Conservatism

| Part of a series on |

| Conservatism |

|---|

|

Conservatism is a

Edmund Burke, an 18th-century Anglo-Irish statesman who opposed the French Revolution but supported the American Revolution, is credited as one of the forefathers of conservative thought in the 1790s along with Savoyard statesman Joseph de Maistre.[7] The first established use of the term in a political context originated in 1818 with François-René de Chateaubriand during the period of Bourbon Restoration that sought to roll back the policies of the French Revolution and establish social order.[8]

Conservatism has varied considerably as it has adapted itself to existing traditions and national cultures.[9] Thus, conservatives from different parts of the world, each upholding their respective traditions, may disagree on a wide range of issues.[10] Historically associated with right-wing politics, the term has been used to describe a wide range of views. Conservatism may be either libertarian or authoritarian,[11] populist or elitist,[12] progressive or reactionary,[13] moderate or extreme.[14]

Themes

Some political scientists, such as Samuel P. Huntington, have seen conservatism as situational. Under this definition, conservatives are seen as defending the established institutions of their time.[15] According to Quintin Hogg, the chairman of the British Conservative Party in 1959: "Conservatism is not so much a philosophy as an attitude, a constant force, performing a timeless function in the development of a free society, and corresponding to a deep and permanent requirement of human nature itself."[16] Conservatism is often used as a generic term to describe a "right-wing viewpoint occupying the political spectrum between [classical] liberalism and fascism".[1]

Not all conservatives consider a free society an important part of conservative philosophy, some having a more skeptical view of human nature. According to the Encyclopædia Britannica:

Edmund Burke, often called the father of conservative philosophy, shocked his contemporaries by insisting with brutal frankness that 'illusions' and 'prejudices' are socially necessary. He believed that most human beings are innately depraved, steeped in original sin, and unable to better themselves with their feeble reason. Better, he said, to rely on the 'latent wisdom' of prejudice, which accumulates slowly through the years, than to 'put men to live and trade each on his own private stock of reason.' Among such prejudices are those that favour an established church and a landed aristocracy; members of the latter, according to Burke, are the 'great oaks' and 'proper chieftains' of society, provided that they temper their rule with a spirit of timely reform and remain within the constitutional framework.'[17][excessive quote]

Tradition

Despite the lack of a universal definition, certain themes can be recognised as common across conservative thought. According to Michael Oakeshott:

To be conservative […] is to prefer the familiar to the unknown, to prefer the tried to the untried, fact to mystery, the actual to the possible, the limited to the unbounded, the near to the distant, the sufficient to the superabundant, the convenient to the perfect, present laughter to utopian bliss.[18]

Such traditionalism may be a reflection of trust in time-tested methods of social organisation, giving 'votes to the dead'.[19] Traditions may also be steeped in a sense of identity.[19]

Hierarchy

In contrast to the tradition-based definition of conservatism, some left-wing political theorists like Corey Robin define conservatism primarily in terms of a general defense of social and economic inequality.[20] From this perspective, conservatism is less an attempt to uphold old institutions and more "a meditation on—and theoretical rendition of—the felt experience of having power, seeing it threatened, and trying to win it back".[21] On another occasion, Robin argues for a more complex relation:

Conservatism is a defense of established hierarchies, but it is also fearful of those established hierarchies. It sees in their assuredness of power the source of corruption, decadence and decline. Ruling regimes require some kind of irritant, a grain of sand in the oyster, to reactivate their latent powers, to exercise their atrophied muscles, to make their pearls.[22]

In Conservatism: A Rediscovery (2022), political philosopher Yoram Hazony argues that, in a traditional conservative community, members have importance and influence to the degree they are honoured within the social hierarchy, which includes factors such as age, experience, and wisdom.[23] Conservatives often glorify hierarchies, as demonstrated in an aphorism by conservative philosopher Nicolás Gómez Dávila: "Hierarchies are celestial. In hell all are equal."[24] The word hierarchy has religious roots and translates to 'rule of a high priest.'[25]

Realism

Conservatism has been called a "philosophy of human imperfection" by Noël O'Sullivan, reflecting among its adherents a negative view of human nature and pessimism of the potential to improve it through 'utopian' schemes.[26] The "intellectual godfather of the realist right", Thomas Hobbes, argued that the state of nature for humans was "poor, nasty, brutish, and short", requiring centralised authority.[27]

Authority

Authority is a core tenet of conservatism.[28][29][30] More specifically, conservatives tend to believe in traditional authority. This form of authority, according to Max Weber, is "resting on an established belief in the sanctity of immemorial traditions and the legitimacy of those exercising authority under them".[31][32] Alexandre Kojève distinguishes between two different forms of traditional authority:

- The Authority of the Father—represented by actual fathers as well as conceptual fathers such as priests and monarchs.

