Conservation biology

Conservation biology is the study of the conservation of nature and of

The

Origins

The term conservation biology and its conception as a new field originated with the convening of "The First International Conference on Research in Conservation Biology" held at the

Conservation biology and the concept of biological diversity (biodiversity) emerged together, helping crystallize the modern era of conservation science and policy.[10] The inherent multidisciplinary basis for conservation biology has led to new subdisciplines including conservation social science, conservation behavior and conservation physiology.[11] It stimulated further development of conservation genetics which Otto Frankel had originated first but is now often considered a subdiscipline as well.

Description

The rapid decline of established biological systems around the world means that conservation biology is often referred to as a "Discipline with a deadline".

Conservation biologists research and educate on the trends and process of

History

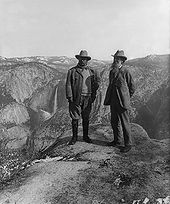

The conservation of natural resources is the fundamental problem. Unless we solve that problem, it will avail us little to solve all others.

– Theodore Roosevelt[20]

Natural resource conservation

Conscious efforts to conserve and protect global biodiversity are a recent phenomenon.

From this principle, conservation biologists can trace communal resource based ethics throughout cultures as a solution to communal resource conflict.

The Mauryan emperor Ashoka around 250 BC issued edicts restricting the slaughter of animals and certain kinds of birds, as well as opened veterinary clinics.

Conservation ethics are also found in early religious and philosophical writings. There are examples in the

Early naturalists

Natural history was a major preoccupation in the 18th century, with grand expeditions and the opening of popular public displays in Europe and North America. By 1900 there were 150 natural history museums in Germany, 250 in Great Britain, 250 in the United States, and 300 in France.[31] Preservationist or conservationist sentiments are a development of the late 18th to early 20th centuries.

Before Charles Darwin set sail on HMS Beagle, most people in the world, including Darwin, believed in special creation and that all species were unchanged.[32] George-Louis Leclerc was one of the first naturalist that questioned this belief. He proposed in his 44 volume natural history book that species evolve due to environmental influences.[32] Erasmus Darwin was also a naturalist who also suggested that species evolved. Erasmus Darwin noted that some species have vestigial structures which are anatomical structures that have no apparent function in the species currently but would have been useful for the species' ancestors.[32] The thinking of these early 18th century naturalists helped to change the mindset and thinking of the early 19th century naturalists.

By the early 19th century

Conservation movement

The modern roots of conservation biology can be found in the late 18th-century

Scientific conservation principles were first practically applied to the forests of

The

The term conservation came into widespread use in the late 19th century and referred to the management, mainly for economic reasons, of such natural resources as

One of the first conservation societies was the

In the

In the 20th century, Canadian civil servants, including Charles Gordon Hewitt[52] and James Harkin, spearheaded the movement toward wildlife conservation.[53]

In the 21st century professional conservation officers have begun to collaborate with indigenous communities for protecting wildlife in Canada.[54] Some conservation efforts are yet to fully take hold due to ecological neglect.[55][56][57] For example in the USA, 21st century bowfishing of native fishes, which amounts to killing wild animals for recreation and disposing of them immediately afterwards, remains unregulated and unmanaged.[48]

Global conservation efforts

In the mid-20th century, efforts arose to target individual species for conservation, notably efforts in

By the 1970s, led primarily by work in the United States under the

In 1980, a significant development was the emergence of the

By 1992, most of the countries of the world had become committed to the principles of conservation of biological diversity with the

Since 2000, the concept of

Ecology has clarified the workings of the

The last word in ignorance is the man who says of an animal or plant: "What good is it?" If the land mechanism as a whole is good, then every part is good, whether we understand it or not. If the biota, in the course of aeons, has built something we like but do not understand, then who but a fool would discard seemingly useless parts? To keep every cog and wheel is the first precaution of intelligent tinkering.

Concepts and foundations

Measuring extinction rates

Extinction rates are measured in a variety of ways. Conservation biologists measure and apply

The measure of ongoing species loss is made more complex by the fact that most of the Earth's species have not been described or evaluated. Estimates vary greatly on how many species actually exist (estimated range: 3,600,000–111,700,000) for actual numbers of species.

