Clostridioides difficile infection

| Clostridioides difficile infection | |

|---|---|

| Other names | C. difficile associated diarrhea (CDAD), Clostridium difficile infection, C. difficile colitis |

| Frequency | 453,000 (US 2011)[2][4] |

| Deaths | 29,000 (US)[2][4] |

Clostridioides difficile infection

Clostridioides difficile infection is spread by bacterial spores found within

Prevention efforts include

The antibiotics

C. difficile infections occur in all areas of the world.[11] About 453,000 cases occurred in the United States in 2011, resulting in 29,000 deaths.[2][4] Global rates of disease increased between 2001 and 2016.[2][11] C. difficile infections occur more often in women than men.[2] The bacterium was discovered in 1935 and found to be disease-causing in 1978.[11] Attributable costs for Clostridioides difficile infection in hospitalized adults range from

$4500 to $15,000.

Signs and symptoms

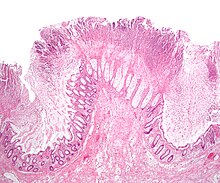

Signs and symptoms of CDI range from mild diarrhea to severe life-threatening inflammation of the colon.[16]

In adults, a

In children, the most prevalent symptom of a CDI is watery diarrhea with at least three bowel movements a day for two or more days, which may be accompanied by fever, loss of appetite, nausea, and/or abdominal pain.[19] Those with a severe infection also may develop serious inflammation of the colon and have little or no diarrhea.[citation needed]

Cause

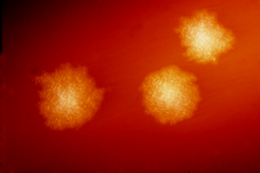

Infection with

C. difficile

Clostridia are

C. difficile may colonize the human colon without symptom; approximately 2–5% of the adult population are carriers, although it varies considerably with demographics.[20] The risk of colonization has been linked to a history of unrelated diarrheal illnesses (e.g. laxative abuse and food poisoning due to Salmonellosis or Vibrio cholerae infection).[15]

Pathogenic C. difficile strains produce multiple

Antibiotic treatment of CDIs may be difficult, due both to

C. difficile is transmitted from person to person by the

In 2005, molecular analysis led to the identification of the C. difficile strain type characterized as group BI by restriction endonuclease analysis, as North American pulse-field-type NAP1 by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis and as ribotype 027; the differing terminology reflects the predominant techniques used for epidemiological typing. This strain is referred to as C. difficile BI/NAP1/027.[26]

Risk factors

Antibiotics

C. difficile colitis is associated most strongly with the use of these antibiotics:

Some research suggests the routine

Healthcare environment

People are most often infected in hospitals, nursing homes,[29] or other medical institutions, although infection outside medical settings is increasing. Individuals can develop the infection if they touch objects or surfaces that are contaminated with feces and then touch their mouth or mucous membranes. Healthcare workers could possibly spread the bacteria or contaminate surfaces through hand contact.[30] The rate of C. difficile acquisition is estimated to be 13% in those with hospital stays of up to two weeks, and 50% with stays longer than four weeks.[31]

Long-term hospitalization or residence in a nursing home within the previous year are independent risk factors for increased colonization.[32]

Acid suppression medication

Increasing rates of community-acquired CDI are associated with the use of medication to suppress

Diarrheal illnesses

People with a recent history of diarrheal illness are at increased risk of becoming colonized by C. difficile when exposed to spores, including laxative abuse and gastrointestinal pathogens.[15] Disturbances that increase intestinal motility are thought to transiently elevate the concentration of available dietary sugars, allowing C. difficile to proliferate and gain a foothold in the gut.[36] Although not all colonization events lead to disease, asymptomatic carriers remain colonized for years at a time.[15] During this time, the abundance of C. difficile varies considerably day-to-day, causing periods of increased shedding that could substantially contribute to community-acquired infection rates.[15]

Other

As a result of suppression of healthy bacteria, via a loss of bacterial food source, prolonged use of an elemental diet increases the risk of developing C. difficile infection.[37] Low serum albumin levels is a risk factor for the development of C. difficile infection and when infected for severe disease.[38][39] The protective effects of serum albumin may be related to the capability of this protein to bind C. difficile toxin A and toxin B, thus impairing entry into enterocytes.[39]

