Combined oral contraceptive pill

| Combined oral contraceptive pill | |

|---|---|

PMDD, endometriosis[citation needed] | |

| Risks | Possible small increase in some cancers.[4][5] Small reversible increase in DVTs; stroke,[6] cardiovascular disease[7] |

| Medical notes | |

| Affected by the antibiotic rifampicin,[8] the herb Hypericum (St. Johns Wort) and some anti-epileptics, also vomiting or diarrhea. Caution if history of migraines. | |

The combined oral contraceptive pill (COCP), often referred to as the birth control pill or colloquially as "the pill", is a type of

COCPs were first approved for contraceptive use in the United States in 1960, and remain a very popular form of birth control. They are used by more than 100 million women worldwide

Combined oral contraceptives are on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines.[21] The pill was a catalyst for the sexual revolution.[22]

Mechanism of action

Combined oral contraceptive pills were developed to prevent ovulation by suppressing the release of gonadotropins. Combined hormonal contraceptives, including COCPs, inhibit follicular development and prevent ovulation as a primary mechanism of action.[23][24][25][26]

Under normal circumstances, luteinizing hormone (LH) stimulates the theca cells of the ovarian follicle to produce androstenedione. The granulosa cells of the ovarian follicle then convert this androstenedione to estradiol. This conversion process is catalyzed by aromatase, an enzyme produced as a result of follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) stimulation.[27] In individuals using oral contraceptives, progestogen negative feedback decreases the pulse frequency of gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) release by the hypothalamus, which decreases the secretion of FSH and greatly decreases the secretion of LH by the anterior pituitary. Decreased levels of FSH inhibit follicular development, preventing an increase in estradiol levels. Progestogen negative feedback and the lack of estrogen positive feedback on LH secretion prevent a mid-cycle LH surge. Inhibition of follicular development and the absence of an LH surge prevent ovulation.[23][24][25]

Estrogen was originally included in oral contraceptives for better cycle control (to stabilize the endometrium and thereby reduce the incidence of breakthrough bleeding), but was also found to inhibit follicular development and help prevent ovulation. Estrogen negative feedback on the anterior pituitary greatly decreases the secretion of FSH, which inhibits follicular development and helps prevent ovulation.[23][24][25]

Another primary mechanism of action of all progestogen-containing contraceptives is inhibition of

The estrogen and progestogen in COCPs have other effects on the reproductive system, but these have not been shown to contribute to their contraceptive efficacy:[23]

- Slowing tubal motility and ova transport, which may interfere with fertilization.

- implantation.

- Endometrial edema, which may affect implantation.

Insufficient evidence exists on whether changes in the endometrium could actually prevent implantation. The primary mechanisms of action are so effective that the possibility of fertilization during COCP use is very small. Since pregnancy occurs despite endometrial changes when the primary mechanisms of action fail, endometrial changes are unlikely to play a significant role, if any, in the observed effectiveness of COCPs.[23]

Formulations

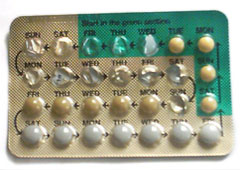

Oral contraceptives come in a variety of formulations, some containing both

COCPs have been somewhat inconsistently grouped into "generations" in the medical literature based on when they were introduced.[28][29]

- First generation COCPs are sometimes defined as those containing the progestins noretynodrel, norethisterone, norethisterone acetate, or etynodiol acetate;[28] and sometimes defined as all COCPs containing ≥ 50 µg ethinylestradiol.[29]

- Second generation COCPs are sometimes defined as those containing the progestins norgestrel or levonorgestrel;[28] and sometimes defined as those containing the progestins norethisterone, norethisterone acetate, etynodiol acetate, norgestrel, levonorgestrel, or norgestimate and < 50 µg ethinylestradiol.[29]

- Third generation COCPs are sometimes defined as those containing the progestins desogestrel or gestodene;[29] and sometimes defined as those containing desogestrel, gestodene, or norgestimate.[28]

- Fourth generation COCPs are sometimes defined as those containing the progestin drospirenone;[28] and sometimes defined as those containing drospirenone, dienogest, or nomegestrol acetate.[29]

Medical use

Contraceptive use

Combined oral contraceptive pills are a type of oral medication that were originally designed to be taken every day at the same time of day in order to prevent pregnancy.[30][31] There are many different formulations or brands, but the average pack is designed to be taken over a 28-day period (also known as a cycle). For the first 21 days of the cycle, users take a daily pill that contains two hormones, estrogen and progestogen. During the last 7 days of the cycle, users take daily placebo (biologically inactive) pills and these days are considered hormone-free days. Although these are hormone-free days, users are still protected from pregnancy during this time.

Some COCP packs only contain 21 pills and users are advised to take no pills for the last 7 days of the cycle.

Most monophasic COCPs can be used continuously such that patients can skip placebo days and continuously take hormone active pills from a COCP pack.[9] One of the most common reasons users do this is to avoid or diminish withdrawal bleeding. The majority of women on cyclic COCPs have regularly scheduled withdrawal bleeding, which is vaginal bleeding mimicking users' menstrual cycles with the exception of lighter menstrual bleeding compared to bleeding patterns prior to COCP commencement. As such, a study reported that out of 1003 women taking COCPs approximately 90% reported regularly scheduled withdrawal bleeds over a 90-day standard reference period.[9] Withdrawal bleeding usually occurs during the placebo, hormone-free days. Therefore, avoiding placebo days can diminish withdrawal bleeding among other placebo effects.

Effectiveness

If used exactly as instructed, the estimated risk of getting pregnant is 0.3% which means that about 3 in 1000 women on COCPs will become pregnant within one year.[33] However, typical use of COCPs by users often consists of timing errors, forgotten pills, or unwanted side effects. With typical use, the estimated risk of getting pregnant is about 9% which means that about 9 in 100 women on COCPs will become pregnant in one year.[34] The perfect use failure rate is based on a review of pregnancy rates in clinical trials, and the typical use failure rate is based on a weighted average of estimates from the 1995 and 2002 US National Surveys of Family Growth (NSFG), corrected for underreporting of abortions.[35][36]

Several factors account for typical use effectiveness being lower than perfect use effectiveness:

- Mistakes on part of those providing instructions on how to use the method

- Mistakes on part of the user

- Conscious user non-compliance with instructions

For instance, someone using COCPs might have received incorrect information by a health care provider about medication frequency, forgotten to take the pill one day or not gone to the pharmacy in time to renew her COCP prescription.

COCPs provide effective contraception from the very first pill if started within five days of the beginning of the menstrual cycle (within five days of the first day of menstruation). If started at any other time in the menstrual cycle, COCPs provide effective contraception only after 7 consecutive days of use of active pills, so a backup method of contraception (e.g. condoms) must be used in the interim.[37][38]

The effectiveness of COCPs appears to be similar whether the active pills are taken continuously or if they are taken cyclically.[39] Contraceptive efficacy, however, could be impaired by numerous means. Factors that may contribute to a decrease in effectiveness:[37]

- Missing more than one active pill in a packet,

- Delay in starting the next packet of active pills (i.e., extending the pill-free, inactive pill or placebo pill period beyond 7 days),

- ,

- Drug-drug interactions among COCPs and other medications of the user that decrease contraceptive estrogen and/or progestogen levels.[37]

In any of these instances, a backup contraceptive method should be used until hormone active pills have been consistently taken for 7 consecutive days or drug-drug interactions or underlying illnesses have been discontinued or resolved.[37] According to the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) guidelines, a pill is considered "late" if a user takes the pill after the user's normal medication time, but no longer than 24 hours after this normal time. If 24 hours or more have passed since the time the user was supposed to take the pill, then the pill is considered "missed."[33] CDC guidelines discuss potential next steps for users who missed their pill or took it late.[40]

Role of placebo pills

The role of the placebo pills is two-fold: to allow the user to continue the routine of taking a pill every day and to simulate the average menstrual cycle. By continuing to take a pill every day, users remain in the daily habit even during the week without hormones. Failure to take pills during the placebo week does not impact the effectiveness of the pill, provided that daily ingestion of active pills is resumed at the end of the week.[citation needed]

