Clergy

This article needs additional citations for verification. (February 2021) |

Clergy are formal leaders within established religions. Their roles and functions vary in different religious traditions, but usually involve presiding over specific rituals and teaching their religion's doctrines and practices. Some of the terms used for individual clergy are clergyman, clergywoman, clergyperson, churchman, cleric, ecclesiastic, and vicegerent while clerk in holy orders has a long history but is rarely used.[citation needed]

In Christianity, the specific names and roles of the clergy vary by denomination and there is a wide range of formal and informal clergy positions, including deacons, elders, priests, bishops, preachers, pastors, presbyters, ministers, and the pope.

In

In the Jewish tradition, a religious leader is often a rabbi (teacher) or hazzan (cantor).

Etymology

The word cleric comes from the

The use of the word cleric is also appropriate for

A priesthood is a body of

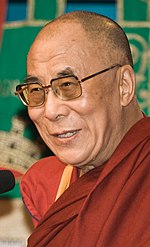

Buddhism

In general, the

While female monastic (

The diversity of Buddhist traditions makes it difficult to generalize about Buddhist clergy. In the United States,

Currently in North America, there are both celibate and non-celibate clergy in a variety of Buddhist traditions from around the world. In some cases they are forest dwelling monks of the Theravada tradition and in other cases they are married clergy of a Japanese Zen lineage and may work a secular job in addition to their role in the Buddhist community. There is also a growing realization that traditional training in ritual and meditation as well as philosophy may not be sufficient to meet the needs and expectations of American lay people. Some communities have begun exploring the need for training in counseling skills as well. Along these lines, at least two fully accredited Master of Divinity programs are currently available: one at Naropa University in Boulder, CO and one at the University of the West in Rosemead, CA.

Titles for Buddhist clergy include:

In Theravada:

- Acharya

- Ajahn

- Anagarika

- Ayya

- Bhante

- Dasa sil mata

- Luang Por

- Maechi or Mae chee

- Phra

- Sayadaw

- Sikkhamānā

- Thilashin

In Mahayana:

In Vajrayana:

Christianity

In general, Christian clergy are

Types of clerics are distinguished from offices, even when the latter are commonly or exclusively occupied by clerics. A Roman Catholic cardinal, for instance, is almost without exception a cleric, but a cardinal is not a type of cleric. An archbishop is not a distinct type of cleric, but is simply a bishop who occupies a particular position with special authority. Conversely, a youth minister at a parish may or may not be a cleric. Different churches have different systems of clergy, though churches with similar polity have similar systems.

Anglicanism

In

For a short period of history before the ordination of women as deacons, priests and bishops began within Anglicanism, women could be deaconesses. Although they were usually considered having a ministry distinct from deacons they often had similar ministerial responsibilities.

In Anglicanism all clergy are permitted to marry. In most national churches women may become deacons or priests, but while fifteen out of 38 national churches allow for the consecration of women as bishops, only five have ordained any. Celebration of the Eucharist is reserved for priests and bishops.

National Anglican churches are presided over by one or more primates or metropolitans (archbishops or presiding bishops). The senior archbishop of the Anglican Communion is the Archbishop of Canterbury, who acts as leader of the Church of England and 'first among equals' of the primates of all Anglican churches.

Being a deacon, priest or bishop is considered a function of the person and not a job. When priests retire they are still priests even if they no longer have any active ministry. However, they only hold the basic rank after retirement. Thus a retired archbishop can only be considered a bishop (though it is possible to refer to "Bishop John Smith, the former Archbishop of York"), a canon or archdeacon is a priest on retirement and does not hold any additional honorifics.

For the forms of address for Anglican clergy, see Forms of address in the United Kingdom.

-

Sir George Fleming, 2nd Baronet, British churchman.

-

Charles Wesley Leffingwell, Episcopal priest

Baptist

The

Catholic Church

Holy Orders is one of the Seven Sacraments, enumerated at the Council of Trent, that the Magisterium considers to be of divine institution. In the Catholic Church, only men are permitted to be clerics.[citation needed]

In the

Members of institutes of consecrated life and societies of apostolic life are clerics only if they have received Holy Orders. Thus, unordained monks, friars, nuns, and religious brothers and sisters are not part of the clergy.

