Conradin

This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (October 2011) |

| Conradin | |

|---|---|

Elisabeth of Bavaria |

Conrad III (25 March 1252 – 29 October 1268), called the Younger or the Boy, but usually known by the diminutive Conradin (German: Konradin,

Early childhood

Conradin was born in Wolfstein, Bavaria, to Conrad IV of Germany and Elisabeth of Bavaria. Though he never succeeded his father as Roman-German king, he was recognized as king of Sicily and Jerusalem by supporters of the Hohenstaufens in 1254.

Having lost his father in 1254, he grew up at the court of his uncle and guardian,

Little is known of his appearance and character except that he was as "beautiful as Absalom, and spoke good Latin".[1] Although his father had entrusted him to the guardianship of the church, Pope Alexander IV forbade Conradin's election as Roman-German king and offered the Hohenstaufen lands in Germany to King Alfonso X of Castile.[1][2][3]

Political and military career

Having assumed the title of

Notwithstanding the defection of his uncle Louis and of other companions who returned to Germany, the threats of Clement IV, and a lack of funds, his cause seemed to prosper.[1] Proclaiming him King of Sicily, his partisans, among them Prince Henry of Castile, both in the north and south of Italy took up arms. Rome received his envoy with enthusiasm; and the young king himself received welcomes at Pavia, Pisa and Siena. In September 1267 a Spanish fleet under Frederick of Castile, and a number of knights from Pisa, and Spanish knights soldiering from Tunis, disembarked in the Sicilian city of Sciacca, and most of the island rebelled against the Angevin rule. Only Palermo and Messina remained loyal to Charles. The revolt spread to Calabria and Apulia. In November of the same year the Pope excommunicated him. His fleet won a victory over that of Charles I of Anjou, and in July 1268, Conradin himself entered Rome to a great and popular reception.

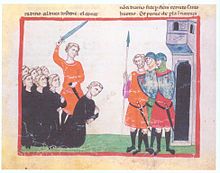

Having strengthened his forces, he marched towards Lucera to join the Saracen[1] troops settled there since the time of his grandfather. On 23 August 1268 his multinational army of Italian, Spanish, Roman, Arab and German troops encountered that of Charles at Tagliacozzo, in a hilly area of central Italy. The eagerness of Conradin's forces, notably that of the Spanish knights led by Infante Henry of Castile who mounted a triumphant charge and captured the Angevin banner, initially appeared to have secured victory. But their inability to see through Charles' ruse allowed the latter to ultimately emerge victorious once the elite of his army, the veteran French knights he had hidden behind a hill, entered the battle to the surprise of the enemy. Escaping from the field of battle, Conradin reached Rome, but acting on advice to leave the city he proceeded to Astura in an attempt to sail for Sicily. However, upon reaching his destination he was arrested and handed over to Charles, who imprisoned him in the Castel dell'Ovo in Naples, together with the inseparable Frederick of Baden. On 29 October 1268 Conradin and Frederick were beheaded.[4][2][3]

Legacy

With Conradin's death at 16, the direct (male) line of the

His hereditary Kingdom of Jerusalem passed to the heirs of his great-great-grandmother

According to a strict sense of legitimacy,

However, these claims met with little favor. Swabia, pawned by Conradin before his last expedition, was disintegrating as a territorial unit. He went unrecognized in Outremer, and Charles of Anjou was deeply entrenched in power in Southern Italy. Margrave Frederick proposed an invasion of Italy in 1269, and attracted some support from the Lombard Ghibellines, but his plans were never carried out, and he played no further part in Italian affairs.

Finally, Sicily passed to Charles of Anjou, but the Sicilian Vespers in 1282 resulted in dual claims on the Kingdom; the Aragonese heirs of Manfred retaining the island of Sicily and the Angevin party retaining the southern part of Italy, popularly called the Kingdom of Naples.[2][3]

In literature

Conradin was the subject of artistic interpretation in the nineteenth and early twentieth century. Several paintings and works of literature, especially poetry, depicted his military campaign and his execution. Felicia Hemans, best known for "The boy stood on the burning deck", wrote in 1824 "The Death of Conradin". Charles Swain wrote "Conradin" in 1832, a poem which inspired the first of "Three Tone Poems for Solo Piano" by Justin Henry Rubin.[6] Conradin : a philosophical ballad was written by C. R. Ashbee, dedicated to his patron and friend Colonel Shaw Hellier, and published in 1908 by Essex House Press, "one of the most significant private presses at work during the Arts and Crafts movement"[7]

The novel Põlev lipp (The Burning Banner) by Karl Ristikivi (1961; in Estonian) depicts Conradin's Italian campaign. A translation into the French by Jean Pascal Ollivry [1], entitled L'étendard en flammes, was published in Paris in 2005.[8]

Notes

- ^ After Conradin's demise, the remaining members of the Staufer dynasty were his half-aunts Margaret and Anna and the offspring of his-uncle Manfred. Both Anna and Manfred were the children of Frederick II by his mistress and fourth wife, Bianca Lancia. However, despite being born out of wedlock, they were legitimised by the posterior marriage of their parents on their mother's deathbed (which is attested in at least two medieval sources, the Chronicles of Salimbene di Adam and Mathew of Paris). This means that upon the deaths of Margaret in 1270 and Anna in 1307, Manfred's issue were the only ones who could have claimed dynastic rights to the House of Hohenstaufen, whose last member was indeed his son, Henry [Enrico], deceased on 31 October 1318 (as referenced by source n. 5).

- ^ Despite the fact that he usurped his nephew's crown, if Manfred is deemed legitimate, his sons and after them the offspring of his eldest daughter would have been Conradin's natural successors in Sicily and Swabia.

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Conradin". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 6 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 968–969.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-58642-181-6.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-135-94880-1.

- ^ Lukas Strehle (19 October 2011). Die Hinrichtung Konradins von Hohenstaufen – Reaktionen der Zeitgenossen und Rezeption der Nachwelt. Grin. Retrieved 28 February 2020.

- ^ Gregorovius, Ferdinand (2010) [1897], History of the City of Rome in the Middle Ages, Vol. 5, Part 2, Cambridge University Press.

- ^ https://www.d.umn.edu/~jrubin1/pJHR%20Three%20Tone%20Poems%20piano.pdf.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Conservation, Icon-The Institute of. "Assessment of The Essex House Press collection, Court Barn Museum". Icon - The Institute of Conservation. Retrieved 17 November 2023.

- ^ Karl Ristikivi. L'étendard en flammes Archived 5 June 2016 at the Wayback Machine. Traduit de l'estonien par Jean Pascal Ollivry. Paris: Alvik, 2005.

Bibliography

- F. W. Schirrmacher, Die letzten Hohenstaufen (Göttingen, 1871)

- K. Hampe, Geschichte Konradins von Hohenstaufen (Berlin, 1893)

- del Giudice, Il Giudizio e la condanna di Corradino (Naples, 1876)

- G. Cattaneo, Federico II di Svevia (Rome, 1992)

- E. Miller, Konradin von Hohenstaufen (Berlin, 1897)