Ancient philosophy

This article needs additional citations for verification. (October 2011) |

| Part of a series on |

| Philosophy |

|---|

This page lists some links to ancient philosophy, namely

Overview

Genuine philosophical thought, depending upon original individual insights, arose in many cultures roughly contemporaneously. Karl Jaspers termed the intense period of philosophical development beginning around the 7th century BCE and concluding around the 3rd century BCE an Axial Age in human thought.

In Western philosophy, the spread of Christianity in the Roman Empire marked the ending of Hellenistic philosophy and ushered in the beginnings of medieval philosophy, whereas in the Middle East, the spread of Islam through the Arab Empire marked the end of Old Iranian philosophy and ushered in the beginnings of early Islamic philosophy.

Ancient Greek and Roman philosophy

Philosophers

Pre-Socratic philosophers

- Milesian School

- Thales(624 – c 546 BCE)

- Anaximander (610 – 546 BCE)

- Anaximenes of Miletus (c. 585 – c. 525 BCE)

- Pythagoras (582 – 496 BCE)

- Philolaus (470 – 380 BCE)

- Alcmaeon of Croton

- Archytas (428 – 347 BCE)

- Heraclitus (535 – 475 BCE)

- Eleatic School

- Xenophanes (570 – 470 BCE)

- Parmenides (510 – 440 BCE)

- Zeno of Elea (490 – 430 BCE)

- Melissus of Samos (c. 470 BCE – ?)

- Pluralists

- Empedocles (490 – 430 BCE)

- Anaxagoras (500 – 428 BCE)

- Leucippus (first half of 5th century BCE)

- Democritus (460 – 370 BCE)

- Metrodorus of Chios (4th century BCE)

- Pherecydes of Syros (6th century BCE)

- Sophists

- Protagoras (490 – 420 BCE)

- Gorgias (487 – 376 BCE)

- Antiphon(480 – 411 BCE)

- Prodicus (465/450 – after 399 BCE)

- Hippias (middle of the 5th century BCE)

- Thrasymachus (459 – 400 BCE)

- Callicles

- Critias

- Lycophron

- Diogenes of Apollonia (c. 460 BCE – ?)

Classical Greek philosophers

- Socrates (469 – 399 BCE)

- Euclid of Megara (450 – 380 BCE)

- Antisthenes (445 – 360 BCE)

- Aristippus (435 – 356 BCE)

- Plato (428 – 347 BCE)

- Speusippus (407 – 339 BCE)

- Diogenes of Sinope(400 – 325 BCE)

- Xenocrates (396 – 314 BCE)

- Aristotle (384 – 322 BCE)

- Stilpo (380 – 300 BCE)

- Theophrastus (370 – 288 BCE)

Hellenistic philosophy

- Pyrrho (365 – 275 BCE)

- Epicurus (341 – 270 BCE)

- Metrodorus of Lampsacus (the younger) (331 – 278 BCE)

- Zeno of Citium (333 – 263 BCE)

- Cleanthes (c. 330 – c. 230 BCE)

- Timon(320 – 230 BCE)

- Arcesilaus (316 – 232 BCE)

- Menippus (3rd century BCE)

- Archimedes (c. 287 – 212 BCE)

- Chrysippus (280 – 207 BCE)

- Carneades (214 – 129 BCE)

- Clitomachus (187 – 109 BCE)

- Metrodorus of Stratonicea (late 2nd century BCE)

- Philo of Larissa (160 – 80 BCE)

- Posidonius (135 – 51 BCE)

- Antiochus of Ascalon (130 – 68 BCE)

- Aenesidemus (1st century BCE)

- Agrippa(1st century CE)

Hellenistic schools of thought

- Academic skepticism

- Cynicism

- Cyrenaicism

- Eclecticism

- Epicureanism

- Middle Platonism

- Neo-Platonism

- Neopythagoreanism

- Peripatetic School

- Pyrrhonism

- Stoicism

- Sophism

Early Roman and Christian philosophy

See also: Christian philosophy

Philosophers during Roman times

- Cicero (106 – 43 BCE)

- Lucretius (94 – 55 BCE)

- Seneca (4 BCE – 65 CE)

- Musonius Rufus(30 – 100 CE)

- Plutarch (45 – 120 CE)

- Epictetus (55 – 135 CE)

- Favorinus (c. 80 – c. 160 CE)

