Climate change vulnerability

Climate change vulnerability is a concept that describes how strongly people or ecosystems are likely to be affected by climate change. Its formal definition is the "propensity or predisposition to be adversely affected" by climate change. It can apply to humans and also to natural systems (or ecosystems).[1]: 12 Issues around the capacity to cope and adapt are also part of this concept.[1]: 5 Vulnerability is a component of climate risk. Vulnerability differs within communities and also across societies, regions, and countries. It can increase or decrease over time.[1]: 12

Vulnerability is higher in some locations than in others. Certain regional factors increase vulnerability, namely

Vulnerability can be grouped into two overlapping categories. Firstly, there is economic vulnerability which is based on

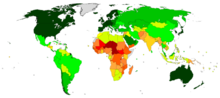

Global vulnerability assessments use spatial mapping with aggregated data for the regional or national level.[2]: 1195–1199 Tools for vulnerability assessment vary depending on the sector, the scale and the entity or system which is thought to vulnerable. For example, the Vulnerability Sourcebook is a guide for practical and scientific knowledge on vulnerability assessment.[3] Climate vulnerability mapping helps to understand which areas are the most vulnerable. Mapping can also help to communicate climate vulnerability to stakeholders.[4] It is useful to carry out vulnerability assessments in advance of preparing local climate adaptation plans or risk management plans.[5]

Definition

Climate change vulnerability is defined as the "propensity or predisposition to be adversely affected" by climate change. It can apply to humans but also to natural systems (ecosystems), and both are interdependent.[1]: 12 Vulnerability is a component of climate risk. Vulnerability will be higher if the capacity to cope and adapt is low.[1]: 5

Climate vulnerability can include a wide variety of different meanings, situations, and contexts in climate change research, and has been a central concept in academic research since 2005.

The concept was defined in the third IPCC report in 2007 as "the degree to which a system is susceptible to, and unable to cope with, adverse effects of climate change, including climate variability and extremes".[8]: 89 The IPCC Sixth Assessment Report in 2022 stated that "approaches to analysing and assessing vulnerability have evolved since previous IPCC assessments".[1]: 5

In the context of political economy, vulnerability is defined as “the state of individuals, groups or communities in terms of their ability to cope with and adapt to any external stress placed on their livelihoods and well-being.”[9] Vulnerability is a relative concept, not an absolute one, meaning that "some people are less or more susceptible than others, at different times and places".[9]

Research in this area focuses on analysing the factors that "put people and places at risk and reduce capacity to respond".[10]

Types

Vulnerability can be grouped into two overlapping categories: economic vulnerability, based on

Economic vulnerability

At its basic level, a community that is economically vulnerable is one that is ill-prepared for the effects of climate change because it lacks the needed financial resources.[11] Preparing a climate resilient society will require huge[quantify] investments in infrastructure, city planning, engineering sustainable energy sources, and preparedness systems.[clarification needed] From a global perspective, it is more likely that people living at or below poverty will be affected the most by climate change and are thus the most vulnerable, because they will have the least amount of resource dollars to invest in resiliency infrastructure. They will also have the least amount of resource dollars for cleanup efforts after more frequently occurring natural climate change related disasters.[12]

Vulnerability of ecosystems and people to climate change is driven by certain

Societal vulnerability to climate change is largely dependent on development status.[13]: 336 Developing countries lack the necessary financial resources to relocate those living in low-lying coastal zones, making them more vulnerable to climate change than developed countries.[14]: 317

Geographic vulnerability

A second definition of vulnerability relates to geographic vulnerability. The most geographically vulnerable locations to climate change are those that will be impacted by side effects of natural hazards, such as rising sea levels and by dramatic changes in ecosystem services, including access to food. Island nations are usually noted as more vulnerable but communities that rely heavily on a sustenance based lifestyle are also at greater risk.[15]

Vulnerable communities tend to have one or more of these characteristics:[16] food insecure, water is scarce, delicate marine ecosystem, fish dependent, small island community.

