Cleopatra

| Cleopatra | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

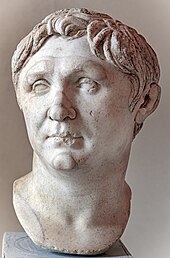

The Berlin Cleopatra, a Roman sculpture of Cleopatra wearing a royal diadem, mid-1st century BC, now in the Altes Museum, Germany[1][2][3][note 1] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Pharaoh | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Queen of the Ptolemaic Kingdom | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Reign | 51–30 BC (21 years)[4] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Coregency | See list

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Predecessor | Ptolemy XII Auletes | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Successor | Arsinoe IV (disputed, Cleopatra later usurped her from power), Ptolemy XV[note 2] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Consorts |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Born | Early 69 BC or Late 70 BC Alexandria, Egypt | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Died | 10 August 30 BC (aged 39)[note 4] Alexandria, Egpyt | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Burial | Unlocated tomb (probably in Egypt) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Dynasty | Ptolemaic dynasty | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Part of a series on |

| Cleopatra VII |

|---|

|

|

|

Cleopatra VII Thea Philopator (

In 58 BC, Cleopatra presumably accompanied her father,

In the

Cleopatra's legacy survives in ancient and modern

Etymology

The Latinized form

Background

Ptolemaic

Roman interventionism in Egypt predated the

Biography

Early childhood

Cleopatra VII was born in early 69 BC to the ruling

Reign and exile of Ptolemy XII

In 65 BC the

In 58 BC the Romans

Ptolemy XII spent nearly a year there on the outskirts of Rome, ostensibly accompanied by his daughter Cleopatra, then about 11.[57][61][note 22] Berenice IV sent an embassy to Rome to advocate for her rule and oppose the reinstatement of her father Ptolemy XII. Ptolemy had assassins kill the leaders of the embassy, an incident that was covered up by his powerful Roman supporters.[62][55][63][note 23] When the Roman Senate denied Ptolemy XII the offer of an armed escort and provisions for a return to Egypt, he decided to leave Rome in late 57 BC and reside at the Temple of Artemis in Ephesus.[64][65][66]

The Roman financiers of Ptolemy XII remained determined to restore him to power.

Gabinius was put on trial in Rome for abusing his authority, for which he was acquitted, but his second trial for accepting bribes led to his exile, from which he was recalled seven years later in 48 BC by Caesar.[75][76] Crassus replaced him as governor of Syria and extended his provincial command to Egypt, but he was killed by the Parthians at the Battle of Carrhae in 53 BC.[75][77] Ptolemy XII had Berenice IV and her wealthy supporters executed, seizing their properties.[78][79][80] He allowed Gabinius's largely Germanic and Gallic Roman garrison, the Gabiniani, to harass people in the streets of Alexandria and installed his longtime Roman financier Rabirius as his chief financial officer.[78][81][82][note 24]

Within a year Rabirius was placed under protective custody and sent back to Rome after his life was endangered for draining Egypt of its resources.[83][84][80][note 25] Despite these problems, Ptolemy XII created a will designating Cleopatra and Ptolemy XIII as his joint heirs, oversaw major construction projects such as the Temple of Edfu and a temple at Dendera, and stabilized the economy.[85][84][86][note 26] On 31 May 52 BC, Cleopatra was made a regent of Ptolemy XII, as indicated by an inscription in the Temple of Hathor at Dendera.[87][88][89][note 27] Rabirius was unable to collect the entirety of Ptolemy XII's debt by the time of the latter's death, and so it was passed on to his successors Cleopatra and Ptolemy XIII.[83][76]

Accession to the throne

Ptolemy XII died sometime before 22 March 51 BC, when Cleopatra, in her first act as queen, began her voyage to

In 50 BC

By 29 August 51 BC, official documents started listing Cleopatra as the sole ruler, evidence that she had rejected her brother Ptolemy XIII as a co-ruler.

Despite Cleopatra's rejection of him, Ptolemy XIII still retained powerful allies, notably the eunuch

Assassination of Pompey

In the summer of 49 BC, Cleopatra and

In Greece, Caesar and Pompey's forces engaged each other at the decisive

Relationship with Julius Caesar

Ptolemy XIII arrived at Alexandria at the head of his army, in clear defiance of Caesar's demand that he disband and leave his army before his arrival.[129][130] Cleopatra initially sent emissaries to Caesar, but upon allegedly hearing that Caesar was inclined to having affairs with royal women, she came to Alexandria to see him personally.[129][131][130] Historian Cassius Dio records that she did so without informing her brother, dressed in an attractive manner, and charmed Caesar with her wit.[129][132][133] Plutarch provides an entirely different account that alleges she was bound inside a bed sack to be smuggled into the palace to meet Caesar.[129][134][135][note 36]

When Ptolemy XIII realized that his sister was in the palace consorting directly with Caesar, he attempted to rouse the populace of Alexandria into a riot, but he was arrested by Caesar, who used his oratorical skills to calm the frenzied crowd.[136][137][138] Caesar then brought Cleopatra and Ptolemy XIII before the assembly of Alexandria, where Caesar revealed the written will of Ptolemy XII—previously possessed by Pompey—naming Cleopatra and Ptolemy XIII as his joint heirs.[139][137][131][note 37] Caesar then attempted to arrange for the other two siblings, Arsinoe IV and Ptolemy XIV, to rule together over Cyprus, thus removing potential rival claimants to the Egyptian throne while also appeasing the Ptolemaic subjects still bitter over the loss of Cyprus to the Romans in 58 BC.[140][137][141][note 37]

Judging that this agreement favored Cleopatra over Ptolemy XIII and that the latter's army of 20,000, including the Gabiniani, could most likely defeat Caesar's army of 4,000 unsupported troops, Potheinos decided to have Achillas lead their forces to Alexandria to attack both Caesar and Cleopatra.[140][137][142][note 38] After Caesar managed to execute Potheinos, Arsinoe IV joined forces with Achillas and was declared queen, but soon afterward had her tutor Ganymedes kill Achillas and take his position as commander of her army.[143][144][145][note 39] Ganymedes then tricked Caesar into requesting the presence of the erstwhile captive Ptolemy XIII as a negotiator, only to have him join the army of Arsinoe IV.[143][146][147] The resulting siege of the palace, with Caesar and Cleopatra trapped together inside, lasted into the following year of 47 BC.[148][127][149][note 40]

Sometime between January and March of 47 BC, Caesar's reinforcements arrived, including those led by

Caesar's term as consul had expired at the end of 48 BC.[153] However, Antony, an officer of his, helped to secure Caesar's appointment as dictator lasting for a year, until October 47 BC, providing Caesar with the legal authority to settle the dynastic dispute in Egypt.[153] Wary of repeating the mistake of Cleopatra's sister Berenice IV in having a female monarch as sole ruler, Caesar appointed Cleopatra's 12-year-old brother, Ptolemy XIV, as joint ruler with the 22-year-old Cleopatra in a nominal sibling marriage, but Cleopatra continued living privately with Caesar.[159][127][150][note 43] The exact date at which Cyprus was returned to her control is not known, although she had a governor there by 42 BC.[160][150]

Caesar is alleged to have joined Cleopatra for a cruise of the Nile and sightseeing of

Caesar departed from Egypt around April 47 BC, allegedly to confront Pharnaces II of Pontus, the son of Mithridates VI of Pontus, who was stirring up trouble for Rome in Anatolia.[167] It is possible that Caesar, married to the prominent Roman woman Calpurnia, also wanted to avoid being seen together with Cleopatra when she had their son.[167][161] He left three legions in Egypt, later increased to four, under the command of the freedman Rufio, to secure Cleopatra's tenuous position, but also perhaps to keep her activities in check.[167][168][169]

Caesarion, Cleopatra's alleged child with Caesar, was born 23 June 47 BC and was originally named "Pharaoh Caesar", as preserved on a stele at the Serapeum of Saqqara.[170][127][171][note 44] Perhaps owing to his still childless marriage with Calpurnia, Caesar remained publicly silent about Caesarion (but perhaps accepted his parentage in private).[172][note 45] Cleopatra, on the other hand, made repeated official declarations about Caesarion's parentage, naming Caesar as the father.[172][173][174]

Cleopatra and her nominal joint ruler Ptolemy XIV visited Rome sometime in late 46 BC, presumably without Caesarion, and were given lodging in Caesar's villa within the

Cleopatra's presence in Rome most likely had an effect on the events at the

Cleopatra in the Liberators' civil war

Octavian, Antony, and

While Serapion, Cleopatra's governor of Cyprus, defected to Cassius and provided him with ships, Cleopatra took her own fleet to Greece to personally assist Octavian and Antony. Her ships were heavily damaged in a Mediterranean storm and she arrived too late to aid in the fighting.[196][199] By the autumn of 42 BC, Antony had defeated the forces of Caesar's assassins at the Battle of Philippi in Greece, leading to the suicide of Cassius and Brutus.[196][200]

By the end of 42 BC, Octavian had gained control over much of

Relationship with Mark Antony

Cleopatra invited Antony to come to Egypt before departing from Tarsos, which led Antony to visit Alexandria by November 41 BC.