The Code of Canon Law and the Code of Canons of the Eastern Churches prescribe that every cleric must be enrolled or "incardinated" in a diocese or its equivalent (an apostolic vicariate, territorial abbey, personal prelature, etc.) or in a religious institute, society of apostolic life or secular institute.[14][13] The need for this requirement arose because of the trouble caused from the earliest years of the Church by unattached or vagrant clergy subject to no ecclesiastical authority and often causing scandal wherever they went.[15]

Current canon law prescribes that to be ordained a priest, an education is required of two years of philosophy and four of theology, including study of dogmatic and moral theology, the Holy Scriptures, and canon law have to be studied within a seminary or an ecclesiastical faculty at a university.[16][17]

Eastern Orthodoxy

| Part of a series on the |

| Eastern Orthodox Church |

|---|

| Overview |

The

Within each of these three ranks there are found a number of titles. Bishops may have the title of

The lower clergy are not ordained through cheirotonia (laying on of hands) but through a blessing known as cheirothesia (setting-aside). These clerical ranks are

Ordination of a bishop, priest, deacon or subdeacon must be conferred during the

Bishops are usually drawn from the ranks of the archimandrites, and are required to be celibate; however, a non-monastic priest may be ordained to the episcopate if he no longer lives with his wife (following Canon XII of the Quinisext Council of Trullo)[19] In contemporary usage such a non-monastic priest is usually tonsured to the monastic state, and then elevated to archimandrite, at some point prior to his consecration to the episcopacy. Although not a formal or canonical prerequisite, at present bishops are often required to have earned a university degree, typically but not necessarily in theology.

Usual titles are Your Holiness for a patriarch (with Your All-Holiness reserved for the Ecumenical Patriarch of Constantinople), Your Beatitude for an archbishop/metropolitan overseeing an autocephalous Church, Your Eminence for an archbishop/metropolitan generally, Master or Your Grace for a bishop and Father for priests, deacons and monks,[20] although there are variations between the various Orthodox Churches. For instance, in Churches associated with the Greek tradition, while the Ecumenical Patriarch is addressed as "Your All-Holiness", all other Patriarchs (and archbishops/metropolitans who oversee autocephalous Churches) are addressed as "Your Beatitude".[21]

Orthodox priests, deacons, and subdeacons must be either married or celibate (preferably monastic) prior to ordination, but may not marry after ordination. Remarriage of clergy following divorce or widowhood is forbidden. Married clergy are considered as best-suited to staff parishes, as a priest with a family is thought better qualified to counsel his flock.[22] It has been common practice in the Russian tradition for unmarried, non-monastic clergy to occupy academic posts.

Methodism

In the Methodist Churches, candidates for ordination are "licensed" to the ministry for a period of time (typically one to three years) prior to being ordained. This period typically is spent performing the duties of ministry under the guidance, supervision, and evaluation of a more senior, ordained minister. In some denominations, however, licensure is a permanent, rather than a transitional state for ministers assigned to certain specialized ministries, such as music ministry or youth ministry.

Latter-day Saints

Generally, all worthy males age 12 and above receive the

Lutheranism

There is only one order of clergy in the Lutheran church, namely the office of pastor. This is stated in the Augsburg Confession, article 14.[26] Howeverer, for practical and historical reasons, many Lutheran churches have different roles of pastors. Some pastors are functioning as deacons, others as parish priests and yet some as bishops and even archbishops. Lutherans have no principal aversion against having a pope as the leading bishop. But the Roman Catholic view of the papacy is considered antichristian.[27]

The

Reformed

The

In

Hinduism

A Hindu priest may refer to either of the following:

- A Pujari (IAST: Pūjārī) or an Archaka is a Hindu temple priest.[29]

- A Purohita (IAST: Purōhita) officiates and performs rituals and ceremonies, and is usually linked to a specific family or, historically, a dynasty.[30]

Traditionally, priests have predominantly come from the Brahmin varna, whose male members are designated for the function in the Hindu texts.[31][32]

Islam

The title mullah (a Persian variation of the Arabic maula, "master"), commonly translated "cleric" in the West and thought to be analogous to "priest" or "rabbi", is a title of address for any educated or respected figure, not even necessarily (though frequently) religious. The title sheikh ("elder") is used similarly.

Most of the religious titles associated with Islam are scholastic or academic in nature: they recognize the holder's exemplary knowledge of the theory and practice of ad-dín (religion), and do not confer any particular spiritual or sacerdotal authority. The most general such title is `alim (pl. `ulamah), or "scholar". This word describes someone engaged in advanced study of the traditional Islamic sciences (`ulum) at an Islamic university or madrasah jami`ah. A scholar's opinions may be valuable to others because of his/her knowledge in religious matters; but such opinions should not generally be considered binding, infallible, or absolute, as the individual Muslim is directly responsible to God for his or her own religious beliefs and practice.