Systematic conservation planning

Systematic conservation planning is an effective way to seek and identify efficient and effective types of reserve design to capture or sustain the highest priority biodiversity values and to work with communities in support of local ecosystems. Margules and Pressey identify six interlinked stages in the systematic planning approach:[79]

- Compile data on the biodiversity of the planning region

- Identify conservation goals for the planning region

- Review existing conservation areas

- Select additional conservation areas

- Implement conservation actions

- Maintain the required values of conservation areas

Conservation biologists regularly prepare detailed conservation plans for

Conservation physiology: a mechanistic approach to conservation

Conservation physiology was defined by Steven J. Cooke and colleagues as:[11]

An integrative scientific discipline applying physiological concepts, tools, and knowledge to characterizing biological diversity and its ecological implications; understanding and predicting how organisms, populations, and ecosystems respond to environmental change and stressors; and solving conservation problems across the broad range of taxa (i.e. including microbes, plants, and animals). Physiology is considered in the broadest possible terms to include functional and mechanistic responses at all scales, and conservation includes the development and refinement of strategies to rebuild populations, restore ecosystems, inform conservation policy, generate decision-support tools, and manage natural resources.

Conservation physiology is particularly relevant to practitioners in that it has the potential to generate cause-and-effect relationships and reveal the factors that contribute to population declines.

Conservation biology as a profession

The

are immense fields unto themselves, but these disciplines are of prime importance to the practice and profession of conservation biology.Conservationists introduce

There is a movement in conservation biology suggesting a new form of leadership is needed to mobilize conservation biology into a more effective discipline that is able to communicate the full scope of the problem to society at large.[81] The movement proposes an adaptive leadership approach that parallels an adaptive management approach. The concept is based on a new philosophy or leadership theory steering away from historical notions of power, authority, and dominance. Adaptive conservation leadership is reflective and more equitable as it applies to any member of society who can mobilize others toward meaningful change using communication techniques that are inspiring, purposeful, and collegial. Adaptive conservation leadership and mentoring programs are being implemented by conservation biologists through organizations such as the Aldo Leopold Leadership Program.[82]

Approaches

Conservation may be classified as either

Also, non-interference may be used, which is termed a preservationist method. Preservationists advocate for giving areas of nature and species a protected existence that halts interference from the humans.[5] In this regard, conservationists differ from preservationists in the social dimension, as conservation biology engages society and seeks equitable solutions for both society and ecosystems. Some preservationists emphasize the potential of biodiversity in a world without humans.

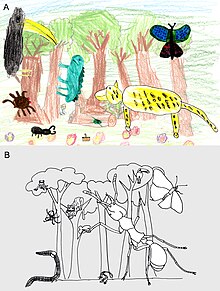

Ecological monitoring in conservation

Ecological monitoring is the systematic collection of data relevant to the ecology of a species or habitat at repeating intervals with defined methods.[84] Long-term monitoring for environmental and ecological metrics is an important part of any successful conservation initiative. Unfortunately, long-term data for many species and habitats is not available in many cases.[85] A lack of historical data on species populations, habitats, and ecosystems means that any current or future conservation work will have to make assumptions to determine if the work is having any effect on the population or ecosystem health. Ecological monitoring can provide early warning signals of deleterious effects (from human activities or natural changes in an environment) on an ecosystem and its species.[84] In order for signs of negative trends in ecosystem or species health to be detected, monitoring methods must be carried out at appropriate time intervals, and the metric must be able to capture the trend of the population or habitat as a whole.

Long-term monitoring can include the continued measuring of many biological, ecological, and environmental metrics including annual breeding success, population size estimates, water quality, biodiversity (which can be measured in many way, i.e. Shannon Index), and many other methods. When determining which metrics to monitor for a conservation project, it is important to understand how an ecosystem functions and what role different species and abiotic factors have within the system.[86] It is important to have a precise reason for why ecological monitoring is implemented; within the context of conservation, this reasoning is often to track changes before, during, or after conservation measures are put in place to help a species or habitat recover from degradation and/or maintain integrity.[84]

Another benefit of ecological monitoring is the hard evidence it provides scientists to use for advising policy makers and funding bodies about conservation efforts. Not only is ecological monitoring data important for convincing politicians, funders, and the public why a conservation program is important to implement, but also to keep them convinced that a program should be continued to be supported.[85]

There is plenty of debate on how conservation resources can be used most efficiently; even within ecological monitoring, there is debate on which metrics that money, time and personnel should be dedicated to for the best chance of making a positive impact. One specific general discussion topic is whether monitoring should happen where there is little human impact (to understand a system that has not been degraded by humans), where there is human impact (so the effects from humans can be investigated), or where there is data deserts and little is known about the habitats' and communities' response to human perturbations.[84]

The concept of bioindicators / indicator species can be applied to ecological monitoring as a way to investigate how pollution is affecting an ecosystem.[87] Species like amphibians and birds are highly susceptible to pollutants in their environment due to their behaviours and physiological features that cause them to absorb pollutants at a faster rate than other species. Amphibians spend parts of their time in the water and on land, making them susceptible to changes in both environments.[88] They also have very permeable skin that allows them to breath and intake water, which means they also take any air or water-soluble pollutants in as well. Birds often cover a wide range in habitat types annually, and also generally revisit the same nesting site each year. This makes it easier for researchers to track ecological effects at both an individual and a population level for the species.[89]