Around the world, climate change affects rural communities that heavily depend on their agriculture and natural resources for their livelihood. Increased frequency and severity of climate events disproportionately affects women, rural, dryland, and island communities.[17] This leads to more drastic changes in their lifestyles and forces them to adapt to this change. It is becoming more important for local and government agencies to create strategies to react to change and adapt infrastructure to meet the needs of those impacted. Various organizations work to create adaptation, mitigation, and resilience plans that will help rural and at risk communities around the world that depend on the earth's resources to survive.[18]

Scale

It has been estimated in 2021 that "approximately 3.3 to 3.6 billion people live in contexts that are highly vulnerable to climate change".[1]: 12

The vulnerability of ecosystems and people to climate change is not the same everywhere: there are marked differences among and within regions (see regions that are particularly vulnerable below).[1]: 12 Vulnerability can also increase or decrease over time.[1]: 5

People who are more vulnerable

People who are more vulnerable to the effects of climate change than others include for example people with low incomes, indigenous peoples, women, children, the elderly. For example, when looking at the effects of climate change on human health, a report published in The Lancet found that the greatest impact tends to fall on the most vulnerable people such as the poor, women, children, the elderly, people with pre-existing health concerns, other minorities and outdoor workers.[19]

Climate change does not affect people within communities in the same way. It can have a bigger impact on vulnerable groups such as women, the elderly, religious minorities and refugees than on others.[20]

- People living in poverty: Climate change disproportionally affects poor people in low-income communities and developing countries around the world. Those in poverty have a higher chance of experiencing the ill-effects of climate change, due to their increased exposure and vulnerability.[21] A 2020 World Bank paper estimated that between 32 million to 132 million additional people will be pushed into extreme poverty by 2030 due to climate change.[22]

- Women: Climate change increases gender inequality.[23] It reduces women's ability to be financially independent,[24] and has an overall negative impact on the social and political rights of women. This is especially the case in economies that are heavily based on agriculture.[23]

- Indigenous peoples: Indigenous communities tend to rely more on the environment for food and other necessities. This makes them more vulnerable to disturbances in ecosystems.[25] Indigenous communities across the globe generally have bigger economic disadvantages than non-indigenous communities. This is due to the oppression they have experienced. These disadvantages include less access to education and jobs and higher rates of poverty. All this makes them more vulnerable to climate change.[26]

- Children: The Lancet review on health and climate change lists children among the worst-affected by global warming.[27] Children are 14–44 percent more likely to die from environmental factors.[28]

Causes

There can be "structural deficits related to social, economic, cultural, political, and institutional conditions" which would explain why some parts of the population are impacted more than others.[10] This applies for example to climate-related risks to household water security for women in remote rural regions in Burkina Faso[10] or the urban poor in sub-Saharan Africa.[9]

Vulnerability for people of a certain gender or age can be caused by "systemic reproduction of historical legacies of inequality", for example as part of "(post)colonial, (post)apartheid, and poverty discrimination".[9] Social vulnerability of people can be related to aspects that make people different from one another (gender, class, race, age, etc.), and also the situational variables (where they live, their health, who lives with them in the household, how much they earn).[9]

Reducing vulnerability

Vulnerability can be reduced through climate change adaptation measures.[1]: 5 For this reason, vulnerability is often framed in dialogue with climate change adaptation. Furthermore, measures that reduce poverty, gender inequality, bad governance and violent conflict would also reduce vulnerability. And finally, vulnerability would be reduced for everyone if decisive action on climate change was taken (climate change mitigation) so that the effects of climate change are less severe.[citation needed]

Climate change adaptation

Climate resilience

Climate justice

Equity is another essential component of vulnerability and is closely tied to issues of environmental justice and climate justice. As the most vulnerable communities are likely to be the most heavily impacted, a climate justice movement is coalescing in response. There are many aspects of climate justice that relate to vulnerability and resiliency. The frameworks are similar to other types of justice movements and include contractarianism which attempts to allocate the most benefits for the poor, utilitarianism which seeks to find the most benefits for the most people, egalitarianism which attempts to reduce inequality, and libertarianism which emphasizes a fair share of burden but also individual freedoms.[33]

Examples of climate justices approach can be seen by the work done by the United States government on both federal and local levels. On a federal level, The Environmental Protection Agency works toward the goals of Executive Order 12898,[34] Federal Actions to Address Environmental Justice in Minority Populations and Low-Income Populations. E.O 12898 states the goals of implementing federal environmental justice initiatives that work toward aiding minority and low-income communities that suffer from disproportionate environmental or human health impacts. To alleviate environmental and health challenges within many American communities the U.S Environmental Protection Agency has implemented projects[35] region by region to ensure the development of environmental justice. These developments include but are not limited to population vulnerability, green space development locally as well as federally, and the reevaluation of environmentally disproportionate health burdens.