There is no sacerdotal office corresponding to the Christian priest or Jewish kohen, as there is no sacrificial rite of atonement comparable to the Eucharist or the Korban. Ritual slaughter or dhabihah, including the qurban at `Idu l-Ad'ha, may be performed by any adult Muslim who is physically able and properly trained. Professional butchers may be employed, but they are not necessary; in the case of the qurban, it is especially preferable to slaughter one's own animal if possible.[36]

Sunni

The nearest analogue among Sunni Muslims to the parish priest or pastor, or to the "pulpit rabbi" of a synagogue, is called the imam khatib. This compound title is merely a common combination of two elementary offices: leader (imam) of the congregational prayer, which in most mosques is performed at the times of all daily prayers; and preacher (khatib) of the sermon or khutba of the obligatory congregational prayer at midday every Friday. Although either duty can be performed by anyone who is regarded as qualified by the congregation, at most well-established mosques imam khatib is a permanent part-time or full-time position. He may be elected by the local community, or appointed by an outside authority – e.g., the national government, or the waqf that sustains the mosque. There is no ordination as such; the only requirement for appointment as an imam khatib is recognition as someone of sufficient learning and virtue to perform both duties on a regular basis, and to instruct the congregation in the basics of Islam.

The title

There are several specialist offices pertaining to the study and administration of Islamic law or .

Shia

In modern

Sufism

The spiritual guidance function known in many Christian denominations as "pastoral care" is fulfilled for many Muslims by a murshid ("guide"), a master of the spiritual sciences and disciplines known as tasawuf or Sufism. Sufi guides are commonly styled Shaikh in both speaking and writing; in North Africa they are sometimes called marabouts. They are traditionally appointed by their predecessors, in an unbroken teaching lineage reaching back to Muhammad. (The lineal succession of guides bears a superficial similarity to Christian ordination and apostolic succession, or to Buddhist dharma transmission; but a Sufi guide is regarded primarily as a specialized teacher and Islam denies the existence of an earthly hierarchy among believers.)

Muslims who wish to learn Sufism dedicate themselves to a murshid's guidance by taking an oath called a bai'ah. The aspirant is then known as a murid ("disciple" or "follower"). A murid who takes on special disciplines under the guide's instruction, ranging from an intensive spiritual retreat to voluntary poverty and homelessness, is sometimes known as a dervish.

During the Islamic Golden Age, it was common for scholars to attain recognized mastery of both the "exterior sciences" (`ulum az-zahir) of the madrasahs as well as the "interior sciences" (`ulum al-batin) of Sufism. Al-Ghazali and Rumi are two notable examples.

Ahmadiyya

The highest office an Ahmadi can hold is that of

Judaism

Since the time of the destruction of the Temple of Jerusalem, the religious leaders of Judaism have often been

Since the early medieval era an additional communal role, the Hazzan (cantor) has existed as well. Cantors have sometimes been the only functionaries of a synagogue, empowered to undertake religio-civil functions like witnessing marriages. Cantors do provide leadership of actual services, primarily because of their training and expertise in the music and prayer rituals pertaining to them, rather than because of any spiritual or "sacramental" distinction between them and the laity. Cantors as much as rabbis have been recognized by civil authorities in the United States as clergy for legal purposes, mostly for awarding education degrees and their ability to perform weddings, and certify births and deaths.

Additionally, Jewish authorities license mohalim, people specially trained by experts in Jewish law and usually also by medical professionals to perform the ritual of circumcision.[42] Traditional Orthodox Judaism does not generally license women as mohelot, unless a Jewish male expert is absent, but other movements of Judaism do. They are appropriately called mohelot (pl. of mohelet, f. of mohel).[42] As the j., the Jewish News Weekly of Northern California, states, "...there is no halachic prescription against female mohels, [but] none exist in the Orthodox world, where the preference is that the task be undertaken by a Jewish man.".[42] In many places, mohalim are also licensed by civil authorities, as circumcision is technically a surgical procedure. Kohanim, who must avoid contact with dead human body parts (such as the removed foreskin) for ritual purity, cannot act as mohalim,[citation needed] but some mohalim are also either rabbis or cantors.