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) has been identified as a risk factor in the development of a C. difficile infection.[40][41] Patients with CKD have a higher risk of both initial and recurring infection, as well as a higher chance of severe infection, than those without CKD.[42] Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease are also at higher risk for infection and a recent study suggests they may have intermittent C. difficile infection masked by IBD symptoms, and testing should be considered in patients with changes in disease activity.[43]

Pathophysiology

The use of systemic antibiotics, including broad-spectrum penicillins/cephalosporins, fluoroquinolones, and clindamycin, causes the normal microbiota of the bowel to be altered. In particular, when the

Diagnosis

Prior to the advent of tests to detect C. difficile toxins, the diagnosis most often was made by

Classification

CDI may be classified in non-severe CDI, severe CDI and fulminant CDI depending on creatinine and white blood count parameters.[47]

Cytotoxicity assay

C. difficile toxins have a

Toxin ELISA

Assessment of the A and B toxins by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (

Previously, experts recommended sending as many as three stool samples to rule out disease if initial tests are negative, but evidence suggests repeated testing during the same episode of diarrhea is of limited value and should be discouraged.[49] C. difficile toxin should clear from the stool of somebody previously infected if treatment is effective. Many hospitals only test for the prevalent toxin A. Strains that express only the B toxin are now present in many hospitals, however, so testing for both toxins should occur.[50][51] Not testing for both may contribute to a delay in obtaining laboratory results, which is often the cause of prolonged illness and poor outcomes.[citation needed]

Other stool tests

Stool

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR)

Testing of stool samples by real-time polymerase chain reaction is able to detect C. difficile about 93% of the time and when positive is incorrectly positive about 3% of the time.[53] This is more accurate than cytotoxigenic culture or cell cytotoxicity assay.[53] Another benefit is that the result can be achieved within three hours.[53] Drawbacks include a higher cost and the fact that the test only looks for the gene for the toxin and not the toxin itself.[53] The latter means that if the test is used without confirmation, overdiagnosis may occur.[53] Repeat testing may be misleading, and testing specimens more than once every seven days in people without new symptoms is highly unlikely to yield useful information.[54] The screening specificity is relatively low because of the high number of false positive cases from asymptomatic infection.[46]

Prevention

Self containment by housing people in private rooms is important to prevent the spread of C. difficile.[55] Contact precautions are an important part of preventing the spread of C. difficile. C. difficile does not often occur in people who are not taking antibiotics so limiting use of antibiotics decreases the risk.[56]

Antibiotics

The most effective method for preventing CDI is proper

Probiotics

Some evidence indicates

One study in particular found that there does appear to be a "protective effect" of probiotics, specifically reducing the risk of antibiotic-associated diarrhea (AAD) by 51% in 3,631 outpatients, but it is important to note that the types of infections in the subjects were not specified.[64] Yogurt, tablets, dietary supplements are just a few examples of probiotics available for people.[citation needed]

Infection control

Rigorous infection protocols are required to minimize this risk of transmission.[65] Infection control measures, such as wearing gloves and noncritical medical devices used for a single person with CDI, are effective at prevention.[66] This works by limiting the spread of C. difficile in the hospital setting. In addition, washing with soap and water will wash away the spores from contaminated hands, but alcohol-based hand rubs are ineffective.[67] These precautions should remain in place among those in hospital for at least 2 days after the diarrhea has stopped.[68]

Bleach wipes containing 0.55% sodium hypochlorite have been shown to kill the spores and prevent transmission.[69] Installing lidded toilets and closing the lid prior to flushing also reduces the risk of contamination.[70]

Those who have CDIs should be in rooms with other people with CDIs or by themselves when in hospital.[66]

Common hospital

Treatment

Carrying C. difficile without symptoms is common. Treatment in those without symptoms is controversial. In general, mild cases do not require specific treatment.[3][20] Oral rehydration therapy is useful in treating dehydration associated with the diarrhea.[citation needed]