Climate Vulnerable Forum

Measurement tools

Vulnerability assessment is important because it provides information that can be used to develop management actions in response to climate change.[40] Climate change vulnerability assessments and tools are available at all scales. Macro-scale vulnerability assessment often uses indices. Modelling and participatory approaches are also in use. Global vulnerability assessments are based on spatial mapping using aggregated data for the regional or national level.[2]: 1195–1199

Assessments are also done at sub-national and sectoral level, and also increasingly for cities on an

Indicators and indices

Global indices for climate change vulnerability include the

Climate vulnerability tracking starts identifying the relevant information, preferably open access, produced by state or international bodies at the scale of interest. Then a further effort to make the vulnerability information freely accessible to all development actors is required.[45] Vulnerability tracking has many applications. It constitutes an indicator for the monitoring and evaluation of programs and projects for resilience and adaptation to climate change. Vulnerability tracking is also a decision making tool in regional and national adaptation policies.[45]

Tools for vulnerability assessment

Similarly as for

By region

All regions of the world are vulnerable to climate change but to a different degree. With high confidence, researchers concluded in 2001 that developing countries would tend to be more vulnerable to climate change than developed countries.[46]: 957–958 Based on development trends in 2001, scientists have found that few developing countries would have the capacity to efficiently adapt to climate change.[47]: 957 This was partly due to their low adaptive capacity and the high costs of adaptation in proportion to their GDP.

In comparison, the climate vulnerability of Europe is lower than in developing countries. This was attributed to Europe's high GNP, stable growth, stable population, and well-developed political, institutional, and technological support systems.[48]: 643

Examples for vulnerability and adaptive capacity by region include:

- Africa: Africa's major economic sectors are vulnerable to observed climate variability. As a result, Africa's vulnerability to future climate change is projected to be significantly high. An estimated sea-level rise of 0.48m[49] puts coastal cities such as Dar es Salaam, Bagamoyo, Lagos, Cotonou, Porto-Novo, Cairo, and Alexandria at risk of permanent flooding as well as threatening the well-being of natural resources such as marine life. Africa’s decline in agricultural productivity by 34% since 1961 due to climate and lacking economic access to sufficient food puts about 50%[50] of its citizens under what’s known as food stress. Additionally, Article Camber Collective linked that temperature rise would increase the brewing of infectious diseases carried by mosquitoes and ticks; heightening the transmission of malaria, dengue fever, and Lyme disease.[51] Natural disasters including droughts, earthquakes, water scarcity, and heat waves have also adversely affected the livelihood of those from lower-income communities disproportionately claiming at least 15,700 lives.[52]

- Asia: Climate change can result in the degradation of permafrost in boreal Asia. This makes climate-dependent sectors more vulnerable to the affect of the region's economy.[53]: 536 The World Meteorological Organization states that degradation is a main factor in the increase of droughts and floods hitting asian regions, being one of the main causes of loss of life and economic damage in countries like Pakistan, Japan, China, and India.[54] The Sherpas a South Asian indigenous group is particularly vulnerable to climate change. Living in the high Himalayas hazards such as lake outbursts, landslides, avalanches, floods, and droughts have made an impact on their livelihood like survival and funds. With warmer weather becoming more common traditional jobs such as herding and cultivating food have become less common due to unstable livestock and crop conditions as well as guiding due to drops in tourism.[55]