Cleopatra carefully chose Antony as her partner for producing further heirs, as he was deemed to be the most powerful Roman figure following Caesar's demise.[216] With his powers as a triumvir, Antony also had the broad authority to restore former Ptolemaic lands, which were currently in Roman hands, to Cleopatra.[217][218] While it is clear that both Cilicia and Cyprus were under Cleopatra's control by 19 November 38 BC, the transfer probably occurred earlier in the winter of 41–40 BC, during her time spent with Antony.[217]

By the spring of 40 BC, Antony left Egypt due to troubles in Syria, where his governor Lucius Decidius Saxa was killed and his army taken by Quintus Labienus, a former officer under Cassius who now served the Parthian Empire.[219] Cleopatra provided Antony with 200 ships for his campaign and as payment for her newly acquired territories.[219] She would not see Antony again until 37 BC, but she maintained correspondence, and evidence suggests she kept a spy in his camp.[219] By the end of 40 BC, Cleopatra had given birth to twins, a boy named Alexander Helios and a girl named Cleopatra Selene II, both of whom Antony acknowledged as his children.[220][221] Helios (the Sun) and Selene (the Moon) were symbolic of a new era of societal rejuvenation,[222] as well as an indication that Cleopatra hoped Antony would repeat the exploits of Alexander the Great by conquering the Parthians.[212]

Mark Antony's Parthian campaign in the east was disrupted by the events of the

In December 40 BC Cleopatra received

Relations between Antony and Cleopatra perhaps soured when he not only married Octavia, but also sired her two children, Antonia the Elder in 39 BC and Antonia Minor in 36 BC, and moved his headquarters to Athens.[234] However, Cleopatra's position in Egypt was secure.[212] Her rival Herod was occupied with civil war in Judea that required heavy Roman military assistance, but received none from Cleopatra.[234] Since the authority of Antony and Octavian as triumvirs had expired on 1 January 37 BC, Octavia arranged for a meeting at Tarentum, where the triumvirate was officially extended to 33 BC.[235] With two legions granted by Octavian and a thousand soldiers lent by Octavia, Antony traveled to Antioch, where he made preparations for war against the Parthians.[236]

Antony summoned Cleopatra to Antioch to discuss pressing issues, such as Herod's kingdom and financial support for his Parthian campaign.[236][237] Cleopatra brought her now three-year-old twins to Antioch, where Antony saw them for the first time and where they probably first received their surnames Helios and Selene as part of Antony and Cleopatra's ambitious plans for the future.[238][239] In order to stabilize the east, Antony not only enlarged Cleopatra's domain,[237] he also established new ruling dynasties and client rulers who would be loyal to him, yet would ultimately outlast him.[240][218][note 51]

In this arrangement Cleopatra gained significant former Ptolemaic territories in the Levant, including nearly all of

Antony's enlargement of the Ptolemaic realm by relinquishing directly controlled Roman territory was exploited by his rival Octavian, who tapped into the public sentiment in Rome against the empowerment of a foreign queen at the expense of their Republic.

In 36 BC, Cleopatra accompanied Antony to the Euphrates in his journey toward invading the Parthian Empire.[249] She then returned to Egypt, perhaps due to her advanced state of pregnancy.[250] By the summer of 36 BC, she had given birth to Ptolemy Philadelphus, her second son with Antony.[250][237]

Donations of Alexandria

As Antony prepared for another Parthian expedition in 35 BC, this time aimed at their ally

Dellius was sent as Antony's envoy to Artavasdes II in 34 BC to negotiate a potential

In an event held at the

In late 34 BC, Antony and Octavian engaged in a heated war of propaganda that would last for years.

A

Battle of Actium

In a speech to the Roman Senate on the first day of his consulship on 1 January 33 BC, Octavian accused Antony of attempting to subvert Roman freedoms and territorial integrity as a slave to his Oriental queen.[280] Before Antony and Octavian's joint imperium expired on 31 December 33 BC, Antony declared Caesarion as the true heir of Caesar in an attempt to undermine Octavian.[280] In 32 BC, the Antonian loyalists Gaius Sosius and Gnaeus Domitius Ahenobarbus became consuls. The former gave a fiery speech condemning Octavian, now a private citizen without public office, and introduced pieces of legislation against him.[279][281] During the next senatorial session, Octavian entered the Senate house with armed guards and levied his own accusations against the consuls.[279][282] Intimidated by this act, the consuls and over 200 senators still in support of Antony fled Rome the next day to join the side of Antony.[279][282][283]

Antony and Cleopatra traveled together to Ephesus in 32 BC, where she provided him with 200 of the 800 naval ships he was able to acquire.[279] Ahenobarbus, wary of having Octavian's propaganda confirmed to the public, attempted to persuade Antony to have Cleopatra excluded from the campaign against Octavian.[284][285] Publius Canidius Crassus made the counterargument that Cleopatra was funding the war effort and was a competent monarch.[284][285] Cleopatra refused Antony's requests that she return to Egypt, judging that by blocking Octavian in Greece she could more easily defend Egypt.[284][285] Cleopatra's insistence that she be involved in the battle for Greece led to the defections of prominent Romans, such as Ahenobarbus and Lucius Munatius Plancus.[284][282]

During the spring of 32 BC Antony and Cleopatra traveled to Athens, where she persuaded Antony to send Octavia an official declaration of divorce.[284][282][268] This encouraged Plancus to advise Octavian that he should seize Antony's will, invested with the Vestal Virgins.[284][282][270] Although a violation of sacred and legal rights, Octavian forcefully acquired the document from the Temple of Vesta, and it became a useful tool in the propaganda war against Antony and Cleopatra.[284][270] Octavian highlighted parts of the will, such as Caesarion being named heir to Caesar, that the Donations of Alexandria were legal, that Antony should be buried alongside Cleopatra in Egypt instead of Rome, and that Alexandria would be made the new capital of the Roman Republic.[286][282][270] In a show of loyalty to Rome, Octavian decided to begin construction of his own mausoleum at the Campus Martius.[282] Octavian's legal standing was also improved by being elected consul in 31 BC.[282] With Antony's will made public, Octavian had his casus belli, and Rome declared war on Cleopatra,[286][287][288] not Antony.[note 57] The legal argument for war was based less on Cleopatra's territorial acquisitions, with former Roman territories ruled by her children with Antony, and more on the fact that she was providing military support to a private citizen now that Antony's triumviral authority had expired.[289]

Antony and Cleopatra had a larger fleet than Octavian, but the crews of Antony and Cleopatra's navy were not all well-trained, some of them perhaps from merchant vessels, whereas Octavian had a fully professional force.

Cleopatra and Antony had the support of various allied kings, but Cleopatra had already been in conflict with Herod, and an earthquake in Judea provided him with an excuse to be absent from the campaign.

On 2 September 31 BC the naval forces of Octavian, led by Marcus Vipsanius Agrippa, met those of Antony and Cleopatra at the Battle of Actium.[295][291][287] Cleopatra, aboard her flagship, the Antonias, commanded 60 ships at the mouth of the Ambracian Gulf, at the rear of the fleet, in what was likely a move by Antony's officers to marginalize her during the battle.[295] Antony had ordered that their ships should have sails on board for a better chance to pursue or flee from the enemy, which Cleopatra, ever concerned about defending Egypt, used to swiftly move through the area of major combat in a strategic withdrawal to the Peloponnese.[296][297][298]

Burstein writes that partisan Roman writers would later accuse Cleopatra of cowardly deserting Antony, but their original intention of keeping their sails on board may have been to break the blockade and salvage as much of their fleet as possible.

Downfall and death

While Octavian occupied Athens, Antony and Cleopatra landed at

Cleopatra perhaps started to view Antony as a liability by the late summer of 31 BC, when she prepared to leave Egypt to her son Caesarion.[308] Cleopatra planned to relinquish her throne to him, take her fleet from the Mediterranean into the Red Sea, and then set sail to a foreign port, perhaps in India, where she could spend time recuperating.[308][306] However, these plans were ultimately abandoned when Malichus I, as advised by Octavian's governor of Syria, Quintus Didius, managed to burn Cleopatra's fleet in revenge for his losses in a war with Herod that Cleopatra had largely initiated.[308][306] Cleopatra had no other option but to stay in Egypt and negotiate with Octavian.[308] Although most likely later pro-Octavian propaganda, it was reported that at this time Cleopatra started testing the strengths of various poisons on prisoners and even her own servants.[309]

Cleopatra had Caesarion enter into the ranks of the

After lengthy negotiations that ultimately produced no results, Octavian set out to invade Egypt in the spring of 30 BC,[313] stopping at Ptolemais in Phoenicia, where his new ally Herod provided his army with fresh supplies.[314] Octavian moved south and swiftly took Pelousion, while Cornelius Gallus, marching eastward from Cyrene, defeated Antony's forces near Paraitonion.[315][316] Octavian advanced quickly to Alexandria, but Antony returned and won a small victory over Octavian's tired troops outside the city's hippodrome.[315][316] However, on 1 August 30 BC, Antony's naval fleet surrendered to Octavian, followed by Antony's cavalry.[315][297][317]

Cleopatra hid herself in her tomb with her close attendants and sent a message to Antony that she had committed suicide.[315][318][319] In despair, Antony responded to this by stabbing himself in the stomach and taking his own life at age 53.[315][297][306] According to Plutarch, he was still dying when brought to Cleopatra at her tomb, telling her he had died honorably and that she could trust Octavian's companion Gaius Proculeius over anyone else in his entourage.[315][320][321] It was Proculeius, however, who infiltrated her tomb using a ladder and detained the queen, denying her the ability to burn herself with her treasures.[322][323] Cleopatra was then allowed to embalm and bury Antony within her tomb before she was escorted to the palace.[322][306]

Octavian entered Alexandria, occupied the palace, and seized Cleopatra's three youngest children.