- Marcus Aurelius (121 – 180 CE)

- Clement of Alexandria (150 – 215 CE)

- Alcinous (philosopher) (2nd century CE)

- Sextus Empiricus (3rd century CE)

- Alexander of Aphrodisias (3rd century CE)

- Ammonius Saccas (3rd century CE)

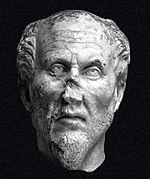

- Plotinus (205 – 270 CE)

- Porphyry (232 – 304 CE)

- Iamblichus (242 – 327 CE)

- Themistius (317 – 388 CE)

- Ambrose (340 – 397 CE)

- Augustine of Hippo (354 – 430 CE)

- Proclus (411 – 485 CE)

- Damascius (462 – 540 CE)

- Boethius(472 – 524 CE)

- Simplicius of Cilicia (490 – 560 CE)

- John Philoponus (490 – 570 CE)

Ancient Iranian philosophy

See also:

While there are ancient relations between the Indian

Schools of thought

Ideas and tenets of Zoroastrian schools of Early Persian philosophy are part of many works written in

Zoroastrianism

- Zarathustra

- Jamasp

- Ostanes

- Mardan-Farrux Ohrmazddadan[4]

- Adurfarnbag Farroxzadan[5]

- Adurbad Emedan[5]

- Avesta

- Gathas

Pre-Manichaean thought

Manichaeism

Mazdakism

- Mazdak the Elder[9]

- Mazdak (died c. 524 or 528 CE)

Zurvanism

Philosophy and the Empire

- Political philosophy

- University of Gundishapur

- Borzouye

- Bakhtshooa Gondishapuri

- philosophical discourses

Literature

- Pahlavi literature

Ancient Jewish philosophy

See also: Jewish philosophy

- Hillel the Elder (c. 110 BCE – 10CE)

- Philo of Alexandria(30 BCE – 45 CE)

- Rabbi Akiva (c. 40 – c. 137 CE)

Ancient Indian philosophy

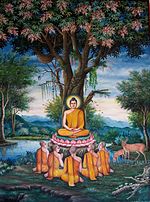

The ancient Indian philosophy is a fusion of two ancient traditions: the Vedic tradition and the śramaṇa tradition.

Vedic philosophy

Indian philosophy begins with the

- "Whence all creation had its origin,

- he, whether he fashioned it or whether he did not,

- he, who surveys it all from highest heaven,

- he knows—or maybe even he does not know."

In the Vedic view, creation is ascribed to the self-consciousness of the primeval being (Purusha). This leads to the inquiry into the one being that underlies the diversity of empirical phenomena and the origin of all things. Cosmic order is termed rta and causal law by karma. Nature (prakriti) is taken to have three qualities (sattva, rajas, and tamas).

Sramana philosophy

Classical Indian philosophy

In classical times, these inquiries were systematized in six schools of philosophy. Some of the questions asked were:

- What is the ontological nature of consciousness?

- How is cognition itself experienced?

- Is mind (chit) intentional or not?

- Does cognition have its own structure?

The six schools of Indian philosophy are:

- Nyaya

- Vaisheshika

- Samkhya

- Yoga

- Mimamsa(Purva Mimamsa)

- Vedanta (Uttara Mimamsa)

Ancient Indian philosophers

1st millennium BCE

- Parashara – writer of Viṣṇu Purāṇa.

Philosophers of Vedic Age (c. 1500 – c. 600 BCE)

- Rishi Narayana – seer of the Purusha Sukta of the Rig Veda.[10]

- Seven Rishis – Atri, Bharadwaja, Gautama, Jamadagni, Kasyapa, Vasishtha, Viswamitra.[11]

- Other Vedic Rishis – Gritsamada, Sandilya, Kanva etc.

- , as accredited by later followers.

- Vedic sages, greatly influenced Buddhisticthought.

- Lopamudra

- Gargi Vachaknavi

- Maitreyi

- Parshvanatha

- Ghosha

- Atharva Veda and author of Mundaka Upanishad.

- Chāndogya Upaniṣad.

- Ashvapati – a King in the Chāndogya Upaniṣad.

- Ashtavakra – an Upanishadic Sage mentioned in the Mahabharata, who authored Ashtavakra Gita.

