Eurasian chaffinch

| Common chaffinch | |

|---|---|

| |

| |

| Male (top) and female (bottom) in Hessen , Germany | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Passeriformes |

| Family: | Fringillidae |

| Subfamily: | Fringillinae |

| Genus: | Fringilla |

| Species: | F. coelebs

|

| Binomial name | |

| Fringilla coelebs | |

| |

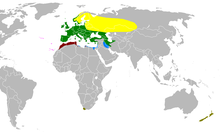

| Distribution map Summer Resident Winter Introduced canariensis spodiogenys | |

The Eurasian chaffinch, common chaffinch, or simply the chaffinch (Fringilla coelebs) is a common and widespread small

The chaffinch breeds in much of Europe, across the

The eggs and nestlings of the chaffinch are taken by a variety of mammalian and avian predators. Its large numbers and huge range mean that chaffinches are classed as of

Taxonomy

The Eurasian chaffinch was described by the Swedish naturalist Carl Linnaeus in 1758 in the 10th edition of his Systema Naturae under its current binomial name.[2] Fringilla is the Latin word for finch, while caelebs means unmarried or single. Linnaeus remarked that during the Swedish winter, only the female birds migrated south through Belgium to Italy.[2][3]

The English name comes from the

The

Subspecies

A number of subspecies of the Eurasian chaffinch have been described, based principally on the differences in the pattern and colour of the adult male plumage.

Within the "coelebs group", the gradual

The authors of a 2009

- coelebs group

- F. c. alexandrovi Zarudny, 1916 – northern Iran

- F. c. caucasica Serebrovski, 1925 – Balkans and northern Greece to northern Turkey, central and eastern Caucasus and northwestern Iran

- F. c. coelebs Asia Minor to Siberia

- F. c. balearica von Jordans, 1923 – Iberian Peninsula and the Balearic Islands

- F. c. gengleri O. Kleinschmidt, 1909 – British Isles

- F. c. sarda Rapine, 1925 – Sardinia

- F. c. schiebeli Erwin Stresemann, 1925 – southern Greece, Crete and western Turkey

- F. c. solomkoi Sushkin, 1913 – Crimean Peninsulaand southwestern Caucasus

- F. c. syriaca J. M. Harrisson, 1945 – Cyprus, southeastern Turkey to northern Iran and Jordan

- F. c. transcaspia Zarudny, 1916 – northeastern Iran and southwestern Turkmenistan

- F. c. tyrrhenica Schiebel, 1910 – Corsica

-

Male F. c. syriaca, Cyprus

-

Female F. c. syriaca, Cyprus

Description

The Eurasian chaffinch is about 14.5 cm (5.7 in) long, with a wingspan of 24.5–28.5 cm (9.6–11.2 in) and a weight of 18–29 g (0.63–1.02 oz).

After the autumn moult, the tips of the new feathers have a buff fringe that adds a brown cast to the coloured plumage. The ends of the feathers wear away over the winter so that by the spring breeding season the underlying brighter colours are displayed.[17][18] The eyes have dark brown irises and the legs are grey-brown. In winter the bill is a pale grey and slightly darker along the upper ridge or culmen, but in spring the bill becomes bluish-grey with a small black tip.[19]

The male of the subspecies resident in the British Isles (F. c. gengleri) closely resembles the nominate subspecies, but has a slightly darker mantle and underparts.[20]

The adult female is much duller in appearance than the male. The head and most of the upperparts are shades of grey-brown. The underparts are paler. The lower back and rump are a dull olive green. The wings and tail are similar to those of the male. The juvenile resembles the female.[21]

Voice

Males typically sing two or three different song types, and there are regional dialects also.[22][23]

The acquisition by the young Eurasian chaffinch of its song was the subject of an influential study by British ethologist William Thorpe. Thorpe determined that if the young common chaffinch is not exposed to the adult male's song during a certain critical period after hatching, it will never properly learn the song. He also found that in adult Eurasian chaffinches, castration eliminates the song, but injection of testosterone induces such birds to sing even in November, when they are normally silent.[24][25]

Distribution and habitat

The Eurasian chaffinch breeds in wooded areas where the July

This bird is not migratory in the milder parts of its range, but vacates the colder regions in winter. It forms loose flocks outside the breeding season, sometimes mixed with bramblings. It occasionally strays to eastern North America, although some sightings may be escapees.