Many conservation researchers believe that having a long-term ecological monitoring program should be a priority for conservation projects, protected areas, and regions where environmental harm mitigation is used.[90]

Ethics and values

Conservation biologists are

A conservationist may be inspired by the resource conservation ethic,

Conservation priorities

The

While most in the community of conservation science "stress the importance" of

Biodiversity hotspots and coldspots are a way of recognizing that the spatial concentration of genes, species, and ecosystems is not uniformly distributed on the Earth's surface.[100] For example, "... 44% of all species of vascular plants and 35% of all species in four vertebrate groups are confined to 25 hotspots comprising only 1.4% of the land surface of the Earth."[101]

Those arguing in favor of setting priorities for coldspots point out that there are other measures to consider beyond biodiversity. They point out that emphasizing hotspots downplays the importance of the social and ecological connections to vast areas of the Earth's ecosystems where

Those in favor of the hotspot approach point out that species are irreplaceable components of the global ecosystem, they are concentrated in places that are most threatened, and should therefore receive maximal strategic protections.[109] This is a hotspot approach because the priority is set to target species level concerns over population level or biomass.[105][failed verification] Species richness and genetic biodiversity contributes to and engenders ecosystem stability, ecosystem processes, evolutionary adaptability, and biomass.[110] Both sides agree, however, that conserving biodiversity is necessary to reduce the extinction rate and identify an inherent value in nature; the debate hinges on how to prioritize limited conservation resources in the most cost-effective way.

Economic values and natural capital

Conservation biologists have started to collaborate with leading global

This method of measuring the global economic benefit of nature has been endorsed by the

The ecological credit crunch is a global challenge. The Living Planet Report 2008 tells us that more than three-quarters of the world's people live in nations that are ecological debtors – their national consumption has outstripped their country's biocapacity. Thus, most of us are propping up our current lifestyles, and our economic growth, by drawing (and increasingly overdrawing) upon the ecological capital of other parts of the world.

WWF Living Planet Report[113]

The inherent natural economy plays an essential role in sustaining humanity,[116] including the regulation of global atmospheric chemistry, pollinating crops, pest control,[117] cycling soil nutrients, purifying our water supply,[118] supplying medicines and health benefits,[119] and unquantifiable quality of life improvements. There is a relationship, a correlation, between markets and natural capital, and social income inequity and biodiversity loss. This means that there are greater rates of biodiversity loss in places where the inequity of wealth is greatest[120]

Although a direct market comparison of

Strategic species concepts

Keystone species

Some species, called a keystone species form a central supporting hub unique to their ecosystem.

Indicator species

An indicator species has a narrow set of ecological requirements, therefore they become useful targets for observing the health of an ecosystem. Some animals, such as

Government regulators, consultants, or

Umbrella and flagship species

An example of an umbrella species is the

Context and trends

Conservation biologists study trends and process from the

Holocene extinction

Conservation biologists are dealing with and have published

Status of oceans and reefs

Global assessments of coral reefs of the world continue to report drastic and rapid rates of decline. By 2000, 27% of the world's coral reef ecosystems had effectively collapsed. The largest period of decline occurred in a dramatic "bleaching" event in 1998, where approximately 16% of all the coral reefs in the world disappeared in less than a year.

These predictions will undoubtedly appear extreme, but it is difficult to imagine how such changes will not come to pass without fundamental changes in human behavior.

J.B. Jackson[17]: 11463

The oceans are threatened by acidification due to an increase in CO2 levels. This is a most serious threat to societies relying heavily upon oceanic

The prospects of averting mass extinction seems unlikely when "90% of all of the large (average approximately ≥50 kg), open ocean tuna, billfishes, and sharks in the ocean"

Groups other than vertebrates

Serious concerns also being raised about taxonomic groups that do not receive the same degree of social attention or attract funds as the vertebrates. These include fungal (including lichen-forming species),[153] invertebrate (particularly insect[15][154][155]) and plant communities[156] where the vast majority of biodiversity is represented. Conservation of fungi and conservation of insects, in particular, are both of pivotal importance for conservation biology. As mycorrhizal symbionts, and as decomposers and recyclers, fungi are essential for sustainability of forests.[153] The value of insects in the biosphere is enormous because they outnumber all other living groups in measure of species richness. The greatest bulk of biomass on land is found in plants, which is sustained by insect relations. This great ecological value of insects is countered by a society that often reacts negatively toward these aesthetically 'unpleasant' creatures.[157][158]

One area of concern in the insect world that has caught the public eye is the mysterious case of missing

Another highlight that links conservation biology to insects, forests, and climate change is the mountain pine beetle (Dendroctonus ponderosae) epidemic of British Columbia, Canada, which has infested 470,000 km2 (180,000 sq mi) of forested land since 1999.[106] An action plan has been prepared by the Government of British Columbia to address this problem.[162][163]

This impact [pine beetle epidemic] converted the forest from a small net carbon sink to a large net carbon source both during and immediately after the outbreak. In the worst year, the impacts resulting from the beetle outbreak in British Columbia were equivalent to 75% of the average annual direct forest fire emissions from all of Canada during 1959–1999.