Medications

Several different antibiotics are used for C. difficile, with the available agents being more or less equally effective.[75]

Vancomycin or fidaxomicin by mouth are the typically recommended for mild, moderate, and severe infections.[76] They are also the first-line treatment for pregnant women, especially since metronidazole may cause birth defects.[77] Typical vancomycin 125mg is taken four times a day by mouth for 10 days.[77][47] Fidaxomicin is taken at 200 mg twice daily for 10 days.[47] It may also be given rectally if the person develops an ileus.[76]

Fidaxomicin is tolerated as well as vancomycin,

Medications used to slow or stop diarrhea, such as loperamide, may only be used after initiating the treatment.[47]

Probiotics

Evidence to support the use of probiotics in the treatment of active disease is insufficient.[61][83][84][85] Researchers have recently begun taking a mechanical approach to fecal-derived products. It is known that certain microbes with 7α-dehydroxylase activity can metabolize primary to secondary bile acids, which inhibit C. difficile. Thus, incorporating such microbes into therapeutic products such as probiotics may be protective, although more pre-clinical investigations are needed.[86]

Fecal microbiota transplantation

Fecal microbiota transplant, also known as a stool transplant, is roughly 85% to 90% effective in those for whom antibiotics have not worked.[87][88][89] It involves infusion of the microbiota acquired from the feces of a healthy donor to reverse the bacterial imbalance responsible for the recurring nature of the infection.[90] The procedure replenishes the normal colonic microbiota that had been wiped out by antibiotics, and re-establishes resistance to colonization by Clostridioides difficile.[91] Side effects, at least initially, are few.[89]

Surgery

In those with severe C. difficile colitis, colectomy may improve the outcomes.[96] Specific criteria may be used to determine who will benefit most from surgery.[97]

Recurrent infection

Recurrent CDI occurs in 20 to 30% of the patients, with increasing rates of recurrence with each subsequent episode.[98] In clinical settings, it is virtually impossible to distinguish a recurrence that develops as a relapse of CDI with the same strain of C. difficile versus reinfection that is the result of a new strain.[citation needed] However, in labratory settings paired isolates can be differentiated using Whole-Genome Sequencing or Multilocus Variable-Number Tandem-Repeat Analysis.[99]

Several treatment options exist for recurrent C difficile infection. For the first episode of recurrent C difficile infection, the 2017 IDSA guidelines recommend oral vancomycin at a dose of 125 mg four times daily for 10 days if metronidazole was used for the initial episode. If oral vancomycin was used for the initial episode, then a prolonged oral vancomycin pulse dose of 125 mg four times daily for 10-14 days followed by a taper (twice daily for one week, then every two to three days for 2-8 weeks) or fidaxomicin 200 mg twice daily for 10 days. For a second recurrent episode, the IDSA recommends options including the aforementioned oral vancomycin pulse dose followed by the prolonged taper; oral vancomycin 125 mg four times daily for 10 days followed by rifaximin 400 mg three times daily for 20 days; fidaxomicin 200 mg twice daily for 10 days, or a fecal microbiota transplant.[80]

For patients with C. diff infections that fail to be resolved with traditional antibiotic regimens, fecal microbiome transplants boasts an average cure rate of >90%.[100] In a review of 317 patients, it was shown to lead to resolution in 92% of the persistent and recurrent disease cases.[101] It is clear that restoration of gut flora is paramount in the struggle against recurrent CDI. With effective antibiotic therapy, C. difficile can be reduced and natural colonization resistance can develop over time as the natural microbial community recovers. Reinfection or recurrence may occur before this process is complete. Fecal microbiota transplant may expedite this recovery by directly replacing the missing microbial community members.[102] However, human-derived fecal matter is difficult to standardize and has multiple potential risks, including the transfer of infectious material and long-term consequences of inoculating the gut with a foreign fecal material. As a result, further research is necessary to study the long term effective outcomes of FMT.[citation needed]

Prognosis

After a first treatment with metronidazole or vancomycin, C. difficile recurs in about 20% of people. This increases to 40% and 60% with subsequent recurrences.[103]