Another licensed cleric in Judaism is the

Then there is the mashgiach/mashgicha. Mashgichim are observant Jews who supervise the kashrut status of a kosher establishment. The mashgichim must know the Torah laws of kashrut, and how they apply in the environment they are supervising. This can vary. In many instances, the mashgiach/mashgicha is a rabbi. This helps, since rabbinical students learn the laws of kosher as part of their syllabus. However, not all mashgichim are rabbis, and not all rabbis are qualified to be mashgichim.

Orthodox Judaism

In contemporary Orthodox Judaism, women are usually forbidden from becoming rabbis or cantors.[citation needed] Most Orthodox rabbinical seminaries or yeshivas also require dedication of many years to education, but few require a formal degree from a civil education institution that often define Christian clergy. Training is often focused on Jewish law, and some Orthodox Yeshivas forbid secular education.

In Hasidic Judaism, generally understood as a branch of Orthodox Judaism, there are dynastic spiritual leaders known as Rebbes, often translated in English as "Grand Rabbi". The office of Rebbe is generally a hereditary one, but may also be passed from Rebbe to student or by recognition of a congregation conferring a sort of coronation to their new Rebbe. Although one does not need to be an ordained Rabbi to be a Rebbe, most Rebbes today are ordained Rabbis. Since one does not need to be an ordained rabbi to be a Rebbe, at some points in history there were female Rebbes as well, particularly the Maiden of Ludmir.

Conservative Judaism

In Conservative Judaism, both men and women are ordained as rabbis and cantors. Conservative Judaism differs with Orthodoxy in that it sees Jewish Law as binding but also as subject to many interpretations, including more liberal interpretations. Academic requirements for becoming a rabbi are rigorous. First earn a bachelor's degree before entering rabbinical school. Studies are mandated in pastoral care and psychology, the historical development of Judaism and most importantly the academic study of Bible, Talmud and rabbinic literature, philosophy and theology, liturgy, Jewish history, and Hebrew literature of all periods.

Reconstructionist and Reform Judaism

Reconstructionist Judaism and Reform Judaism do not maintain the traditional requirements for study as rooted in Jewish Law and traditionalist text. Both men and women may be rabbis or cantors. The rabbinical seminaries of these movements hold that one must first earn a bachelor's degree before entering the rabbinate. In addition studies are mandated in pastoral care and psychology, the historical development of Judaism; and academic biblical criticism. Emphasis is placed not on Jewish law, but rather on sociology, modern Jewish philosophy, theology and pastoral care.

Sikhism

Zoroastrianism

Mobad and Magi are Clergy of Zoroastrianism. Kartir was one of the powerful and influential of them.

Traditional religions

Historically

have performed ritual ceremonies for centuries for the sustenance of the entire planet and its people.Health risks for ministry in the United States

In recent years, studies have suggested that American clergy in certain Protestant, Evangelical and Jewish traditions are more at risk than the general population of obesity, hypertension and depression.[citation needed] Their life expectancies have fallen in recent years and in the last decade[when?] their use of antidepressants has risen.[citation needed] Several religious bodies in the United States (Methodist, Episcopal, Baptist and Lutheran) have implemented measures to address the issue, through wellness campaigns, for example – but also by simply ensuring that clergy take more time off.

This article needs additional citations for verification. (November 2022) |

It is unclear whether similar symptoms affect American Muslim clerics, although an anecdotal comment by one American imam suggested that leaders of mosques may also share these problems.[44]

One exception to the findings of these studies is the case of American Catholic priests, who are required by canon law to take a spiritual retreat each year, and four weeks of vacation.[citation needed] Sociological studies at the University of Chicago have confirmed this exception; the studies also took the results of several earlier studies into consideration and included Roman Catholic priests nationwide.[45] It remains unclear whether American clergy in other religious traditions experience the same symptoms, or whether clergy outside the United States are similarly affected.[citation needed]

See also

References

- ^ Harper, Douglas. "cleric". Online Etymology Dictionary. Archived from the original on 2016-10-29 – via etymonline.com.

- ^ Harper, Douglas. "clergy". Online Etymology Dictionary. Archived from the original on 2016-10-29 – via etymonline.com.

- ^ Harper, Douglas. "clerk". Online Etymology Dictionary. Archived from the original on 2016-10-29 – via etymonline.com.

- ^ "Cleric". Catholic Encyclopedia. Archived from the original on 2018-08-20 – via newadvent.org.

- ^ Paul VI, Apostolic letter motu proprio Ministeria quaedam nos. 2–4, 64 AAS 529 (1972).

- ^ Ministeria quaedam no. 1; CIC Canon 266 § 1.