The placebo, or hormone-free, week in the 28-day pill package simulates an average menstrual cycle, though the hormonal events during a pill cycle are significantly different from those of a normal ovulatory menstrual cycle. Because the pill suppresses ovulation (to be discussed more in the Mechanism of action section), birth control users do not have true menstrual periods. Instead, it is the lack of hormones for a week that causes a withdrawal bleed.[31] The withdrawal bleeding that occurs during the break from active pills has been thought to be reassuring, a physical confirmation of not being pregnant.[41] The withdrawal bleeding is also predictable. Unexpected breakthrough bleeding can be a possible side effect of longer term active regimens.[42]

Since it is not uncommon for menstruating women to become anemic, some placebo pills may contain an iron supplement.[43][44] This replenishes iron stores that may become depleted during menstruation. As well, birth control pills, such as COCPs, are sometimes fortified with folic acid as it is recommended to take folic acid supplementation in the months prior to pregnancy to decrease the likelihood of neural tube defect in infants.[45][46]

No or less frequent placebos

If the pill formulation is monophasic, meaning each hormonal pill contains a fixed dose of hormones, it is possible to skip withdrawal bleeding and still remain protected against conception by skipping the placebo pills altogether and starting directly with the next packet. Attempting this with bi- or tri-phasic pill formulations carries an increased risk of

Starting in 2003, women have also been able to use a three-month version of the pill.

A version of the combined pill has also been packaged to eliminate placebo pills and withdrawal bleeds. Marketed as Anya or Lybrel, studies have shown that after seven months, 71% of users no longer had any breakthrough bleeding, the most common side effect of going longer periods of time without breaks from active pills.

While more research needs to be done to assess the long term safety of using COCP's continuously, studies have shown there may be no difference in short term adverse effects when comparing continuous use versus cyclic use of birth control pills.[39]

Non-contraceptive use

The hormones in the pill have also been used to treat other medical conditions, such as polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), endometriosis, adenomyosis, acne, hirsutism, amenorrhea, menstrual cramps, menstrual migraines, menorrhagia (excessive menstrual bleeding), menstruation-related or fibroid-related anemia and dysmenorrhea (painful menstruation).[34][48] Besides acne, no oral contraceptives have been approved by the US FDA for the previously mentioned uses despite extensive use for these conditions.[49]

PCOS

The cause of PCOS, or polycystic ovary syndrome, is multifactorial and not well-understood. Women with PCOS often have higher than normal levels of luteinizing hormone (LH) and androgens that impact the normal function of the ovaries.[50] While multiple small follicles develop in the ovary, none are able to grow in size enough to become the dominant follicle and trigger ovulation.[51] This leads to an imbalance of LH, follicle stimulating hormone, estrogen, and progesterone. Without ovulation, unopposed estrogen can lead to endometrial hyperplasia, or overgrowth of tissue in the uterus.[52] This endometrial overgrowth is more likely to become cancerous than normal endometrial tissue.[53] Thus, although the data varies, it is generally agreed upon by most gynecological societies that due to the unopposed estrogen, women with PCOS are at higher risk for endometrial cancer.[54]

To reduce the risk of endometrial cancer, it is often recommended that women with PCOS who do not desire pregnancy take hormonal contraceptives to prevent the effects of unopposed estrogen. Both COCPs and progestin-only methods are recommended.[citation needed] It is the progestin component of COCPs that protects the endometrium from hyperplasia, and thus reduces a woman with PCOS's endometrial cancer risk.[55] COCPs are preferred to progestin-only methods in women who also have uncontrolled acne, symptoms of hirsutism, and androgenic alopecia, because COCPs can help treat these symptoms.[31]

Acne and hirsutism

COCPs are sometimes prescribed to treat symptoms of androgenization, including acne and hirsutism.[56] The estrogen component of COCPs appears to suppress androgen production in the ovaries. Estrogen also leads to increased synthesis of sex hormone binding globulin, which causes a decrease in the levels of free testosterone.[57]

Ultimately, the drop in the level of free androgens leads to a decrease in the production of sebum, which is a major contributor to development of acne.[

Hirsutism is the growth of coarse, dark hair where women typically grow only fine hair or no hair at all.[61] This hair growth on the face, chest, and abdomen is also mediated by higher levels or action of androgens. Therefore, COCPs also work to treat these symptoms by lowering the levels of free circulating androgens.[62]

Endometriosis

For pelvic pain associated with endometriosis, COCPs are considered a first-line medical treatment, along with NSAIDs, GnRH agonists, and aromatase inhibitors.[63] COCPs work to suppress the growth of the extra-uterine endometrial tissue. This works to lessen its inflammatory effects.[31] COCPs, along with the other medical treatments listed above, do not eliminate the extra-uterine tissue growth, they just reduce the symptoms. Surgery is the only definitive treatment. Studies looking at rates of pelvic pain recurrence after surgery have shown that continuous use of COCPs is more effective at reducing the recurrence of pain than cyclic use.[64]

Adenomyosis

Similar to endometriosis, adenomyosis is often treated with COCPs to suppress the growth the endometrial tissue that has grown into the myometrium. Unlike endometriosis however, levonorgestrel containing IUDs are more effective at reducing pelvic pain in adenomyosis than COCPs.[31]

Menorrhagia

In the average menstrual cycle, a woman typically loses 35 to 40 milliliters of blood.[65] However, up to 20% of women experience much heavier bleeding, or menorrhagia.[66] This excess blood loss can lead to anemia, with symptoms of fatigue and weakness, as well as disruption in their normal life activities.[67] COCPs contain progestin, which causes the lining of the uterus to be thinner, resulting in lighter bleeding episodes for those with heavy menstrual bleeding.[68]

Amenorrhea

Although the pill is sometimes prescribed to induce menstruation on a regular schedule for women bothered by irregular menstrual cycles, it actually suppresses the normal menstrual cycle and then mimics a regular 28-day monthly cycle.

Women who are experiencing menstrual dysfunction due to

Contraindications

While combined oral contraceptives are generally considered to be a relatively safe medication, they are contraindicated for those with certain medical conditions. The

Hypercoagulability

Estrogen in high doses can increase risk of blood clots. All COCP users have a small increase in the risk of venous thromboembolism compared with non-users; this risk is greatest within the first year of COCP use.[71] Individuals with any pre-existing medical condition that also increases their risk for blood clots have a more significant increase in risk of thrombotic events with COCP use.[71] These conditions include but are not limited to high blood pressure, pre-existing cardiovascular disease (such as valvular heart disease or ischemic heart disease[72]), history of thromboembolism or pulmonary embolism, cerebrovascular accident, and a familial tendency to form blood clots (such as familial factor V Leiden).[73] There are conditions that, when associated with COCP use, increase risk of adverse effects other than thrombosis. For example, women with a history of migraine with aura have an increased risk of stroke when using COCPs, and women who smoke over age 35 and use COCPs are at higher risk of myocardial infarction.[70]

Pregnancy and postpartum

Women who are known to be pregnant should not take COCPs. Those in the postpartum period who are breastfeeding are also advised not to start COCPs until 4 weeks after birth due to increased risk of blood clots.[33] While studies have demonstrated conflicting results about the effects of COCPs on lactation duration and milk volume, there exist concerns about the transient risk of COCPs on breast milk production when breastfeeding is being established early postpartum.[74] Due to the stated risks and additional concerns on lactation, women who are breastfeeding are not advised to start COCPs until at least six weeks postpartum, while women who are not breastfeeding and have no other risks factors for blood clots may start COCPs after 21 days postpartum.[75][70]

Breast cancer

The World Health Organization (WHO) does not recommend the use of COCPs in women with breast cancer.[34][76] Since COCPs contain both estrogen and progestin, they are not recommended to be used in those with hormonally-sensitive cancers, including some types of breast cancer.[77][unreliable medical source?][78] Non-hormonal contraceptive methods, such as the Copper IUD or condoms,[79] should be the first-line contraceptive choice for these patients instead of COCPs.[80][unreliable medical source?]