- Australia and New Zealand: In Australia and New Zealand, some indigenous communities were judged to have a higher level of vulnerability and low adaptive capacity.[56]: 509 For example, the Aboriginal Australian population lives predominantly in three biome types which will directly impact their well-being with the onslaught of climate change. Those who don't live on the coast live in either desert or savanna biomes which will be severely impacted by the increasing temperatures brought on by climate change. Additionally, for those Aboriginals who live on the coast, they will be impacted greatly by sea level rise.[57] Overall, these communities will struggle significantly more than their non-native counterparts as they struggle to adapt especially as they don't have as much financial support to do so. Aboriginals make $771[58] per week, whereas non-natives make $1,888.80.[59]

- Europe: Scientists judged the adaptation potential of socioeconomic systems in Europe as relatively high in 2001. This is due to Europe's high GNP, stable growth, stable population, and well-developed political, institutional, and technological support systems. According to an article[1] by the European Environmental Agency, most of what Europe expects to deal with involves natural disasters such as floods and heat waves. The EEA reported that heatwaves have so far been their largest cause of fatalities and storms/floods cause the most property damage. However, not all communities are benefitting. An example is the Romani people who suffer greatly from environmental racism. In a report[2] by the European Environmental Bureau, statistics show that 154,000 Romani have been impacted by forms of environmental racism varying from limiting water access, to forced displacement, and insufficient sanitation.

- Latin America: With the deforestation of the world's largest rainforest, South America is taking a punch to the gut when it comes to receiving more CO2 emissions. It is important to recognize those who will become the most affected by the variability climate change will instill in the most vulnerable communities. In Latin America, there are 42 million indigenous people with 43% being impacted by poverty, according to a report[1] by the World Bank. Depending on the region, the disparities caused by the wealth gap could impact these indigenous groups in Latin America if their lives are disrupted by climate change. In an article[2] by Johns Hopkins University, only 7% of issued global funds actually reach the indigenous groups selected for financial support. The lack of funding, on top of environmental racism, is a huge issue facing these communities. An example comes from Ecuador, where the Ecuadorian government has "given over 148 new concessions for gold mines in the Napo province" which pollute the waters used by the Napo province's indigenous people.

The Flint Water Crisis (2014) in Flint, Michigan represents an intersection of injustice and climate change impacts we can expect to see. With climate change setting in, water access will become increasingly scarce, and if available, not filtered in many communities. - North America: Due to North America's vastness, different areas of the continent will receive different climate change impacts. This includes increased drought, vulnerability to extreme weather events, and decreases in crop yield. For example, Native Alaskans have proven to already suffer from the early onset of climate change impacts. Native Alaskans have been forced to live in vulnerable areas due to federal land allotment, according to the United States Department of Agriculture. This has forced them to live in areas increasingly vulnerable to climate change impacts and decreasing access to First Foods, the types of food that indigenous Alaskans have been eating for centuries. Namely, the Chinook salmon, which has become endangered due to overfishing.

- Arctic: The Arctic is extremely vulnerable to climate change. It was predicted in 2007 that there would be major ecological, sociological, and economic impacts in the region.[60]: 804–805 Among those being disproportionately impacted by issues regarding climate change have been the Indigenous peoples of the Arctic, such as the Inuit, Yupik, and Saami, whom are particularly vulnerable.[61] Traditional livelihoods, including hunting, fishing, and reindeer herding, are threatened by changes in ice conditions, wildlife migration patterns, and habitat availability. Additionally, melting permafrost can damage infrastructure and contaminate water sources, posing health and safety risks to communities. The thawing of permafrost also releases greenhouse gases such as methane and carbon dioxide,[62] contributing to further warming and climate change, ultimately destabilizing infrastructure built on permafrost, such as buildings, roads, and pipelines.

- Small island Developing States are particularly vulnerable to climate change.[63]: 689 Partly this was attributed to their low adaptive capacity and the high costs of adaptation in proportion to their GDP. Climate change leads to more frequent and intense extreme weather events such as hurricanes, typhoons, and cyclones. Small islands are especially susceptible to these events, which can cause widespread destruction, loss of life, and economic setbacks. Rebuilding after such events can strain already limited resources.

By country

See also

References

- ^

- ^

- ^ a b Fritzsche, K., Schneiderbauer, S., Buseck, P., Kienberger, S., Buth, M., Zebisch, M. and Kahlenborn, W. (2017). The Vulnerability Sourcebook Archived 2023-05-18 at the Wayback Machine. Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) GmbH.