- ^ Nedungatt, George (2002). "Clerics". A Guide to the Eastern Code. CCEO Canon 327. pp. 255, 260.

- ^ Korean Buddhism#Buddhism during Japanese colonial rule

- ^ "Names of Women Ancestors" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-11-17. Retrieved 2013-10-23.

- ^ 1Tim 3

- ^ "Code of Canon Law, Canon 207". Archived from the original on 12 March 2020. Retrieved 25 November 2011.

- ^ "Ministeria quaedam - Disciplina circa Primam Tonsuram, Ordines Minores et Subdiaconatus in Ecclesia Latina innovatur, Litterae Apostolicae Motu Proprio datae, Die 15 m. Augusti a. 1972, Paulus PP.VI - Paulus PP. VI". The Holy See. Archived from the original on 2011-11-03. Retrieved 2020-03-15.

- ^ a b "Codex Canonum Ecclesiarum orientalium, die XVIII Octobris anno MCMXC - Ioannes Paulus PP. II - Ioannes Paulus II". The Holy See. Archived from the original on 2011-06-04. Retrieved 2020-03-15.

- ^ "Code of Canon Law - IntraText". The Holy See. Archived from the original on 2021-01-25. Retrieved 2020-03-15.

- ISBN 9780809140664), p. 329

- ^ "Code of Canon Law - IntraText". The Holy See. Archived from the original on 2011-05-08. Retrieved 2020-03-15.

- ^ "Code of Canons of the Eastern Churches, canons 342-356". Archived from the original on 2011-06-04. Retrieved 2020-03-15.

- ISBN 9783700303121.

- ^ Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers CCEL.org Archived 2005-07-20 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Clergy Etiquette Archived 2009-11-22 at the Wayback Machine", Orthodox Christian Information Center.

- ^ "Forms of Addresses and Salutations for Orthodox Clergy". Greek Orthodox Archdiocese of America. Archived from the original on Feb 6, 2017.

- ^ Ken Parry, David Melling, Dimitri Brady, Sidney Griffith & John Healey (eds.), 1999, The Blackwell Dictionary of Eastern Christianity, Oxford, pp116-7

- ^ "Questions and Answers - ensign". ChurchofJesusChrist.org. Archived from the original on 2020-02-19. Retrieved 2019-07-15.

- ^ "General Authorities," Archived 2014-11-11 at the Wayback Machine Encyclopedia of Mormonism, p. 539

- ^ The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, "Why Don't Mormons Have Paid Clergy?" Archived 2014-05-08 at the Wayback Machine, mormon.org.

- ^ "The Augsburg Confession". www.gutenberg.org. Archived from the original on 2021-06-24. Retrieved 2022-02-07.

- ^ "Power and Primacy of the Pope (1537): Smalcald Theologians". www.projectwittenberg.org. Archived from the original on 2022-02-07. Retrieved 2022-02-07.

- ^ Presbyterian Church (U.S.A.). Book of Order: 2009-2011 (Louisville: Office of the General Assembly), Form of Government, Chapter 6 and 14. See also "Theology and Worship" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2004-03-07.

- ^ www.wisdomlib.org (2018-09-23). "Arcaka: 11 definitions". www.wisdomlib.org. Archived from the original on 2022-09-28. Retrieved 2022-09-28.

- ^ www.wisdomlib.org (2014-08-03). "Purohita: 24 definitions". www.wisdomlib.org. Archived from the original on 2022-09-20. Retrieved 2022-09-18.

- ^ Dubois, Jean Antoine; Beauchamp, Henry King (1897). Hindu Manners, Customs and Ceremonies. Clarendon Press. p. 15. Archived from the original on 2023-12-24. Retrieved 2023-12-24.

- ISBN 978-1-64324-834-9. Archivedfrom the original on 2023-12-24. Retrieved 2023-12-24.

- ^ "Hindu Religious Worker Definitions". Hindu American Foundation. Archived from the original on 24 June 2021. Retrieved 23 June 2021.

- ^ ISBN 9781351512916. Archivedfrom the original on 18 March 2024. Retrieved 5 June 2018.

- ISBN 978-1780744209. Retrieved 4 June 2018.

- ^ "Qurbani Meat Distribution Rules". Muslim Aid. Archived from the original on 2022-08-22. Retrieved 2022-08-22.

- ^ The Muslim Resurgence in Ghana Since 1950: Nathan Samwini - 2003 p151

- ^ Islam and the Ahmadiyya Jamaʻat: History, Belief, Practice, p.93, Simon Ross Valentine, 2008.