Other

Women with known or suspected

Side effects

It is generally accepted that the health risks of oral contraceptives are lower than those from pregnancy and birth,[81] and "the health benefits of any method of contraception are far greater than any risks from the method".[82] Some organizations have argued that comparing a contraceptive method to no method (pregnancy) is not relevant—instead, the comparison of safety should be among available methods of contraception.[83]

Common

Different sources note different incidence of side effects. The most common side effect is

On the other hand, the pills can sometimes improve conditions such as dysmenorrhea, premenstrual syndrome, and acne,[87] reduce symptoms of endometriosis and polycystic ovary syndrome, and decrease the risk of anemia.[88] Use of oral contraceptives also reduces lifetime risk of ovarian and endometrial cancer.[89][90][91] Women have experienced amenorrhea, easy administration, and improvement in sexual function in some patients.[92]

Nausea, vomiting, headache, bloating, breast tenderness, swelling of the ankles/feet (fluid retention), or weight change may occur. Vaginal bleeding between periods (spotting) or missed/irregular periods may occur, especially during the first few months of use.[93]

Heart and blood vessels

Combined oral contraceptives increase the risk of

While lower doses of estrogen in COC pills may have a lower risk of stroke and myocardial infarction compared to higher estrogen dose pills (50 μg/day), users of low estrogen dose COC pills still have an increased risk compared to non-users.[95] These risks are greatest in women with additional risk factors, such as smoking (which increases risk substantially) and long-continued use of the pill, especially in women over 35 years of age.[96]

The overall absolute risk of venous thrombosis per 100,000 woman-years in current use of combined oral contraceptives is approximately 60, compared with 30 in non-users.[97] The risk of thromboembolism varies with different types of birth control pills; compared with combined oral contraceptives containing levonorgestrel (LNG), and with the same dose of estrogen and duration of use, the rate ratio of deep venous thrombosis for combined oral contraceptives with norethisterone is 0.98, with norgestimate 1.19, with desogestrel (DSG) 1.82, with gestodene 1.86, with drospirenone (DRSP) 1.64, and with cyproterone acetate 1.88.[97] In comparison, venous thromboembolism occurs in 100–200 per 100.000 pregnant women every year.[97]

One study showed more than a 600% increased risk of blood clots for women taking COCPs with drospirenone compared with non-users, compared with 360% higher for women taking birth control pills containing levonorgestrel.[98] The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) initiated studies evaluating the health of more than 800,000 women taking COCPs and found that the risk of VTE was 93% higher for women who had been taking drospirenone COCPs for 3 months or less and 290% higher for women taking drospirenone COCPs for 7–12 months, compared with women taking other types of oral contraceptives.[99]

Based on these studies, in 2012, the FDA updated the label for drospirenone COCPs to include a warning that contraceptives with drospirenone may have a higher risk of dangerous blood clots.[100]

A 2015 systematic review and meta-analysis found that combined birth control pills were associated with 7.6-fold higher risk of cerebral venous sinus thrombosis, a rare form of stroke in which blood clotting occurs in the cerebral venous sinuses.[101]

| Type | Route | Medications | Odds ratio (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

Menopausal hormone therapy |

Oral | Estradiol alone ≤1 mg/day >1 mg/day |

1.27 (1.16–1.39)* 1.22 (1.09–1.37)* 1.35 (1.18–1.55)* |

| Conjugated estrogens alone ≤0.625 mg/day >0.625 mg/day |

1.49 (1.39–1.60)* 1.40 (1.28–1.53)* 1.71 (1.51–1.93)* | ||

| Estradiol/medroxyprogesterone acetate | 1.44 (1.09–1.89)* | ||

| Estradiol/dydrogesterone ≤1 mg/day E2 >1 mg/day E2 |

1.18 (0.98–1.42) 1.12 (0.90–1.40) 1.34 (0.94–1.90) | ||

| Estradiol/norethisterone ≤1 mg/day E2 >1 mg/day E2 |

1.68 (1.57–1.80)* 1.38 (1.23–1.56)* 1.84 (1.69–2.00)* | ||

Estradiol/norgestrel or estradiol/drospirenone |

1.42 (1.00–2.03) | ||

| Conjugated estrogens/medroxyprogesterone acetate | 2.10 (1.92–2.31)* | ||

| Conjugated estrogens/norgestrel ≤0.625 mg/day CEEs >0.625 mg/day CEEs |

1.73 (1.57–1.91)* 1.53 (1.36–1.72)* 2.38 (1.99–2.85)* | ||

| Tibolone alone | 1.02 (0.90–1.15) | ||

| Raloxifene alone | 1.49 (1.24–1.79)* | ||

Transdermal |

Estradiol alone ≤50 μg/day >50 μg/day |

0.96 (0.88–1.04) 0.94 (0.85–1.03) 1.05 (0.88–1.24) | |

| Estradiol/progestogen | 0.88 (0.73–1.01) | ||

Vaginal |

Estradiol alone | 0.84 (0.73–0.97) | |

| Conjugated estrogens alone | 1.04 (0.76–1.43) | ||

Combined birth control |

Oral | Ethinylestradiol/norethisterone | 2.56 (2.15–3.06)* |

| Ethinylestradiol/levonorgestrel | 2.38 (2.18–2.59)* | ||

Ethinylestradiol/norgestimate |

2.53 (2.17–2.96)* | ||

| Ethinylestradiol/desogestrel | 4.28 (3.66–5.01)* | ||

| Ethinylestradiol/gestodene | 3.64 (3.00–4.43)* | ||

| Ethinylestradiol/drospirenone | 4.12 (3.43–4.96)* | ||

| Ethinylestradiol/cyproterone acetate | 4.27 (3.57–5.11)* | ||

| Notes: (1) Bioidentical progesterone was not included, but is known to be associated with no additional risk relative to estrogen alone. Footnotes: * = Statistically significant (p < 0.01). Sources: See template.

| |||

Cancer

Decreased risk of ovarian, endometrial, and colorectal cancers

Usage of combined oral concetraption decreased the risk of ovarian cancer, endometrial cancer,[37] and colorectal cancer.[4][87][102] Two large cohort studies published in 2010 both found a significant reduction in adjusted relative risk of ovarian and endometrial cancer mortality in ever-users of OCs compared with never-users.[2][103] The use of oral contraceptives (birth control pills) for five years or more decreases the risk of ovarian cancer in later life by 50%.[102][104] Combined oral contraceptive use reduces the risk of ovarian cancer by 40% and the risk of endometrial cancer by 50% compared with never users. The risk reduction increases with duration of use, with an 80% reduction in risk for both ovarian and endometrial cancer with use for more than 10 years. The risk reduction for both ovarian and endometrial cancer persists for at least 20 years.[37]

Increased risk of breast, cervical, and liver cancers

A report by a 2005

Weight

A 2016 systematic review found low quality evidence that studies of combination hormonal contraceptives showed no large difference in weight when compared with placebo or no intervention groups.[110] The evidence was not strong enough to be certain that contraceptive methods do not cause some weight change, but no major effect was found.[110] This review also found "that women did not stop using the pill or patch because of weight change."[110]

Sexual function and risk aversion

Sexual desire

Some researchers question a causal link between COCP use and decreased libido;[111] a 2007 study of 1700 women found COCP users experienced no change in sexual satisfaction.[112] A 2005 laboratory study of genital arousal tested fourteen women before and after they began taking COCPs. The study found that women experienced a significantly wider range of arousal responses after beginning pill use; decreases and increases in measures of arousal were equally common.[113][114]