— Kurz et al.[107]

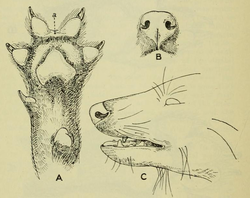

Conservation biology of parasites

A large proportion of parasite species are threatened by extinction. A few of them are being eradicated as pests of humans or domestic animals; however, most of them are harmless. Parasites also make up a significant amount of global biodiversity, given that they make up a large proportion of all species on earth,[164] making them of increasingly prevalent conservation interest. Threats include the decline or fragmentation of host populations,[165] or the extinction of host species. Parasites are intricately woven into ecosystems and food webs, thereby occupying valuable roles in ecosystem structure and function.[166][164]

Threats to biodiversity

Today, many threats to biodiversity exist. An acronym that can be used to express the top threats of present-day H.I.P.P.O stands for Habitat Loss, Invasive Species, Pollution, Human Population, and Overharvesting.

Human activities are associated directly or indirectly with nearly every aspect of the current extinction spasm.

Wake and Vredenburg[136]

However, human activities need not necessarily cause irreparable harm to the biosphere. With conservation management and planning for biodiversity at all levels, from genes to ecosystems, there are examples where humans mutually coexist in a sustainable way with nature.[180] Even with the current threats to biodiversity there are ways we can improve the current condition and start anew.

Many of the threats to biodiversity, including disease and climate change, are reaching inside borders of protected areas, leaving them 'not-so protected' (e.g.

See also

- Applied ecology

- Bird observatory

- Conservation-reliant species

- Ecological extinction

- Gene pool

- Genetic erosion

- Genetic pollution

- In-situ conservation

- Indigenous peoples: environmental benefits

- List of basic biology topics

- List of biological websites

- List of biology topics

- List of conservation organisations

- List of conservation topics

- Mutualisms and conservation

- Natural environment

- Nature conservation

- Nature conservation organizations by country

- Protected area

- Regional Red List

- Renewable resource

- Restoration ecology

- Tyranny of small decisions

- Water conservation

- Welfare biology

- Wildlife disease

- Wildlife management

- World Conservation Monitoring Centre

References

- ^ PMID 18198148.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-87893-800-1.

- JSTOR 1310054.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-87893-795-0.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-86542-371-8.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-87893-518-5.

- ^ OCLC 232001738.

- ^ J. Douglas. 1978. Biologists urge US endowment for conservation. Nature Vol. 275, 14 September 1978. Kat Williams . 1978. Natural Sciences. Science News. September 30, 1978.

- World Wildlife Fund, felt both genetics and ecology should be represented. Wilcox suggested use of a new term conservation biology, complementing Frankel's conception and coining of "conservation genetics", to encompass the application of biological sciences in general to conservation. Subsequently, Soulé and Wilcox wrote conceived the agenda for the meeting they jointly convened on September 6–9, 1978, titled First International Conference on Resesarch in Conservation Biology, in which the program described "The purpose of this conference is to accelerate and facilitate the development of a rigorous new discipline called conservation biology — a multidisciplinary field drawing its insights and methodology mostly from population ecology, community ecology, sociobiology, population genetics, and reproductive biology." This inclusion of topics at the meeting related to animal breeding reflected participation and support of the zoo and captive breeding communities.

- ISSN 1525-3244.

- ^ PMID 27293585.

- ISBN 978-0-316-64853-0.[page needed]

- S2CID 85324142.

- ^ PMID 20106856.

- ^ S2CID 30713492.

- ^ Millennium Ecosystem Assessment (2005). Ecosystems and Human Well-being: Biodiversity Synthesis. World Resources Institute, Washington, DC.[1]

- ^ PMID 18695220.

- ^ S2CID 16327687.

- ^ ISSN 2767-3197.

- ^ Theodore Roosevelt, Address to the Deep Waterway Convention Memphis, TN, October 4, 1907

- ^ "Biodiversity protection and preservation". ffem.fr. Archived from the original on 2016-10-18. Retrieved 2016-10-11.

- PMID 5699198.

- S2CID 37774648. Archived from the originalon 2009-03-26.

