Cofactor (biochemistry)

A cofactor is a non-protein chemical compound or metallic ion that is required for an enzyme's role as a catalyst (a catalyst is a substance that increases the rate of a chemical reaction). Cofactors can be considered "helper molecules" that assist in biochemical transformations. The rates at which these happen are characterized in an area of study called enzyme kinetics. Cofactors typically differ from ligands in that they often derive their function by remaining bound.

Cofactors can be classified into two types:

Coenzymes are further divided into two types. The first is called a "prosthetic group", which consists of a coenzyme that is tightly (or even covalently) and permanently bound to a protein.

Some enzymes or enzyme complexes require several cofactors. For example, the multienzyme complex pyruvate dehydrogenase[7] at the junction of glycolysis and the citric acid cycle requires five organic cofactors and one metal ion: loosely bound thiamine pyrophosphate (TPP), covalently bound lipoamide and flavin adenine dinucleotide (FAD), cosubstrates nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+) and coenzyme A (CoA), and a metal ion (Mg2+).[8]

Organic cofactors are often

Classification

Cofactors can be divided into two major groups: organic cofactors, such as flavin or heme; and inorganic cofactors, such as the metal ions Mg2+, Cu+, Mn2+ and iron–sulfur clusters.

Organic cofactors are sometimes further divided into coenzymes and prosthetic groups. The term coenzyme refers specifically to enzymes and, as such, to the functional properties of a protein. On the other hand, "prosthetic group" emphasizes the nature of the binding of a cofactor to a protein (tight or covalent) and, thus, refers to a structural property. Different sources give slightly different definitions of coenzymes, cofactors, and prosthetic groups. Some consider tightly bound organic molecules as prosthetic groups and not as coenzymes, while others define all non-protein organic molecules needed for enzyme activity as coenzymes, and classify those that are tightly bound as coenzyme prosthetic groups. These terms are often used loosely.

A 1980 letter in Trends in Biochemistry Sciences noted the confusion in the literature and the essentially arbitrary distinction made between prosthetic groups and coenzymes group and proposed the following scheme. Here, cofactors were defined as an additional substance apart from protein and

Inorganic cofactors

Metal ions

Other organisms require additional metals as enzyme cofactors, such as vanadium in the nitrogenase of the nitrogen-fixing bacteria of the genus Azotobacter,[18] tungsten in the aldehyde ferredoxin oxidoreductase of the thermophilic archaean Pyrococcus furiosus,[19] and even cadmium in the carbonic anhydrase from the marine diatom Thalassiosira weissflogii.[20][21]

In many cases, the cofactor includes both an inorganic and organic component. One diverse set of examples is the heme proteins, which consist of a porphyrin ring coordinated to iron.[22]

| Ion | Examples of enzymes containing this ion |

|---|---|

| Cupric | Cytochrome oxidase

|

| Ferrous or Ferric | Catalase Cytochrome (via Heme) Nitrogenase Hydrogenase |

| Magnesium | Glucose 6-phosphatase Hexokinase DNA polymerase |

| Manganese | Arginase |

| Molybdenum | Nitrate reductase Nitrogenase Xanthine oxidase |

| Nickel | Urease |

| Zinc | Alcohol dehydrogenase Carbonic anhydrase DNA polymerase |

Iron–sulfur clusters

Iron–sulfur clusters are complexes of iron and sulfur atoms held within proteins by cysteinyl residues. They play both structural and functional roles, including electron transfer, redox sensing, and as structural modules.[23]