In 2012, The Journal of Sexual Medicine published a review of research studying the effects of hormonal contraceptives on female sexual function that concluded that the sexual side effects of hormonal contraceptives are not well-studied and especially in regards to impacts on libido, with research establishing only mixed effects where only small percentages of women report experiencing an increase or decrease and majorities report being unaffected.[115] In 2013, The European Journal of Contraception & Reproductive Health Care published a review of 36 studies including 8,422 female subjects in total taking COCPs that found that 5,358 subjects (or 63.6 percent) reported no change in libido, 1,826 subjects (or 21.7 percent) reported an increase, and 1,238 subjects (or 14.7 percent) reported a decrease.[116] In 2019, Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews published a meta-analysis of 22 published and 4 unpublished studies (with 7,529 female subjects in total) that evaluated whether women expose themselves to greater health risks at different points in the menstrual cycle including by sexual activity with partners and found that subjects in the last third of the follicular phase and at ovulation (when levels of endogenous estradiol and luteinizing hormones are heightened) experienced increased sexual activity with partners as compared with the luteal phase and during menstruation.[117]

A 2006 study of 124 premenopausal women measured sex hormone-binding globulin (SHBG), including before and after discontinuation of the oral contraceptive pill. Women continuing use of oral contraceptives had SHBG levels four times higher than those who never used it, and levels remained elevated even in the group that had discontinued its use.[118][119] Theoretically, an increase in SHBG may be a physiologic response to increased hormone levels, but may decrease the free levels of other hormones, such as androgens, because of the unspecificity of its sex hormone binding. In 2020, The Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology published a cross-sectional study of 588 premenopausal female subjects aged 18 to 39 years from the Australian states of Queensland, New South Wales, and Victoria with regular menstrual cycles whose SHBG levels were measured by immunoassay that found that after controlling for age, body mass index, cycle stage, smoking, parity, partner status, and psychoactive medication, SHBG was inversely correlated with sexual desire.[120]

Sexual attractiveness and function

COCPs may increase natural vaginal lubrication,[121] while some women experience decreased lubrication.[121][122]

In 2004, the

In 2007, Evolution and Human Behavior published a study where 18 professional lap dancers recorded their menstrual cycles, work shifts, and tip earnings at gentlemen's clubs for 60 days that found by a mixed model analysis of 296 work shifts (or approximately 5,300 lap dances) that the 11 dancers with normal menstrual cycles earned US$335 per 5-hour shift during the late follicular phase and at ovulation, US$260 per shift during the luteal phase, and US$185 per shift during menstruation, while the 7 dancers using hormonal contraceptives showed no earnings peak during the late follicular phase and at ovulation.[124] In 2008, Evolution and Human Behavior published a study where the voices of 51 female students at the State University of New York at Albany were recorded with the women counting from 1 to 10 at four different points in their menstrual cycles were rated by blinded subjects who listened to the recordings to be more attractive at the points of the menstrual cycle with higher probabilities of conception, while the ratings of the voices of the women who were taking hormonal contraceptives showed no variation over the menstrual cycle in attractiveness.[125]

Risk-taking behaviour

In 1998, Evolution and Human Behavior published a study of 300 female undergraduate students at the State University of New York at Albany between the ages of 18 and 54 (with a mean age of 21.9 years) that surveyed the subjects engagement in 18 different behaviors over the 24 hours prior to filling out the study's questionnaire that varied in their risk of potential rape or sexual assault and the first day of their last menstruations, and found that subjects at ovulation showed statistically significant decreased engagement in behaviors that risked rape and sexual assault while subjects taking birth control pills showed no variation over their menstrual cycles in the same behaviors (suggesting a psychologically adaptive function of the hormonal fluctuations during the menstrual cycle in causing avoidance of behaviors that risk rape and sexual assault).[126][127] In 2003, Evolution and Human Behavior published a conceptual replication study of the 1998 survey that confirmed its findings.[128]

In 2006, a study presented at the annual conference of the Cognitive Science Society surveyed 176 female undergraduate students at Michigan State University (with a mean age of 19.9 years) in a decision-making experiment where the subjects chose between an option with a guaranteed outcome or an option involving risk and indicated the first day of their last menstruations, and found that the subjects risk aversion preferences varied over the menstrual cycle (with none of the subjects at ovulation preferring the risky option) and only subjects not taking hormonal contraceptives showed the menstrual cycle effect on risk aversion.[129] In the 2019 Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews meta-analysis, the research reviewed also evaluated whether the 7,529 female subjects across the 26 studies showed greater risk recognition and avoidance of potentially threatening people and dangerous situations at different phases of the menstrual cycle and found that the subjects displayed better risk accuracy recognition during the late follicular phase and at ovulation as compared to the luteal phase.[117]

Depression

Low levels of

Progestin-only contraceptives are known to worsen the condition of women who are already depressed.[133][134] However, current medical reference textbooks on contraception[37] and major organizations such as the American ACOG,[135] the WHO,[70] and the United Kingdom's RCOG[136] agree that current evidence indicates low-dose combined oral contraceptives are unlikely to increase the risk of depression, and unlikely to worsen the condition in women that are depressed.

Hypertension

Bradykinin lowers blood pressure by causing blood vessel dilation. Certain enzymes are capable of breaking down bradykinin (Angiotensin Converting Enzyme, Aminopeptidase P). Progesterone can increase the levels of Aminopeptidase P (AP-P), thereby increasing the breakdown of bradykinin, which increases the risk of developing hypertension.[137]

Other effects

Other side effects associated with low-dose COCPs are

Excess estrogen, such as from birth control pills, appears to increase cholesterol levels in bile and decrease gallbladder movement, which can lead to

Combined oral contraception decreases total

Drug interactions

Some

The traditional medicinal herb

History

By the 1930s, scientists had isolated and determined the structure of the

but obtaining these hormones, which were produced from animal extracts, from EuropeanIn 1939,

Midway through the 20th century, the stage was set for the development of a

Progesterone to prevent ovulation

Progesterone, given by injections, was first shown to inhibit ovulation in animals in 1937 by Makepeace and colleagues.[167]

In 1951, reproductive

In March 1952, Sanger wrote a brief note mentioning Pincus' research to her longtime friend and supporter,

Pincus and McCormick enlisted

In 1953, at Pincus' suggestion, Rock induced a three-month anovulatory "pseudopregnancy" state in twenty-seven of his infertility patients with an oral 300 mg/day progesterone-only regimen for 20 days from

Progesterone was abandoned as an oral ovulation inhibitor following these clinical studies due to the high and expensive doses required, incomplete inhibition of ovulation, and the frequent incidence of breakthrough bleeding.[167][179] Instead, researchers would turn to much more potent synthetic progestogens for use in oral contraception in the future.[167][179]

Progestins to prevent ovulation

In October 1951, Chemist Luis Miramontes, working under the supervision of Carl Djerassi, and the direction of George Rosenkranz at Syntex in Mexico City, synthesized the first oral contraceptive, which was based on highly active progestin norethisterone. Frank B. Colton at Searle in Skokie, Illinois synthesized the orally highly active progestins noretynodrel (an isomer of norethisterone) in 1952 and norethandrolone in 1953.[162]

Pincus asked his contacts at pharmaceutical companies to send him chemical compounds with progestogenic activity. Chang screened nearly 200 chemical compounds in animals and found the three most promising were Syntex's norethisterone and Searle's noretynodrel and norethandrolone.[180]

In December 1954, Rock began the first studies of the ovulation-suppressing potential of 5–50 mg doses of the three oral progestins for three months (for 21 days per cycle—days 5–25 followed by pill-free days to produce withdrawal bleeding) in fifty of his patients with infertility in Brookline, Massachusetts. Norethisterone or noretynodrel 5 mg doses and all doses of norethandrolone suppressed ovulation but caused breakthrough bleeding, but 10 mg and higher doses of norethisterone or noretynodrel suppressed ovulation without breakthrough bleeding and led to a 14% pregnancy rate in the following five months. Pincus and Rock selected Searle's noretynodrel for the first contraceptive trials in women, citing its total lack of androgenicity versus Syntex's norethisterone very slight androgenicity in animal tests.[181][182]

Combined oral contraceptive

Noretynodrel (and norethisterone) were subsequently discovered to be contaminated with a small percentage of the estrogen

The first

While these large-scale trials contributed to the initial understanding of the pill formulation's clinical effects, the ethical implications of the trials generated significant controversy. Of note is the apparent lack of both autonomy and informed consent among participants in the Puerto Rican cohort prior to the trials. Many of these participants hailed from impoverished, working-class backgrounds.[10]

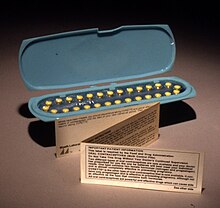

Public availability

United States

In June 1957, the

Although FDA-approved for contraceptive use, Searle never marketed Enovid 10 mg as a contraceptive. Eight months later, in February 1961, the FDA approved Enovid 5 mg for contraceptive use. In July 1961, Searle finally began marketing Enovid 5 mg (5 mg noretynodrel and 75 µg mestranol) to physicians as a contraceptive.[189][191]

Although the FDA approved the first oral contraceptive in 1960, contraceptives were not available to married women in all states until Griswold v. Connecticut in 1965, and were not available to unmarried women in all states until Eisenstadt v. Baird in 1972.[166][191]

The first published case report of a

Beginning in 2015, certain states passed legislation allowing pharmacists to prescribe oral contraceptives. Such legislation was considered to address physician shortages and decrease barriers to birth control for women.