Epidemiology

C. difficile diarrhea is estimated to occur in eight of 100,000 people each year.[104] Among those who are admitted to hospital, it occurs in between four and eight people per 1,000.[104] In 2011, it resulted in about half a million infections and 29,000 deaths in the United States.[4]

Due in part to the emergence of a

History

Ivan C. Hall and Elizabeth O'Toole first named the bacterium Bacillus difficilis in 1935, choosing its specific epithet because it was resistant to early attempts at isolation and grew very slowly in culture.[103][107] André Romain Prévot subsequently transferred it to Clostridium, binomen Clostridium difficile.[108][109] Its combination was later changed to Clostridioides difficile after being transferred to the new genus Clostridioides.[110]

Pseudomembranous colitis first was described as a complication of C. difficile infection in 1978,[111] when a toxin was isolated from people with pseudomembranous colitis and Koch's postulates were met.

Notable outbreaks

- On 4 June 2003, two outbreaks of a highly virulent strain of this bacterium were reported in Calgary, Alberta. Sources put the death count to as low as 36 and as high as 89, with around 1,400 cases in 2003 and within the first few months of 2004. CDIs continued to be a problem in the Quebec healthcare system in late 2004. As of March 2005, it had spread into the Toronto area, hospitalizing 10 people. One died while the others were being discharged.[citation needed]

- A similar outbreak took place at Stoke Mandeville Hospital in the United Kingdom between 2003 and 2005. The local epidemiology of C. difficile may offer clues on how its spread may relate to the time a patient spends in hospital and/or a rehabilitation center. It also samples the ability of institutions to detect increased rates, and their capacity to respond with more aggressive hand-washing campaigns, quarantine methods, and the availability of yogurt containing live cultures to patients at risk for infection.[citation needed]

- Both the Canadian and English outbreaks possibly were related to the seemingly more virulent strain NAP1/027 of the bacterium. Known as Quebec strain, it has been implicated in an epidemic at two Dutch hospitals (Harderwijk and Amersfoort, both 2005). A theory for explaining the increased virulence of 027 is that it is a hyperproducer of both toxins A and B and that certain antibiotics may stimulate the bacteria to hyperproduce.[citation needed]

- On 1 October 2006, C. difficile was said to have killed at least 49 people at hospitals in Leicester, England, over eight months, according to a National Health Service investigation. Another 29 similar cases were investigated by coroners.[112] A UK Department of Health memo leaked shortly afterward revealed significant concern in government about the bacterium, described as being "endemic throughout the health service"[113]

- On 27 October 2006, nine deaths were attributed to the bacterium in Quebec.[114]

- On 18 November 2006, the bacterium was reported to have been responsible for 12 deaths in Quebec. This 12th reported death was only two days after the St. Hyacinthe's Honoré Mercier announced the outbreak was under control. Thirty-one people were diagnosed with CDIs. Cleaning crews took measures in an attempt to clear the outbreak.[115]

- C. difficile was mentioned on 6,480 death certificates in 2006 in UK.[116]

- On 27 February 2007, a new outbreak was identified at Trillium Health Centre in Mississauga, Ontario, where 14 people were diagnosed with CDIs. The bacteria were of the same strain as the one in Quebec. Officials have not been able to determine whether C. difficile was responsible for the deaths of four people over the prior two months.[117]

- Between February and June 2007, three people at Loughlinstown Hospital in Dublin, Ireland, were found by the coroner to have died as a result of C. difficile infection. In an inquest, the Coroner's Court found the hospital had no designated infection control team or consultant microbiologist on staff.[118]

- Between June 2007 and August 2008, Northern Health and Social Care Trust Northern Ireland, Antrim Area, Braid Valley, Mid Ulster Hospitals were the subject of inquiry. During the inquiry, expert reviewers concluded that C. difficile was implicated in 31 of these deaths, as the underlying cause in 15, and as a contributory cause in 16. During that time, the review also noted 375 instances of CDIs in those being treated at the hospital.[119]

