Civic Center, San Francisco

Civic Center

UN Plaza | ||

|---|---|---|

ZIP codes 94102, 94109 | ||

| Area codes | 415/628 | |

| [3] | ||

San Francisco Civic Center Historic District | ||

San Francisco, California | ||

| Area | 45.6 acres (18.5 ha) | |

| Built | 1912[5] | |

| Architectural style | Late 19th and 20th Century revivals Beaux-Arts | |

| NRHP reference No. | 78000757[4] | |

| Significant dates | ||

| Added to NRHP | October 10, 1978[4] | |

| Designated NHLD | February 27, 1987[6] | |

The Civic Center in

Location

The Civic Center is bounded by

History

The first permanent San Francisco City Hall was completed in 1898 on a triangular-shaped plot in what later became Civic Center, bounded by Larkin, McAllister, and Market, after a protracted construction effort that had started in 1871; although the constructors had promised to complete work within two years, "honest graft" was an accepted practice, and the cost of the structure ballooned from $1 million as budgeted to $8 million.[7]: 170

The Civic Center was built in the early 20th century after the earlier City Hall was destroyed in the 1906 earthquake and fire. Although the architect and urban planner Daniel Burnham had provided the city with plans for a neo-classical Civic Center shortly before the 1906 earthquake,[8] his plans were never carried out. Burnham's plan called for a large semi-circular plaza at the intersection of Market and Van Ness as a hub linking official buildings along spoked streets.[9]: 10–11

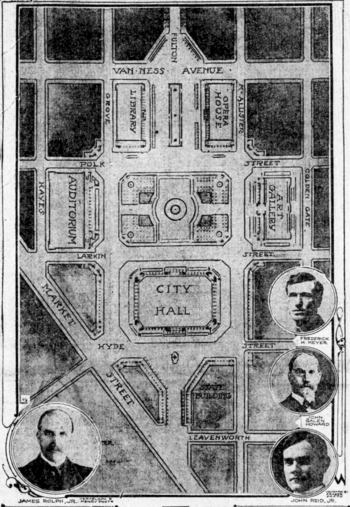

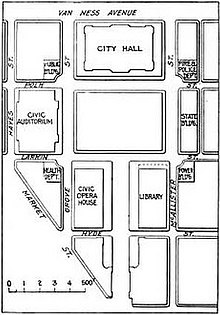

Following the earthquake, a temporary city hall was established on Market Street, but planning for a permanent structure and civic center did not take place for several years. The current Civic Center was planned by a group of local architects, chaired by John Galen Howard.[7] The new Civic Center would consist of five main buildings facing a central rectangular plaza: City Hall, Auditorium, Main Library, Opera House, and State Office Building.[9]: 12 A bond was issued on March 29, 1912, for $8.8 million to carry out the construction of the new Civic Center; at the time, the city only owned the triangular-shaped plot where the old City Hall had stood prior to the earthquake.[10] A resolution passed by the San Francisco Board of Supervisors required the new City Hall to be built on the site of the old City Hall, so early plans for Civic Center showed City Hall east of the central plaza. Opinions solicited by the consulting architectural team led to the relocation of City Hall to the west side of the plaza.[9]: 12 Ground was broken for City Hall, the first building in the new Civic Center, on April 5, 1913.[11][10]

The current City Hall was completed in 1915, in time for the Panama–Pacific International Exposition. The second building to be started was Exposition Auditorium; at the time, plans included a new Main Library (to be built on the site of the old City Hall) but left the former Marshall Square (bounded by Larkin, Fulton, Hyde, and Grove) undeveloped.[10] Plans for a new opera house on Marshall Square had been dropped[10] The Main Library (1916), the California State Building (1926), War Memorial Opera House and its neighboring twin, the War Memorial Veterans Building (which together were the nucleus of the San Francisco War Memorial and Performing Arts Center, completed in 1932), and the Old Federal Building (1936) were all completed after the Exposition. Civic Center Plaza was established by 1915, but not completed until 1925. Marshall Square remained undeveloped[9]: 12, 14 until the new Main Library was constructed there in the early 1990s.