Organic

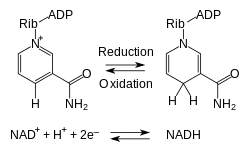

Organic cofactors are small organic molecules (typically a molecular mass less than 1000 Da) that can be either loosely or tightly bound to the enzyme and directly participate in the reaction.[5][24][25][26] In the latter case, when it is difficult to remove without denaturing the enzyme, it can be called a prosthetic group. It is important to emphasize that there is no sharp division between loosely and tightly bound cofactors.[5] Indeed, many such as NAD+ can be tightly bound in some enzymes, while it is loosely bound in others.[5] Another example is thiamine pyrophosphate (TPP), which is tightly bound in transketolase or pyruvate decarboxylase, while it is less tightly bound in pyruvate dehydrogenase.[27] Other coenzymes, flavin adenine dinucleotide (FAD), biotin, and lipoamide, for instance, are tightly bound.[28] Tightly bound cofactors are, in general, regenerated during the same reaction cycle, while loosely bound cofactors can be regenerated in a subsequent reaction catalyzed by a different enzyme. In the latter case, the cofactor can also be considered a substrate or cosubstrate.

Vitamins and derivatives

Non-vitamins

Cofactors as metabolic intermediates

Metabolism involves a vast array of chemical reactions, but most fall under a few basic types of reactions that involve the transfer of functional groups.[60] This common chemistry allows cells to use a small set of metabolic intermediates to carry chemical groups between different reactions.[61] These group-transfer intermediates are the loosely bound organic cofactors, often called coenzymes.

Each class of group-transfer reaction is carried out by a particular cofactor, which is the substrate for a set of enzymes that produce it, and a set of enzymes that consume it. An example of this are the

Therefore, these cofactors are continuously recycled as part of metabolism. As an example, the total quantity of ATP in the human body is about 0.1 mole. This ATP is constantly being broken down into ADP, and then converted back into ATP. Thus, at any given time, the total amount of ATP + ADP remains fairly constant. The energy used by human cells requires the hydrolysis of 100 to 150 moles of ATP daily, which is around 50 to 75 kg. In typical situations, humans use up their body weight of ATP over the course of the day.[62] This means that each ATP molecule is recycled 1000 to 1500 times daily.

Evolution

Organic cofactors, such as

Organic cofactors may have been present even earlier in the

A computational method, IPRO, recently predicted mutations that experimentally switched the cofactor specificity of Candida boidinii xylose reductase from NADPH to NADH.[69]

History

The first organic cofactor to be discovered was NAD+, which was identified by

The functions of these molecules were at first mysterious, but, in 1936, Otto Heinrich Warburg identified the function of NAD+ in hydride transfer.[74] This discovery was followed in the early 1940s by the work of Herman Kalckar, who established the link between the oxidation of sugars and the generation of ATP.[75] This confirmed the central role of ATP in energy transfer that had been proposed by Fritz Albert Lipmann in 1941.[76] Later, in 1949, Morris Friedkin and Albert L. Lehninger proved that NAD+ linked metabolic pathways such as the citric acid cycle and the synthesis of ATP.[77]

Protein-derived cofactors

In a number of enzymes, the moiety that acts as a cofactor is formed by post-translational modification of a part of the protein sequence. This often replaces the need for an external binding factor, such as a metal ion, for protein function. Potential modifications could be oxidation of aromatic residues, binding between residues, cleavage or ring-forming.[78] These alterations are distinct from other post-translation protein modifications, such as phosphorylation, methylation, or glycosylation in that the amino acids typically acquire new functions. This increases the functionality of the protein; unmodified amino acids are typically limited to acid-base reactions, and the alteration of resides can give the protein electrophilic sites or the ability to stabilize free radicals.[78] Examples of cofactor production include tryptophan tryptophylquinone (TTQ), derived from two tryptophan side chains,[79] and 4-methylidene-imidazole-5-one (MIO), derived from an Ala-Ser-Gly motif.[80] Characterization of protein-derived cofactors is conducted using X-ray crystallography and mass spectroscopy; structural data is necessary because sequencing does not readily identify the altered sites.

Non-enzymatic cofactors

The term is used in other areas of biology to refer more broadly to non-protein (or even protein) molecules that either activate, inhibit, or are required for the protein to function. For example,

See also

- Enzyme catalysis

- Inorganic chemistry

- Organometallic chemistry

- Bioorganometallic chemistry

- Cofactor engineering

References

- .