Behaviour

Breeding

Eurasian chaffinches first breed when they are 1 year old. They are mainly monogamous and the pair-bond for residential subspecies such as gengleri sometimes persists from one year to the next.[30] The date for breeding is dependent on the spring temperature and is earlier in southwest Europe and later in the northeast. In Great Britain, most clutches are laid between late April and the middle of June. A male attracts a female to his territory through song.[31]

Nests are built entirely by the female and are usually located in the fork of a bush or a tree several metres above the ground.

In a study carried out in Britain using ring-recovery data, the survival rate for juveniles in their first year was 53 per cent, and the adult annual survival rate was 59 per cent.[36] From these figures the typical lifespan is only 3 years,[37] but the maximum age recorded is 15 years and 6 months for a bird in Switzerland.[38]

Feeding

Outside the breeding season, Eurasian chaffinches mainly eat seeds and other plant material that they find on the ground. They often forage in open country in large flocks. Common chaffinches seldom take food directly from plants and only very rarely use their feet for handling food.[39] During the breeding season, their diet switches to invertebrates, especially defoliating caterpillars. They forage in trees and also occasionally make short sallies to catch insects in the air.[39] The young are entirely fed with invertebrates which include caterpillars, aphids, earwigs, spiders and grubs (the larvae of beetles).[39]

Predators and parasites

The eggs and nestlings of the Eurasian chaffinch are predated by crows, Eurasian red and eastern grey squirrels, domestic cats and probably also by stoats and weasels. Clutches begun later in the spring suffer less predation, an effect that is believed to be due to the increased vegetation making nests more difficult to find.[40] Unlike the case for the closely related brambling, the common chaffinch is not parasitised by the common cuckoo.[41]

The protozoal parasite Trichomonas gallinae was known to infect pigeons and raptors, but beginning in Great Britain in 2005, carcasses of dead European greenfinches and common chaffinches were found to be infected with the parasite.[42] The disease spread and in 2008, infected carcasses were found in Norway, Sweden and Finland and a year later in Germany. The spread of the disease is believed to have been mediated by Eurasian chaffinches, as large numbers of the birds breed in northern Europe and winter in Great Britain.[43] In Great Britain, the number of infected carcasses recovered each year declined after a peak in 2006. There was a reduction in the number of European greenfinches but no significant decline in the overall number of common chaffinches.[44] A similar pattern occurred in Finland where, after the arrival of the disease in 2008, there was a reduction in the number of European greenfinches, but only a small change in the number of Eurasian chaffinches.[45]

Eurasian chaffinches can develop tumors on their feet and legs caused by the Fringilla coelebs papillomavirus.[46][47] The size of the papillomas range from a small nodule on a digit to a large growth involving both the foot and the leg. The disease is uncommon: in a 1973 study undertaken in the Netherlands, of around 25,000 common chaffinches screened, only 330 bore papillomas.[46]

Status

The Eurasian chaffinch has an extensive range, estimated at 7 million square kilometres (3.7 million square miles) and a large population including an estimated 130–240 million breeding pairs in Europe. Allowing for the birds breeding in Asia, the total population lies between 530 and 1,400 million individuals. There is no evidence of any serious overall decline in numbers, so the species is classified by the

Relationship to humans

The Eurasian chaffinch was once popular as a caged songbird and large numbers of wild birds were trapped and sold.[49] At the end of the 19th century, trapping even depleted the number of birds in London parks.[50] In 1882, the English publisher Samuel Orchart Beeton issued a guide on the care of caged birds and included the recommendation: "To parents and guardians plagued with a morose and sulky boy, my advice is, buy him a chaffinch."[49] Competitions were held where bets were placed on which caged common chaffinch would repeat its song the greatest number of times. The birds were sometimes blinded with a hot needle in the belief that this encouraged them to sing.[51] This practice is the subject of the poem The Blinded Bird by the English author Thomas Hardy, which contrasts the cruelty involved in blinding the birds with their zestful song.[52] In Great Britain, the practice of keeping Eurasian chaffinches as pets declined after the trapping of wild birds was outlawed by the Wild Birds Protection Acts of 1880 to 1896.[52][53]

The Eurasian chaffinch is still a popular pet bird in some European countries. In Belgium, the traditional sport of

References

- . Retrieved 12 November 2021.