Philosophers of Axial Age (600–185 BCE)

- Gotama (c. 600 BCE), logician, author of Nyaya Sutra

- Mahavira (599–527 BCE) – heavily influenced Jainism, the 24th Tirthankara of Jainism.

- Purana Kassapa

- Ajita Kesakambali

- Payasi

- Makkhali Gośāla

- Sañjaya Belaṭṭhiputta

- Mahavira

- Dandamis

- Nagasena

- Lakulisha

- Pakudha Kaccayana

- Ashtadhyayi

- Kapila (c. 500 BCE), proponent of the Samkhya system of philosophy.

- Badarayana (lived between 500 BCE and 400 BCE) – Author of Brahma Sutras.

- Jaimini (c. 400 BCE), author of Purva Mimamsa Sutras.

- Pingala (c. 500 BCE), author of the Chandas shastra

- Buddhistschool of thought

- Śāriputra

- Takshashila University

- Yoga Sutras.

- Shvetashvatara – Author of earliest textual exposition of a systematic philosophy of Shaivism.

Philosophers of Golden Age (184 BCE – 600 CE)

- Kālidāsa

- Vatsyana, known for "Kama Sutra"

- Samantabhadra, a proponent of the Jaina doctrine of Anekantavada

- Isvarakrsna

- Aryadeva, a student of Nagarjuna and contributed significantly to the Madhyamaka

- Dharmakirti

- Haribhadra

- Pujyapada

- Buddhaghosa

- Kamandaka

- Maticandra

- Prashastapada

- Bhāviveka

- Dharmapala

- Udyotakara

- Gaudapada

- Siddhasena

- Kural text, a Tamil-language treatise on morality and secular ethics

- Dignāga (c. 500), one of the founders of Buddhist school of Indian logic

- Yogacara

- Bhartrihari(c. 450–510 CE), early figure in Indic linguistic theory

- Bodhidharma (c. 440–528 CE), founder of the Zen school of Buddhism

- Siddhasena Divākara(5th century CE), Jain logician and author of important works in Sanskrit and Prakrit, such as, Nyāyāvatāra (on Logic) and Sanmatisūtra (dealing with the seven Jaina standpoints, knowledge and the objects of knowledge)

- Yogacaraschool

- Samayasāra(Essence of the Doctrine)

- Mahāyāna Buddhism

- Umāsvāti or Umasvami (2nd century CE), author of first Jain work in Sanskrit, Tattvārthasūtra, expounding the Jain philosophyin a most systematized form acceptable to all sects of Jainism

- Adi Shankara – philosopher and theologian, most renowned exponent of the Advaita Vedanta school of philosophy

Ancient Chinese philosophy

Chinese philosophy is the dominant philosophical thought in China and other countries within the

.Schools of thought

Hundred Schools of Thought

The Hundred Schools of Thought were philosophers and schools that flourished from the 6th century to 221 BCE,

- yi.[13]

- Machiavelli, and foundational for the traditional Chinese bureaucratic empire, the Legalists examined administrative methods, emphasizing a realistic consolidation of the wealth and power of autocrat and state.

- Taoism (also called Daoism), a philosophy which emphasizes the Three Jewels of the Tao: compassion, moderation, and humility, while Taoist thought generally focuses on nature, the relationship between humanity and the cosmos; health and longevity; and wu wei (action through inaction). Harmony with the Universe, or the source thereof (Tao), is the intended result of many Taoist rules and practices.

- Mohism, which advocated the idea of universal love: Mozi believed that "everyone is equal before heaven", and that people should seek to imitate heaven by engaging in the practice of collective love. His epistemology can be regarded as primitive materialist empiricism; he believed that human cognition ought to be based on one's perceptions – one's sensory experiences, such as sight and hearing – instead of imagination or internal logic, elements founded on the human capacity for abstraction. Mozi advocated frugality, condemning the Confucian emphasis on ritual and music, which he denounced as extravagant.

- Naturalism, the

- Agrarianism, or the Shen Nong, a folk hero which was portrayed in Chinese literature as "working in the fields, along with everyone else, and consulting with everyone else when any decision had to be reached."[15]

- The Gongsun Longzi.

- The School of Diplomacy or School of Vertical and Horizontal [Alliances], which focused on practical matters instead of any moral principle, so it stressed political and diplomatic tactics, and debate and lobbying skill. Scholars from this school were good orators, debaters and tacticians.