- ^ Mason, Rachel and Judith Ramos. (2004). Traditional Ecological Knowledge of Tlingit People concerning the Sockeye Salmon Fishery of the Dry Bay Area, A Cooperative Agreement Between Department of the Interior National Park Service and the Yakutat Tlingit Tribe, Final Report (FIS) Project 01-091, Yakutat, Alaska."Traditional Ecological Knowledge of Tlingit People Concerning the Sockeye Salmon Fishery of the Dry Bay Area" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-02-25. Retrieved 2009-01-07.

- S2CID 23587547.

- ISBN 978-0-226-90134-3.

- ISBN 978-0-87893-728-8.

- ^ Hamilton, E., and H. Cairns (eds). 1961. Plato: the collected dialogues. Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ

- ^ The Bible, Leviticus, 25:4-5

- ^ ISBN 978-0-415-14491-9.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-8018-6390-5.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-07-802426-9.

- ^ "Introduction to Conservation Biology and Biogeography". web2.uwindsor.ca.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-19-812437-5.

- ^ Stebbing, E.P (1922)The forests of India vol. 1, pp. 72-81

- ISBN 978-1-139-43460-7.

- ^ MUTHIAH, S. (Nov 5, 2007). "A life for forestry". The Hindu. Chennai, India. Archived from the original on November 8, 2007. Retrieved 2009-03-09.

- OCLC 301345427.

- ISSN 1016-6947. Archived from the originalon 2012-03-04.

- ^ Haines, Aubrey (1996). The Yellowstone Story: A History of Our First National Park: Volume 1 Revised Edition. Yellowstone Association for Natural Science, History of Education.

- ^ G. Baeyens; M. L. Martinez (2007). Coastal Dunes: Ecology and Conservation. Springer. p. 282.

- ^ Makel, Jo (2 February 2011). "Protecting seabirds at Bempton Cliffs". BBC News.

- ^ Newton A. 1899. The plume trade: borrowed plumes. The Times 28 January 1876; and The plume trade. The Times 25 February 1899. Reprinted together by the Society for the Protection of Birds, April 1899.

- ^ Newton A. 1868. The zoological aspect of game laws. Address to the British Association, Section D, August 1868. Reprinted [n.d.] by the Society for the Protection of Birds.

- ^ "Milestones". RSPB. Retrieved 19 February 2007.

- ISBN 978-0-7656-0187-2.

- ^ "History of the RSPB". RSPB. Retrieved 19 February 2007.

- ^ ISSN 1573-5133.

- ^ "Theodore Roosevelt and Conservation - Theodore Roosevelt National Park (U.S. National Park Service)". nps.gov. Retrieved 2016-10-04.

- ^ "Environmental timeline 1890–1920". runet.edu. Archived from the original on 2005-02-23.

- ISBN 978-0-7185-1548-5.

- ^ "Chrono-Biographical Sketch: Charles Gordon Hewitt". people.wku.edu. Retrieved 2017-05-07.

- ISBN 978-0-8020-7969-5.

- ^ Cecco, Leyland (19 April 2020). "Indigenous input helps save wayward grizzly bear from summary killing". The Guardian. Retrieved 23 April 2020.

- PMC 6533251.

- ISSN 0363-2415.

- ISSN 0363-2415.

- ^ A.R. Rabinowitz, Jaguar: One Man's Battle to Establish the World's First Jaguar Preserve, Arbor House, New York, N.Y. (1986)

- ISBN 978-0-300-05589-4.

- ^ "Chrono-Biographical Sketch: (Henry) Fairfield Osborn, Jr". wku.edu.

- ^ "the story of the virungas". cotf.edu. Retrieved 2022-07-10.

- ^ Akeley, C., 1923. In Brightest Africa New York, Doubleday. 188-249.

- ^ U.S. Endangered Species Act (7 U.S.C. § 136, 16 U.S.C. § 1531 et seq.) of 1973, Washington DC, U.S. Government Printing Office

- ^ "16 U.S. Code § 1531 - Congressional findings and declaration of purposes and policy". LII / Legal Information Institute.

- ^ "US Government Publishing Office - FDsys - Browse Publications". frwebgate.access.gpo.gov.

- JSTOR 3782224.

- ^ "Convention on Biological Diversity Official Page". Archived from the original on February 27, 2007.

- ISBN 978-0-395-57821-6.

- S2CID 205983813.

- JSTOR 3450043.

- .

- ISBN 978-0-691-08836-5.

- S2CID 29102370.

- PMID 26601195.

- S2CID 209562589.

- ^ S2CID 83906221.

- ^ "IUCN Red-list statistics (2006)". Archived from the original on June 30, 2006.

- critically endangeredor threatened for the purpose of these statistics.

- S2CID 4427223. Archived from the original(PDF) on 2009-02-25.