Australia

The first oral contraceptive introduced outside the United States was Schering's Anovlar (norethisterone acetate 4 mg + ethinylestradiol 50 µg) in January 1961, in Australia.[202]

Germany

The first oral contraceptive introduced in Europe was Schering's

United Kingdom

Before the mid-1960s, the United Kingdom did not require pre-marketing approval of drugs. The British Family Planning Association (FPA) through its clinics was then the primary provider of family planning services in the UK and provided only contraceptives that were on its Approved List of Contraceptives (established in 1934). In 1957, Searle began marketing Enavid (Enovid 10 mg in the US) for menstrual disorders. Also in 1957, the FPA established a Council for the Investigation of Fertility Control (CIFC) to test and monitor oral contraceptives which began animal testing of oral contraceptives and in 1960 and 1961 began three large clinical trials in Birmingham, Slough, and London.[186][205]

In March 1960, the Birmingham FPA began trials of noretynodrel 2.5 mg + mestranol 50 µg, but a high pregnancy rate initially occurred when the pills accidentally contained only 36 µg of mestranol—the trials were continued with noretynodrel 5 mg + mestranol 75 µg (Conovid in the UK, Enovid 5 mg in the US).[206] In August 1960, the Slough FPA began trials of noretynodrel 2.5 mg + mestranol 100 µg (Conovid-E in the UK, Enovid-E in the US).[207] In May 1961, the London FPA began trials of Schering's Anovlar.[208]

In October 1961, at the recommendation of the Medical Advisory Council of its CIFC, the FPA added Searle's Conovid to its Approved List of Contraceptives.[209] In December 1961,

France

In December 1967, the Neuwirth Law legalized contraception in France, including the pill.[212] The pill is the most popular form of contraception in France, especially among young women. It accounts for 60% of the birth control used in France. The abortion rate has remained stable since the introduction of the pill.[213]

Japan

In Japan, lobbying from the Japan Medical Association prevented the pill from being approved for general use for nearly 40 years. The higher dose "second generation" pill was approved for use in cases of gynecological problems, but not for birth control. Two main objections raised by the association were safety concerns over long-term use of the pill, and concerns that pill use would lead to decreased use of condoms and thereby potentially increase sexually transmitted infection (STI) rates.[214]

However, when the Ministry of Health and Welfare approved

Society and culture

The pill was approved by the FDA in the early 1960s; its use spread rapidly in the late part of that decade, generating an enormous social impact. Time magazine placed the pill on its cover in April 1967.[219][220] In the first place, it was more effective than most previous reversible methods of birth control, giving women unprecedented control over their fertility.[221] Its use was separate from intercourse, requiring no special preparations at the time of sexual activity that might interfere with spontaneity or sensation, and the choice to take the pill was a private one. This combination of factors served to make the pill immensely popular within a few years of its introduction.[163][191]

Claudia Goldin, among others, argue that this new contraceptive technology was a key player in forming women's modern economic role, in that it prolonged the age at which women first married allowing them to invest in education and other forms of human capital as well as generally become more career-oriented. Soon after the birth control pill was legalized, there was a sharp increase in college attendance and graduation rates for women.[222] From an economic point of view, the birth control pill reduced the cost of staying in school. The ability to control fertility without sacrificing sexual relationships allowed women to make long term educational and career plans.[223]

Because the pill was so effective, and soon so widespread, it also heightened the debate about the moral and health consequences of

The United States Senate began hearings on the pill in 1970 and where different viewpoints were heard from medical professionals. Dr. Michael Newton, President of the College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists said:

The evidence is not yet clear that these still do in fact cause cancer or related to it. The FDA Advisory Committee made comments about this, that if there wasn't enough evidence to indicate whether or not these pills were related to the development of cancer, and I think that's still thin; you have to be cautious about them, but I don't think there is clear evidence, either one way or the other, that they do or don't cause cancer.[226]

Another physician, Dr. Roy Hertz of the Population Council, said that anyone who takes this should know of "our knowledge and ignorance in these matters" and that all women should be made aware of this so they can decide to take the pill or not.[226]

The

Result on popular culture

The introduction of the birth control pill in 1960 allowed more women to find employment opportunities and further their education. As a result of women getting more jobs and an education, their husbands had to start taking over household tasks like cooking.[227] Wanting to stop the change that was occurring in terms of gender norms in an American household, many films, television shows, and other popular culture items portrayed what an ideal American family should be. Below are listed some examples:

Poem

- The Pill Versus the Springhill Mine Disaster is the title poem of a 1968 collection by Richard Brautigan.[228]

Music

- Singer Loretta Lynn commented on how women no longer had to choose between a relationship and a career in her 1974 album with a song entitled "The Pill", which told the story of a married woman's use of the drug to liberate herself from her traditional role as wife and mother.[229]

Environmental impact

A woman using COCPs excretes in her urine and feces natural estrogens, estrone (E1) and estradiol (E2), and synthetic estrogen ethinylestradiol (EE2).[230] These hormones can pass through

A review of activated sludge plant performance found estrogen removal rates varied considerably but averaged 78% for estrone, 91% for estradiol, and 76% for ethinylestradiol (estriol effluent concentrations are between those of estrone and estradiol, but estriol is a much less potent endocrine disruptor to fish).[234]

Several studies have suggested that reducing human population growth through increased access to

See also

- Estradiol-containing oral contraceptive

- Hormone replacement therapy (HRT)

- List of estrogens available in the United States

- List of progestogens available in the United States

- Progestogen-only injectable contraceptive

References

- ^ OCLC 781956734. Table 26–1 = Table 3–2 Percentage of women experiencing an unintended pregnancy during the first year of typical use and the first year of perfect use of contraception, and the percentage continuing use at the end of the first year. United States. Archived 15 February 2017 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ PMID 20223876.

- ^ "Oral Contraceptives and Cancer Risk". National Cancer Institute. 22 February 2018. Archived from the original on 27 May 2020. Retrieved 10 May 2020.

- ^ a b c IARC working group (2007). "Combined Estrogen-Progestogen Contraceptives" (PDF). IARC Monographs on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans. 91. Archived (PDF) from the original on 3 August 2016. Retrieved 14 September 2010.

- S2CID 36136756.

- PMID 11988591.

- PMID 15814774.

- ^ "Birth Control Pills - Birth Control Pill - The Pill". Archived from the original on 5 August 2011. Retrieved 3 April 2009.

- ^ S2CID 245557522.

- ^ from the original on 8 November 2022. Retrieved 14 September 2022.

- ^ "Birth Control Pill (for Teens) - Nemours KidsHealth". kidshealth.org. Archived from the original on 21 September 2022. Retrieved 21 September 2022.

- OCLC 1135665739.

- PMID 23384741.

- ^ "Products - Data Briefs - Number 327 - December 2018". U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 11 July 2022. Archived from the original on 13 September 2022. Retrieved 14 September 2022.

- S2CID 6433771.

- ^ "Current Contraceptive Status Among Women Aged 15–49: United States, 2015–2017". U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 7 June 2019. Archived from the original on 13 September 2022. Retrieved 2 August 2019.