Octavian was said to have been angered by this outcome but had Cleopatra buried in royal fashion next to Antony in

Cleopatra decided in her last moments to send Caesarion away to Upper Egypt, perhaps with plans to flee to Kushite Nubia, Ethiopia, or India.[337][338][316] Caesarion, now Ptolemy XV, would reign for a mere 18 days until executed on the orders of Octavian on 29 August 30 BC, after returning to Alexandria under the false pretense that Octavian would allow him to be king.[339][340][341][note 2] Octavian was convinced by the advice of the philosopher Arius Didymus that there was room for only one Caesar in the world.[342][note 59] With the fall of the Ptolemaic Kingdom, the Roman province of Egypt was established,[343][297][344][note 60] marking the end of the Hellenistic period.[345][346][note 9] In January of 27 BC Octavian was renamed Augustus ("the revered") and amassed constitutional powers that established him as the first Roman emperor, inaugurating the Principate era of the Roman Empire.[347]

Cleopatra's kingdom and role as a monarch

Following the tradition of

Cleopatra was directly involved in the administrative affairs of her domain,

Legacy

Children and successors

After her suicide, Cleopatra's three surviving children, Cleopatra Selene II, Alexander Helios, and Ptolemy Philadelphos, were sent to Rome with Octavian's sister

The emperor Augustus installed Juba II and Cleopatra Selene II, after their wedding in 25 BC, as the new rulers of

Cleopatra Selene II died c. 5 BC, and when Juba II died in 23/24 AD he was succeeded by his son Ptolemy.[368][370] However, Ptolemy was eventually executed by the Roman emperor Caligula in 40 AD, perhaps under the pretense that Ptolemy had unlawfully minted his own royal coinage and utilized regalia reserved for the Roman emperor.[371][372] Ptolemy of Mauretania was the last known monarch of the Ptolemaic dynasty, although Queen Zenobia, of the short-lived Palmyrene Empire during the Crisis of the Third Century, would claim descent from Cleopatra.[373][374] A cult dedicated to Cleopatra still existed as late as 373 AD when Petesenufe, an Egyptian scribe of the book of Isis, explained that he "overlaid the figure of Cleopatra with gold."[375]

Roman literature and historiography

Although almost 50 ancient works of Roman historiography mention Cleopatra, these often include only terse accounts of the Battle of Actium, her suicide, and Augustan propaganda about her personal deficiencies.[377] Despite not being a biography of Cleopatra, the Life of Antonius written by Plutarch in the 1st century AD provides the most thorough surviving account of Cleopatra's life.[378][379][380] Plutarch lived a century after Cleopatra but relied on primary sources, such as Philotas of Amphissa, who had access to the Ptolemaic royal palace, Cleopatra's personal physician named Olympos, and Quintus Dellius, a close confidant of Mark Antony and Cleopatra.[381] Plutarch's work included both the Augustan view of Cleopatra—which became canonical for his period—as well as sources outside of this tradition, such as eyewitness reports.[378][380]

The Jewish Roman historian Josephus, writing in the 1st century AD, provides valuable information on the life of Cleopatra via her diplomatic relationship with Herod the Great.[382][383] However, this work relies largely on Herod's memoirs and the biased account of Nicolaus of Damascus, the tutor of Cleopatra's children in Alexandria before he moved to Judea to serve as an adviser and chronicler at Herod's court.[382][383] The Roman History published by the official and historian Cassius Dio in the early 3rd century AD, while failing to fully comprehend the complexities of the late Hellenistic world, nevertheless provides a continuous history of the era of Cleopatra's reign.[382]

Cleopatra is barely mentioned in De Bello Alexandrino, the memoirs of an unknown staff officer who served under Caesar.[386][387][388][note 62] The writings of Cicero, who knew her personally, provide an unflattering portrait of Cleopatra.[386] The Augustan-period authors Virgil, Horace, Propertius, and Ovid perpetuated the negative views of Cleopatra approved by the ruling Roman regime,[386][389] although Virgil established the idea of Cleopatra as a figure of romance and epic melodrama.[390][note 63] Horace also viewed Cleopatra's suicide as a positive choice,[391][389] an idea that found acceptance by the Late Middle Ages with Geoffrey Chaucer.[392][393]

The historians

Cleopatra's gender has perhaps led to her depiction as a minor if not insignificant figure in ancient, medieval, and even modern historiography about ancient Egypt and the Greco-Roman world.[395] For instance, the historian Ronald Syme asserted that she was of little importance to Caesar and that the propaganda of Octavian magnified her importance to an excessive degree.[395] Although the common view of Cleopatra was one of a prolific seductress, she had only two known sexual partners, Caesar and Antony, the two most prominent Romans of the time period, who were most likely to ensure the survival of her dynasty.[396][397] Plutarch described Cleopatra as having had a stronger personality and charming wit than physical beauty.[398][15][399][note 66]

Cultural depictions

Depictions in ancient art

Statues

Cleopatra was depicted in various ancient works of art, in the Egyptian as well as Hellenistic-Greek and Roman styles.[2] Surviving works include statues, busts, reliefs, and minted coins,[2][376] as well as ancient carved cameos,[402] such as one depicting Cleopatra and Antony in Hellenistic style, now in the Altes Museum, Berlin.[1] Contemporary images of Cleopatra were produced both in and outside of Ptolemaic Egypt. For instance, there was once a large gilded bronze statue of Cleopatra inside the Temple of Venus Genetrix in Rome, the first time that a living person had their statue placed next to that of a deity in a Roman temple.[3][185][403] It was erected there by Caesar and remained in the temple at least until the 3rd century AD, its preservation perhaps owing to Caesar's patronage, although Augustus did not remove or destroy artworks in Alexandria depicting Cleopatra.[404][405]

Since the 1950s scholars have debated whether or not the

Coinage portraits

Surviving coinage of Cleopatra's reign include specimens from every regnal year, from 51 to 30 BC.[412] Cleopatra, the only Ptolemaic queen to issue coins on her own behalf, almost certainly inspired her partner Caesar to become the first living Roman to present his portrait on his own coins.[410][note 67] Cleopatra was the first foreign queen to have her image appear on Roman currency.[413] Coins dated to the period of her marriage to Antony, which also bear his image, portray the queen as having a very similar aquiline nose and prominent chin as that of her husband.[3][414] These similar facial features followed an artistic convention that represented the mutually-observed harmony of a royal couple.[3][2]

Her strong, almost masculine facial features in these particular coins are strikingly different from the smoother, softer, and perhaps idealized

The inscriptions on the coins are written in Greek, but also in the

Various coins, such as a silver

Greco-Roman busts and heads

Of the surviving Greco-Roman-style busts and heads of Cleopatra,[note 69] the sculpture known as the "Berlin Cleopatra", located in the Antikensammlung Berlin collection at the Altes Museum, possesses her full nose, whereas the head known as the "Vatican Cleopatra", located in the Vatican Museums, is damaged with a missing nose.[423][424][425][note 70] Both the Berlin Cleopatra and Vatican Cleopatra have royal diadems, similar facial features, and perhaps once resembled the face of her bronze statue housed in the Temple of Venus Genetrix.[424][426][425][note 71]

Both heads are dated to the mid-1st century BC and were found in Roman villas along the

A third sculpted portrait of Cleopatra accepted by scholars as being authentic survives at the Archaeological Museum of Cherchell, Algeria.[405][360][361] This portrait features the royal diadem and similar facial features as the Berlin and Vatican heads, but has a more unique hairstyle and may actually depict Cleopatra Selene II, daughter of Cleopatra.[361][428][233][note 50] A possible Parian-marble sculpture of Cleopatra wearing a vulture headdress in Egyptian style is located at the Capitoline Museums.[429] Discovered near a sanctuary of Isis in Rome and dated to the 1st century BC, it is either Roman or Hellenistic-Egyptian in origin.[430]

Other possible sculpted depictions of Cleopatra include one in the British Museum, London, made of limestone, which perhaps only depicts a woman in her entourage during her trip to Rome.[1][420] The woman in this portrait has facial features similar to others (including the pronounced aquiline nose), but lacks a royal diadem and sports a different hairstyle.[1][420] However, the British Museum head, once belonging to a full statue, could potentially represent Cleopatra at a different stage in her life and may also betray an effort by Cleopatra to discard the use of royal insignia (i.e. the diadem) to make herself more appealing to the citizens of Republican Rome.[420] Duane W. Roller speculates that the British Museum head, along with those in the Egyptian Museum, Cairo, the Capitoline Museums, and in the private collection of Maurice Nahmen, while having similar facial features and hairstyles as the Berlin portrait but lacking a royal diadem, most likely represent members of the royal court or even Roman women imitating Cleopatra's popular hairstyle.[431]

-

Cleopatra, mid-1st century BC, with a "melon" hairstyle and

-

Profile view of the Vatican Cleopatra

-

Cleopatra, mid-1st century BC, showing Cleopatra with a "melon" hairstyle and

-

Profile view of the Berlin Cleopatra

Paintings

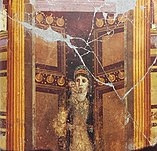

In the House of Marcus Fabius Rufus at Pompeii, Italy, a mid-1st century BC Second Style wall painting of the goddess Venus holding a cupid near massive temple doors is most likely a depiction of Cleopatra as Venus Genetrix with her son Caesarion.[407][432] The commission of the painting most likely coincides with the erection of the Temple of Venus Genetrix in the Forum of Caesar in September 46 BC, where Caesar had a gilded statue erected depicting Cleopatra.[407][432] This statue likely formed the basis of her depictions in both sculpted art as well as this painting at Pompeii.[407][433]