- ^ "Orthodox Women To Be Trained As Clergy, If Not Yet as Rabbis". Forward.com. 21 May 2009. Archived from the original on 6 December 2011. Retrieved 3 September 2013.

- ^ "The Cantor". myjewishlearning.com. My Jewish Learning. Archived from the original on 27 September 2010. Retrieved 3 September 2013.

- ^ Klapheck, Elisa. "Regina Jonas". The Shalvi/Hyman Encyclopedia of Jewish Women. Jewish Women's Archive. Archived from the original on April 21, 2019. Retrieved August 30, 2021 – via jwa.org.

- ^ a b c "Making the cut". j., the Jewish News Weekly of Northern California. 3 March 2006. Archived from the original on 25 October 2012. Retrieved 3 September 2013 – via jweekly.com.

- ^ Grandin, Temple (1980). "Problems With Kosher Slaughter". International Journal for the Study of Animal Problems. 1 (6): 375–390. Archived from the original on 2017-01-18. Retrieved 2017-01-17 – via The Humane Society of the United States.

- ^ Vitello, Paul (2 August 2010). "Evidence Grows of Problem of Clergy Burnout". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 9 October 2016. Retrieved 24 February 2017.

- ^ See A. M. Greeley, Priests: A Calling in Crisis (University of Chicago Press, 2004).

Further reading

Clergy in general

- Aston, Nigel. Religion and revolution in France, 1780-1804 (CUA Press, 2000)

- Bremer, Francis J. Shaping New Englands: Puritan Clergymen in Seventeenth-Century England and New England (Twayne, 1994)

- Dutt, Sukumar. Buddhist monks and monasteries of India (London: G. Allen and Unwin, 1962)

- Farriss, Nancy Marguerite. Crown and clergy in colonial Mexico, 1759-1821: The crisis of ecclesiastical privilege (Burns & Oates, 1968)

- Ferguson, Everett. The Early Church at Work and Worship: Volume 1: Ministry, Ordination, Covenant, and Canon (Casemate Publishers, 2014)

- Freeze, Gregory L. The Parish Clergy in Nineteenth-Century Russia: Crisis, Reform, Counter-Reform (Princeton University Press, 1983)

- Haig, Alan. The Victorian Clergy (Routledge, 1984), in England

- Holifield, E. Brooks. God's ambassadors: a history of the Christian clergy in America (Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, 2007), a standard scholarly history

- Lewis, Bonnie Sue. Creating Christian Indians: Native Clergy in the Presbyterian Church (University of Oklahoma Press, 2003)

- Marshall, Peter. The Catholic Priesthood and the English Reformation (Clarendon Press, 1994)

- Osborne, Kenan B. Priesthood: A history of ordained ministry in the Roman Catholic Church (Paulist Press, 1989), a standard scholarly history

- Parry, Ken, ed. The Blackwell Companion to Eastern Christianity (John Wiley & Sons, 2010)

- Sanneh, Lamin. "The origins of clericalism in West African Islam". The Journal of African History 17.01 (1976): 49–72.

- Schwarzfuchs, Simon. A concise history of the rabbinate (Blackwell, 1993), a standard scholarly history

- Zucker, David J. American rabbis: Facts and fiction (Jason Aronson, 1998)

Female clergy

- Amico, Eleanor B., ed. Reader's Guide to Women's Studies ( Fitzroy Dearborn, 1998), pp 131–33; historiography

- Collier-Thomas, Bettye. Daughters of Thunder: Black Women Preachers and Their Sermons (1997).

- Flowers, Elizabeth H. Into the Pulpit: Southern Baptist Women and Power Since World War II (Univ of North Carolina Press, 2012)

- Maloney, Linda M. "Women in Ministry in the Early Church". New Theology Review 16.2 (2013).

- Ruether, Rosemary Radford. "Should Women Want Women Priests or Women-Church?". Feminist Theology 20.1 (2011): 63–72.

- Tucker, Ruth A. and Walter L. Liefeld. Daughters of the Church: Women and Ministry from New Testament Times to the Present (1987), historical survey of female Christian clergy

External links

- Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). . Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- "Church Administration" - The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints.

- Wlsessays.net, Scholarly articles on Christian Clergy from the Wisconsin Lutheran Seminary Library

- University of the West, Buddhist M.Div.

- Naropa University Archived 2007-02-08 at the Wayback Machine, Buddhist M.Div.

- National Association of Christian Ministers, Priesthood of All Believers: Explained and Supported in Scripture