- In October 2007, Maidstone and Tunbridge Wells NHS Trust was heavily criticized by the Healthcare Commission regarding its handling of a major outbreak of C. difficile in its hospitals in Kent from April 2004 to September 2006. In its report, the Commission estimated approximately 90 people "definitely or probably" died as a result of the infection.[120][121]

- In November 2007, the 027 strain spread into several hospitals in southern Finland, with 10 deaths out of 115 infected people reported on 2007-12-14.[122]

- In November 2009, four deaths at Our Lady of Lourdes Hospital in Ireland have possible links to CDI. A further 12 people tested positive for infection, and another 20 showed signs of infection.[123]

- From February 2009 to February 2010, 199 people at Herlev hospital in Denmark were suspected of being infected with the 027 strain. In the first half of 2009, 29 died in hospitals in Copenhagen after they were infected with the bacterium.[124]

- In May 2010, a total of 138 people at four different hospitals in Denmark were infected with the 027 strain [125] plus there were some isolated occurrences at other hospitals.[126]

- In May 2010, 14 fatalities were related to the bacterium in the Australian state of Victoria. Two years later, the same strain of the bacterium was detected in New Zealand.[127]

- On 28 May 2011, an outbreak in Ontario had been reported, with 26 fatalities as of 24 July 2011.[128]

- In 2012/2013, a total of 27 people at one hospital in the south of Sweden (Ystad) were infected with 10 deaths. Five died of the strain 017.[129]

Etymology and pronunciation

The genus name is from the

Regarding the pronunciation of the current and former genus assignments, Clostridioides is /klɒˌstrɪdiˈɔɪdis/ and Clostridium is /klɒˈstrɪdiəm/. Both genera still have species assigned to them, but this species is now classified in the former. Via the norms of binomial nomenclature, it is understood that the former binomial name of this species is now an alias.[citation needed]

Regarding the specific name, /dɪˈfɪsɪli/[132] is the traditional norm, reflecting how medical English usually pronounces naturalized New Latin words (which in turn largely reflects traditional English pronunciation of Latin), although a restored pronunciation of /dɪˈfɪkɪleɪ/ is also sometimes used (the classical Latin pronunciation is reconstructed as [kloːsˈtrɪdɪ.ũː dɪfˈfɪkɪlɛ]). The specific name is also commonly pronounced /ˌdiːfiˈsiːl/, as though it were French, which from a prescriptive viewpoint is a "mispronunciation"[132] but from a linguistically descriptive viewpoint cannot be described as erroneous because it is so widely used among health care professionals; it can be described as "the non-preferred variant" from the viewpoint of sticking most regularly to New Latin in binomial nomenclature, which is also a valid viewpoint, although New Latin specific names contain such a wide array of extra-Latin roots (including surnames and jocular references) that extra-Latin pronunciation is involved anyway (as seen, for example, with Ba humbugi, Spongiforma squarepantsii, and hundreds of others).[citation needed]

Research

- As of 2019, vaccine candidates providing immunity against

- CDA-1 and CDB-1 (also known as MDX-066/MDX-1388 and MBL-CDA1/MBL-CDB1) is an investigational, monoclonal antibody combination co-developed by

- Giardia lamblia) and also is currently being studied in C. difficile infections vs. vancomycin.[139]

- Rifaximin,[139] is a clinical-stage semisynthetic, rifamycin-based, nonsystemic antibiotic for CDI. It is FDA-approved for the treatment of infectious diarrhea and is being developed by Salix Pharmaceuticals.

- Other drugs for the treatment of CDI are under development and include rifalazil,[139] tigecycline,[139] ramoplanin,[139] ridinilazole, and SQ641.[140]

- Research has studied whether the IgA and IgG antibodies, leading to an increased probability of good gut flora surviving against the C. difficile bacteria.[141]

- Taking non-toxic types of C. difficile after an infection has promising results with respect to preventing future infections.[142]

- Treatment with bacteriophages directed against specific toxin-producing strains of C difficile are also being tested.[80]

- A study in 2017 linked severe disease to trehalose in the diet.[143]

Other animals

- Colitis-X (in horses)

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p "Frequently Asked Questions about Clostridium difficile for Healthcare Providers". CDC. 6 March 2012. Archived from the original on 2 September 2016. Retrieved 5 September 2016.