The woman in the painting wears a royal diadem over her head and is strikingly similar in appearance to the Vatican Cleopatra, which bears possible marks on the marble of its left cheek where a cupid's arm may have been torn off.[407][434][425][note 74] The room with the painting was walled off by its owner, perhaps in reaction to the execution of Caesarion in 30 BC by order of Octavian, when public depictions of Cleopatra's son would have been unfavorable with the new Roman regime.[407][435]

Behind her golden diadem, crowned with a red jewel, is a translucent veil with crinkles that suggest the "melon" hairstyle favored by the queen.[434][note 75] Her ivory-white skin, round face, long aquiline nose, and large round eyes were features common in both Roman and Ptolemaic depictions of deities.[434] Roller affirms that "there seems little doubt that this is a depiction of Cleopatra and Caesarion before the doors of the Temple of Venus in the Forum Julium and, as such, it becomes the only extant contemporary painting of the queen."[407]

Sophonisba was also a more obscure figure when the painting was made, while Cleopatra's suicide was far more famous.[301] An asp is absent from the painting, but many Romans held the view that she received poison in another manner than a venomous snakebite.[439] A set of double doors on the rear wall of the painting, positioned very high above the people in it, suggests the described layout of Cleopatra's tomb in Alexandria.[301] A male servant holds the mouth of an artificial Egyptian crocodile (possibly an elaborate tray handle), while another man standing by is dressed as a Roman.[301]

In 1818 a now lost

A Roman panel painting from Herculaneum, Italy, dated to the 1st century AD possibly depicts Cleopatra.[47][48] In it she wears a royal diadem, red or reddish-brown hair pulled back into a bun,[note 78] pearl-studded hairpins,[442] and earrings with ball-shaped pendants, the white skin of her face and neck set against a stark black background.[47] Her hair and facial features are similar to those in the sculpted Berlin and Vatican portraits as well as her coinage.[47] A highly similar painted bust of a woman with a blue headband in the House of the Orchard at Pompeii features Egyptian-style imagery, such as a Greek-style sphinx, and may have been created by the same artist.[47]

Portland Vase

The Portland Vase, a Roman cameo glass vase dated to the Augustan period and now in the British Museum, includes a possible depiction of Cleopatra with Antony.[443][445] In this interpretation, Cleopatra can be seen grasping Antony and drawing him toward her while a serpent (i.e. the asp) rises between her legs, Eros floats above, and Anton, the alleged ancestor of the Antonian family, looks on in despair as his descendant Antony is led to his doom.[443][444] The other side of the vase perhaps contains a scene of Octavia, abandoned by her husband Antony but watched over by her brother, the emperor Augustus.[443][444] The vase would thus have been created no earlier than 35 BC, when Antony sent his wife Octavia back to Italy and stayed with Cleopatra in Alexandria.[443]

Native Egyptian art

The Bust of Cleopatra in the Royal Ontario Museum represents a bust of Cleopatra in the Egyptian style.[446] Dated to the mid-1st century BC, it is perhaps the earliest depiction of Cleopatra as both a goddess and ruling pharaoh of Egypt.[446] The sculpture also has pronounced eyes that share similarities with Roman copies of Ptolemaic sculpted works of art.[447] The Dendera Temple complex, near Dendera, Egypt, contains Egyptian-style carved relief images along the exterior walls of the Temple of Hathor depicting Cleopatra and her young son Caesarion as a grown adult and ruling pharaoh making offerings to the gods.[448][449] Augustus had his name inscribed there following the death of Cleopatra.[448][450]

A large Ptolemaic black

-

A granite Egyptian bust of Cleopatra from the Royal Ontario Museum, mid-1st century BC

-

A marble statue of Cleopatra with her cartouche inscribed on the upper right arm and wearing a diadem with a triple uraeus, from the Metropolitan Museum of Art[453]

-

Possible sculpted head of Cleopatra VII wearing an Egyptian-style vulture headdress, discovered in Rome, either

Medieval and Early Modern reception

In modern times Cleopatra has become an icon of popular culture,[376] a reputation shaped by theatrical representations dating back to the Renaissance as well as paintings and films.[455] This material largely surpasses the scope and size of existent historiographic literature about her from classical antiquity and has made a greater impact on the general public's view of Cleopatra than the latter.[456] The 14th-century English poet Geoffrey Chaucer, in The Legend of Good Women, contextualized Cleopatra for the Christian world of the Middle Ages.[457] His depiction of Cleopatra and Antony, her shining knight engaged in courtly love, has been interpreted in modern times as being either playful or misogynistic satire.[457]

Chaucer highlighted Cleopatra's relationships with only two men as hardly the life of a seductress and wrote his works partly in reaction to the negative depiction of Cleopatra in

Cleopatra appeared in

In the performing arts, the death of

Modern depictions and brand imaging

In

Shakespeare's Antony and Cleopatra was considered canonical by the Victorian era.

Written works

Whereas myths about Cleopatra persist in popular media, important aspects of her career go largely unnoticed, such as her command of naval forces and administrative acts. Publications on ancient Greek medicine attributed to her are, likely to be the work of a physician by the same name writing in the late first century AD.[483] Ingrid D. Rowland, who highlights that the "Berenice called Cleopatra" cited by the 3rd- or 4th-century female Roman physician Metrodora was likely conflated by medieval scholars as referring to Cleopatra.[484] Only fragments exist of these medical and cosmetic writings, such as those preserved by Galen, including remedies for hair disease, baldness, and dandruff, along with a list of weights and measures for pharmacological purposes.[485][18][486] Aëtius of Amida attributed a recipe for perfumed soap to Cleopatra, while Paul of Aegina preserved alleged instructions of hers for dyeing and curling hair.[485]

Ancestry

Cleopatra belonged to the

Cleopatra I Syra was the only member of the Ptolemaic dynasty known for certain to have introduced some non-Greek ancestry.[497][498] Her mother Laodice III was a daughter born to King Mithridates II of Pontus, a Persian of the Mithridatic dynasty, and his wife Laodice who had a mixed Greek-Persian heritage.[499] Cleopatra I Syra's father Antiochus III the Great was a descendant of Queen Apama, the Sogdian Iranian wife of Seleucus I Nicator.[497][498][500][note 84] It is generally believed that the Ptolemies did not intermarry with native Egyptians.[39][501][note 85] Michael Grant asserts that there is only one known Egyptian mistress of a Ptolemy and no known Egyptian wife of a Ptolemy, further arguing that Cleopatra probably did not have any Egyptian ancestry and "would have described herself as Greek."[497][note 86]

Stacy Schiff writes that Cleopatra was a Macedonian Greek with some Persian ancestry, arguing that it was rare for the Ptolemies to have an Egyptian mistress.[502][note 87] Duane W. Roller speculates that Cleopatra could have been the daughter of a theoretical half-Macedonian-Greek, half-Egyptian woman from Memphis in northern Egypt belonging to a family of priests dedicated to Ptah (a hypothesis not generally accepted in scholarship),[note 88] but contends that whatever Cleopatra's ancestry, she valued her Greek Ptolemaic heritage the most.[503][note 89] Ernle Bradford writes that Cleopatra challenged Rome not as an Egyptian woman "but as a civilized Greek."[504]

Claims that Cleopatra was an

The family tree given below also lists Cleopatra V as a daughter of

| Ptolemy V Epiphanes | Cleopatra I Syra | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ptolemy VI Philometor | Cleopatra II | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ptolemy VIII Physcon | Cleopatra III | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

Ptolemy IX Lathyros | Cleopatra IV | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ptolemy X Alexander I | Berenice III | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

Cleopatra V Tryphaena | Ptolemy XII Auletes | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Cleopatra VII | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

See also

Notes

- Via Appia. For further validation about the Berlin Cleopatra, see Pina Polo (2013, pp. 184–186), Roller (2010, pp. 54, 174–175), Jones (2006, p. 33), and Hölbl (2001, p. 234).

- ^ a b Roller (2010, p. 149) and Skeat (1953, pp. 99–100) explain the nominal short-lived reign of Caesarion as lasting 18 days in 30 August BC. However, Duane W. Roller, relaying Theodore Cressy Skeat, affirms that Caesarion's reign "was essentially a fiction created by Egyptian chronographers to close the gap between [Cleopatra's] death and official Roman control of Egypt (under the new pharaoh, Octavian)", citing, for instance, the Stromata by Clement of Alexandria (Roller 2010, pp. 149, 214, footnote 103).Plutarch, translated by Jones (2006, p. 187), wrote in vague terms that "Octavian had Caesarion killed later, after Cleopatra's death."

- ^ a b c Grant (1972, pp. 3–4, 17), Fletcher (2008, pp. 69, 74, 76), Jones (2006, p. xiii), Preston (2009, p. 22), Schiff (2011, p. 28) and Burstein (2004, p. 11) label the wife of Ptolemy XII Auletes as Cleopatra V Tryphaena, while Dodson & Hilton (2004, pp. 268–269, 273) and Roller (2010, p. 18) call her Cleopatra VI Tryphaena, due to the confusion in primary sources conflating these two figures, who may have been one and the same. As explained by Whitehorne (1994, p. 182), Cleopatra VI may have actually been a daughter of Ptolemy XII who appeared in 58 BC to rule jointly with her alleged sister Berenice IV (while Ptolemy XII was exiled and living in Rome), whereas Ptolemy XII's wife Cleopatra V perhaps died as early as the winter of 69–68 BC, when she disappears from historical records. Roller (2010, pp. 18–19) assumes that Ptolemy XII's wife, who he numbers as Cleopatra VI, was merely absent from the court for a decade after being expelled for an unknown reason, eventually ruling jointly with her daughter Berenice IV. Fletcher (2008, p. 76) explains that the Alexandrians deposed Ptolemy XII and installed "his eldest daughter, Berenike IV, and as co-ruler recalled Cleopatra V Tryphaena from 10 years' exile from the court. Although later historians assumed she must have been another of Auletes' daughters and numbered her 'Cleopatra VI', it seems she was simply the fifth one returning to replace her brother and former husband Auletes."

