturgy. During the early modern period, a series of schisms gave rise to rival patriarchates, sometimes two, sometimes three.[16] In the latter half of the 20th century the traditionalist patriarchate of the church underwent a split into two rival patriarchates, namely the Assyrian Church of the East and the Ancient Church of the East, which continue to follow the traditional theology and liturgy of the mother church. The Chaldean Catholic Church based in Iraq and the Syro-Malabar Church in India are two Eastern Catholic churches which also claim the heritage of the Church of the East.[2]

The Church of the East organized itself initially in the year 410 as the

The Church of the East, which was part of the Great Church, shared communion with those in the Roman Empire until the Council of Ephesus condemned Nestorius in 431.[1] Supporters of Nestorius took refuge in Sasanian Persia, where the Church refused to condemn Nestorius and became accused of Nestorianism, a heresy attributed to Nestorius. It was therefore called the Nestorian Church by all the other Eastern churches, both Chalcedonian and non-Chalcedonian, and by the Western Church. Politically the Sasanian and Roman empires were at war with each other, which forced the Church of the East to distance itself from the churches within Roman territory.[18][19][20]

More recently, the "Nestorian" appellation has been called "a lamentable misnomer",[21][22] and theologically incorrect by scholars.[15] However, the Church of the East started to call itself Nestorian, it anathematized the Council of Ephesus, and in its liturgy Nestorius was mentioned as a saint.[23][24] In 544, the general Council of the Church of the East approved the Council of Chalcedon at the Synod of Mar Aba I.[25][5]

Continuing as a dhimmi community under the Sunni Caliphate after the Muslim conquest of Persia (633–654), the Church of the East played a major role in the history of Christianity in Asia. Between the 9th and 14th centuries, it represented the world's largest Christian denomination in terms of geographical extent, and in the Middle Ages was one of the three major Christian powerhouses of Eurasia alongside Catholicism and Greek Orthodoxy.[26] It established dioceses and communities stretching from the Mediterranean Sea and today's Iraq and Iran, to India (the Saint Thomas Syrian Christians of Kerala), the Mongol kingdoms and Turkic tribes in Central Asia, and China during the Tang dynasty (7th–9th centuries). In the 13th and 14th centuries, the church experienced a final period of expansion under the Mongol Empire, where influential Church of the East clergy sat in the Mongol court.

Even before the Church of the East underwent a rapid decline in its field of expansion in

The Church faced a major

Background

- (Not shown are ante-Nicene, nontrinitarian, and restorationist denominations.)

The Church of the East's declaration in 424 of the independence of its head, the

In the 6th century and thereafter, the Church of the East expanded greatly, establishing communities in India (the Saint Thomas Syrian Christians), among the Mongols in Central Asia, and in China, which became home to a thriving community under the Tang dynasty from the 7th to the 9th century. At its height, between the 9th and 14th centuries, the Church of the East was the world's largest Christian church in geographical extent, with dioceses stretching from its heartland in Upper Mesopotamia to the Mediterranean Sea and as far afield as China, Mongolia, Central Asia, Anatolia, the Arabian Peninsula and India.

From its peak of geographical extent, the church entered a period of rapid decline that began in the 14th century, due largely to outside influences. The Chinese Ming dynasty overthrew the Mongols (1368) and ejected Christians and other foreign influences from China, and many Mongols in Central Asia converted to Islam. The Muslim Turco-Mongol leader Timur (1336–1405) nearly eradicated the remaining Christians in the Middle East. Nestorian Christianity remained largely confined to communities in Upper Mesopotamia and the Saint Thomas Syrian Christians of the Malabar Coast in the Indian subcontinent.

In the early modern period, the schism of 1552 led to a series of internal divisions and ultimately to its branching into three separate churches: the Chaldean Catholic Church, in full communion with the Holy See, the independent Assyrian Church of the East and the Ancient Church of the East.[33]

Description as Nestorian

After 431, the state authorities in the Roman Empire suppressed Nestorianism, a reason for Christians under Persian rule to favour it and so allay suspicion that their loyalty lay with the hostile Christian-ruled empire.[36][37]

It was in the aftermath of the slightly later Council of Chalcedon (451), that the Church of the East formulated a distinctive theology. The first such formulation was adopted at the Synod of Beth Lapat in 484. This was developed further in the early seventh century, when in an at first successful war against the Byzantine Empire the Sasanid Persian Empire incorporated broad territories populated by West Syrians, many of whom were supporters of the Miaphysite theology of Oriental Orthodoxy which its opponents term "Monophysitism" (Eutychianism), the theological view most opposed to Nestorianism. They received support from Khosrow II, influenced by his wife Shirin. Shirin was a member of the Church of East, but later joined the miaphysite church of Antioch.[citation needed]

Drawing inspiration from

The justice of imputing Nestorianism to Nestorius, whom the Church of the East venerated as a saint, is disputed.[46][21][47] David Wilmshurst states that for centuries "the word 'Nestorian' was used both as a term of abuse by those who disapproved of the traditional East Syrian theology, as a term of pride by many of its defenders [...] and as a neutral and convenient descriptive term by others. Nowadays it is generally felt that the term carries a stigma".[48] Sebastian P. Brock says: "The association between the Church of the East and Nestorius is of a very tenuous nature, and to continue to call that church 'Nestorian' is, from a historical point of view, totally misleading and incorrect – quite apart from being highly offensive and a breach of ecumenical good manners".[49]

Apart from its religious meaning, the word "Nestorian" has also been used in an ethnic sense, as shown by the phrase "Catholic Nestorians".[50][51][52][53]

In his 1996 article, "The 'Nestorian' Church: a lamentable misnomer", published in the Bulletin of the John Rylands Library, Sebastian Brock, a Fellow of the British Academy, lamented the fact that "the term 'Nestorian Church' has become the standard designation for the ancient oriental church which in the past called itself 'The Church of the East', but which today prefers a fuller title 'The Assyrian Church of the East'. Such a designation is not only discourteous to modern members of this venerable church, but also − as this paper aims to show − both inappropriate and misleading".[54]

Organisation and structure

At the

The Church of the East had, like other churches, an

For most of its history the church had six or so Interior Provinces. In 410, these were listed in the hierarchical order of:

Scriptures

The

The

The New Testament of the Peshitta, which originally excluded certain disputed books (Second Epistle of Peter, Second Epistle of John, Third Epistle of John, Epistle of Jude, Book of Revelation), had become the standard by the early 5th century.