- ISBN 978-92-1-151418-6. Archived(PDF) from the original on 26 April 2018. Retrieved 28 June 2017. women aged 15–49 married or in consensual union

- ^ Delvin D (15 June 2016). "Contraception – the contraceptive pill: How many women take it in the UK?". Archived from the original on 4 January 2011. Retrieved 25 December 2010.

- ISBN 978-1-85774-638-9. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 January 2007. British women aged 16–49: 24% use the pill as of 2016[update](17% use Combined pill, 5% use Minipill, 2% don't know type)

- PMID 26872717.

- hdl:10665/371090. WHO/MHP/HPS/EML/2023.02.

- ^ Harris G (3 May 2010). "The Pill Started More Than One Revolution". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 27 September 2015. Retrieved 21 September 2015.

- ^ OCLC 781956734. pp. 257–258:

Mechanism of action

COCs prevent fertilization and, therefore, qualify as contraceptives. There is no significant evidence that they work after fertilization. The progestins in all COCs provide most of the contraceptive effect by suppressing ovulation and thickening cervical mucus, although the estrogens also make a small contribution to ovulation suppression. Cycle control is enhanced by the estrogen.

Because COCs so effectively suppress ovulation and block ascent of sperm into the upper genital tract, the potential impact on endometrial receptivity to implantation is almost academic. When the two primary mechanisms fail, the fact that pregnancy occurs despite the endometrial changes demonstrates that those endometrial changes do not significantly contribute to the pill's mechanism of action. - ^ ISBN 978-1-60831-610-6.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-07-162442-8.

- ISBN 978-1-4160-5583-9.

- from the original on 15 July 2023, retrieved 15 September 2022

- ^ OCLC 781956734.

Ten different progestins have been used in the COCs that have been sold in the United States. Several different classification systems for the progestins exist, but the one most commonly used system recapitulates the history of the pill in the United States by categorizing the progestins into the so-called "generations of progestins." The first three generations of progestins are derived from 19-nortestosterone. The fourth generation is drospirenone. Newer progestins are hybrids.

First-generation progestins. First-generation progestins include noretynodrel, norethisterone, norethisterone acetate, and etynodiol diacetate… These compounds have the lowest potency and relatively short half-lives. The short half-life did not matter in the early, high-dose pills but as doses of progestin were decreased in the more modern pills, problems with unscheduled spotting and bleeding became more common.

Second-generation progestins. To solve the problem of unscheduled bleeding and spotting, the second generation progestins (norgestrol and levonorgestrel) were designed to be significantly more potent and to have longer half-lives than norethisterone-related progestins ... The second-generation progestins have been associated with more androgen-related side-effects such as adverse effect on lipids, oily skin, acne, and facial hair growth.

Third-generation progestins. Third-generation progestins (desogestrel, norgestimate and elsewhere, gestodene) were introduced to maintain the potent progestational activity of second-generation progestins, but to reduce androgeneic side effects. Reduction in androgen impacts allows a fuller expression of the pill's estrogen impacts. This has some clinical benefits… On the other hand, concern arose that the increased expression of estrogen might increase the risk of venous thromboembolism (VTE). This concern introduced a pill scare in Europe until international studies were completed and correctly interpreted.

Fourth-generation progestins. Drospirenone is an analogue of spironolactone, a potassium-sparing diuretic used to treat hypertension. Drospirenone possesses anti-mineralocorticoid and anti-androgenic properties. These properties have led to new contraceptive applications, such as treatment of premenstrual dysphoric disorder and acne… In the wake of concerns around possible increased VTE risk with less androgenic third-generation formulations, those issues were anticipated with drospirenone. They were clearly answered by large international studies.

Next-generation progestins. Progestins have been developed with properties that are shared with different generations of progestins. They have more profound, diverse, and discrete effects on the endometrium than prior progestins. This class would include dienogest (United States) and nomegestrol (Europe). - ^ ISBN 978-1-60831-610-6.

- ^ a b "How to Use Birth Control Pills". Planned Parenthood. Archived from the original on 6 December 2017. Retrieved 29 November 2017.

- ^ OCLC 800907400.

- ^ "Birth Control Pills All Guides". October 2014. Archived from the original on 31 May 2023. Retrieved 20 October 2018.

- ^ OCLC 985676200.

- ^ (PDF) from the original on 16 October 2020. Retrieved 11 February 2024.

- PMID 19223239.

- PMID 21477680.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-7817-6488-9.

- ^ FFPRHC (2007). "Clinical Guidance: First Prescription of Combined Oral Contraception" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 July 2007. Retrieved 26 June 2007.

- ^ PMID 25072731.

- PMID 27467319.

- ^ Gladwell M (10 March 2000). "John Rock's Error". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on 11 May 2013. Retrieved 4 February 2009.

- ^ Mayo Clinic staff. "Birth control pill FAQ: Benefits, risks and choices". Mayo Clinic. Archived from the original on 26 December 2012. Retrieved 1 February 2013.

- ^ "US Patent:Oral contraceptive:Patent 6451778 Issued on September 17, 2002 Estimated Expiration Date: July 2, 2017". PatentStorm LLC. Archived from the original on 13 June 2011. Retrieved 19 November 2010.

- PMID 11683548.

- PMID 28097361.

- PMID 22570577.

- ^ "FDA Approves Seasonal Oral Contraceptive". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 25 September 2003. Archived from the original on 7 October 2006. Retrieved 9 November 2006.

- ^ CYWH Staff (18 October 2011). "Medical Uses of the Birth Control Pill". Archived from the original on 5 February 2013. Retrieved 1 February 2013.

- ^ "Information for Consumers (Drugs) - Find Information about a Drug". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Archived from the original on 14 November 2017. Retrieved 13 December 2017.

- ^ "Patient education: Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) (Beyond the Basics)". UpToDate. Archived from the original on 15 September 2022. Retrieved 15 September 2022.

- S2CID 10185317.

- ^ "Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS)". American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Archived from the original on 15 September 2022. Retrieved 15 September 2022.

- ^ Barakat RR, Park RC, Grigsby PW, et al. Corpus: Epithelial Tumors. In: Principles and Practice of Gynecologic Oncology, 2nd, Hoskins WH, Perez CA, Young RC (Eds), Lippincott-Raven Publishers, Philadelphia 1997. p.859

- S2CID 27453081.

- ^ "Can birth control pills cure PCOS". American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Archived from the original on 20 September 2022. Retrieved 18 September 2022.

- PMID 16371290.

- ^ "Hormonal Contraceptives and Acne: A Retrospective Analysis of 2147 Patients". JDDonline - Journal of Drugs in Dermatology. Archived from the original on 19 May 2022. Retrieved 15 September 2022.

- ^ Chang L. "Birth Control of Acne". WebMD, LLC. Archived from the original on 26 January 2013. Retrieved 1 February 2013.

- ^ "DailyMed - ORTHO TRI CYCLEN- norgestimate and ethinyl estradiol ORTHO CYCLEN- norgestimate and ethinyl estradiol". dailymed.nlm.nih.gov. Archived from the original on 14 December 2017. Retrieved 13 December 2017.

- ^ "Beyaz Package Insert" (PDF). U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Archived (PDF) from the original on 15 April 2023. Retrieved 6 August 2019.

- ^ "Patient education: Hirsutism (excess hair growth in females) (Beyond the Basics)". UpToDate. Archived from the original on 20 September 2022. Retrieved 18 September 2022.

- ^ "Hirsutism: What It Is, In Women, Causes, PCOS & Treatment". Cleveland Clinic. Archived from the original on 19 September 2022. Retrieved 18 September 2022.

- ^ "ACOG Endometriosis FAQ". Archived from the original on 1 February 2020. Retrieved 3 March 2019.

- S2CID 23340983.

- ^ "Heavy Menstrual Bleeding". American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Archived from the original on 20 September 2022. Retrieved 18 September 2022.

- from the original on 6 October 2022. Retrieved 15 September 2022.

- ^ "Patient education: Heavy or prolonged menstrual bleeding (menorrhagia) (Beyond the Basics)". UpToDate. Archived from the original on 15 September 2022. Retrieved 15 September 2022.