- ^ a b 12 August 30 BC in the later Julian calendar Skeat (1953, pp. 98–100).

- ^ The name Cleopatra is pronounced /ˌkliːəˈpætrə/ KLEE-ə-PAT-rə, or sometimes /ˌkliːəˈpɑːtrə/ -PAH-trə in British English, see HarperCollins, the same as in American English. Cordry (1998, p. 44). Her name was pronounced [kleoˈpatra tʰeˈa pʰiloˈpato̞r] in the Greek dialect of Egypt (see Koine Greek phonology)

- ^ Also "Thea Neotera", lit. "the younger goddess"; and "Philopatris", lit. "loving her country"; see Fischer-Bovet (2015)

- ^ She was also a diplomat, naval commander, linguist, and medical author; see Roller (2010, p. 1) and Bradford (2000, p. 13).

- ^ Southern (2009, p. 43) writes about Ptolemy I Soter: "The Ptolemaic dynasty, of which Cleopatra was the last representative, was founded at the end of the fourth century BC. The Ptolemies were not of Egyptian extraction, but stemmed from Ptolemy Soter, a Macedonian Greek in the entourage of Alexander the Great."For additional sources that describe the Ptolemaic dynasty as "Macedonian Greek", please see Roller (2010, pp. 15–16), Jones (2006, pp. xiii, 3, 279), Kleiner (2005, pp. 9, 19, 106, 183), Jeffreys (1999, p. 488) and Johnson (1999, p. 69). Alternatively, Grant (1972, p. 3) describes them as a "Macedonian, Greek-speaking" dynasty. Other sources such as Burstein (2004, p. 64) and Pfrommer & Towne-Markus (2001, p. 9) describe the Ptolemies as "Greco-Macedonian", or rather Macedonians who possessed a Greek culture, as in Pfrommer & Towne-Markus (2001, pp. 9–11, 20).

- ^ Hellenistic Greeks were viewed by contemporary Romans as having declined and diminished in greatness since the age of Classical Greece, an attitude that has continued even into the works of modern historiography. Regarding Hellenistic Egypt, Grant argues, "Cleopatra VII, looking back upon all that her ancestors had done during that time, was not likely to make the same mistake. But she and her contemporaries of the first century BC had another, peculiar, problem of their own. Could the 'Hellenistic Age' (which we ourselves often regard as coming to an end in about her time) still be said to exist at all, could any Greek age, now that the Romanswere the dominant power? This was a question never far from Cleopatra's mind. But it is quite certain that she considered the Greek epoch to be by no means finished, and intended to do everything in her power to ensure its perpetuation."

- ^ Late Egyptian, is why Ancient Greek (i.e. Koine Greek) was used along with Late Egyptian on official court documents such as the Rosetta Stone ("Radio 4 Programmes – A History of the World in 100 Objects, Empire Builders (300 BC – 1 AD), Rosetta Stone". BBC. Archived from the original on 23 May 2010. Retrieved 7 June 2010.).As explained by Burstein (2004, pp. 43–54), Ptolemaic Alexandria was considered a polis (city-state) separate from the country of Egypt, with citizenship reserved for Greeks and Ancient Macedonians, but various other ethnic groups resided there, especially the Jews, as well as native Egyptians, Syrians, and Nubians.For further validation, see Grant (1972, p. 3).For the multiple languages spoken by Cleopatra, see Roller (2010, pp. 46–48) and Burstein (2004, pp. 11–12).For further validation about Ancient Greek being the official language of the Ptolemaic dynasty, see Jones (2006, p. 3).

- ^ Tyldesley (2017) offers an alternative rendering of the title Cleopatra VII Thea Philopator as "Cleopatra the Father-Loving Goddess".

- Ptolemaic period, along with a survey of the various ethnic groups residing there, see Burstein (2004, pp. 43–61).For further validation about the founding of Alexandria by Alexander the Great, see Jones (2006, p. 6).For further validation of Ptolemaic rulers being crowned at Memphis, see Jeffreys (1999, p. 488).

- ^ For further information, see Grant (1972, pp. 20, 256, footnote 42).

- Ptolemaic Egypt gradually abandoned the Ancient Macedonian language. For further information and validation see Schiff (2011, p. 36).

- ^ Grant (1972, p. 3) states that Cleopatra could have been born in either late 70 BC or early 69 BC.

- ^ For further information and validation see Schiff (2011, p. 28), Kleiner (2005, p. 22), Bennett (1997, pp. 60–63), Bianchi (2005), and Meadows (2001, p. 23). For alternate speculation, see Burstein (2004, p. 11) and Roller (2010, pp. 15, 18, 166). For a comparison of arguments about Cleopatra's maternity, see Prose (2022, p. 38).

- Ptolemy XII or his wife, identical to that of Cleopatra V, Jones (2006, p. 28) states that Ptolemy XII had six children, while Roller (2010, p. 16) mentions only five.

- Berenice II, the style had fallen from fashion for almost two centuries until revived by Cleopatra; yet as both traditionalist and innovator, she wore her version without her predecessor's fine head veil. And whereas they had both been blonde like Alexander, Cleopatra may well have been a redhead, judging from the portrait of a flame-haired woman wearing the royal diadem surrounded by Egyptian motifswhich has been identified as Cleopatra."

- ^ For further information and validation, see Grant (1972, pp. 12–13). In 1972, Michael Grant calculated that 6,000 talents, the price of Ptolemy XII's fee for receiving the title "friend and ally of the Roman people" from the triumvirs Pompey and Julius Caesar, would be worth roughly £7 million or US$17 million, roughly the entire annual tax revenue for Ptolemaic Egypt.

- ^ For political background information on the Roman annexation of Cyprus, a move pushed for in the Roman Senate by Publius Clodius Pulcher, see Grant (1972, pp. 13–14).

- ^ For further information, see Grant (1972, pp. 15–16).

- ^ Fletcher (2008, pp. 76–77) expresses little doubt about this: "deposed in late summer 58 BC and fearing for his life, Auletes had fled both his palace and his kingdom, although he was not completely alone. For one Greek source reveals he had been accompanied 'by one of his daughters', and since his eldest Berenice IV, was monarch, and the youngest, Arsinoe, little more than a toddler, it is generally assumed that this must have been his middle daughter and favourite child, eleven-year-old Cleopatra."

- ^ For further information, see Grant (1972, p. 16).

- ^ For further information on Roman financier Rabirius, as well as the Gabiniani left in Egypt by Gabinius, see Grant (1972, pp. 18–19).

- ^ For further information, see Grant (1972, p. 18).

- ^ For further information, see Grant (1972, pp. 19–20, 27–29).

- ^ For further information, see Grant (1972, pp. 28–30).

- ^ It is disputed whether Cleopatra was deliberately depicted as a male or whether a stele made under her father with his portrait was later inscribed with an inscription for Cleopatra. On this and other uncertainties regarding this stele, see Pfeiffer (2015, pp. 177–181).

- ^ For further information, see Fletcher (2008, pp. 88–92) and Jones (2006, pp. 31, 34–35).Fletcher (2008, pp. 85–86) states that the partial solar eclipse of 7 March 51 BC marked the death of Ptolemy XII and accession of Cleopatra to the throne, although she apparently suppressed the news of his death, alerting the Roman Senate to this fact months later in a message they received on 30 June 51 BC.However, Grant (1972, p. 30) claims that the Senate was informed of his death on 1 August 51 BC. Michael Grant indicates that Ptolemy XII could have been alive as late as May, while an ancient Egyptian source affirms he was still ruling with Cleopatra by 15 July 51 BC, although by this point Cleopatra most likely "hushed up her father's death" so that she could consolidate her control of Egypt.

- Macedon ... killed Arsinoë's small children in front of her. Now queen without a kingdom, Arsinoë fled to Egypt, where she was welcomed by her full brother Ptolemy II. Not content, however, to spend the rest of her life as a guest at the Ptolemaic court, she had Ptolemy II's wife exiled to Upper Egypt and married him herself around 275 B.C. Though such an incestuous marriage was considered scandalous by the Greeks, it was allowed by Egyptian custom. For that reason, the marriage split public opinion into two factions. The loyal side celebrated the couple as a return of the divine marriage of Zeus and Hera, whereas the other side did not refrain from profuse and obscene criticism. One of the most sarcastic commentators, a poet with a very sharp pen, had to flee Alexandria. The unfortunate poet was caught off the shore of Crete by the Ptolemaic navy, put in an iron basket, and drowned. This and similar actions seemingly slowed down vicious criticism."

- ^ For further information, see Fletcher (2008, pp. 92–93).

- ^ For further information, see Fletcher (2008, pp. 96–97) and Jones (2006, p. 39).

- ^ For further information, see Jones (2006, pp. 39–41).

- ^ a b For further information, see Fletcher (2008, p. 98) and Jones (2006, pp. 39–43, 53–55).

- ^ For further information, see Fletcher (2008, pp. 98–100) and Jones (2006, pp. 53–55).

- ^ For further information, see Burstein (2004, p. 18) and Fletcher (2008, pp. 101–103).

- ^ a b For further information, see Fletcher (2008, p. 113).

- ^ For further information, see Fletcher (2008, p. 118).

- ^ For further information, see Burstein (2004, p. 76).