- ^ "Amphibian Conservation Action Plan" (PDF). 2007-07-04. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-07-04. Retrieved 2022-12-29.

- S2CID 36810103.

- ^ "Aldo Leopold Leadership Program". Woods Institute for the Environment, Stanford University. Archived from the original on 2007-02-17.

- ^ .

- ^ ISBN 978-1-139-44547-4.

- ^ S2CID 252889110.

- PMID 28190693.

- ISSN 1555-5275.

- ^ Macdonald, N. (2002). Frogwatch Teachers' guide to frogs as indicators of ecosystem health.

- ^ Begazo, A. (2022). Birds as indicators of Ecosystem Health. Retrieved December 14, 2022

- ISSN 1525-3244.

- PMID 18254846.

- ^ "The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species". Archived from the original on 2014-06-27. Retrieved 2013-10-20.

- ^ a b Vié, J. C.; Hilton-Taylor, C.; Stuart, S.N., eds. (2009). Wildlife in a Changing World – An Analysis of the 2008 IUCN Red List of Threatened Species (PDF). Gland, Switzerland: IUCN. p. 180. Retrieved December 24, 2010.

- ^ .

- S2CID 206523787.

- ^ Kearns, Carol Ann (2010). "Conservation of Biodiversity". Nature Education Knowledge. 3 (10): 7.

- ^ "Center for Biodiversity & Conservation | AMNH". American Museum of Natural History. Retrieved 2022-12-29.

- ^ .

- ^ .

- ISSN 1476-4687.

- S2CID 4414279.

- PMID 18231601.

- S2CID 1394295.

- PMID 18621701.

- ^ S2CID 23211536. Archived from the original(PDF) on 2018-10-01. Retrieved 2009-01-05.

- ^ S2CID 206513681.

- ^ S2CID 205212545.

- ^ The Global Conservation Fund Archived 2007-11-16 at the Wayback Machine is an example of funding organization that excludes biodiversity coldspots in its strategic campaign.

- ^ "The Biodiversity Hotspots". Archived from the original on 2008-12-22.

- PMID 17991772.

- ^ ISBN 978-92-79-08960-2.

- ^ "Gund Institute for Environment". www.uvm.edu. Retrieved 2022-12-29.

- ^ a b c WWF. "World Wildlife Fund" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on February 25, 2009. Retrieved January 8, 2009.

- ^ "From the Ecological Society of America (ESA)". Archived from the original on 2010-07-26. Retrieved 2008-12-30.

- ^ a b Millennium Ecosystem Assessment. (2005). Ecosystems and Human Well-being: Biodiversity Synthesis. World Resources Institute, Washington, DC.

- ^ "Millennium Ecosystem Assessment". Archived from the original on 2008-12-19. Retrieved 2008-12-30.

- ^ Black, Richard (2008-12-22). "Bees get plants' pests in a flap". BBC News. Retrieved 2010-04-01.

- S2CID 88786689.

- S2CID 37232884.

- PMID 17505535.

- ^ Staff of World Resources Program. (1998). Valuing Ecosystem Services Archived 2008-11-30 at the Wayback Machine. World Resources 1998-99.

- PMID 25077215.

- ^ "Valuation of Ecosystem services : A Backgrounder". Archived from the original on May 5, 2007.

- ^ Ecosystem Services: Estimated value in trillions Archived 2007-04-07 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Carbon capture, water filtration, other boreal forest ecoservices worth estimated $250 billion/year". EurekAlert!.

- ^ APIS, Volume 10, Number 11, November 1992, M.T. Sanford: Estimated value of honey bee pollination Archived 2007-02-02 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "The Hidden Economy". www.waikatoregion.govt.nz. Archived from the original on 2011-07-19. Retrieved 2022-12-29.

- ^ a b "Keystone Species". National Geographic Society. October 19, 2023.

- ^ P. K. Anderson. (1996). Competition, predation, and the evolution and extinction of Steller's Sea Cow, Hydrodamalis gigas. Marine Mammal Science, 11(3):391-394

- ^ PMID 17148336.

- .

- ISBN 978-0-87893-521-5.

- hdl:10261/135920.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-394-51312-6.[page needed]

- ISBN 978-2-940529-40-7.

- ^ PMID 18695221.

- ^ http://www.millenniumassessment.org[full citation needed][permanent dead link]

- ^ "National Survey Reveals Biodiversity Crisis – Scientific Experts Believe We Are In Midst of Fastest Mass Extinction in Earth's History". Archived from the original on 2007-06-07. Retrieved 2022-12-29.

- ISBN 978-0-19-854829-4.

- ^ a b Dell'Amore, Christine (30 May 2014). "Species Extinction Happening 1,000 Times Faster Because of Humans?". National Geographic. Archived from the original on May 31, 2014. Retrieved 11 October 2016.