- ^ PMID 27148613.

- ^ PMID 28257555.

- ^ S2CID 20441835.

- ^ Taxonomy. Lawson et al (2016). NCBI. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Taxonomy/Browser/wwwtax.cgi?mode=Info&id=1496&lvl=3&lin=f&keep=1&srchmode=1&unlock

- ISSN 0893-8512.

- PMID 29858434.

- PMID 29868851.

- ISBN 978-1455739851. Archivedfrom the original on 14 September 2016.

- ^ Li W (2019). Eat To Beat Disease. GrandCentral. pp. 44–45, 50–51.

- ^ PMID 22752867.

- PMID 26003403.

- S2CID 2536693.

- PMID 24066741.

- ^ S2CID 211074075.

- PMID 23342416.

- S2CID 3051623.

- PMID 8644759.

- PMID 23733223.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-8385-8529-0.

- PMID 27153087.

- PMID 7883950.

- PMID 15353562.

- S2CID 14818750.

- (PDF) from the original on 4 June 2011.

- S2CID 23376891.

- PMID 25440127.

- ^ "Scientists probe whether C. difficile is linked to eating meat". CBC News. 4 October 2006. Archived from the original on 24 October 2006.

- PMID 28382547.

- ^ "Clostridium difficile Infection Information for Patients | HAI | CDC". www.cdc.gov. Archived from the original on 30 March 2017. Retrieved 19 April 2017.

- PMID 1323621.

- PMID 18387898.

- PMID 20458086.

- PMID 22019794.

- PMID 28346595.

- PMID 25498344.

- PMID 20066732.

- PMID 22752871.

- ^ PMID 30858872.

- ^ "C. difficile-Symptoms and causes". Mayo Clinic. 27 August 2021. Retrieved 23 October 2022.

- PMID 26767866.

- S2CID 80621282.

- PMID 37874904.

- S2CID 4417414.

- ^ "Surgical Pathology Criteria: Pseudomembranous Colitis". Stanford School of Medicine. Archived from the original on 3 September 2014.

- ^ PMID 37389232.

- ^ S2CID 234768271.

- ISBN 978-1-55581-255-3.[page needed]

- PMID 21635969.

- ^ Salleh A (2 March 2009). "Researchers knock down gastro bug myths". ABC Science Online. Archived from the original on 3 March 2009. Retrieved 2 March 2009.

- PMID 19252482.

- ^ S2CID 30286964.

- ^ JOURNAL OF CLINICAL MICROBIOLOGY, October 2010, p. 3738–3741

- ^ "FAQs (frequently asked questions) "Clostridium Difficile"" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 7 December 2016.

- ^ "Clostridium difficile Infection Information for Patients | HAI | CDC". www.cdc.gov. Archived from the original on 16 December 2016. Retrieved 18 December 2016.

- ^ Weiss AJ, Elixhauser A. Origin of Adverse Drug Events in U.S. Hospitals, 2011. HCUP Statistical Brief #158. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Rockville, MD. July 2013. "Origin of Adverse Drug Events in U.S. Hospitals, 2011 - Statistical Brief #158". Archived from the original on 7 April 2016. Retrieved 9 February 2016.

- ^ "PRIME® Continuing Medical Education". primeinc.org. Archived from the original on 6 February 2017.

- ^ S2CID 22813174.

- ^ S2CID 72364505.

- ^ PMID 21992956.

- S2CID 7557917.

- PMID 29257353.

- PMID 29023420.

- ^ "C. difficile infection - Symptoms and causes". Mayo Clinic. Archived from the original on 8 October 2013.

- ^ S2CID 32258582.

- ^ Roehr B (21 September 2007). "Alcohol Rub, Antiseptic Wipes Inferior at Removing Clostridium difficile". Medscape. Archived from the original on 30 October 2013.

- PMID 29321078.

- PMID 21857653.

- ^ Laidman J (29 December 2011). "Flush With Germs: Lidless Toilets Spread C. difficile". Medscape. Archived from the original on 20 April 2016.