- ^ "Noncontraceptive Benefits of Birth Control Pills". American Society for Reproductive Medicine (ASRM). Archived from the original on 13 September 2022. Retrieved 15 September 2022.

- ^ ABIM Foundation, American Medical Society for Sports Medicine, archivedfrom the original on 29 July 2014, retrieved 29 July 2014

- ^ from the original on 11 February 2024. Retrieved 11 February 2024.

- ^ PMID 28413042.

- ^ from the original on 3 May 2019. Retrieved 5 August 2019.

- ^ a b "Can Any Woman Take Birth Control Pills?". WebMD. Archived from the original on 3 May 2016. Retrieved 8 May 2016.

- PMID 25793657.

- ^ "Classifications for Combined Hormonal Contraceptives". U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 9 April 2020. Archived from the original on 27 November 2020. Retrieved 7 December 2020.

- (PDF) from the original on 9 June 2023. Retrieved 11 February 2024.

- ^ "Is There a Link Between Birth Control Pills and Higher Breast Cancer Risk?". www.breastcancer.org. Archived from the original on 20 September 2022. Retrieved 18 September 2022.

- ^ Pernambuco-Holsten C (25 September 2018). "Birth Control and Cancer Risk: 6 Things You Should Know". Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center. Archived from the original on 20 September 2022. Retrieved 18 September 2022.

- ^ "What are the best birth control options that aren't hormonal?". Planned Parenthood. Archived from the original on 20 September 2022. Retrieved 18 September 2022.

- ^ "Do Hormonal Contraceptives Increase Breast Cancer Risk?". www.breastcancer.org. Archived from the original on 20 September 2022. Retrieved 18 September 2022.

- ISBN 978-0-534-65176-3.[page needed]

- WHO. 2005. Archivedfrom the original on 7 January 2007. Retrieved 14 September 2022.

- ^ Holck S. "Contraceptive Safety". Special Challenges in Third World Women's Health. 1989 Annual Meeting of the American Public Health Association. Archived from the original on 8 November 2017. Retrieved 7 October 2006.

- S2CID 11876371.

- PMID 11535214.

- PMID 7822673.

- ^ S2CID 73326364.

- ISBN 978-0-87893-617-5.[page needed]

- PMID 18061864.

- PMID 16050564.

- S2CID 196536513.

- PMID 22018133.

- ^ "Apri oral : Uses, Side Effects, Interactions, Pictures, Warnings & Dosing". Archived from the original on 13 December 2016. Retrieved 2 December 2016.

- S2CID 41309800.

- PMID 26310586.

- ISBN 978-0-7020-3471-8.

- ^ PMID 23825156.

- S2CID 2691199.

- S2CID 42721801.

- ^ "Highlights of Prescribing Information for Yasmin" (PDF). U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Archived (PDF) from the original on 25 April 2012. Retrieved 11 November 2012.

- PMID 25699010.

- ^ PMID 17302189.

- PMID 20705149.

- S2CID 26048792.

- PMID 20543200.

- PMID 24014598.

- S2CID 206616972.

- S2CID 33708638.

- ^ S2CID 4498610.

- ^ PMID 27567593.

- ISBN 978-0-7216-0376-6.[page needed]

- PMID 17403440.

- S2CID 10402534.

- PMID 24792147.

- PMID 22788250.

- S2CID 34748865.

- ^ from the original on 6 May 2023. Retrieved 27 April 2023.

- PMID 16409223.

Description of the study results in Medical News Today: "Birth Control Pill Could Cause Long-Term Problems With Testosterone, New Research Indicates". 4 January 2006. Archived from the original on 24 April 2011. Retrieved 9 April 2011. - PMID 16409223.

- S2CID 225473332.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-9664902-5-1.

- ISBN 978-0-7817-6488-9.

- PMID 15503991.

- (PDF) from the original on 13 June 2023. Retrieved 16 May 2023.

- .

- .

- ISBN 978-0-465-09776-0.

- .

- from the original on 27 April 2023. Retrieved 27 April 2023.

- S2CID 8836005.

- ^ PMID 27680324.

- ^ PMID 29566064.

- ^ Burnett-Watson K (October 2005). "Is The Pill Playing Havoc With Your Mental Health?". Archived from the original on 20 March 2007. Retrieved 20 March 2007., which cites:

- Kulkarni J, Liew J, Garland KA (November 2005). "Depression associated with combined oral contraceptives--a pilot study". Australian Family Physician. 34 (11): 990. PMID 16299641.

- Kulkarni J, Liew J, Garland KA (November 2005). "Depression associated with combined oral contraceptives--a pilot study". Australian Family Physician. 34 (11): 990.

- PMID 17629629.

- PMID 16738183.

- ^ FFPRHC (2006). "The UK Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use (2005/2006)" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 June 2007. Retrieved 31 March 2007.

- S2CID 206729914.

- ^ "Gallstones". NDDIC. July 2007. Archived from the original on 11 August 2010. Retrieved 13 August 2010.

- ^ Raloff J (23 April 2009). "Birth control pills can limit muscle-training gains". Science News. Archived from the original on 11 June 2012. Retrieved 22 October 2018.

- ^ "Love woes can be blamed on contraceptive pill: research – ABC News (Australian Broadcasting Corporation)". ABC News. Abc.net.au. 14 August 2008. Archived from the original on 22 July 2010. Retrieved 20 March 2010.

- PMID 28002464.

- PMID 18700206.

- PMID 20833638.

- PMID 24082040.

- PMID 21752879.

- ^ The effects of broad-spectrum antibiotics on Combined contraceptive pills is not found on systematic interaction metanalysis (Archer, 2002), although "individual patients do show large decreases in the plasma concentrations of ethinylestradiol when they take certain other antibiotics" (Dickinson, 2001). "experts on this topic still recommend informing oral contraceptive users of the potential for a rare interaction" (DeRossi, 2002) and this remains current (2006) UK Family Planning Association advice Archived 8 February 2007 at the Wayback Machine.

- PMID 12063491.

- S2CID 41354899.

- PMID 12436822.

- PMID 27444983.

- ISBN 978-0-300-08943-1. Archivedfrom the original on 11 January 2023. Retrieved 27 September 2020.

- ^ Gelijns A (1991). Innovation in Clinical Practice: The Dynamics of Medical Technology Development. National Academies. pp. 167–. NAP:13513. Archived from the original on 13 January 2023. Retrieved 27 September 2020.

- ISBN 978-1-4832-7738-7.

- ISBN 978-0-8147-8301-6.

- ISBN 978-3-527-29874-7.

- ISBN 978-81-250-1622-9.

- ISBN 978-3-642-96158-8.

- PMID 4606623.

- PMID 7043034.

- S2CID 46312750.

- S2CID 28975213.

- ^ OCLC 543168.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-679-43555-6.

- PMID 4569922.

- ^ OCLC 97780.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-8090-3817-6.

- ^ PMID 14232795.

The original observation of Makepeace et al. (1937) that progesterone inhibited ovulation in the rabbit was substantiated by Pincus and Chang (1953). In women, 300 mg of progesterone per day taken orally resulted in ovulation inhibition in 80% of cases (Pincus, 1956). The high dosage and frequent incidence of breakthrough bleeding limited the practical application of the method. Subsequently, the utilization of potent 19-norsteroids, which could be given orally, opened the field to practical oral contraception.

- ^ Nance K (16 October 2014). "Jonathan Eig on 'The Birth of the Pill'". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on 19 April 2019. Retrieved 19 October 2014.

- ^ "The Birth of the Pill". W. W. Norton & Company. Archived from the original on 11 October 2014. Retrieved 19 October 2014.

- ^ Manning K (17 October 2014). "Book review: 'The Birth of the Pill,' and the reinvention of sex, by Jonathan Eig". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 9 December 2022. Retrieved 25 August 2017.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-465-02582-4.

- ISBN 978-0-9801942-9-6.

- ISBN 978-0-275-98004-7.

- ISBN 978-0-316-56095-5.

- PMID 13477811.

- ^ PMID 13614060.

