Clostridium tetani

| Clostridium tetani | |

|---|---|

| |

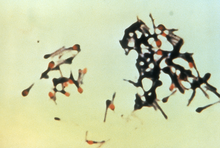

| Clostridium tetani forming spores | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Bacteria |

| Phylum: | Bacillota |

| Class: | Clostridia |

| Order: | Eubacteriales |

| Family: | Lachnospiraceae |

| Genus: | Clostridium |

| Species: | C. tetani

|

| Binomial name | |

| Clostridium tetani Flügge, 1881

| |

Clostridium tetani is a common soil bacterium and the causative agent of

Characteristics

Clostridium tetani is a

Upon exposure to various conditions, C. tetani can shed its flagellums and form a

Evolution

Clostridium tetani is classified within the genus Clostridium, a broad group of over 150 species of Gram-positive bacteria.

Role in disease

While C. tetani is frequently benign in the soil or in the intestinal tracts of animals, it can sometimes cause the severe disease

The gene encoding tetanospasmin is found on a plasmid carried by many strains of C. tetani; strains of bacteria lacking the plasmid are unable to produce toxin.[1][5] The function of tetanospasmin in bacterial physiology is unknown.[1]

Treatment and prevention

Clostridium tetani is susceptible to a number of

Damage from C. tetani infection is generally prevented by administration of a

Research

Clostridium tetani can be grown on various anaerobic

History

Clinical descriptions of tetanus associated with wounds are found at least as far back as the 4th century

References

- ^ ISBN 9781455700905.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-259-85980-9.

- ^ ISBN 9781118960608.

- ISBN 9780125950206.

- ^ a b c d Todar K (2005). "Pathogenic Clostridia, including Botulism and Tetanus". Todar's Online Textbook of Bacteriology. p. 3. Retrieved 24 June 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Hamborsky J, Kroger A, Wolfe C, eds. (2015). "Chapter 21: Tetanus". The Pink Book - Epidemiology and Prevention of Vaccine-Preventable Diseases (13 ed.). U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. pp. 341–352. Retrieved 24 June 2018.

- PMID 12552129.

- PMID 8609513.

- S2CID 30610331.