Iconography

It was often said in the 19th century that the Church of the East was opposed to religious images of any kind. The cult of the image was never as strong in the

There is both literary and archaeological evidence for the presence of images in the church. Writing in 1248 from

An illustrated 13th-century Nestorian Peshitta Gospel book written in Estrangela from northern Mesopotamia or Tur Abdin, currently in the State Library of Berlin, proves that in the 13th century the Church of the East was not yet aniconic.[62] The Nestorian Evangelion preserved in the Bibliothèque nationale de France contains an illustration depicting Jesus Christ in the circle of a ringed cross surrounded by four angels.[63] Three Syriac manuscripts from early 19th century or earlier—they were published in a compilation titled The Book of Protection by Hermann Gollancz in 1912—contain some illustrations of no great artistic worth that show that use of images continued.

A life-size male stucco figure discovered in a late-6th-century church in Seleucia-Ctesiphon, beneath which were found the remains of an earlier church, also shows that the Church of the East used figurative representations.[62]

-

Palm Sunday procession of Nestorian clergy in a 7th- or 8th-century wall painting from a church at Karakhoja, Chinese Turkestan

-

Mogao Christian painting, a late-9th-century silk painting preserved in the British Museum.

-

Feast of the Discovery of the Cross, from a 13th-century Nestorian Peshitta Gospel book written in Estrangela, preserved in the SBB.

-

An angel announces the resurrection of Christ to Mary and Mary Magdalene, from the Nestorian Peshitta Gospel.

-

The twelve apostles are gathered around Peter at Pentecost, from the Nestorian Peshitta Gospel.

-

Portraits of the Four Evangelists, from a gospel lectionary according to the Nestorian use. Mosul, Iraq, 1499.

-

Drawing of a rider (Entry into Jerusalem), a lost wall painting from the Nestorian church at Khocho, 9th century.

-

Nestorian Christian statuette probably from Imperial China

-

Anikova Plate, showing the Siege of Jericho. It was probably made in and for a Sogdian Nestorian Christian community located in Semirechye. 9th–10th century.

-

The Grigorovskoye Plate: Paten with biblical scenes in medallions, counterclockwise from bottom left: women at the empty tomb, the crucifixion, and the Ascension. Semirechye, 9th–10th century.[64]

-

Detail of the rubbing of the Nestorian pillar of Luoyang, discovered in Luoyang. 9th century.

-

Detail of the rubbing of the Nestorian pillar of Luoyang, discovered in Luoyang. 9th century.

Early history

Although the Nestorian community traced their history to the 1st century AD, the Church of the East first achieved official state recognition from the Sasanian Empire in the 4th century with the accession of Yazdegerd I (reigned 399–420) to the throne of the Sasanian Empire. The policies of the Sasanian Empire, which encouraged syncretic forms of Christianity, greatly influenced the Church of the East.[65]

The early Church had branches that took inspiration from Neo-Platonism,[66][67] other Near Eastern religions[68][65] like Judaism,[69] and other forms of Christianity.[65]

In 410, the

Under pressure from the Sasanian Emperor, the Church of the East sought to increasingly distance itself from the

Thus, the Mesopotamian churches did not send representatives to the various church councils attended by representatives of the "

The theological controversy that followed the Council of Ephesus in 431 proved a turning point in the Christian Church's history. The Council condemned as heretical the Christology of Nestorius, whose reluctance to accord the Virgin Mary the title Theotokos "God-bearer, Mother of God" was taken as evidence that he believed two separate persons (as opposed to two united natures) to be present within Christ.

The Sasanian Emperor, hostile to the Byzantines, saw the opportunity to ensure the loyalty of his Christian subjects and lent support to the

Parthian and Sasanian periods

Christians were already forming communities in

These early Christian communities in Mesopotamia, Elam, and Fars were reinforced in the 4th and 5th centuries by large-scale deportations of Christians from the eastern

Meanwhile, in the Roman Empire, the

Now firmly established in the Persian Empire, with centres in Nisibis,

By the end of the 5th century and the middle of the 6th, the area occupied by the Church of the East included "all the countries to the east and those immediately to the west of the Euphrates", including the Sasanian Empire, the

The Church of the East also flourished in the kingdom of the

Islamic rule

After the Sasanian Empire was

Patriarch

Nestorian Christians made substantial contributions to the Islamic

Expansion

After the split with the Western World and synthesis with Nestorianism, the Church of the East expanded rapidly due to missionary works during the medieval period.

India

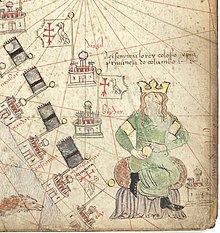

, identified as Christian due to the early Christian presence there)[100] in the contemporary Catalan Atlas of 1375.[101][102] The caption above the king of Kollam reads: Here rules the king of Colombo, a Christian.[103] The black flags (

, identified as Christian due to the early Christian presence there)[100] in the contemporary Catalan Atlas of 1375.[101][102] The caption above the king of Kollam reads: Here rules the king of Colombo, a Christian.[103] The black flags ( ) on the coast belong to the Delhi Sultanate.

) on the coast belong to the Delhi Sultanate.The

In the 12th century Indian Nestorianism engaged the Western imagination in the figure of

Sri Lanka

Nestorian Christianity is said to have thrived in Sri Lanka with the patronage of King Dathusena during the 5th century. There are mentions of involvement of Persian Christians with the Sri Lankan royal family during the Sigiriya Period. Over seventy-five ships carrying Murundi soldiers from Mangalore are said to have arrived in the Sri Lankan town of Chilaw most of whom were Christians. King Dathusena's daughter was married to his nephew Migara who is also said to have been a Nestorian Christian, and a commander of the Sinhalese army. Maga Brahmana, a Christian priest of Persian origin is said to have provided advice to King Dathusena on establishing his palace on the

The Anuradhapura Cross discovered in 1912 is also considered to be an indication of a strong Nestorian Christian presence in Sri Lanka between the 3rd and 10th century in the then capitol of Anuradhapura of Sri Lanka.[109][110][111][112]

China

Christianity reached China by 635, and its relics can still be seen in Chinese cities such as

Nestorian Christianity thrived in China for approximately 200 years, but then faced persecution from Emperor Wuzong of Tang (reigned 840–846). He suppressed all foreign religions, including Buddhism and Christianity, causing the church to decline sharply in China. A Syrian monk visiting China a few decades later described many churches in ruin. The church disappeared from China in the early 10th century, coinciding with the collapse of the Tang dynasty and the tumult of the next years (the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms period).[116]

Christianity in China experienced a significant revival during the Mongol-created Yuan dynasty, established after the Mongols had conquered China in the 13th century. Marco Polo in the 13th century and other medieval Western writers described many Nestorian communities remaining in China and Mongolia; however, they clearly were not as active as they had been during Tang times.