- ^ For further information, see Burstein (2004, pp. xxi, 19) and Fletcher (2008, pp. 118–120).

- ^ For further information, see Fletcher (2008, pp. 119–120).As part of the siege of Alexandria, Burstein (2004, p. 19) states that Caesar's reinforcements came in January, but Roller (2010, p. 63) says that his reinforcements came in March.

- ^ For further information and validation, see Anderson (2003, p. 39) and Fletcher (2008, p. 120).

- ^ For further information and validation, see Fletcher (2008, p. 121) and Jones (2006, p. xiv).Roller (2010, pp. 64–65) states that at this point (47 BC) Ptolemy XIV was 12 years old, while Burstein (2004, p. 19) claims that he was still only 10 years of age.

- ^ For further information and validation, see Anderson (2003, p. 39) and Fletcher (2008, pp. 154, 161–162).

- ^ Roller (2010, p. 70) writes the following about Caesar and his parentage of Caesarion: "The matter of parentage became so tangled in the propaganda war between Antonius and Octavian in the late 30s B.C.—it was essential for one side to prove and the other to reject Caesar's role—that it is impossible today to determine Caesar's actual response. The extant information is almost contradictory: it was said that Caesar denied parentage in his will but acknowledged it privately and allowed the use of the name Caesarion. Caesar's associate C. Oppius even wrote a pamphlet proving that Caesarion was not Caesar's child, and C. Helvius Cinna—the poet who was killed by rioters after Antonius' funeral oration—was prepared in 44 B.C. to introduce legislation to allow Caesar to marry as many wives as he wished for the purpose of having children. Although much of this talk was generated after Caesar's death, it seems that he wished to be as quiet as possible about the child but had to contend with Cleopatra's repeated assertions."

- ^ For further information and validation, see Jones (2006, pp. xiv, 78).

- ^ For further information, see Fletcher (2008, pp. 214–215).

- ^ As explained by Burstein (2004, p. 23), Cleopatra, having read Antony's personality, boldly presented herself to him as the Egyptian goddess Isis (in the appearance of the Greek goddess Aphrodite) meeting her divine husband Osiris (in the form of the Greek god Dionysus), knowing that the priests of the Temple of Artemis at Ephesus had associated Antony with Dionysus shortly before this encounter. According to Brown (2011), a cult surrounding Isis had been spreading across the region for hundreds of years, and Cleopatra, like many of her predecessors, sought to identify herself with Isis and be venerated. In addition, some surviving coins of Cleopatra also depict her as Venus–Aphrodite, as explained by Fletcher (2008, p. 205).

- ^ For further information about Publius Ventidius Bassus and his victory over Parthian forces at the Battle of Mount Gindarus, see Kennedy (1996, pp. 80–81).

- ^ a b c Ferroukhi (2001a, p. 219) provides a detailed discussion about this bust and its ambiguities, noting that it could represent Cleopatra, but that it is more likely her daughter Cleopatra Selene II. Kleiner (2005, pp. 155–156) argues in favor of its depicting Cleopatra rather than her daughter, while Varner (2004, p. 20) mentions only Cleopatra as a possible likeness. Roller (2003, p. 139) observes that it could be either Cleopatra or Cleopatra Selene II, while arguing the same ambiguity applies to the other sculpted head from Cherchel featuring a veil. In regards to the latter head, Ferroukhi (2001b, p. 242) indicates it as a possible portrait of Cleopatra, not Cleoptra Selene II, from the early 1st century AD while also arguing that its masculine features, earrings, and apparent toga (the veil being a component of it) could likely mean it was intended to depict a Numidian nobleman. Fletcher (2008, image plates between pp. 246–247) disagrees about the veiled head, arguing that it was commissioned by Cleopatra Selene II at Iol (Caesarea Mauretaniae) and was meant to depict her mother, Cleopatra.

- ^ According to Roller (2010, pp. 91–92), these client state rulers installed by Antony included Herod, Amyntas of Galatia, Polemon I of Pontus, and Archelaus of Cappadocia.

- Octavia Minor provided Antony with 1,200 troops, not 2,000 as stated in Roller (2010, pp. 97–98) and Burstein (2004, pp. 27–28).

- ^ Roller (2010, p. 100) says that it is unclear if Antony and Cleopatra were ever truly married. Burstein (2004, pp. xxii, 29) says that the marriage publicly sealed Antony's alliance with Cleopatra and in defiance of Octavian he would divorce Octavia in 32 BC. Coins of Antony and Cleopatra depict them in the typical manner of a Hellenistic royal couple, as explained by Roller (2010, p. 100).

- ^ Jones (2006, p. xiv) writes that "Octavian waged a propaganda war against Antony and Cleopatra, stressing Cleopatra's status as a woman and a foreigner who wished to share in Roman power."

- ^ Stanley M. Burstein, in Burstein (2004, p. 33) provides the name Quintus Cascellius as the recipient of the tax exemption, not the Publius Canidius Crassus provided by Duane W. Roller in Roller (2010, p. 134).

- ^ Reece (2017, p. 203) notes that "[t]he fragmentary texts of ancient Greek papyri do not often make their way into the modern public arena, but this one has, and with fascinating results, while remaining almost entirely unacknowledged is the remarkable fact that Cleopatra's one-word subscription contains a blatant spelling error: γινέσθωι, with a superfluous iota adscript." This spelling error "has not been noted by the popular media", however, being "simply transliterated [...] including, without comment, the superfluous iota adscript" (p. 208). Even in academic sources, the misspelling was largely unacknowledged or quietly corrected (pp. 206–208, 210).Although described as "'normal' orthography" (in contrast with "'correct' orthography") by Peter van Minnen (p. 208), the spelling error is "much rarer and more puzzling" than the sort one would expect from the Greek papyri from Egypt (p. 210)—so rare, in fact, that it occurs only twice in the 70,000 Greek papyri between the 3rd century BC and 8th century AD in the Papyrological Navigator's database. This is especially so when considering it was added to a word "with no etymological or morphological reason for having an iota adscript" (p. 210) and was written by "the well-educated, native Greek-speaking, queen of Egypt" Cleopatra VII (p. 208).

- ^ As explained by Jones (2006, p. 147), "politically, Octavian had to walk a fine line as he prepared to engage in open hostilities with Antony. He was careful to minimize associations with civil war, as the Roman people had already suffered through many years of civil conflict and Octavian could risk losing support if he declared war on a fellow citizen."

- ^ For the translated accounts of both Plutarch and Dio, Jones (2006, pp. 194–195) writes that the implement used to puncture Cleopatra's skin was a hairpin.

- ^ Jones (2006, p. 187), translating Plutarch, quotes Arius Didymus as saying to Octavian that "it is not good to have too many Caesars", which was apparently enough to convince Octavian to have Caesarion killed.

- governors of Egypt, the first of whom was Gallus. For further information, see Southern (2014, p. 185) and Roller (2010, p. 151).

- ^ Walker (2001, p. 312) writes the following about the raised relief on the gilded silver dish: "Conspicuously mounted on the cornucopia is a gilded crescent moon set on a pine cone. Around it are piled pomegranates and bunches of grapes. Engraved on the horn are images of Helios (the sun), in the form of a youth dressed in a short cloak, with the hairstyle of Alexander the Great, the head surrounded by rays ... The symbols on the cornucopia can indeed be read as references to the Ptolemaic royal house and specifically to Cleopatra Selene, represented in the crescent moon, and to her twin brother, Alexander Helios, whose eventual fate after the conquest of Egypt is unknown. The viper seems to be linked with the pantheress and the intervening symbols of fecundity rather than the suicide of Cleopatra VII. The elephant scalp could refer to Cleopatra Selene's status as ruler, with Juba II, of Mauretania. The visual correspondence with the veiled head from Cherchel encourages this identification, and many of the symbols used on the dish also appear on the coinage of Juba II."

- ^ Jones (2006, p. 60) offers speculation that the author of De Bello Alexandrino, written in Latin prose sometime between 46 and 43 BC, was a certain Aulus Hirtius, a military officer serving under Caesar.

- ^ Burstein (2004, p. 30) writes that Virgil, in his Aeneid, described the Battle of Actium against Cleopatra "as a clash of civilizations in which Octavian and the Roman gods preserved Italy from conquest by Cleopatra and the barbaric animal-headed gods of Egypt."

- ^ For further information and extracts of Strabo's account of Cleopatra in his Geographica see Jones (2006, pp. 28–30).

- Demotic Egyptianlanguage. Overall this is a much smaller body of surviving native texts than those of any other period of Ptolemaic Egypt.

- ^ For the description of Cleopatra by Plutarch, who claimed that her beauty was not "completely incomparable" but that she had a "captivating" and "stimulating" personality, see Jones (2006, pp. 32–33).

- ^ Fletcher (2008, p. 205) writes the following: "Cleopatra was the only female Ptolemy to issue coins on her own behalf, some showing her as Venus-Aphrodite. Caesar now followed her example and, taking the same bold step, became the first living Roman to appear on coins, his rather haggard profile accompanied by the title 'Parens Patriae', 'Father of the Fatherland'."

- ^ For further information, see Raia & Sebesta (2017).

- ^ There is academic disagreement on whether the following portraits are considered "heads" or "busts". For instance, Raia & Sebesta (2017) exclusively uses the former, while Grout (2017b) prefers the latter.

- ^ For further information and validation, see Curtius (1933, pp. 182–192), Walker (2008, p. 348), Raia & Sebesta (2017) and Grout (2017b).

- ^ For further information and validation, see Grout (2017b) and Roller (2010, pp. 174–175).