- PMID 18695213.

- ^ Bentley, Molly (January 2, 2009). "Diamond clues to beasts' demise". BBC News.

- S2CID 206514910.

- ^ "An Analysis of Amphibians on the 2008 IUCN Red List. Summary of Key Findings". Global Amphibian Assessment. IUCN. Archived from the original on 2009-07-06.

- ^ S2CID 30162903.

- ^ a b Vince, Gaia. "A looming mass extinction caused by humans". BBC. Retrieved 11 October 2016.

- ^ Tate, Karl (19 June 2015). "The New Dying: How Human-Caused Extinction Affects the Planet (Infographic)". Live Science. Retrieved 11 October 2016.

- ^ Worrall, Simon (20 August 2016). "How the Current Mass Extinction of Animals Threatens Humans". National Geographic. Archived from the original on August 23, 2014. Retrieved 11 October 2016.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-643-06745-5.

- S2CID 206513451.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2011-06-05. Retrieved 2009-01-05.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)[full citation needed] - ISBN 0-85403-617-2 Download

- ^ a b "Orphans of Rio" (PDF). fungal-conservation.org. Retrieved 2011-07-09.

- S2CID 22863854.

- S2CID 38218672.

- S2CID 84923092.

- JSTOR 2386020.

- S2CID 43987366.

- ^ Society, National Geographic. "Honeybee." National Geographic. National Geographic, n.d. Web. 11 October 2016.

- S2CID 30877553.

- S2CID 170560082.

- ^ "British Columbia's Mountain Pine Beetle Action Plan 2006-2011" (PDF). Province of British Columbia. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-04-19.

- ^ "Mountain pine beetle". Province of British Columbia. January 26, 2024. Archived from the original on Dec 13, 2022.

- ^ S2CID 225517357.

- ISSN 1195-5449.

- S2CID 225345547.

- ^ a b c d "Threats to Biodiversity | GEOG 030: Geographic Perspectives on Sustainability and Human-Environment Systems, 2011". www.e-education.psu.edu. Retrieved 2016-10-07.

- PMID 18286193.

- S2CID 33259398.

- ^ "Asia's biodiversity vanishing into the marketplace" (Press release). Wildlife Conservation Society. February 9, 2004. Archived from the original on August 23, 2019. Retrieved October 13, 2016.

- ^ "Greatest threat to Asia's wildlife is hunting, scientists say" (Press release). Wildlife Conservation Society. April 9, 2002. Archived from the original on July 25, 2011. Retrieved October 13, 2016.

- ^ Hance, Jeremy (January 19, 2009). "Wildlife trade creating 'empty forest syndrome' across the globe". Mongabay.

- PMID 37419354.

- S2CID 254280225.

- S2CID 250940055.

- S2CID 4320526.

- ISSN 1476-4687.

- PMID 18666834.

- S2CID 22055213.

- OCLC 729066337.

- PMID 18955700.

- ISBN 978-0-412-02821-2.

- ^ S2CID 969382.

- John Roach (July 12, 2004). "By 2050 Warming to Doom Million Species, Study Says". National Geographic.

- S2CID 4400396.

Further reading

Scientific literature

- Bowen, Brian W. (1999). "Preserving genes, species, or ecosystems? Healing the fractured foundations of conservation policy". Molecular Ecology. 8 (s1): S5–S10. S2CID 33096004.

- Brooks T. M.; Mittermeier R. A.; Gerlach J.; Hoffmann M.; Lamoreux J. F.; Mittermeier C. G.; Pilgrim J. D.; Rodrigues A. S. L. (2006). "Global Biodiversity Conservation Priorities". Science. 313 (5783): 58–61. S2CID 5133902.

- Kareiva P.; Marvier M. (2003). "Conserving Biodiversity Coldspots" (PDF). American Scientist. 91 (4): 344–351. doi:10.1511/2003.4.344. Archived from the original(PDF) on September 6, 2006.

- Manlik, Oliver. (2019). "The Importance of Reproduction for the Conservation of Slow-Growing Animal Populations". Reproductive Sciences in Animal Conservation. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology. Vol. 1200. pp. 13–39. )

- McCallum M. L. (2008). "Amphibian Decline or Extinction? Current Declines Dwarf Background Extinction Rate" (PDF). Journal of Herpetology. 41 (3): 483–491. S2CID 30162903. Archived from the original(PDF) on 2008-12-17.

- McCallum M. L. (2015). "Vertebrate biodiversity losses point to a sixth mass extinction". Biodiversity and Conservation. 24 (10): 2497–2519. S2CID 254285797.

- McCallum, Malcolm L. (2021). "Turtle biodiversity losses suggest coming sixth mass extinction". Biodiversity and Conservation. 30 (5): 1257–1275. S2CID 233903598.