Mongolia and Central Asia

The Church of the East enjoyed a final period of expansion under the

Jerusalem and Cyprus

Decline

The expansion was followed by a decline. There were 68 cities with resident Church of the East bishops in the year 1000; in 1238 there were only 24, and at the death of Timur in 1405, only seven. The result of some 20 years under Öljaitü, ruler of the Ilkhanate from 1304 to 1316, and to a lesser extent under his predecessor, was that the overall number of the dioceses and parishes was further reduced.[121]

When

Schisms

From the middle of the 16th century, and throughout following two centuries, the Church of the East was affected by several internal schisms. Some of those schisms were caused by individuals or groups who chose to accept union with the Catholic Church. Other schisms were provoked by rivalry between various fractions within the Church of the East. Lack of internal unity and frequent change of allegiances led to the creation and continuation of separate patriarchal lines. In spite of many internal challenges, and external difficulties (political oppression by Ottoman authorities and frequent persecutions by local non-Christians), the traditional branches of the Church of the East managed to survive that tumultuous period and eventually consolidate during the 19th century in the form of the Assyrian Church of the East. At the same time, after many similar difficulties, groups united with the Catholic Church were finally consolidated into the Chaldean Catholic Church

Schism of 1552

Around the middle of the fifteenth century Patriarch Shemʿon IV Basidi made the patriarchal succession hereditary – normally from uncle to nephew. This practice, which resulted in a shortage of eligible heirs, eventually led to a schism in the Church of the East, creating a temporarily Catholic offshoot known as the Shimun line.

Sulaqa went to Rome, arriving on 18 November 1552, and presented a letter, drafted by his supporters in Mosul, setting out his claim and asking that the Pope consecrate him as Patriarch. On 15 February 1553 he made a twice-revised profession of faith judged to be satisfactory, and by the bull Divina Disponente Clementia of 20 February 1553 was appointed "Patriarch of Mosul in Eastern Syria"[132] or "Patriarch of the Church of the Chaldeans of Mosul" (Chaldaeorum ecclesiae Musal Patriarcha).[133] He was consecrated bishop in St. Peter's Basilica on 9 April. On 28 April Pope Julius III gave him the pallium conferring patriarchal rank, confirmed with the bull Cum Nos Nuper. These events, in which Rome was led to believe that Shemʿon VII Ishoʿyahb was dead, created within the Church of the East a lasting schism between the Eliya line of Patriarchs at Alqosh and the new line originating from Sulaqa. The latter was for half a century recognised by Rome as being in communion, but that reverted to both hereditary succession and Nestorianism and has continued in the Patriarchs of the Assyrian Church of the East.[131][134]

Sulaqa left Rome in early July and in Constantinople applied for civil recognition. After his return to Mesopotamia, he received from the Ottoman authorities in December 1553 recognition as head of "the Chaldean nation after the example of all the Patriarchs". In the following year, during a five-month stay in

The Eliya and Shimun lines

This new Catholic line founded by Sulaqa maintained its seat at

The Eliya-line Patriarch Shemon VII Ishoyahb (1539–1558), who resided in the Rabban Hormizd Monastery near Alqosh, continued to actively oppose union with Rome, and was succeeded by his nephew Eliya (designated as Eliya "VII" in older historiography,[137][138] but renumbered as Eliya "VI" in recent scholarly works).[139][140][141] During his Patriarchal tenure, from 1558 to 1591, the Church of the East preserved its traditional christology and full ecclesiastical independence.[142]

The next Shimun Patriarch was likely

Two Nestorian patriarchs

The next Eliya Patriarch, Eliya VII (VIII) (1591–1617), negotiated on several occasions with the Catholic Church, in 1605, 1610 and 1615–1616, but without final resolution.[147] This likely alarmed Shimun X, who in 1616 sent to Rome a profession of faith that Rome found unsatisfactory, and another in 1619, which also failed to win him official recognition.[147] Wilmshurst says it was this Shimun Patriarch who reverted to the "old faith" of Nestorianism,[144][148] leading to a shift in allegiances that won for the Eliya line control of the lowlands and of the highlands for the Shimun line. Further negotiations between the Eliya line and the Catholic Church were cancelled during the Patriarchal tenure of Eliya VIII (IX) (1617–1660).[149]

The next two Shimun Patriarchs, Shimun XI Eshuyow (1638–1656) and Shimun XII Yoalaha (1656–1662), wrote to the Pope in 1653 and 1658, according to Wilmshurst, while Heleen Murre speaks only of 1648 and 1653. Wilmshurst says Shimun XI was sent the pallium, though Heleen Murre argues official recognition was given to neither. A letter suggests that one of the two was removed from office (presumably by Nestorian traditionalists) for pro-Catholic leanings: Shimun XI according to Heleen Murre, probably Shimun XII according to Wilmshurst.[150][144]

The Josephite line

As the Shimun line "gradually returned to the traditional worship of the Church of the East, thereby losing the allegiance of the western regions",

In 1771,

Consolidation of patriarchal lines

When

This also ended the rivalry between the senior Eliya line and the junior Shimun line, as

Accordingly, Joachim Jakob remarks that the original Patriarchate of the Church of the East (the Eliya line) entered into union with Rome and continues down to today in the form of the Chaldean [Catholic] Church,[161] while the original Patriarchate of the Chaldean Catholic Church (the Shimun line) continues today in the Assyrian Church of the East.

See also

- Ancient Church of the East

- Assyrian Genocide

- Chaldean Catholic Church

- Christianity in Eastern Arabia

- Council of Seleucia-Ctesiphon (410)

- Dioceses of the Church of the East after 1552

- Dioceses of the Church of the East to 1318

- Dioceses of the Church of the East, 1318–1552

- List of patriarchs of the Church of the East

- Patriarchs of the Church of the East

- Schism of the Three Chapters

- Synod of Beth Lapat

- Syriac Christianity

- Syriac Orthodox Church

Explanatory notes

- Nestorian Schism". However, the Church of the East already existed as a separate organisation in 431, and the name of Nestorius is not mentioned in any of the acts of the Church's synods up to the 7th century.[7] Christian communities isolated from the church in the Roman Empire likely already existed in Persia from the 2nd century.[8] The independent ecclesiastical hierarchy of the Church developed over the course of the 4th century,[9] and it attained its full institutional identity with its establishment as the officially recognized Christian church in Persia by Shah Yazdegerd I in 410.[10]

- ^ The "Nestorian" label is popular, but it has been contentious, derogatory and considered a misnomer. See the § Description as Nestorian section for the naming issue and alternate designations for the church.