- ^ a b Linnaeus, Carl (1758). Systema Naturæ per regna tria naturae, secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis (in Latin). Vol. 1 (10th ed.). Holmiae (Stockholm): Laurentii Salvii. p. 179.

- ISBN 978-1-4081-2501-4.

- ^ "Chaffinch". American Heritage Dictionary. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. Retrieved 25 November 2016.

- ISBN 978-0-500-23257-6.

- ^ "The Sherborne Missal - Pages 17 and 18". British Library. Retrieved 19 August 2013.

- ^ Turner, William (1903) [1544]. Turner on birds: a short and succinct history of the principal birds noticed by Pliny and Aristotle first published by Doctor William Turner, 1544 (in Latin and English). Translated by Evans, A.H. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 72–73. The Latin title of the 1544 edition was: Avium praecipuarum quarum apud Plinium et Aristotelem mentio est, brevis et succincta historia.

- ^ "sheld". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

- ^ a b Swainson, Charles (1885). Provincial names and folk lore of British birds. London: Trübner. pp. 62–63.

- ^ "alp". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

- ISBN 978-84-96553-68-2.

- ^ Gill, Frank; Donsker, David (eds.). "Finches, euphonias". World Bird List Version 5.3. International Ornithologists' Union. Retrieved 20 August 2015.

- .

- PMID 19632343.

- hdl:10651/50493.

- ^ a b Cramp (1994), p. 448.

- ^ a b c Cramp (1994), pp. 467–468.

- ^ Newton (1972), p. 19.

- ^ a b c Cramp (1994), p. 469.

- ^ Cramp (1994), pp. 472–473.

- ^ Cramp (1994), p. 449.

- hdl:2268/162278.

- hdl:2268/204048.

- .

- ^ Metzmacher, M. (1995). "La transmission du chant chez le Pinson des arbres (Fringilla c. coelebs): phase sensible et rôle des tuteurs chez les oiseaux captifs" (PDF). Alauda (in French). 63 (2): 123–134.

- ^ Cramp (1994), p. 450.

- JSTOR 1368385.

- ISBN 978-0-19-555885-2.

- ISBN 0-620-20731-0.

- ^ Cramp (1994), p. 457.

- ^ Newton (1972), p. 137.

- ^ a b c Cramp (1994), pp. 466–467.

- ^ Newton (1972), p. 141.

- ^ Newton (1972), pp. 141–142.

- ^ Newton 1972, p. 257, Appendix 11.

- .

- ^ "Chaffinch Fringilla coelebs [Linnaeus, 1758]". Bird Facts. British Trust for Ornithology. Retrieved 31 August 2023.

- ^ "European Longevity Records". Euring. Archived from the original on 2 June 2013. Retrieved 15 September 2013.

- ^ a b c Cramp 1994, pp. 455–456.

- ^ Newton (1972), p. 145.

- ^ Newton 1972, p. 28.

- PMID 20805869.

- S2CID 13343152.

- PMID 22966140.

- .

- ^ PMID 4702127.

- PMID 12208979.

- ^ "Eurasian Chaffinch Fringilla coelebs". Species factsheet. BirdLife International. Retrieved 6 September 2013.

- ^ a b Beeton, Samuel Orchart (1862). Beeton's book of birds : showing how to manage them in sickness and in health. London: Self-published. pp. 261–274.

- ^ Hudson, William Henry (1898). Birds in London. London: Longmans, Green and Co. p. 198.

- ^ Albin, Eleazar (1737). A Natural History of English Song-birds. London: A. Bettesworth and C. Hitch. pp. 25–26.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-7011-6907-7.

- ^ Marchant, James Robert Vernam; Watkins, Watkin (1897). Wild Birds Protection Acts, 1880-1896. London: R.H. Porter.

- ^ Dan, Bilefsky (21 May 2007). "One-Ounce Belgian Idols Vie for Most Tweets per Hour". The New York Times. Retrieved 15 August 2013.

Sources

- ISBN 978-0-19-854679-5.

- ISBN 978-0-00-213065-3.

Further reading

- Lynch, A; Plunkett, G M; Baker, A J; Jenkins, P F (1989). "A model of cultural evolution of chaffinch song derived with the meme concept". The American Naturalist. 133 (5): 634–653. S2CID 84322859.

- Marler, Peter (1956). "Behaviour of the chaffinch Fringilla coelebs". Behaviour. Supplement. Supplement 5 (5). Leiden: III–184. JSTOR 30039131.