- ^ ISSN 0083-6729.

Ishikawa et al. (1957) employing the same regime of progesterone administration also observed suppression of ovulation in a proportion of the cases taken to laparotomy. Although sexual intercourse was practised freely by the subjects of our experiments and those of Ishikawa el al., no pregnancies occurred. Since ovulation presumably took place in a proportion of cycles, the lack of any pregnancies may be due to chance, but Ishikawa et al. (1957) have presented data indicating that in women receiving oral progesterone the cervical mucus becomes impenetrable to sperm.

- ^ PMID 5848673.

At the Fifth International Conference on Planned Parenthood in Tokyo, Pincus (1955) reported an ovulation inhibition by progesterone or norethynodrel1 taken orally by women. This report indicated the beginning of a new era in the history of contraception. ... That the cervical mucus might be one of the principal sites of action was suggested by the first studies of Pincus (1956, 1959) and of Ishikawa et al. (1957). These investigators found that no pregnancies occurred in women treated orally with large doses of progesterone, though ovulation was inhibited only in some 70% of the cases studied. ... The mechanism of protection in this method—and probably in that of Pincus (1956) and of Ishikawa et al. (1957)—must involve an effect on the cervical mucus and/or endometrium and Fallopian tubes.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-4696-4001-3. Archivedfrom the original on 15 July 2023. Retrieved 2 May 2019.

Still, neither of the two researchers was completely satisfied with the results. Progesterone tended to cause "premature menses," or breakthrough bleeding, in approximately 20 percent of the cycles, an occurrence that disturbed the patients and worried Rock.17 In addition, Pincus was concerned about the failure to inhibit ovulation in all the cases. Only large doses of orally administered progesterone could insure the suppression of ovulation, and these doses were expensive. The mass use of this regimen as a birth control method was thus seriously imperiled.

- PMID 356615.

- PMID 13380401.

- ^ OCLC 935295.

- PMID 13545267.

- S2CID 25550745.

- PMID 15673473.

- ^ S2CID 36533080.

- PMID 13640942.

- OCLC 935295.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-300-08943-1.

- PMID 5467404.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-8018-5876-5.

- PMID 14261427.

- .

- ISBN 978-0-385-14575-6.

- ^ US Food and Drug Administration (11 June 1970). "Statement of policy concerning oral contraceptive labeling directed to users". Federal Register. 35 (113): 9001–9003.

- ^ US Food and Drug Administration (31 January 1978). "Oral contraceptives; requirement for labeling directed to the patient". Federal Register. 43 (21): 4313–4334.

- ^ US Food and Drug Administration (25 May 1989). "Oral contraceptives; patient package insert requirement". Federal Register. 54 (100): 22585–22588.

- ^ "Prescriptive Authority for Pharmacists: Oral Contraceptives". Pharmacy Times. November 2018 Cough, Cold, & Flu. 84 (11). 19 November 2018. Archived from the original on 2 August 2019. Retrieved 2 August 2019.

- ^ "Pharmacist Prescribing for Hormonal Contraceptive Medications". NASPA. Archived from the original on 2 August 2019. Retrieved 2 August 2019.

- ^ "Pharmacists Authorized to Prescribe Birth Control in More States". NASPA. 4 May 2017. Archived from the original on 2 August 2019. Retrieved 2 August 2019.

- ^ "Doctor: Why I'm cheering about pharmacists in my state prescribing birth control pills". CNN. 30 January 2024. Archived from the original on 8 February 2024. Retrieved 11 February 2024.

- ^ a b "History of Schering AG". Archived from the original on 15 April 2008. Retrieved 6 December 2007.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ Van den Broeck K (5 March 2010). "Gynaecoloog Ferdinand Peeters: De vergeten stiefvader van de pil" [Gynecologist Ferdinand Peeters: The forgotten stepfather of the pil]. Knack (in Dutch). pp. 6–13. Extra #4. Archived from the original on 14 September 2022. Retrieved 14 September 2022.

- ^ Hope A (24 May 2010). "The little pill that could". Flanders Today. Archived from the original on 1 January 2021. Retrieved 28 December 2014.

- PMID 14471934.

- PMID 13889122.

- ^ PMID 13972503.

- ^ PMID 14471933.

- PMID 20789252.

"Medical News". BMJ. 2 (5258): 1032–1034. 1961.S2CID 51696624. - S2CID 8849008.

- ^ "Subsidizing birth control". Time. Vol. 78, no. 24. 15 December 1961. p. 55. Archived from the original on 5 February 2008.

- PMID 12306278.

- ^ "The Aids Generation: the pill takes priority?". Science Actualities. 2000. Archived from the original on 1 December 2006. Retrieved 7 September 2006.

- ^ "Djerassi on birth control in Japan – abortion 'yes,' pill 'no'" (Press release). Stanford University News Service. 14 February 1996. Archived from the original on 6 January 2007. Retrieved 23 August 2006.

- ^ Wudunn S (27 April 1999). "Japan's Tale of Two Pills: Viagra and Birth Control". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 19 April 2023. Retrieved 15 February 2017.

- ^ Efron S (3 June 1999). "Japan OKs Birth Control Pill After Decades of Delay". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 31 August 2022. Retrieved 31 August 2022.

- ^ Efron S (3 June 1999). "Japan OKs Birth Control Pill After Decades of Delay". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 10 August 2014. Retrieved 15 January 2015.

- ^ a b Hayashi A (20 August 2004). "Japanese Women Shun The Pill". CBS News. Archived from the original on 29 June 2006. Retrieved 12 June 2006.

- ^ "The Pill". Time. 7 April 1967. Archived from the original on 19 February 2005. Retrieved 16 June 2020.

- ^ Westhoff C (15 December 2015). "How Obamacare Explains the Rising Popularity of IUDs". Public Health Now at Columbia University. Archived from the original on 23 December 2021. Retrieved 17 June 2020.

- ^ "The Birth Control Pill: A History" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 December 2021. Retrieved 20 October 2018.

- (PDF) from the original on 29 May 2023. Retrieved 1 November 2017.

- ^ "The Pill". Equality Archive. 1 March 2017. Archived from the original on 23 December 2021. Retrieved 9 March 2017.

- ^ Weigel G (2002). The Courage to Be Catholic: Crisis, Reform, and the Renewal of the Church. Basic Books.

- ^ "Pillenverbot bleibt Streitfrage zwischen den Konfessionen". Focus Online. Archived from the original on 6 July 2021. Retrieved 22 March 2016.

- ^ a b c "1970 Year in Review". UPI. Archived from the original on 23 May 2009. Retrieved 8 April 2009.

- S2CID 145158114.

- doi:10.7273/nvgh-ca61. Archived from the originalon 14 January 2009. Retrieved 1 December 2017.

- ^ "The pill and the marriage revolution". The Clayman Institute for Gender Research. Archived from the original on 12 December 2017. Retrieved 1 December 2017.

- ^ PMID 12775044.

- S2CID 218496430.

- ^ Batt S (Spring 2005). "Pouring Drugs Down the Drain" (PDF). Herizons. 18 (4): 12–3. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 March 2012. Retrieved 4 December 2011.

- PMID 19469587.

- PMID 17030080.

- ^ Potts M, Marsh L (February 2010). "THE POPULATION FACTOR: How does it relate to climate change?" (PDF). OurPlanet.com. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 22 June 2015.

- ^ Cafaro P. "Alternative Climate Wedges – Population Wedge". Philip Cafaro. Archived from the original on 22 June 2015. Retrieved 22 June 2015.

- ^ Wire T (10 September 2009). "Contraception is 'greenest' technology". London School of Economics. Archived from the original on 22 June 2015. Retrieved 22 June 2015.

Further reading

- Black A, Guilbert E, Costescu D, Dunn S, Fisher W, Kives S, et al. (April 2017). "No. 329-Canadian Contraception Consensus Part 4 of 4 Chapter 9: Combined Hormonal Contraception". Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Canada. 39 (4): 229–268.e5. PMID 28413042.

External links

- The Birth Control Pill—CBC Digital Archives

- The Birth of the Pill—slide show by Life magazine