Citations

- ^ S2CID 160590164.

- ^ a b Baum & Winkler 2003, p. 2.

- ^ Stewart 1928, p. 15.

- ^ Vine, Aubrey R. (1937). The Nestorian Churches. London: Independent Press. p. 104.

- ^ a b Meyendorff 1989, p. 287-289.

- ISBN 9783161503047.

- ^ Brock 2006, p. 8.

- ^ Brock 2006, p. 11.

- ^ Lange 2012, pp. 477–9.

- ^ Payne 2015, p. 13.

- ^ a b Paul, J.; Pallath, P. (1996). Pope John Paul II and the Catholic Church in India. Mar Thoma Yogam publications. Centre for Indian Christian Archaeological Research. p. 5. Retrieved 2022-06-17.

Authors are using different names to designate the same Church : the Church of Seleucia - Ctesiphon, the Church of the East, the Babylonian Church, the Assyrian Church, or the Persian Church.

- ^ Baum & Winkler 2003, p. 3,4.

- ^ Orientalia Christiana Analecta. Pont. institutum studiorum orientalium. 1971. p. 2. Retrieved 2022-06-17.

The Church of Seleucia - Ctesiphon was called the East Syrian Church or the Church of the East .

- ^ Fiey 1994, p. 97-107.

- ^ a b c Baum & Winkler 2003, p. 4.

- ^ Baum & Winkler 2003, p. 112-123.

- ^ ISBN 9781088234327.

- ^ Procopius, Wars, I.7.1–2

* Greatrex–Lieu (2002), II, 62 - ^ Joshua the Stylite, Chronicle, XLIII

* Greatrex–Lieu (2002), II, 62 - ^ Procopius, Wars, I.9.24

* Greatrex–Lieu (2002), II, 77 - ^ a b Brock 1996, p. 23–35.

- ^ Brock 2006, p. 1-14.

- ^ Joseph 2000, p. 42.

- ^ Wood 2013, p. 140.

- ^ Moffett, Samuel H. (1992). A History of Christianity in Asia. Volume I: Beginnings to 1500. HarperCollins. p. 219.

- ISBN 978-3-643-50045-8.

- ^ Baum & Winkler 2003, p. 84-89.

- ^ The Eastern Catholic Churches 2017 Archived 2018-10-24 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved December 2010. Information sourced from Annuario Pontificio 2017 edition.

- ^ "Holy Apostolic Catholic Assyrian Church of the East — World Council of Churches". www.oikoumene.org. January 1948.

- ISBN 9780852446331.

The number of the faithful at the beginning of the twenty - first century belonging to the Assyrian Church of the East under Mar Dinkha was estimated to be around 385,000, and the number belonging to the Ancient Church of the East under Mar Addia to be 50,000-70,000.

- ^ Baum & Winkler 2003, p. 3, 30.

- ^ a b Brock, Sebastian P; Coakley, James F. "Church of the East". e-GEDSH:Gorgias Encyclopedic Dictionary of the Syriac Heritage. Retrieved 27 June 2022.

The Church of the East follows the strictly dyophysite ('two-nature') christology of Theodore of Mopsuestia, as a result of which it was misleadingly labelled as 'Nestorian' by its theological opponents.

- ^ Wilmshurst 2000.

- ^ Foltz 1999, p. 63.

- ^ Seleznyov 2010, p. 165–190.

- ^ a b c d e f "Nestorian". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved January 28, 2010.

- ^ "Nestorius". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 11 November 2018.

- ^ Kuhn 2019, p. 130.

- ^ Brock 1999, p. 286−287.

- ^ Wood 2013, p. 136.

- ^ Hilarion Alfeyev, The Spiritual World Of Isaac The Syrian (Liturgical Press 2016)

- ^ Brock 2006, p. 174.

- ^ Meyendorff 1989.

- ^ a b Baum & Winkler 2003, p. 28-29.

- ^ Payne 2009, p. 398-399.

- ^ Bethune-Baker 1908, p. 82-100.

- ^ Winkler 2003.

- ^ a b c Wilmshurst 2000, p. 4.

- ^ Brock 2006, p. 14.

- ^ Joost Jongerden, Jelle Verheij, Social Relations in Ottoman Diyarbekir, 1870-1915 (BRILL 2012), p. 21

- Gertrude Lowthian Bell, Amurath to Amurath (Heinemann 1911), p. 281

- ^ Gabriel Oussani, "The Modern Chaldeans and Nestorians, and the Study of Syriac among them" in Journal of the American Oriental Society, vol. 22 (1901), p. 81

- ^ Albrecht Classen (editor), East Meets West in the Middle Ages and Early Modern Times (Walter de Gruyter 2013), p. 704

- ^ Brock 1996, p. 23-35.

- ^ a b c Wilmshurst 2000, p. 21-22.

- ^ Foster 1939, p. 34.

- ^ Syriac Versions of the Bible by Thomas Nicol

- ^ . Retrieved 23 July 2018.

- ^ a b Baumer 2006, p. 168.

- ^ "The Shadow of Nestorius".

- ^ Kung, Tien Min (1960). 唐朝基督教之研究 [Christianity in the T'ang Dynasty] (PDF) (in Chinese (Hong Kong)). Hong Kong: The Council on Christian Literature for Overseas Chinese. p. 7 (PDF page).

佐伯博士主張此像乃景敎的耶穌像

- ^ a b Baumer 2006, p. 75, 94.

- ^ Drège 1992, p. 43, 187.

- ^ O'Daly, Briton (Yale University) (2021). "An Israel of the Seven Rivers" (PDF). Sino-Platonic Papers: 10–12.

- ^ JSTOR 41927279.

- S2CID 170249994.

- ^ Khoury, George (1997-01-22). "Eastern Christianity on the Eve of Islam". EWTN. Retrieved 2023-03-01.

- OCLC 123079516.

- JSTOR 1584359– via JSTOR.

- ^ Fiey, Jean Maurice (1970). Jalons pour une histoire de l'Église en Iraq. Louvain: Secretariat du CSCO.

- ^ Chaumont 1988.

- ^ Hill 1988, p. 105.

- ^ a b Cross & Livingstone 2005, p. 354.

- ^ Outerbridge 1952.

- ^ Baum & Winkler 2003, p. 1.

- ^ Ilaria Ramelli, "Papa bar Aggai", in Encyclopedia of Ancient Christianity, 2nd edn., 3 vols., ed. Angelo Di Berardino (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 2014), 3:47.