During

Its central location, vast open space, and the collection of government buildings have made and continue to make Civic Center the scene of massive political rallies. It has been the scene of massive

Attractions and characteristics

- Government

- Monuments

- Culture

- Parks and open spaces

- Transit stops

- Education

Government center

The centerpiece of the Civic Center is the

North of City Hall is the

Monuments

The

Culture

West of City Hall on Van Ness Avenue is the

Parks and open spaces

The main open space just east of City Hall is

Renovated and re-opened on February 15, 2018, the Helen Diller Civic Center Playgrounds reside on the Northeast and Southeast corners of the Civic Center Plaza.

Transit

Access to Civic Center is provided by the

Education

Civic Center is the site of four famous higher education schools:

Other points of interest

The Fox Plaza condominium complex is also located nearby. The large art installation Firefly by Ned Kahn can be seen on the side of the San Francisco Public Utilities Commission building on Golden Gate Avenue.

In December 2010, a set of innovative wind and solar hybrid streetlamps provided by

Selected photos

-

Ronald M. George State Office Complex: Earl Warren Building with the Hiram W. Johnson State Office Building behind

-

Asian Art Museum

-

War Memorial Opera House

See also

- 49-Mile Scenic Drive

- Bernard J.S. Cahill

References

- ^ a b "Statewide Database". UC Regents. Archived from the original on February 1, 2015. Retrieved December 8, 2014.

- ^ "California's 11th Congressional District - Representatives & District Map". Civic Impulse, LLC.

- ^ a b c "Civic Center neighborhood in San Francisco, California (CA), 94102, 94109 subdivision profile - real estate, apartments, condos, homes, community, population, jobs, income, streets".

- ^ a b c "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. July 9, 2010.

- ^ a b Charleton, James P. (November 9, 1984). "San Francisco Civic Center" (pdf). National Register of Historic Places – Inventory Nomination Form. National Park Service. Retrieved May 20, 2012.

- ^ a b "San Francisco Civic Center". National Historic Landmark Quicklinks. National Park Service. Archived from the original on October 8, 2012. Retrieved March 20, 2012.

- ^ ISBN 0-520-05263-3. Retrieved October 26, 2018.

- ^ Burnham, Daniel H.; Bennett, Edward H. (September 1905). O'Day, Edward F. (ed.). Report on a plan for San Francisco (Report). Association for the Improvement and Adornment of San Francisco. Retrieved January 31, 2017.

- ^ a b c d Civic Center Proposal (PDF) (Report). City and County of San Francisco, Office of Mayor Dianne Feinstein. November 1987. Retrieved October 26, 2018.

- ^ a b c d "Civic Center at San Francisco". Engineering Record: 489. October 31, 1914. Retrieved October 26, 2018.

- ^ "Now for New City Hall". San Francisco Call. April 5, 1913. Retrieved October 26, 2018.

- ^ "San Francisco Division." Federal Bureau of Investigation. Retrieved on June 9, 2015. "450 Golden Gate Avenue, 13th Floor San Francisco, CA 94102-9523"

- ^ 2.6 acres, 1975, part of BART construction, Halprin as designer Archived 2007-09-27 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b "$10 million playgrounds give downtown SF kids a safe place to frolic". SFChronicle.com. February 16, 2018. Retrieved August 1, 2018.

- ^ a b c "Helen Diller Playgrounds at Civic Center Improvements | San Francisco Recreation and Park". sfrecpark.org. Retrieved August 1, 2018.

- ^ "Helen Diller Civic Center Playgrounds". The Trust for Public Land. Retrieved August 1, 2018.

- ^ "Academy of Art University Campus Map" (PDF). academyart.edu. Academy of Art University. Retrieved November 23, 2016.

- ^ Hybrid Street Lamp Hits San Francisco Archived 2010-12-20 at the Wayback Machine

External links

- Photo tour of Civic Center A photo tour of Civic Center complete with narrative text.

- "San Francisco Civic Center" (pdf). Photographs. National Park Service. Retrieved May 20, 2012.

- The architects

- Earth Day SF San Francisco's very well attended Earth Day celebration.

- "City Hall and Civic Center History". San Francisco Municipal Reports. San Francisco Board of Supervisors: 977–1014. 1918. Retrieved October 26, 2018.