- ^ ISSN 1757-7799.

- ^ ISBN 978-3-319-59095-0.

- ^ Füssel, Hans-Martin (2005-12-01). "Vulnerability in Climate Change Research: A Comprehensive Conceptual Framework". Archived from the original on 2021-04-17. Retrieved 2020-12-26.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ IPCC (2007a). "Climate Change 2007: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (Core Writing Team, Pachauri, R.K and Reisinger, A. (eds.))". IPCC, Geneva, Switzerland. Archived from the original on 2018-11-02. Retrieved 2009-05-20.

- ^ ISSN 2049-1948.

- ^ ISSN 1756-5529.

- S2CID 247956525.

- ^ M.J. Collier et al. "Transitioning to resilience and sustainability in urban communities" Cities 2013. 32:21–S28

- ISBN 978-0-521-88010-7. Archived from the originalon 2 May 2010. Retrieved 2010-05-23.

- ISBN 978-0-521-88010-7. Archived from the originalon 2 May 2010. Retrieved 2010-05-23.

- ^ K. Hewitt (Ed.), Interpretations of Calamity for the Viewpoint of Human Ecology, Allen and Unwin, Boston (1983), pp. 231–262

- ^ Kasperson, Roger E., and Jeanne X. Kasperson. Climate change, vulnerability, and social justice. Stockholm: Stockholm Environment Institute, 2001.

- ^ "Climate Change". Natural Resources Institute. Archived from the original on 2021-05-11. Retrieved 2020-08-09.

- ^ "Achieving Dryland Women's Empowerment: Environmental Resilience and Social Transformation Imperatives" (PDF). Natural Resources Institute. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2021-05-11. Retrieved 2020-08-09.

- (PDF) from the original on 2023-04-07. Retrieved 2023-05-17.

- ^ Begum, Rawshan Ara; Lempert, Robert; et al. "Chapter 1: Point of Departure and Key Concept" (PDF). Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. The Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge University Press. p. 170.

- .

- ^ "Revised Estimates of the Impact of Climate Change on Extreme Poverty by 2030" (PDF). September 2020.

- ^ S2CID 89614518.

- S2CID 216404045.

- ^ Pörtner, H.-O.; Roberts, D.C.; Adams, H.; Adelekan, I.; et al. "Technical Summary" (PDF). Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. The Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge University Press. p. 47.

- PMID 22594718.

- S2CID 207976337.

- S2CID 55860349.

- ^

- ^ IPCC, 2022: Summary for Policymakers [H.-O. Pörtner, D.C. Roberts, E.S. Poloczanska, K. Mintenbeck, M. Tignor, A. Alegría, M. Craig, S. Langsdorf, S. Löschke, V. Möller, A. Okem (eds.)]. In: Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [H.-O. Pörtner, D.C. Roberts, M. Tignor, E.S. Poloczanska, K. Mintenbeck, A. Alegría, M. Craig, S. Langsdorf, S. Löschke, V. Möller, A. Okem, B. Rama (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK and New York, NY, USA, pp. 3–33, doi:10.1017/9781009325844.001.

- ISSN 2059-7037. Text was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

- ^ Liu, F. (2000). Environmental justice analysis: Theories, methods and practice. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press

- ^ US EPA, OP (2013-02-22). "Summary of Executive Order 12898 - Federal Actions to Address Environmental Justice in Minority Populations and Low-Income Populations". www.epa.gov. Retrieved 2024-02-06.

- ^ US EPA, OEJECR (2015-04-15). "Environmental Justice in Your Community". www.epa.gov. Retrieved 2024-02-06.

- ^ "About". Climate Vulnerable Forum. 2021. Retrieved 2022-07-16.

- ^ a b "Climate Vulnerable Forum Declaration adopted - DARA".

- ^ "Nasheed asks: "Will our culture be allowed to die out?"". ENDS Copenhagen Blog. Archived from the original on November 10, 2014.

- ^ "CVF Declaration" (PDF).