- ^ Fiey 1967, p. 3–22.

- ^ Roberson 1999, p. 15.

- ^ Daniel & Mahdi 2006, p. 61.

- ^ Foster 1939, p. 26-27.

- ^ Burgess & Mercier 1999, p. 9-66.

- ^ Donald Attwater & Catherine Rachel John, The Penguin Dictionary of Saints, 3rd edn. (New York: Penguin Books, 1993), 116, 245.

- ^ Tajadod 1993, p. 110–133.

- ^ Labourt 1909.

- ^ Jugie 1935, p. 5–25.

- ^ Reinink 1995, p. 77-89.

- ^ Brock 2006, p. 73.

- ^ Stewart 1928, p. 13-14.

- ^ Stewart 1928, p. 14.

- ISBN 979-10-351-0102-2

- ^ Foster 1939, p. 33.

- ^ Fiey 1993, p. 47 (Armenia), 72 (Damascus), 74 (Dailam and Gilan), 94–6 (India), 105 (China), 124 (Rai), 128–9 (Sarbaz), 128 (Samarqand and Beth Turkaye), 139 (Tibet).

- ^ Hill 1993, p. 4-5, 12.

- ISBN 9780226070803.

Neither were there any Muslims among the Ninth-Century translators. Amost all of them were Christians of various Eastern denominations: Jacobites, Melchites, and, above all, Nestorians.

- ^ Rémi Brague, Assyrians contributions to the Islamic civilization Archived 2013-09-27 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Britannica, Nestorian

- ^ Jarrett, Jonathan (2019-06-24). "When is a Nestorian not a Nestorian? Mostly, that's when". A Corner of Tenth-Century Europe. Retrieved 2023-03-01.

- ^ Ronald G. Roberson, "The Syro-Malabar Catholic Church"

- ^ "NSC NETWORK – Early references about the Apostolate of Saint Thomas in India, Records about the Indian tradition, Saint Thomas Christians & Statements by Indian Statesmen". Nasrani.net. 2007-02-16. Archived from the original on 3 April 2010. Retrieved 2010-03-31.

- .

- ISBN 978-0-300-05167-4.

- ISBN 978-90-04-44603-8.

- .

- ^ Frykenberg 2008, p. 102–107, 115.

- ^ a b Baum & Winkler 2003, p. 52.

- ^ Baum & Winkler 2003, p. 53.

- ^ "Synod of Diamper". britannica.com. Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 11 July 2022.

The local patriarch—representing the Assyrian Church of the East, to which ancient Christians in India had looked for ecclesiastical authority—was then removed from jurisdiction in India and replaced by a Portuguese bishop; the East Syrian liturgy of Addai and Mari was "purified from error"; and Latin vestments, rituals, and customs were introduced to replace the ancient traditions.

- ^ ISBN 0521243513.

Then the pope decided to throw one more stone into the pool. Apparently following a suggestion made by some among the cattanars, he sent to India four discalced Carmelites - two Italians, one Fleming and one German. These Fathers had two advantages – they were not Portuguese and they were not Jesuits. The head of the mission was given the title of apostolic commissary, and was specially charged with the duty of restoring peace in the Serra.

- ^ ISBN 978-1452528632.

- ^ "Mar Aprem Metropolitan Visits Ancient Anuradhapura Cross in Official Trip to Sri Lanka". Assyrian Church News. Archived from the original on 2015-02-26. Retrieved 6 August 2013.

- ^ Weerakoon, Rajitha (June 26, 2011). "Did Christianity exist in ancient Sri Lanka?". Sunday Times. Retrieved 2 August 2021.

- ^ "Main interest". Daily News. 22 April 2011. Archived from the original on 2015-03-29. Retrieved 2 August 2021.

- ^ Ding 2006, p. 149-162.

- ^ Stewart 1928, p. 169.

- ^ Stewart 1928, p. 183.

- ^ Moffett 1999, p. 14-15.

- ^ Jackson 2014, p. 97.

- ^ Luke 1924, p. 46–56.

- ^ Fiey 1993, p. 71.

- ^ Wilmshurst 2000, p. 66.

- ^ Wilmshurst 2000, p. 16-19.

- ^ a b Peter C. Phan, Christianities in Asia (John Wiley & Sons 2011), p. 243

- ^ Baum & Winkler 2003, p. 105.

- ^ Wilmshurst 2000, p. 345-347.

- ^ Baum & Winkler 2003, p. 104.

- ^ Wilmshurst 2000, p. 19.

- ^ Wilmshurst 2000, p. 21.

- ^ a b Wilmshurst 2000, p. 22.

- ^ Lemmens 1926, p. 17-28.

- ^ a b Fernando Filoni, The Church in Iraq CUA Press 2017), pp. 35−36

- ^ a b Habbi 1966, p. 99-132.

- ^ Patriarcha de Mozal in Syria orientali (Anton Baumstark (editor), Oriens Christianus, IV:1, Rome and Leipzig 2004, p. 277)

- ^ Assemani 1725, p. 661.

- ^ a b Wilkinson 2007, p. 86−88.

- ^ a b Wilmshurst 2000, p. 23.

- ^ Wilmshurst 2000, p. 22-23.

- ^ Tisserant 1931, p. 261-263.

- ^ Fiey 1993, p. 37.

- ^ Murre van den Berg 1999, p. 243-244.

- ^ Baum & Winkler 2003, p. 116, 174.

- ^ a b Hage 2007, p. 473.

- ^ Wilmshurst 2000, p. 22, 42 194, 260, 355.

- ^ Tisserant 1931, p. 230.

- ^ a b c d Murre van den Berg 1999, p. 252-253.

- ^ Baum & Winkler 2003, p. 114.

- ^ Wilmshurst 2000, p. 23-24.

- ^ a b Wilmshurst 2000, p. 24.

- ^ Wilmshurst 2000, p. 352.

- ^ Wilmshurst 2000, p. 24-25.

- ^ a b Wilmshurst 2000, p. 25.

- ^ Wilmshurst 2000, p. 25, 316.

- ^ Baum & Winkler 2003, p. 114, 118, 174-175.

- ^ Murre van den Berg 1999, p. 235-264.

- ^ Wilmshurst 2000, p. 24, 352.

- ^ Baum & Winkler 2003, p. 119, 174.

- ^ Wilmshurst 2000, p. 263.

- ^ Baum & Winkler 2003, p. 118, 120, 175.

- ^ Wilmshurst 2000, p. 316-319, 356.

- ^ Joseph 2000, p. 1.

