Coding region

The coding region of a gene, also known as the coding sequence (CDS), is the portion of a gene's DNA or RNA that codes for a protein.[1] Studying the length, composition, regulation, splicing, structures, and functions of coding regions compared to non-coding regions over different species and time periods can provide a significant amount of important information regarding gene organization and evolution of prokaryotes and eukaryotes.[2] This can further assist in mapping the human genome and developing gene therapy.[3]

Definition

Although this term is also sometimes used interchangeably with

There is often confusion between coding regions and exomes and there is a clear distinction between these terms. While the exome refers to all exons within a genome, the coding region refers to a singular section of the DNA or RNA which specifically codes for a certain kind of protein.

History

In 1978, Walter Gilbert published "Why Genes in Pieces" which first began to explore the idea that the gene is a mosaic—that each full nucleic acid strand is not coded continuously but is interrupted by "silent" non-coding regions. This was the first indication that there needed to be a distinction between the parts of the genome that code for protein, now called coding regions, and those that do not.[5]

Composition

The evidence suggests that there is a general interdependence between base composition patterns and coding region availability.[6] The coding region is thought to contain a higher GC-content than non-coding regions. There is further research that discovered that the longer the coding strand, the higher the GC-content. Short coding strands are comparatively still GC-poor, similar to the low GC-content of the base composition translational stop codons like TAG, TAA, and TGA.[7]

GC-rich areas are also where the ratio point mutation type is altered slightly: there are more transitions, which are changes from purine to purine or pyrimidine to pyrimidine, compared to transversions, which are changes from purine to pyrimidine or pyrimidine to purine. The transitions are less likely to change the encoded amino acid and remain a silent mutation (especially if they occur in the third nucleotide of a codon) which is usually beneficial to the organism during translation and protein formation.[8]

This indicates that essential coding regions (gene-rich) are higher in GC-content and more stable and resistant to mutation compared to accessory and non-essential regions (gene-poor).[9] However, it is still unclear whether this came about through neutral and random mutation or through a pattern of selection.[10] There is also debate on whether the methods used, such as gene windows, to ascertain the relationship between GC-content and coding region are accurate and unbiased.[11]

Structure and function

In

After transcription and maturation, the

Regulation

The coding region can be modified in order to regulate gene expression.

While the regulation of gene expression manages the abundance of RNA or protein made in a cell, the regulation of these mechanisms can be controlled by a regulatory sequence found before the open reading frame begins in a strand of DNA. The regulatory sequence will then determine the location and time that expression will occur for a protein coding region.[17]

Mutations

Mutations in the coding region can have very diverse effects on the phenotype of the organism. While some mutations in this region of DNA/RNA can result in advantageous changes, others can be harmful and sometimes even lethal to an organism's survival. In contrast, changes in the non-coding region may not always result in detectable changes in phenotype.

Mutation types

There are various forms of mutations that can occur in coding regions. One form is

Formation

Some forms of mutations are hereditary (germline mutations), or passed on from a parent to its offspring.[21] Such mutated coding regions are present in all cells within the organism. Other forms of mutations are acquired (somatic mutations) during an organism's lifetime, and may not be constant cell-to-cell.[21] These changes can be caused by mutagens, carcinogens, or other environmental agents (ex. UV). Acquired mutations can also be a result of copy-errors during DNA replication and are not passed down to offspring. Changes in the coding region can also be de novo (new); such changes are thought to occur shortly after fertilization, resulting in a mutation present in the offspring's DNA while being absent in both the sperm and egg cells.[21]

Prevention

There exist multiple transcription and translation mechanisms to prevent lethality due to deleterious mutations in the coding region. Such measures include

Constrained coding regions (CCRs)

While it is well known that the genome of one individual can have extensive differences when compared to the genome of another, recent research has found that some coding regions are highly constrained, or resistant to mutation, between individuals of the same species. This is similar to the concept of interspecies constraint in

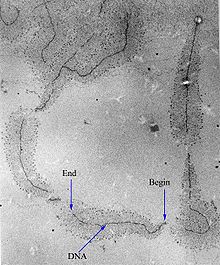

Coding sequence detection

While identification of

In both prokaryotes and eukaryotes, gene overlapping occurs relatively often in both DNA and RNA viruses as an evolutionary advantage to reduce genome size while retaining the ability to produce various proteins from the available coding regions.[27][28] For both DNA and RNA, pairwise alignments can detect overlapping coding regions, including short open reading frames in viruses, but would require a known coding strand to compare the potential overlapping coding strand with.[29] An alternative method using single genome sequences would not require multiple genome sequences to execute comparisons but would require at least 50 nucleotides overlapping in order to be sensitive.[30]

See also

- Coding strand The DNA strand that codes for a protein

- Exon The entire portion of the strand that is transcribed

- Mature mRNA The portion of the mRNA transcription product that is translated

- Gene structure The other elements that make up a gene

- Nested gene Entire coding sequence lies within the bounds of a larger external gene

- Non-coding DNA Parts of genomes that do not encode protein-coding genes

- Non-coding RNA Molecules that do not encode proteins, so have no CDS

References

- ^ a b Twyman, Richard (1 August 2003). "Gene Structure". The Wellcome Trust. Archived from the original on 28 March 2007. Retrieved 6 April 2003.

- S2CID 5978109.

- PMID 15217358.

- )

- S2CID 4216649.

- PMID 12915446.

- PMID 8703087.

- ^ "ROSALIND | Glossary | Gene coding region". rosalind.info. Retrieved 2019-10-31.

- PMID 12654999.

- PMID 28187704.

- PMID 15590696.

- ^ a b Overview of transcription. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.khanacademy.org/science/biology/gene-expression-central-dogma/transcription-of-dna-into-rna/a/overview-of-transcription .

- ^ Clancy, Suzanne (2008). "Translation: DNA to mRNA to Protein". Scitable: By Nature Education.

- ^ Plociam (2005-08-08), English: The structure of a mature eukaryotic mRNA. A fully processed mRNA includes the 5' cap, 5' UTR, coding region, 3' UTR, and poly(A) tail., retrieved 2019-11-19

- PMID 16500890.

- ^ "DNA alkylation Gene Ontology Term (GO:0006305)". www.informatics.jax.org. Retrieved 2019-10-30.

- .

- PMID 10397335.

- ^ Jonsta247 (2013-05-10), English: Example of silent mutation, retrieved 2019-11-19

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Yang, J. (2016, March 23). What are Genetic Mutation? Retrieved from https://www.singerinstruments.com/resource/what-are-genetic-mutation/ .

- ^ a b c What is a gene mutation and how do mutations occur? - Genetics Home Reference - NIH. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://ghr.nlm.nih.gov/primer/mutationsanddisorders/genemutation .

- ^ "DNA proofreading and repair (article)". Khan Academy. Retrieved 2023-05-22.

- ^ Peretó J. (2011) Wobble Hypothesis (Genetics). In: Gargaud M. et al. (eds) Encyclopedia of Astrobiology. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg

- ^ doi:10.1101/220814

- PMID 28261263.

- PMID 12819146.

- PMID 12047938.

- PMID 20610432.

- PMID 15347574.

- PMID 30099499.