- ^ For further information, see Curtius (1933, pp. 182–192), Walker (2008, p. 348) and Raia & Sebesta (2017).

- ^ Blaise Pascal remarked in his Pensées (1670): "Cleopatra's nose: had it been shorter, the whole aspect of the world would have been altered." (Pascal 1910, sec. II, no. 162) According to (Perry & Williams 2019), a less aquiline nose would have diminished her chances of becoming ruler of Egypt and attract men of the First and Second Triumvirate, which would have changed the Battle of Actium, and subsequent European history.

- ^ The observation that the left cheek of the Vatican Cleopatra once had a cupid's hand that was broken off was first suggested by Ludwig Curtius in 1933. Kleiner concurs with this assessment. See Kleiner (2005, p. 153), as well as Walker (2008, p. 40) and Curtius (1933, pp. 182–192). While Kleiner (2005, p. 153) has suggested the lump on top of this marble head perhaps contained a broken-off uraeus, Curtius (1933, p. 187) offered the explanation that it once held a sculpted representation of a jewel.

- ^ Curtius (1933, p. 187) wrote that the damaged lump along the hairline and diadem of the Vatican Cleopatra likely contained a sculpted representation of a jewel, which Walker (2008, p. 40) directly compares to the painted red jewel in the diadem worn by Venus, most likely Cleopatra, in the fresco from Pompeii.

- ^ For further information about the painting in the House of Giuseppe II (Joseph II) at Pompeii and the possible identification of Cleopatra as one of the figures, see Pucci (2011, pp. 206–207, footnote 27).

- ^ In Pratt & Fizel (1949, pp. 14–15), Frances Pratt and Becca Fizel rejected the idea proposed by some scholars in the 19th and early 20th centuries that the painting was perhaps done by an artist of the Italian Renaissance. Pratt and Fizel highlighted the Classical style of the painting as preserved in textual descriptions and the steel engraving. They argued that it was unlikely for a Renaissance period painter to have created works with encaustic materials, conducted thorough research into Hellenistic period Egyptian clothing and jewelry as depicted in the painting, and then precariously placed it in the ruins of the Egyptian temple at Hadrian's Villa.

- ^ Walker & Higgs (2001, pp. 314–315) describe her hair as reddish brown, while Fletcher (2008, p. 87) describes her as a flame-haired redhead and, in Fletcher (2008, image plates and captions between pp. 246–247), likewise describes her as a red-haired woman.

- ^ Preston (2009, p. 305) comes to a similar conclusion about native Egyptian depictions of Cleopatra: "Apart from certain temple carvings, which are anyway in a highly stylised pharaonic style and give little clue to Cleopatra's real appearance, the only certain representations of Cleopatra are those on coins. The marble head in the Vatican is one of three sculptures generally, though not universally, accepted by scholars to be depictions of Cleopatra."

- ^ For further information on Cleopatra's Macedonian Greek lineage, see Pucci (2011, p. 201), Grant (1972, pp. 3–5), Burstein (2004, pp. 3, 34, 36, 43, 63–64) and Royster (2003, pp. 47–49).

- ^ For further information and validation of the foundation of Hellenistic Egypt by Alexander the Great and Cleopatra's ancestry stretching back to Ptolemy I Soter, see Grant (1972, pp. 7–8) and Jones (2006, p. 3).

- ^ For further information, see Grant (1972, pp. 3–4) and Burstein (2004, p. 11).

- Cleopatra V Tryphaenaas a possible cousin or sister of Ptolemy XII Auletes.

- ^ For the Sogdian ancestry of Apama, wife of Seleucus I Nicator, see Holt (1989, pp. 64–65, footnote 63).

- ^ As explained by Burstein (2004, pp. 47–50), the main ethnic groups of Ptolemaic Egypt were Egyptians, Greeks, and Jews, each of whom were legally segregated, living in different residential quarters and forbidden to intermarry with one another in the multicultural cities of Alexandria, Naucratis, and Ptolemais Hermiou. It had been speculated in some circles that Pasherienptah III, the High Priest of Ptah at Memphis, Egypt, was Cleopatra's half-cousin, speculation which has been recently refuted by Cheshire (2011, pp. 20–30).

- ^ Grant (1972, p. 5) argues that Cleopatra's grandmother, i.e. the mother of Ptolemy XII, might have been a Syrian (though conceding that "it is possible she was also partly Greek"), but almost certainly not an Egyptian because there is only one known Egyptian mistress of a Ptolemaic ruler throughout their entire dynasty.

- ^ Schiff (2011, p. 42) further argues that, considering Cleopatra's ancestry, she was not dark-skinned, though notes Cleopatra was likely not among the Ptolemies with fair features, and instead would have been honey-skinned, citing as evidence that her relatives were described as such and it "would have presumably applied to her as well." Goldsworthy (2010, pp. 127, 128) agrees to this, contending that Cleopatra, having Macedonian blood with a little Syrian, was probably not dark-skinned (as Roman propaganda never mentions it), writing "fairer skin is marginally more likely considering her ancestry," though also notes she could have had a "darker more Mediterranean complexion" because of her mixed ancestry. Grant (1972, p. 5) agrees to Goldsworthy's latter speculation of her skin color, that though almost certainly not Egyptian, Cleopatra had a darker complexion due to being Greek mixed with Persian and possible Syrian ancestry. Preston (2009, p. 77) agrees with Grant that, considering this ancestry, Cleopatra was "almost certainly dark-haired and olive-skinned." Bradford (2000, p. 14) contends that it is "reasonable to infer" Cleopatra had dark hair and "pale olive skin."

- Ptolemy VIII. However, this speculation was refuted by Egyptologist Wendy Cheshire, which was later validated by papyrologist Sandra Lippert. See Cheshire (2011, pp. 20–30) and Lippert (2013, pp. 33–48).

- ^ Schiff (2011, pp. 2) concurs with this, concluding that Cleopatra "upheld the family tradition." As noted by Dudley (1960, pp. 57), Cleopatra and her family were "the successor[s] to the native Pharaohs, exploiting through a highly organized bureaucracy the great natural resources of the Nile Valley."

- ^ Grant (1972, p. 4) argues that if Cleopatra had been illegitimate, her "numerous Roman enemies would have revealed this to the world."

- ^ The family tree and short discussions of the individuals can be found in Dodson & Hilton (2004, pp. 268–281). Aidan Dodson and Dyan Hilton refer to Cleopatra V as Cleopatra VI and Cleopatra Selene of Syria is called Cleopatra V Selene. Dotted lines in the chart below indicate possible but disputed parentage.

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h Raia & Sebesta (2017).

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Sabino & Gross-Diaz (2016).

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Grout (2017b).

- ^ Burstein (2004), pp. xx–xxiii, 155.

- ^ Royster (2003), p. 48.

- ^ a b Muellner.

- ^ a b c Roller (2010), pp. 15–16.

- ^ Roller (2010), pp. 15–16, 39.

- ^ Fletcher (2008), pp. 55–57.

- ^ Burstein (2004), p. 15.

- ^ Fletcher (2008), pp. 84, 215.

- ^ a b Roller (2010), p. 18.

- ^ Roller (2010), pp. 32–33.

- ^ Fletcher (2008), pp. 1, 3, 11, 129.

- ^ a b Burstein (2004), p. 11.

- ^ Roller (2010), pp. 29–33.

- ^ Fletcher (2008), pp. 1, 5, 13–14, 88, 105–106.

- ^ a b c d Burstein (2004), pp. 11–12.

- ^ Schiff (2011), p. 35.

- ^ a b Roller (2010), pp. 46–48.

- ^ Fletcher (2008), pp. 5, 82, 88, 105–106.

- ^ Roller (2010), pp. 46–48, 100.

- ^ Roller (2010), pp. 38–42.

- ^ Burstein (2004), pp. xviii, 10.

- ^ Grant (1972), pp. 9–12.

- ^ a b c d e Roller (2010), p. 17.

- ^ a b Grant (1972), pp. 10–11.

- ^ a b Burstein (2004), p. xix.

- ^ Grant (1972), p. 11.

- ^ Burstein (2004), p. 12.

- ^ Fletcher (2008), p. 74.

- ^ Grant (1972), p. 3.

- ^ Roller (2010), p. 15.

- ^ a b c d Grant (1972), p. 4.

- ^ Preston (2009), p. 22.

- ^ Jones (2006), pp. xiii, 28.

- ^ a b Roller (2010), p. 16.

- ^ a b Anderson (2003), p. 38.

- ^ a b c Fletcher (2008), p. 73.

- ^ a b Roller (2010), pp. 18–19.

- ^ Fletcher (2008), pp. 68–69.

- ^ Roller (2010), p. 19.

- ^ Fletcher (2008), p. 69.

- ^ Roller (2010), pp. 45–46.

- ^ Roller (2010), p. 45.

- ^ Fletcher (2008), p. 81.

- ^ a b c d e f Walker & Higgs (2001), pp. 314–315.

- ^ a b Fletcher (2008), p. 87, image plates and captions between pp. 246–247.

- ^ Roller (2010), p. 20.

- ^ Burstein (2004), pp. xix, 12–13.

- ^ Roller (2010), pp. 20–21.

- ^ Burstein (2004), pp. xx, 12–13.

- ^ Fletcher (2008), pp. 74–76.

- ^ Roller (2010), p. 21.

- ^ a b Burstein (2004), p. 13.

- ^ a b c Fletcher (2008), p. 76.

- ^ a b c d Roller (2010), p. 22.

- ^ a b Burstein (2004), pp. xx, 13, 75.

- ^ Burstein (2004), pp. 13, 75.

- ^ Grant (1972), pp. 14–15.