- ^ Fred Aprim, "Assyria and Assyrians Since the 2003 US Occupation of Iraq"

- ^ Jakob 2014, p. 100-101.

General and cited references

- ISBN 9781604975833.

- Assemani, Giuseppe Simone (1719). Bibliotheca orientalis clementino-vaticana. Vol. 1. Roma.

- Assemani, Giuseppe Simone (1721). Bibliotheca orientalis clementino-vaticana. Vol. 2. Roma.

- Assemani, Giuseppe Simone (1725). Bibliotheca orientalis clementino-vaticana. Vol. 3. Roma.

- Assemani, Giuseppe Simone (1728). Bibliotheca orientalis clementino-vaticana. Vol. 3. Roma.

- Assemani, Giuseppe Luigi (1775). De catholicis seu patriarchis Chaldaeorum et Nestorianorum commentarius historico-chronologicus. Roma.

- Assemani, Giuseppe Luigi (2004). History of the Chaldean and Nestorian patriarchs. Piscataway, New Jersey: Gorgias Press.

- Badger, George Percy (1852). The Nestorians and Their Rituals. Vol. 1. London: Joseph Masters.

- ISBN 9780790544823.

- ISBN 9781134430192.

- Baumer, Christoph (2006). The Church of the East: An Illustrated History of Assyrian Christianity. London-New York: Tauris. ISBN 9781845111151.

- Becchetti, Filippo Angelico (1796). Istoria degli ultimi quattro secoli della Chiesa. Vol. 10. Roma.

- ISBN 9788872102626.

- ISBN 9781107432987.

- Bevan, George A. (2009). "The Last Days of Nestorius in the Syriac Sources". Journal of the Canadian Society for Syriac Studies. 7 (2007): 39–54. ISBN 9781463216153.

- Bevan, George A. (2013). "Interpolations in the Syriac Translation of Nestorius' Liber Heraclidis". Studia Patristica. 68: 31–39.

- Binns, John (2002). An Introduction to the Christian Orthodox Churches. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521667388.

- ISBN 9780860783053.

- .

- ISBN 9780815330714.

- ISBN 9780754659082.

- Brock, Sebastian P. (2007). "Early Dated Manuscripts of the Church of the East, 7th-13th Century". Journal of Assyrian Academic Studies. 21 (2): 8–34. Archived from the originalon 2008-10-06.

- Burgess, Stanley M. (1989). The Holy Spirit: Eastern Christian Traditions. Peabody, Mass.: Hendrickson Publishers. ISBN 9780913573815.

- Burgess, Richard W.; Mercier, Raymond (1999). "The Dates of the Martyrdom of Simeon bar Sabba'e and the 'Great Massacre'". Analecta Bollandiana. 117 (1–2): 9–66. .

- Burleson, Samuel; Rompay, Lucas van (2011). "List of Patriarchs of the Main Syriac Churches in the Middle East". Gorgias Encyclopedic Dictionary of the Syriac Heritage. Piscataway, NJ: Gorgias Press. pp. 481–491.

- Carlson, Thomas A. (2017). "Syriac Christology and Christian Community in the Fifteenth-Century Church of the East". Syriac in its Multi-Cultural Context. Leuven: Peeters Publishers. pp. 265–276. ISBN 9789042931640.

- Chabot, Jean-Baptiste (1902). Synodicon orientale ou recueil de synodes nestoriens (PDF). Paris: Imprimerie Nationale.

- Chapman, John (1911). "Nestorius and Nestorianism". The Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 10. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- Chaumont, Marie-Louise (1964). "Les Sassanides et la christianisation de l'Empire iranien au IIIe siècle de notre ère". Revue de l'histoire des religions. 165 (2): 165–202. .

- Chaumont, Marie-Louise (1988). La Christianisation de l'Empire Iranien: Des origines aux grandes persécutions du ive siècle. Louvain: Peeters. ISBN 9789042905405.

- Chesnut, Roberta C. (1978). "The Two Prosopa in Nestorius' Bazaar of Heracleides". The Journal of Theological Studies. 29 (29): 392–409. JSTOR 23958267.

- Coakley, James F. (1992). The Church of the East and the Church of England: A History of the Archbishop of Canterbury's Assyrian Mission. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 9780198267447.

- Coakley, James F. (1996). "The church of the East since 1914". The Bulletin of the John Rylands Library. 78 (3): 179–198. .

- Coakley, James F. (2001). Mar Elia Aboona und the history of the East Syrian patriarchate. Vol. 85. Harrassowitz. pp. 119–138. ISBN 9783447042871.

- Cross, Frank L.; Livingstone, Elizabeth A., eds. (2005). Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church (3rd revised ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780192802903.

- Daniel, Elton L.; Mahdi, Ali Akbar (2006). Culture and customs of Iran. Greenwood Press. ISBN 9780313320538.

- Ding, Wang (2006). "Remnants of Christianity from Chinese Central Asia in Medieval Ages". In Malek, Roman; Hofrichter, Peter L. (eds.). Jingjiao: The Church of the East in China and Central Asia. Institut Monumenta Serica. pp. 149–162. ISBN 9783805005340.

- OCLC 1024004171.

- Ebeid, Bishara (2016). "The Christology of the Church of the East: An Analysis of Christological Statements and Professions of Faith of the Official Synods of the Church of the East before A. D. 612". Orientalia Christiana Periodica. 82 (2): 353–402.

- Ebeid, Bishara (2017). "Christology and Deification in the Church of the East: Mar Gewargis I, His Synod and His Letter to Mina as a Polemic against Martyrius-Sahdona". Cristianesimo Nella Storia. 38 (3): 729–784.

- Fiey, Jean Maurice (1967). "Les étapes de la prise de conscience de son identité patriarcale par l'Église syrienne orientale". L'Orient Syrien. 12: 3–22.

- Fiey, Jean Maurice (1970a). Jalons pour une histoire de l'Église en Iraq. Louvain: Secretariat du CSCO.

- Fiey, Jean Maurice (1970b). "L'Élam, la première des métropoles ecclésiastiques syriennes orientales" (PDF). Parole de l'Orient. 1 (1): 123–153. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2021-06-19. Retrieved 2018-08-18.

- Fiey, Jean Maurice (1970c). "Médie chrétienne" (PDF). Parole de l'Orient. 1 (2): 357–384. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2021-06-19. Retrieved 2018-08-18.

- ISBN 9780860780519.

- ISBN 9783515057189.

- ISBN 9783515057189.

- ISBN 9780813229652.

- ISBN 9780312233389.

- Foster, John (1939). The Church of the T'ang Dynasty. London: Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge.