- ^ "Cleaning agents 'make bug strong'". BBC News Online. 3 April 2006. Archived from the original on 8 November 2006. Retrieved 17 November 2008.

- S2CID 25070569.

- PMID 23219675.

- ^ "Performance Feedback, Ultraviolet Cleaning Device, and Dedicated Housekeeping Team Significantly Improve Room Cleaning, Reduce Potential for Spread of Common, Dangerous Infection". Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. 15 January 2014. Retrieved 20 January 2014.

- ^ PMID 22184691.

- ^ PMID 29562266.

- ^ S2CID 54629762.

- PMID 23121552.

- ^ PMID 22610025.

- ^ S2CID 212638928.

- ^ S2CID 25356792.

- ^ "Merck Newsroom Home". Archived from the original on 3 November 2016. Retrieved 1 November 2016., FDA Approves Merck's ZINPLAVA (bezlotoxumab) to Reduce Recurrence of Clostridium difficile Infection (CDI) in Adult Patients Receiving Antibacterial Drug Treatment for CDI Who Are at High Risk of CDI Recurrence

- S2CID 24040330.

- PMID 18254055.

- PMID 28762696.

however, there are conflicting results for C. difficile infection.

- PMID 29183052.

- PMID 33437951.

- S2CID 34998497.

- ^ S2CID 1307726.

- S2CID 25879411.

- PMID 23990540.

- ^ "Ferring Receives U.S. FDA Approval for Rebyota (fecal microbiota, live-jslm) – A Novel First-in-Class Microbiota-Based Live Biotherapeutic". Ferring Pharmaceuticals USA. 1 December 2022. Retrieved 1 December 2022.

- ^ a b "FDA Approves First Orally Administered Fecal Microbiota Product for the Prevention of Recurrence of Clostridioides difficile Infection". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) (Press release). 26 April 2023. Retrieved 27 April 2023.

- ^ "Seres Therapeutics and Nestlé Health Science Announce FDA Approval of Vowst (fecal microbiota spores, live-brpk) for Prevention of Recurrence of C. difficile Infection in Adults Following Antibacterial Treatment for Recurrent CDI" (Press release). Seres Therapeutics. 26 April 2023. Retrieved 27 April 2023 – via Business Wire.

- PMID 37167952.

- S2CID 42729589.

- S2CID 27187695.

- PMID 18971494.

- PMID 24108611.

- ^ Rohlke, F., & Stollman, N. (2012). Fecal microbiota transplantation in relapsing Clostridium difficile infection. Therapeutic advances in gastroenterology, 5(6), 403–420. https://doi.org/10.1177/1756283X12453637

- ^ Cole, S. A., & Stahl, T. J. (2015). Persistent and Recurrent Clostridium difficile Colitis. Clinics in colon and rectal surgery, 28(2), 65–69. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0035-1547333

- ^ Dieterle, M. G., Rao, K., & Young, V. B. (2019). Novel therapies and preventative strategies for primary and recurrent Clostridium difficile infections. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1435(1), 110–138. https://doi.org/10.1111/nyas.13958

- ^ PMID 18971494.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-4511-8850-9. Archivedfrom the original on 8 September 2017.

- ^ "Antibiotic resistance threats in the United States, 2013" (PDF). US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2013. Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 November 2014. Retrieved 3 November 2014.

- ^ "Hospital Acquired Infections Are a Serious Risk - Consumer Reports". www.consumerreports.org. Archived from the original on 10 December 2016. Retrieved 18 December 2016.

- .

- ^ Prévot AR (1938). "Études de systématique bactérienne. IV. Critique de la conception actuelle du genre Clostridium". Annales de l'Institut Pasteur. 61 (1): 84.

- ISBN 978-0-387-68489-5.

- PMID 27370902.

- S2CID 2502330.

- ^ "Trust confirms 49 superbug deaths". BBC News Online. 1 October 2006. Archived from the original on 22 March 2007.