- Myers, Norman; Mittermeier, Russell A.; Mittermeier, Cristina G.; da Fonseca, Gustavo A. B.; Kent, Jennifer (2000). "Biodiversity hotspots for conservation priorities". Nature. 403 (6772): 853–8. S2CID 4414279.

- Brooks T. M.; Mittermeier R. A.; Gerlach J.; Hoffmann M.; Lamoreux J. F.; Mittermeier C. G.; Pilgrim J. D.; Rodrigues A. S. L. (2006). "Global Biodiversity Conservation Priorities". Science. 313 (5783): 58–61. S2CID 5133902.

- Kareiva P.; Marvier M. (2003). "Conserving Biodiversity Coldspots" (PDF). American Scientist. 91 (4): 344–351. doi:10.1511/2003.4.344. Archived from the original(PDF) on September 6, 2006.

- Mccallum, Malcolm L.; Bury, Gwendolyn W. (2013). "Google search patterns suggest declining interest in the environment". Biodiversity and Conservation. 22 (6–7): 1355–67. S2CID 15593201.

- Myers, Norman; Mittermeier, Russell A.; Mittermeier, Cristina G.; da Fonseca, Gustavo A. B.; Kent, Jennifer (2000). "Biodiversity hotspots for conservation priorities". Nature. 403 (6772): 853–8. S2CID 4414279.

- Wake, D. B.; Vredenburg, V. T. (2008). "Are we in the midst of the sixth mass extinction? A view from the world of amphibians". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 105 (Suppl 1): 11466–73. PMID 18695221.

Textbooks

- Groom, Martha J.; Meffe, Gary K.; Carroll, C. Ronald. (2006). Principles of Conservation Biology. Sunderland, Mass: Sinauer Associates. ISBN 978-0-87893-597-0.

- Norse, Elliott A.; Crowder, Larry B., eds. (2005). Marine conservation biology: the science of maintaining the sea's biodiversity. Washington, DC: Island Press. ISBN 978-1-55963-662-9.

- Primack, Richard B. (2004). A primer of Conservation Biology. Sunderland, Mass: Sinauer Associates. ISBN 978-0-87893-728-8.

- Primack, Richard B. (2006). Essentials of Conservation Biology. Sunderland, Mass: Sinauer Associates. ISBN 978-0-87893-720-2.

- Wilcox, Bruce A.; Soulé, Michael E.; Soulé, Michael E. (1980). Conservation Biology: an evolutionary-ecological perspective. Sunderland, Mass: Sinauer Associates. ISBN 978-0-87893-800-1.

- Kleiman, Devra G.; Thompson, Katerina V.; Baer, Charlotte Kirk (2010). Wild Mammals in Captivity. Chicago, Illinois: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-44009-5.

- Scheldeman, X.; van Zonneveld, M. (2010). Training Manual on Spatial Analysis of Plant Diversity and Distribution. Bioversity International. Archived from the original on 2011-09-27.

- Sodhi, Navjot S.; Ehrlich, Paul R. (2010). Conservation biology for all. Oxford University Press. A free textbook for download.

- Sutherland, W.; et al. (2015). Sutherland, William J; Dicks, Lynn V; Ockendon, Nancy; Smith, Rebecca K (eds.). What Works in Conservation. Open Book Publishers. ISBN 978-1-78374-157-1. A free textbook for download.

General non-fiction

- Christy, Bryan (2008). The Lizard King: The true crimes and passions of the world's greatest reptile smugglers. New York: Twelve. ISBN 978-0-446-58095-3.

- Nijhuis, Michelle (July 23, 2012). "Conservationists use triage to determine which species to save and not: Like battlefield medics, conservationists are being forced to explicitly apply triage to determine which creatures to save and which to let go". Scientific American. Retrieved 2017-05-07.

Periodicals

- Animal Conservation [2]

- Biological Conservation

- Conservation [3], a quarterly magazine of the Society for Conservation Biology

- Conservation and Society

- peer-reviewed journal of the Society for Conservation Biology

- Conservation Letters

- Diversity and Distributions

- Ecology and Society

Training manuals

- White, James Emery; Kapoor-Vijay, Promila (1992). Conservation biology: a training manual for biological diversity and genetic resources. London: Commonwealth Science Council, Commonwealth Secretariat. ISBN 978-0-85092-392-6.

External links

- Conservation Biology Institute (CBI)

- United Nations Environment Programme – World Conservation Monitoring Centre (UNEP-WCMC)

- The Center for Biodiversity and Conservation – American Museum of Natural History

- Sarkar, Sahotra. "Conservation Biology". In Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- Dictionary of the History of Ideas

- Conservationevidence.com – Free access to conservation studies