- Frazee, Charles A. (2006) [1983]. Catholics and Sultans: The Church and the Ottoman Empire 1453-1923. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521027007.

- Frykenberg, Robert Eric (2008). Christianity in India: From Beginnings to the Present. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780198263777.

- Giamil, Samuel (1902). Genuinae relationes inter Sedem Apostolicam et Assyriorum orientalium seu Chaldaeorum ecclesiam. Roma: Ermanno Loescher.

- ISBN 9780199212880.

- Gulik, Wilhelm van (1904). "Die Konsistorialakten über die Begründung des uniert-chaldäischen Patriarchates von Mosul unter Papst Julius III" (PDF). Oriens Christianus. 4: 261–277.

- Гумилёв, Лев Николаевич (1970). Поиски вымышленного царства: Легенда о государстве пресвитера Иоанна[Searching for an Imaginary Kingdom: The Legend of the Kingdom of Prester John] (in Russian). Москва: Наука.

- Habbi, Joseph (1966). "Signification de l'union chaldéenne de Mar Sulaqa avec Rome en 1553". L'Orient Syrien. 11: 99–132, 199–230.

- Habbi, Joseph (1971a). "L'unification de la hiérarchie chaldéenne dans la première moitié du XIXe siècle" (PDF). Parole de l'Orient. 2 (1): 121–143. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2021-06-19. Retrieved 2017-08-14.

- Habbi, Joseph (1971b). "L'unification de la hiérarchie chaldéenne dans la première moitié du XIXe siècle (Suite)" (PDF). Parole de l'Orient. 2 (2): 305–327. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2021-06-19. Retrieved 2017-08-14.

- Hage, Wolfgang (2007). Das orientalische Christentum. Stuttgart: ISBN 9783170176683.

- Harrak, Amir (2003). "Patriarchal Funerary Inscriptions in the Monastery of Rabban Hormizd: Types, Literary Origins, and Purpose" (PDF). Hugoye: Journal of Syriac Studies. 6 (2): 235–264.

- Hauser, Stefan R. (2019). "The Church of the East until the Eighth Century". The Oxford Handbook of Early Christian Archaeology. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 431–450. ISBN 9780199369041.

- Herman, Geoffrey (2019). "The Syriac World in the Persian Empire". The Syriac World. London: Routledge. pp. 134–145.

- ISBN 9780748604555.

- Hill, Henry, ed. (1988). Light from the East: A Symposium on the Oriental Orthodox and Assyrian Churches. Toronto: Anglican Book Centre. ISBN 9780919891906.

- ISBN 9781725202399.

- Hunter, Erica (1996). "The church of the East in central Asia". The Bulletin of the John Rylands Library. 78 (3): 129–142. S2CID 161756931.

- ISBN 9781317878995.

- Jakob, Joachim (2014). Ostsyrische Christen und Kurden im Osmanischen Reich des 19. und frühen 20. Jahrhunderts. Münster: LIT Verlag. ISBN 9783643506160.

- ISBN 9780061472800.

- ISBN 9004116419.

- Jugie, Martin (1935). "L'ecclésiologie des Nestoriens". Échos d'Orient. 34 (177): 5–25. .

- Kitchen, Robert A. (2012). "The Syriac Tradition". The Orthodox Christian World. London-New York: Routledge. pp. 66–77. ISBN 9781136314841.

- Klein, Wassilios (2000). Das nestorianische Christentum an den Handelswegen durch Kyrgyzstan bis zum 14. Jh. Turnhout: Brepols Publishers. ISBN 9782503510354.

- Kuhn, Michael F. (2019). God is One: A Christian Defence of Divine Unity in the Muslim Golden Age. Carlisle: Langham Publishing. ISBN 9781783685776.

- Labourt, Jérôme (1908). "Note sur les schismes de l'Église nestorienne, du XVIe au XIXe siècle". Journal Asiatique. 11: 227–235.

- Labourt, Jérôme (1909). "St. Ephraem". The Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 5. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- Lampart, Albert (1966). Ein Märtyrer der Union mit Rom: Joseph I. 1681–1696, Patriarch der Chaldäer. Einsiedeln: Benziger Verlag.

- Lange, Christian (2012). Mia energeia: Untersuchungen zur Einigungspolitik des Kaisers Heraclius und des Patriarchen Sergius von Constantinopel. Mohr Siebeck. ISBN 9783161509674.

- Lemmens, Leonhard (1926). "Relationes nationem Chaldaeorum inter et Custodiam Terrae Sanctae (1551-1629)". Archivum Franciscanum Historicum. 19: 17–28.

- Luke, Harry Charles (1924). "The Christian Communities in the Holy Sepulchre" (PDF). In Ashbee, Charles Robert (ed.). Jerusalem 1920-1922: Being the Records of the Pro-Jerusalem Council during the First Two Years of the Civil Administratio. London: John Murray. pp. 46–56.

- Marthaler, Berard L., ed. (2003). "Chaldean Catholic Church (Eastern Catholic)". The New Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 3. Thompson-Gale. pp. 366–369.[permanent dead link]

- Menze, Volker L. (2019). "The Establishment of the Syriac Churches". The Syriac World. London: Routledge. pp. 105–118. ISBN 9781138899018.

- ISBN 978-0-88-141056-3.

- Moffett, Samuel Hugh (1999). "Alopen". Biographical Dictionary of Christian Missions. William. B. Eerdmans Publishing Company. pp. 14–15. ISBN 9780802846808.

- Mooken, Aprem (1976). The Nestorian Fathers. Trichur: Mar Narsai Press.

- Mooken, Aprem (1976). Nestorian Missions. Trichur: Mar Narsai Press.

- Morgan, David (1986). The Mongols. Basil Blackwell. ISBN 9780631135562.

- Moule, Arthur C. (1930). Christians in China before the year 1550. London: Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge.

- .

- Murre van den Berg, Heleen (2008). "Classical Syriac, Neo-Aramaic, and Arabic in the Church of the East and the Chaldean Church between 1500 and 1800". Aramaic in Its Historical and Linguistic Setting. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag. pp. 335–352. ISBN 9783447057875.

- Murre van den Berg, Heleen (2005). "The Church of the East in the Sixteenth to the Eighteenth Century: World Church or Ethnic Community?". Redefining Christian Identity: Cultural Interaction in the Middle East since the Rise of Islam. Leuven: Peeters Publishers. pp. 301–320. ISBN 9789042914186.

- ISBN 9781586172824.

- O'Mahony, Anthony (2006). "Syriac Christianity in the modern Middle East". In ISBN 9780521811132.