- ^ Hawkes N (11 January 2007). "Leaked memo reveals that targets to beat MRSA will not be met" (snippet). The Times. London. Retrieved 11 January 2007.(subscription required)

- ^ "C. difficile blamed for 9 death in hospital near Montreal". Canoe.ca. 27 October 2006. Archived from the original on 8 July 2012. Retrieved 11 January 2007.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ "12th person dies of C. difficile at Quebec hospital". CBC News. 18 November 2006. Archived from the original on 21 October 2007.

- ^ Hospitals struck by new killer bug Archived 20 May 2008 at the Wayback Machine An article by Manchester free newspaper 'Metro', 7 May 2008

- ^ "C. difficile outbreak linked to fatal strain" Archived 3 March 2007 at the Wayback Machine. CTV News. 28 February 2007.

- ^ "Superbug in hospitals linked to four deaths". Irish Independent. 10 October 2007.

- ^ ""Welcome to the Public Inquiry into the Outbreak of Clostridium difficile in Northern Trust Hospitals"". Archived from the original on 4 March 2016.

- ^ Healthcare watchdog finds significant failings in infection control at Maidstone and Tunbridge Wells NHS Trust (press release), United Kingdom: Healthcare Commission, 11 October 2007, archived from the original on 21 December 2007

- ^ Smith R, Rayner G, Adams S (11 October 2007). "Health Secretary intervenes in superbug row". Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 20 April 2008.

- ^ "Ärhäkkä suolistobakteeri on tappanut jo kymmenen potilasta – HS.fi – Kotimaa". Archived from the original on 15 December 2007.

- ^ "Possible C Diff link to Drogheda deaths". RTÉ News. 10 November 2009. Archived from the original on 23 October 2012.

- ^ 199 hit by the killer diarrhea at Herlev Hospital Archived 6 January 2016 at the Wayback Machine, BT 3 March 2010

- ^ (Herlev, Amager, Gentofte and Hvidovre)

- ^ Four hospitals affected by the dangerous bacterium Archived 5 July 2013 at the Wayback Machine, TV2 News 7 May 2010

- ^ "Deadly superbug reaches NZ". 3 News NZ. 30 October 2012. Archived from the original on 15 April 2014. Retrieved 29 October 2012.

- ^ "C. difficile linked to 26th death in Ontario". CBC News. 25 July 2011. Archived from the original on 24 July 2011. Retrieved 24 July 2011.

- ^ "10 punkter för att förhindra smittspridning i Region Skåne" [10 points to prevent the spread of infection in Region Skåne] (in Swedish). Archived from the original on 5 March 2015.

- ^ Liddell-Scott. "κλωστήρ". Greek-English Lexicon.

- ^ Cawley K. "Difficilis". Latin Dictionary and Grammar Aid. Retrieved 16 March 2013.

- ^ a b Stedman's Medical Dictionary, Wolters-Kluwer, retrieved 11 April 2019.

- PMID 31692324.

- ^ "Clostridium Difficile Vaccine Efficacy Trial (Clover)". clinicaltrials.gov. 21 February 2020. Retrieved 28 April 2020.

- ^ "Study of GlaxoSmithKline's (GSK) Clostridium Difficile Vaccine to Investigate the Safety and Ability to Provoke an Immune Response in the Body When Administered in Healthy Adults Aged 18-45 Years and 50-70 Years". clinicaltrials.gov. 13 April 2020. Retrieved 28 April 2020.

- ^ "op-line data from randomized, double-blind, placebo controlled Phase 2 clinical trial indicate statistically significant reduction in recurrences of CDAD". University of Massachusetts Worcester Campus. Archived from the original on 27 December 2010. Retrieved 16 August 2011.

- ^ CenterWatch. "Clostridium Difficile-Associated Diarrhea". Archived from the original on 29 September 2011. Retrieved 16 August 2011.

- ^ "MDX 066, MDX 1388 Medarex, University of Massachusetts Medical School clinical data (phase II)(diarrhea)". Highbeam. Archived from the original on 14 October 2012. Retrieved 16 August 2011.

- ^ PMID 20455684.

- PMID 26832756.

- S2CID 30463711.

- PMID 25942722.

- PMID 29310122.