Cinderella (Ashton)

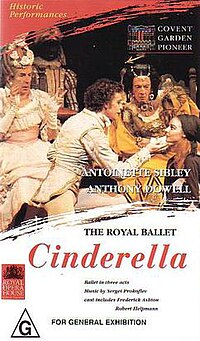

Antoinette Sibley as Cinderella and Anthony Dowell as The Prince, with Frederick Ashton and Robert Helpmann as the two Ugly Stepsisters (VHS cover).

This version of the Cinderella ballet, using Sergei Prokofiev's Cinderella music and re-choreographed by Frederick Ashton, is a comic ballet.

Ballet productions

| Choreography | Frederick Ashton |

| Music | Sergei Prokofiev |

| Design | Jean-Denis Malcles (scenery and costumes) |

| Libretto | Frederick Ashton (after the fairy tale by Charles Perrault) |

| First production | Sadler's Wells Ballet, Royal Opera House , London, 23 December 1948

|

| Principal dancers | Moira Shearer (Cinderella), Michael Somes (Prince), Frederick Ashton and Robert Helpmann (Stepsisters), Alexander Grant (The Jester) |

| Other productions | Royal Ballet (new production, restaged and revised by Frederick Ashton); with Margot Fonteyn (Cinderella), David Blair (Prince), Frederick Ashton and Robert Helpmann (Ugly Stepsisters); London, 23 December 1965

|

| First US production | Auditorium Theatre, Chicago, October 2006[1]

|

| Other choreographic treatments of the story | François Albert Decombe (London, 1822); St. Petersburg, 1893) see Cinderella (Fitinhof-Schell)

|

Plot outline

Ashton's Cinderella is his own realised dream of a Petipa ballet and the ballet itself enacts the realisation of dreams, notably Cinderella's own. When we first see her she is a demi-caractere dancer dreaming of being a

Origins

There are many versions of the story of Cinderella (the earliest was written down in

The earliest Cinderella ballet proper was by Duport in Vienna in 1813, although Drury Lane's Cinderella ten years earlier had a ballet divertissement of Loves and Graces introduced by Venus.

London's first complete Cinderella ballet was seen in 1822, the year Paris first heard Rossini's opera La Cenerentola.

Marius Petipa, Lev Ivanov, and Enrico Cecchetti choreographed

Adeline Genée first danced Cinderella at the Empire, Leicester Square, on Twelfth Night 1906, and 29 years later to the day Andrée Howard choreographed her one-act Cinderella (in which Frederick Ashton was the elegant Prince) for Rambert's Ballet Club at the Mercury Theatre, Notting Hill Gate.

The score

Sergei Prokofiev had begun composition on the score for Cinderella in 1941 but, because of the war and his opera

The music was choreographed first for the

Prokofiev and his collaborators were guided by Perrault's version of the story and by the great Tchaikovsky ballet scores, which themselves served the structure of Petipa's choreography. Prokofiev wrote that he conceived Cinderella (which he dedicated to Tchaikovsky):

... as a classical ballet with variations, adagois, pas de deux, etc... I see Cinderella not only as a fairy-tale character but also as a real person, feeling, experiencing, and moving among us,

and again:

What I wished to express above all in the music of Cinderella was the poetic love of Cinderella and the Prince, the birth and flowering of that love, the obstacles in its path and finally the dream fulfilled.

Ashton's choreography

Frederick Ashton first considered the idea of composing a full-evening ballet as early as 1939, when the

Early in 1946, though, in a speech at the Soviet Theater Exhibition,

He had heard and liked quite a lot of the Prokofiev music and he thought Perrault's story a good one. In the event, Ashton cut some of the music, notably the third-act scene showing the Prince's journey in search of Cinderella (a pretext for a divertissement of national dances: Ashton's comment on this was "I didn't like any of the places he went to, nor the music he wrote for them") and a shorter dance of Grasshoppers and Dragonflies after the Fairy Summer's variation in the first act. The choreography of Cinderella is Ashton's homage to the classical tradition of Petipa, as had been Symphonic Variations of two years earlier, albeit on a smaller scale. In 1948 Ashton also created Scènes de ballet, which distilled the essence of Petipa's ballets down to just one act.

The choreography of Cinderella is full of dreams, some most definitely unfulfilled. In the ballroom, the put-upon, shy Ugly Sister—significantly Ashton's own role—performs a Petipa figure that amounts to her dream of being Odile at Siegfried's ball or the

References

- ^ Vivien Schweitzer, "Joffrey Ballet First US Company to Perform Frederick Ashton's Cinderella", Playbill Arts, 29 September 2006.

Sources

- Bremster, M. (1993). International Dictionary of Ballet (Vol. 1 and 2). Detroit: St James Press. ISBN 1-55862-084-2