- The Miscellaneous School, which integrated teachings from different schools; for instance, Lü Buwei found scholars from different schools to write a book called Lüshi Chunqiu cooperatively. This school tried to integrate the merits of various schools and avoid their perceived flaws.

- The School of "Minor-talks", which was not a unique school of thought, but a philosophy constructed of all the thoughts which were discussed by and originated from normal people on the street.

- Another group is the School of the Military that studied strategy and the Sunzi and Sun Binwere influential leaders. However, this school was not one of the "Ten Schools" defined by Hanshu.

Early Imperial China

The founder of the

Confucianism was particularly strong during the Han dynasty, whose greatest thinker was Dong Zhongshu, who integrated Confucianism with the thoughts of the Zhongshu School and the theory of the Five Elements. He also was a promoter of the New Text school, which considered Confucius as a divine figure and a spiritual ruler of China, who foresaw and started the evolution of the world towards the Universal Peace. In contrast, there was an Old Text school that advocated the use of Confucian works written in ancient language (from this comes the denomination Old Text) that were so much more reliable. In particular, they refuted the assumption of Confucius as a godlike figure and considered him as the greatest sage, but simply a human and mortal.

The 3rd and 4th centuries saw the rise of the Xuanxue (mysterious learning), also called Neo-Taoism. The most important philosophers of this movement were Wang Bi, Xiang Xiu and Guo Xiang. The main question of this school was whether Being came before Not-Being (in Chinese, ming and wuming). A peculiar feature of these Taoist thinkers, like the Seven Sages of the Bamboo Grove, was the concept of feng liu (lit. wind and flow), a sort of romantic spirit which encouraged following the natural and instinctive impulse.

Philosophers

- Taoism

- Laozi (5th–4th century BCE)

- Zhuangzi (4th century BCE)

- Zhang Daoling

- Zhang Jue (died 184 CE)

- Ge Hong (283 – 343 CE)

- Confucianism

- Legalism

- Li Si

- Li Kui

- Han Fei

- Mi Su Yu

- Shang Yang

- Shen Buhai

- Shen Dao

- Mohism

- Mozi

- Song Xing

- Logicians

- Deng Xi

- Hui Shi (380–305 BCE)

- Gongsun Long (c. 325 – c. 250 BCE)

- Agrarianism

- Xu Xing

- Naturalism

- Zou Yan (305 – 240 BCE)

- Neotaoism

- School of Diplomacy

- Military strategy

- Sunzi(c. 500 BCE)

- Sun Bin (died 316 BCE)

See also

References

- ^ Philip G. Kreyenbroek: "Morals and Society in Zoroastrian Philosophy" in "Persian Philosophy". Companion Encyclopedia of Asian Philosophy: Brian Carr and Indira Mahalingam. Routledge, 2009.

- ^ Mary Boyce: "The Origins of Zoroastrian Philosophy" in "Persian Philosophy". Companion Encyclopedia of Asian Philosophy: Brian Carr and Indira Mahalingam. Routledge, 2009.

- ISBN 978-1845115418.

- ISBN 0-8196-0280-9.

- ^ ISBN 9231032119.

- ISBN 0-933273-35-5.

- ISBN 0-7100-9121-4.

- ^ David A. Scott. Manichaean Views of Buddhism in: History of Religions. Vol. 25, No. 2, Nov. 1985. University of Chicago Press.

- ^ Yarshater, Ehsan. 1983. The Cambridge history of Iran, volume 2. pp. 995–997

- ^ The significance of Purusha Sukta in Daily Invocations Archived 3 October 2009 at the Wayback Machine by Swami Krishnananda

- ^ P. 285 Indian sociology through Ghurye, a dictionary By S. Devadas Pillai

- ^ "Chinese philosophy", Encyclopædia Britannica, accessed 4/6/2014

- PMID 11913447, archived from the original(PDF) on 16 July 2011

- ^ "Zou Yan". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 1 March 2011.

- ^ a b Deutsch, Eliot; Ronald Bontekoei (1999). A companion to world philosophies. Wiley Blackwell. p. 183.

Further reading

- Luchte, James, Early Greek Thought: Before the Dawn, in series Bloomsbury Studies in Ancient Philosophy, Bloomsbury Publishing, London, 2011. ISBN 978-0567353313

External links

- Ancient philosophy at the Indiana Philosophy Ontology Project