- ^ "coenzymes and cofactors". Archived from the original on 1999-08-26. Retrieved 2007-11-17.

- ^ "Enzyme Cofactors". Archived from the original on 2003-05-05. Retrieved 2007-11-17.

- ISBN 978-1429224161.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-12-492540-3.

- ^ de Bolster, M. W. G. (1997). GLOSSARY OF TERMS USED IN BIOINORGANIC CHEMISTRY (PDF). Pure & Appl. Chem.

- ISBN 978-0-8247-4062-7.

- ^ "Pyruvate Dehydrogenase Complex". Chemistry LibreTexts. 2013-10-02. Retrieved 2017-05-10.

- ^ S2CID 10848692.

- .

- ^ "Biochemistry: Enzymes: Classification and catalysis (Cofactors)". vle.du.ac.in. Retrieved 2018-02-07.[permanent dead link]

- PMID 3905079.

- S2CID 19417496.

- PMID 10736319.

- PMID 9133680.

- S2CID 15087548.

- PMID 8947828.

- PMID 3076437.

- S2CID 20868012.

- PMID 10781068.

- S2CID 52819760.

- PMID 21371326.

- S2CID 21961142.

- ISBN 978-0-85312-307-1.

- ISBN 978-1-57259-153-0.

- ISBN 978-0-495-39041-1.

- PMID 4968184.

- S2CID 7120148.

- PMID 17086936.

- PMID 3131330.

- S2CID 20415735.

- ^ PMID 17295611.

- PMID 15189147.

- S2CID 37393683.

- PMID 12769720.

- PMID 15893380.

- S2CID 218866247.

- PMID 10463148.

- PMID 17222174.

- ^ PMID 17275397.

- S2CID 12634062.

- ISBN 978-0-86542-793-8.

- S2CID 11214528.

- PMID 3086878.

- PMID 4367810.

- PMID 104960.

- S2CID 28013583. Archived from the originalon 16 December 2008.

- ISBN 978-0-943088-39-6.

- ISBN 978-1-4020-0178-9.

- PMID 6137189.

- PMID 15078160.

- PMID 9342247.

- PMID 12147719.

- PMID 16784786.

- PMID 351635.

- PMID 11396917.

- S2CID 3094647.

- PMID 10727395.

- PMID 2115763.

- PMID 378655.

- PMID 354490.

- ^ Di Carlo SE, Collins HL (2001). "Estimating ATP resynthesis during a marathon run: a method to introduce metabolism". Advan. Physiol. Edu. 25 (2): 70–1.

- S2CID 44873410.

- PMID 9889982.

- S2CID 39128865.

- S2CID 22282629.

- PMID 14687414.

- PMID 12458080.

- PMID 19693930.

- .

- ^ "Fermentation of sugars and fermentative enzymes: Nobel Lecture, May 23, 1930" (PDF). Nobel Foundation. Retrieved 2007-09-30.

- S2CID 20328411.

- .

- .

- S2CID 26999163.

- ISBN 9780674366701.

- PMID 18116985.

- ^ PMID 17439161.

- PMID 23746262.

- PMID 23633564.

- ^ Lodish, Harvey; Berk, Arnold; Zipursky, S. Lawrence; Matsudaira, Paul; Baltimore, David; Darnell, James (2000-01-01). "G Protein–Coupled Receptors and Their Effectors". Molecular Cell Biology (4th ed.).

- PMID 18701638.

Further reading

- Bugg T (1997). An introduction to enzyme and coenzyme chemistry. Oxford: Blackwell Science. ISBN 978-0-86542-793-8.

External links

- Cofactors lecture Archived 2016-10-05 at the Wayback Machine (Powerpoint file)

- Enzyme+cofactors at the U.S. National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)

- The CoFactor Database