- Outerbridge, Leonard M. (1952). The Lost Churches of China. Philadelphia: Westminster Press.

- Payne, Richard E. (2009). "Persecuting Heresy in Early Islamic Iraq: The Catholicos Ishoyahb III and the Elites of Nisibis". The Power of Religion in Late Antiquity. Farnham: Ashgate. pp. 397–409. ISBN 9780754667254.

- Payne, Richard E. (2015). A State of Mixture: Christians, Zoroastrians, and Iranian Political Culture in Late Antiquity. Oakland: University of California Press. ISBN 9780520292451.

- Penn, Michael Philip (2019). "Early Syriac Reactions to the Rise of Islam". The Syriac World. London: Routledge. pp. 175–188. ISBN 9781138899018.

- Pirtea, Adrian C. (2019). "The Mysticism of the Church of the East". The Syriac World. London: Routledge. pp. 355–376. ISBN 9781138899018.

- Reinink, Gerrit J. (1995). "Edessa Grew Dim and Nisibis Shone Forth: The School of Nisibis at the Transition of the Sixth-Seventh Century". Centres of Learning: Learning and Location in Pre-modern Europe and the Near East. Leiden: Brill. pp. 77–89. ISBN 9004101934.

- Reinink, Gerrit J. (2009). "Tradition and the Formation of the 'Nestorian' Identity in Sixth- to Seventh-Century Iraq". Church History and Religious Culture. 89 (1–3): 217–250. JSTOR 23932289.

- Roberson, Ronald (1999) [1986]. The Eastern Christian Churches: A Brief Survey (6th ed.). Roma: Orientalia Christiana. ISBN 9788872103210.

- Rossabi, Morris (1992). Voyager from Xanadu: Rabban Sauma and the First Journey from China to the West. Kodansha International. ISBN 9784770016508.

- Rücker, Adolf (1920). "Über einige nestorianische Liederhandschriften, vornehmlich der griech. Patriarchatsbibliothek in Jerusalem" (PDF). Oriens Christianus. 9: 107–123.

- Saeki, Peter Yoshiro (1937). The Nestorian Documents and Relics in China. Tokyo: Academy of oriental culture.

- Seleznyov, Nikolai N. (2008). "The Church of the East & Its Theology: History of Studies". Orientalia Christiana Periodica. 74 (1): 115–131.

- Seleznyov, Nikolai N. (2010). "Nestorius of Constantinople: Condemnation, Suppression, Veneration: With special reference to the role of his name in East-Syriac Christianity". Journal of Eastern Christian Studies. 62 (3–4): 165–190.

- Silverberg, Robert (1972). The Realm of Prester John. Garden City, NY: Doubleday.

- Spuler, Bertold (1961). "Die Nestorianische Kirche". Religionsgeschichte des Orients in der Zeit der Weltreligionen. Leiden: Brill. pp. 120–169. ISBN 9789004293816.

- Stewart, John (1928). Nestorian Missionary Enterprise: A Church on Fire. Edinburgh: T. & T. Clark.

- Tajadod, Nahal (1993). Les Porteurs de lumière: Péripéties de l'Eglise chrétienne de Perse, IIIe-VIIe siècle. Paris: Plon.

- Taylor, David G. K. (2019). "The Coming of Christianity to Mesopotamia". The Syriac World. London: Routledge. pp. 68–87. ISBN 9781138899018.

- Tfinkdji, Joseph (1914). "L' église chaldéenne catholique autrefois et aujourd'hui". Annuaire Pontifical Catholique. 17: 449–525.

- Tisserant, Eugène (1931). "L'Église nestorienne". Dictionnaire de théologie catholique. Vol. 11. Paris: Letouzey et Ané. pp. 157–323.

- Vine, Aubrey R. (1937). The Nestorian Churches. London: Independent Press. ISBN 9780404161880.

- Vosté, Jacques Marie (1925). "Missio duorum fratrum Melitensium O. P. in Orientem saec. XVI et relatio, nunc primum edita, eorum quae in istis regionibus gesserunt". Analecta Ordinis Praedicatorum. 33 (4): 261–278.

- Vosté, Jacques Marie (1928). "Catalogue de la bibliothèque syro-chaldéenne du couvent de Notre-Dame des Semences près d'Alqoš (Iraq)". Angelicum. 5: 3–36, 161–194, 325–358, 481–498.

- Vosté, Jacques Marie (1930). "Les inscriptions de Rabban Hormizd et de N.-D. des Semences près d'Alqoš (Iraq)". Le Muséon. 43: 263–316.

- Vosté, Jacques Marie (1931). "Mar Iohannan Soulaqa, premier Patriarche des Chaldéens, martyr de l'union avec Rome (†1555)". Angelicum. 8: 187–234.

- ISBN 9780837080789.

- Wigram, William Ainger (1929). The Assyrians and Their Neighbours. London: G. Bell & Sons.

- Williams, Daniel H. (2013). "The Evolution of Pro-Nicene Theology in the Church of the East". From the Oxus River to the Chinese Shores: Studies on East Syriac Christianity in China and Central Asia. Münster: LIT Verlag. pp. 387–395. ISBN 9783643903297.

- Wilkinson, Robert J. (2007). Orientalism, Aramaic, and Kabbalah in the Catholic Reformation: The First Printing of the Syriac New Testament. Leiden-Boston: Brill. ISBN 9789004162501.

- Wilmshurst, David (2000). The Ecclesiastical Organisation of the Church of the East, 1318–1913. Louvain: Peeters Publishers. ISBN 9789042908765.

- Wilmshurst, David (2011). The Martyred Church: A History of the Church of the East. London: East & West Publishing Limited. ISBN 9781907318047.

- Wilmshurst, David (2019a). "The Church of the East in the 'Abbasid Era". The Syriac World. London: Routledge. pp. 189–201. ISBN 9781138899018.

- Wilmshurst, David (2019b). "The patriarchs of the Church of the East". The Syriac World. London: Routledge. pp. 799–805. ISBN 9781138899018.

- ISBN 382586796X.

- Wood, Philip (2013). The Chronicle of Seert: Christian Historical Imagination in Late Antique Iraq. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199670673.

![The Grigorovskoye Plate: Paten with biblical scenes in medallions, counterclockwise from bottom left: women at the empty tomb, the crucifixion, and the Ascension. Semirechye, 9th–10th century.[64]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/7/76/Dish_with_biblical_scenes%2C_Church_of_the_East%2C_line_drawing.jpg/225px-Dish_with_biblical_scenes%2C_Church_of_the_East%2C_line_drawing.jpg)