- ^ "Climate Change Vulnerability Assessments | Climate Change Resource Center". www.fs.usda.gov. Archived from the original on 2022-10-04. Retrieved 2022-10-04.

- ^ "Fiji: Climate Vulnerability Assessment". Global Facility for Disaster Reduction and Recovery. 2017. Archived from the original on 2021-01-21. Retrieved 2020-12-26.

- ^ "Climate vulnerability assessment". City of Rochester NY. Archived from the original on 2020-10-31. Retrieved 2020-12-26.

- ^ "Climate Vulnerability Assessments". NOAA Fisheries. 2019-09-19. Archived from the original on 2021-03-23. Retrieved 2020-12-26.

- ^ INFORM (2019), DRMKC - INFORM Archived 2023-05-18 at the Wayback Machine, European Commission Joint Research Center. Available at: https://drmkc.jrc.ec.europa.eu/inform-index/ Results/Global

- ^ .

- ^ Smith, J. B.; et al. (2001). "Vulnerability to Climate Change and Reasons for Concern: A Synthesis. In: Climate Change 2001: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Third Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (J.J. McCarthy et al. Eds.)". Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK, and New York, N.Y. Archived from the original on 2018-10-05. Retrieved 2010-01-10.

- ^ Smith, J. B.; et al. (2001). "19. Vulnerability to Climate Change and Reasons for Concern: A Synthesis" (PDF). In McCarthy, J. J.; et al. (eds.). Climate Change 2001: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Third Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (PDF). Cambridge, UK, and New York, N.Y.: Cambridge University Press. pp. 913–970. Retrieved 2022-01-19.

- ^ Kundzewicz, Z. W.; et al. (2001). J. J. McCarthy; et al. (eds.). "Europe. In: Climate Change 2001: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Third Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change". Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK, and New York, N.Y. Archived from the original on 27 April 2012. Retrieved 2010-01-10.

- ^ "United Nations Economic Commission for Africa (UNECA)/Nations Unies commission économique pour l'Afrique (CEA)". African Studies Companion Online. Retrieved 2024-04-18.

- ^ Digital, AGRF (2023-09-05). "2023 Africa Agriculture Status Report Released - AGRF". Retrieved 2024-04-18.

- ^ Kennedy, Rozella (2023-03-07). "Climate Change and Infectious Disease in Africa". Camber Collective. Retrieved 2024-04-18.

- ^ "Rising climate death toll in Africa underscores urgency for COP28 action - World | ReliefWeb". reliefweb.int. 2023-11-28. Retrieved 2024-04-18.

- ^ Lal, M.; et al. (2001). "11. Asia" (PDF). In McCarthy, J. J.; et al. (eds.). Climate Change 2001: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Third Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (PDF). Cambridge, UK, and New York, N.Y.: Cambridge University Press. pp. 533–590. Retrieved 2022-01-19.

- ^ "Climate change impacts increase in Asia". World Meteorological Organization. 2023-07-26. Retrieved 2024-03-21.

- ^ "Sherpas and Climate Change | Aksik". www.aksik.org. Retrieved 2024-04-18.

- ^ Hennessy, K.; et al. (2007). M. L. Parry; et al. (eds.). "Australia and New Zealand. In: Climate Change 2007: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change". Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK, and New York, N.Y. pp. 507–540. Archived from the original on 19 January 2010. Retrieved 2009-05-20.

- ^ CSIRO. "Climate projections for Australia". www.csiro.au. Retrieved 2024-03-19.

- ^ "Regional overview". AIHW RIFIC. Retrieved 2024-03-18.

- ^ "Average Weekly Earnings, Australia, November 2023 | Australian Bureau of Statistics". www.abs.gov.au. 2024-02-22. Retrieved 2024-03-18.

- ISBN 978-0-521-80768-5. Retrieved 2022-01-19.

- ^ Vo, Steven (2021-02-23). "Indigenous Peoples and Climate Justice in the Arctic". Georgetown Journal of International Affairs. Retrieved 2024-04-18.

- ^ "Thawing permafrost". WWF Arctic (in Swedish). Retrieved 2024-04-18.

- ISBN 978-0-521-88010-7. Archivedfrom the original on 2011-10-14. Retrieved 2010-05-23.