- ^ a b Fletcher (2008), pp. 76–77.

- ^ Roller (2010), p. 23.

- ^ Fletcher (2008), pp. 77–78.

- ^ Roller (2010), pp. 23–24.

- ^ Fletcher (2008), p. 78.

- ^ Grant (1972), p. 16.

- ^ a b c Roller (2010), p. 24.

- ^ Burstein (2004), pp. xx, 13.

- ^ Grant (1972), pp. 16–17.

- ^ Burstein (2004), pp. 13, 76.

- ^ Carey (n.d.).

- ^ a b Roller (2010), pp. 24–25.

- ^ Burstein (2004), p. 76.

- ^ Burstein (2004), pp. 23, 73.

- ^ a b Roller (2010), p. 25.

- ^ a b Grant (1972), p. 18.

- ^ a b Burstein (2004), p. xx.

- ^ a b Roller (2010), pp. 25–26.

- ^ Burstein (2004), pp. 13–14, 76.

- ^ a b Fletcher (2008), pp. 11–12.

- ^ Burstein (2004), pp. 13–14.

- ^ Fletcher (2008), pp. 11–12, 80.

- ^ a b Roller (2010), p. 26.

- ^ a b Burstein (2004), p. 14.

- ^ Roller (2010), pp. 26–27.

- ^ Fletcher (2008), pp. 80, 85.

- ^ Roller (2010), p. 27.

- ^ Burstein (2004), pp. xx, 14.

- ^ Fletcher (2008), pp. 84–85.

- ^ a b c Hölbl (2001), p. 231.

- ^ Roller (2010), pp. 53, 56.

- ^ Burstein (2004), pp. xx, 15–16.

- ^ Roller (2010), pp. 53–54.

- ^ a b Burstein (2004), pp. 16–17.

- ^ a b Roller (2010), p. 53.

- ^ a b Roller (2010), pp. 54–56.

- ^ a b c Burstein (2004), p. 16.

- ^ a b Roller (2010), p. 56.

- ^ Fletcher (2008), pp. 91–92.

- ^ a b c Roller (2010), pp. 36–37.

- ^ a b c Burstein (2004), p. 5.

- ^ a b c Grant (1972), pp. 26–27.

- ^ a b Roller (2010), pp. 56–57.

- ^ Fletcher (2008), pp. 73, 92–93.

- ^ Fletcher (2008), pp. 92–93.

- ^ a b Roller (2010), p. 57.

- ^ a b c Burstein (2004), pp. xx, 17.

- ^ a b Roller (2010), p. 58.

- ^ Fletcher (2008), pp. 94–95.

- ^ Fletcher (2008), p. 95.

- ^ Roller (2010), pp. 58–59.

- ^ Burstein (2004), p. 17.

- ^ Fletcher (2008), pp. 95–96.

- ^ Roller (2010), p. 59.

- ^ a b c Fletcher (2008), p. 96.

- ^ a b Roller (2010), pp. 59–60.

- ^ a b Fletcher (2008), pp. 97–98.

- ^ a b Bringmann (2007), p. 259.

- ^ a b Burstein (2004), pp. xxi, 17.

- ^ a b c Roller (2010), p. 60.

- ^ Fletcher (2008), p. 98.

- ^ Jones (2006), pp. 39–43, 53.

- ^ Burstein (2004), pp. xxi, 17–18.

- ^ a b Roller (2010), pp. 60–61.

- ^ Bringmann (2007), pp. 259–260.

- ^ a b Burstein (2004), pp. xxi, 18.

- ^ a b c d e f g Bringmann (2007), p. 260.

- ^ Ashton (2001b), p. 164.

- ^ a b c d Roller (2010), p. 61.

- ^ a b Fletcher (2008), p. 100.

- ^ a b Burstein (2004), p. 18.

- ^ Hölbl (2001), pp. 234–235.

- ^ Jones (2006), pp. 56–57.

- ^ Hölbl (2001), p. 234.

- ^ Jones (2006), pp. 57–58.

- ^ Roller (2010), pp. 61–62.

- ^ a b c d Hölbl (2001), p. 235.

- ^ Fletcher (2008), pp. 112–113.

- ^ Roller (2010), pp. 26, 62.

- ^ a b Roller (2010), p. 62.

- ^ Burstein (2004), pp. 18, 76.

- ^ Burstein (2004), pp. 18–19.

- ^ a b c Roller (2010), p. 63.

- ^ Hölbl (2001), p. 236.

- ^ Fletcher (2008), pp. 118–119.

- ^ Burstein (2004), pp. xxi, 76.

- ^ Fletcher (2008), p. 119.

- ^ Roller (2010), pp. 62–63.

- ^ Hölbl (2001), pp. 235–236.

- ^ a b c Burstein (2004), p. 19.

- ^ Roller (2010), pp. 63–64.

- ^ Burstein (2004), pp. xxi, 19, 76.

- ^ a b c Roller (2010), p. 64.

- ^ Burstein (2004), pp. xxi, 19–21, 76.

- ^ Fletcher (2008), p. 172.

- ^ Roller (2010), pp. 64, 69.

- ^ Burstein (2004), pp. xxi, 19–20.

- ^ Fletcher (2008), p. 120.

- ^ Roller (2010), pp. 64–65.

- ^ Roller (2010), p. 65.

- ^ a b Burstein (2004), pp. 19–20.

- ^ Fletcher (2008), p. 125.

- ^ a b Roller (2010), pp. 65–66.

- ^ Fletcher (2008), p. 126.

- ^ Roller (2010), p. 66.

- ^ Fletcher (2008), pp. 108, 149–150.

- ^ a b c Roller (2010), p. 67.

- ^ Burstein (2004), p. 20.

- ^ Fletcher (2008), p. 153.

- ^ Roller (2010), pp. 69–70.

- ^ a b Burstein (2004), pp. xxi, 20.

- ^ a b Roller (2010), p. 70.

- ^ Fletcher (2008), pp. 162–163.

- ^ a b c Jones (2006), p. xiv.

- ^ Roller (2010), p. 71.

- ^ Fletcher (2008), pp. 179–182.

- ^ Roller (2010), pp. 21, 57, 72.

- ^ Burstein (2004), pp. xxi, 20, 64.

- ^ Fletcher (2008), pp. 181–182.

- ^ a b Roller (2010), p. 72.

- ^ Fletcher (2008), pp. 194–195.

- ^ Roller (2010), pp. 72, 126.

- ^ a b Burstein (2004), p. 21.

- ^ Fletcher (2008), pp. 201–202.

- ^ a b Roller (2010), pp. 72, 175.

- ^ Fletcher (2008), pp. 195–196, 201.

- ^ a b c Roller (2010), pp. 72–74.

- ^ a b c Fletcher (2008), pp. 205–206.

- ^ a b Roller (2010), p. 74.

- ^ a b Burstein (2004), pp. xxi, 21.

- ^ Fletcher (2008), pp. 207–213.

- ^ Fletcher (2008), pp. 213–214.

- ^ Roller (2010), pp. 74–75.

- ^ Burstein (2004), pp. xxi, 22.

- ^ Roller (2010), pp. 77–79, Figure 6.

- ^ a b c d e f Roller (2010), p. 75.

- ^ Burstein (2004), pp. xxi, 21–22.

- ^ a b Burstein (2004), p. 22.

- ^ Burstein (2004), pp. 22–23.

- ^ Burstein (2004), pp. xxi, 22–23.

- ^ Roller (2010), p. 76.

- ^ Roller (2010), pp. 76–77.

- ^ a b Burstein (2004), pp. xxi, 23.

- ^ Roller (2010), p. 77.

- ^ Roller (2010), pp. 77–79.

- ^ a b Burstein (2004), p. 23.

- ^ a b c Roller (2010), p. 79.

- ^ Burstein (2004), pp. xxi, 24, 76.

- ^ a b Burstein (2004), p. 24.

- ^ Burstein (2004), pp. xxii, 24.

- ^ Roller (2010), pp. 79–80.

- ^ a b c d e Burstein (2004), p. 25.

- ^ Roller (2010), pp. 77–79, 82.

- ^ Bivar (1983), p. 58.

- ^ Brosius (2006), p. 96.

- ^ Roller (2010), pp. 81–82.

- ^ a b Roller (2010), pp. 82–83.

- ^ a b c d e f Bringmann (2007), p. 301.

- ^ a b c Roller (2010), p. 83.

- ^ Roller (2010), pp. 83–84.

- ^ Burstein (2004), pp. xxii, 25.

- ^ a b Roller (2010), p. 84.

- ^ Burstein (2004), p. 73.

- ^ Roller (2010), pp. 84–85.

- ^ a b Roller (2010), p. 85.

- ^ Roller (2010), pp. 85–86.

- ^ Burstein (2004), pp. xxii, 25, 73.

- ^ a b c Roller (2010), p. 86.

- ^ a b Roller (2010), pp. 86–87.

- ^ a b c Burstein (2004), p. 26.

- ^ Fletcher (2008), image plates between pp. 246–247.

- ^ Ferroukhi (2001b), p. 242.

- ^ a b c Roller (2003), p. 139.

- ^ a b Roller (2010), p. 89.

- ^ Roller (2010), pp. 89–90.

- ^ a b Roller (2010), p. 90.

- ^ a b c d e f Burstein (2004), pp. xxii, 25–26.

- ^ Roller (2010), pp. 90–91.

- ^ a b c d Burstein (2004), p. 77.

- ^ Roller (2010), pp. 91–92.

- ^ a b Roller (2010), p. 92.

- ^ Roller (2010), pp. 92–93.