- The Authority of the Master—represented by aristocrats and military commanders.[33]

Robert Nisbet acknowledges that the decline of traditional authority in the modern world is partly linked with the retreat of old institutions such as guild, order, parish, and family—institutions that formerly acted as intermediaries between the state and the individual.[34][35] Hannah Arendt claims that the modern world suffers an existential crisis with a "dramatic breakdown of all traditional authorities," which are needed for the continuity of an established civilisation.[36][37]

Reactionism

Reactionism is a tradition in

Some political scientists, such as Corey Robin, treat the words reactionary and conservative as synonyms.[41] Others, such as Mark Lilla, argue that reactionism and conservatism are distinct worldviews.[42] Francis Wilson defines conservatism as "a philosophy of social evolution, in which certain lasting values are defended within the framework of the tension of political conflict".[43]

Some reactionaries favor a return to the status quo ante, the previous political state of society, which that person believes possessed positive characteristics absent from contemporary society. An early example of a powerful reactionary movement was German Romanticism, which centered around concepts of organicism, medievalism, and traditionalism against the forces of rationalism, secularism, and individualism that were unleashed in the French Revolution.[44]

In political discourse, being a reactionary is generally regarded as negative; Peter King observed that it is "an unsought-for label, used as a torment rather than a badge of honor".[45] Despite this, the descriptor has been adopted by writers such as the Italian esoteric traditionalist Julius Evola,[46] the Austrian monarchist Erik von Kuehnelt-Leddihn,[47] the Colombian political theologian Nicolás Gómez Dávila, and the American historian John Lukacs.[48]

Intellectual history

Proto-conservatism

| Part of the Politics series on |

| Toryism |

|---|

|

In Great Britain, the

However, the Glorious Revolution of 1688 damaged this principle by establishing a constitutional government in England, leading to the hegemony of the Tory-opposed Whig ideology. Faced with defeat, the Tories reformed their movement. They adopted more moderate conservative positions, such as holding that sovereignty was vested in the three estates of Crown, Lords, and Commons rather than solely in the Crown.[49] Richard Hooker (1554–1600), Marquess of Halifax (1633–1695) and David Hume (1711–1776) were proto-conservatives of the period. Halifax promoted pragmatism in government whilst Hume argued against political rationalism and utopianism.[8][50]

Philosophical founders

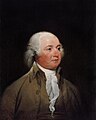

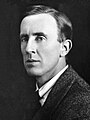

Edmund Burke (1729–1797) has been widely regarded as the philosophical founder of modern conservatism.[51][52] He served as the private secretary to the Marquis of Rockingham and as official pamphleteer to the Rockingham branch of the Whig party.[53] Together with the Tories, they were the conservatives in the late 18th century United Kingdom.[54]

Burke's views were a mixture of conservatism and republicanism. He supported the

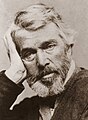

Another form of conservatism developed in France in parallel to conservatism in Britain. It was influenced by Counter-Enlightenment works by philosophers such as Joseph de Maistre (1753–1821) and Louis de Bonald (1754–1840). Many continental conservatives do not support separation of church and state, with most supporting state cooperation with the Catholic Church, such as had existed in France before the Revolution. Conservatives were also early to embrace nationalism, which was previously associated with liberalism and the Revolution in France.[59] Another early French conservative, François-René de Chateaubriand (1768–1848), espoused a romantic opposition to modernity, contrasting its emptiness with the 'full heart' of traditional faith and loyalty.[60] Elsewhere on the continent, German thinkers Justus Möser (1720–1794) and Friedrich von Gentz (1764–1832) criticized the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen that came of the Revolution. Opposition was also expressed by German idealists such as Adam Müller (1779–1829) and Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel (1771–1830), the latter inspiring both leftist and rightist followers.[61]

Both Burke and Maistre were critical of democracy in general, though their reasons differed. Maistre was pessimistic about humans being able to follow rules, while Burke was skeptical about humans' innate ability to make rules. For Maistre, rules had a divine origin, while Burke believed they arose from custom. The lack of custom for Burke, and the lack of divine guidance for Maistre, meant that people would act in terrible ways. Both also believed that liberty of the wrong kind led to bewilderment and political breakdown. Their ideas would together flow into a stream of anti-rationalist, romantic conservatism, but would still stay separate. Whereas Burke was more open to argumentation and disagreement, Maistre wanted faith and authority, leading to a more illiberal strain of thought.[62]

Ideological variants

Liberal conservatism

Liberal conservatism is a variant of conservatism that is strongly influenced by

Fiscal conservatism

Fiscal conservatism is the economic philosophy of prudence in government spending and debt.[68] In Reflections on the Revolution in France (1790), Edmund Burke argued that a government does not have the right to run up large debts and then throw the burden on the taxpayer:

[I]t is to the property of the citizen, and not to the demands of the creditor of the state, that the first and original faith of civil society is pledged. The claim of the citizen is prior in time, paramount in title, superior in equity. The fortunes of individuals, whether possessed by acquisition or by descent or in virtue of a participation in the goods of some community, were no part of the creditor's security, expressed or implied...[T]he public, whether represented by a monarch or by a senate, can pledge nothing but the public estate; and it can have no public estate except in what it derives from a just and proportioned imposition upon the citizens at large.

National conservatism

National conservatism is a political term used primarily in Europe to describe a variant of conservatism which concentrates more on national interests than standard conservatism as well as upholding cultural and ethnic identity,[69] while not being outspokenly ultra-nationalist or supporting a far-right approach.[70]

National conservatism is oriented towards upholding national sovereignty, which includes limited immigration and a strong national defence.[71] In Europe, national conservatives are usually eurosceptics.[72][73] Yoram Hazony has argued for national conservatism in his work The Virtue of Nationalism (2018).[74]

Traditionalist conservatism

Traditionalist conservatism, also known as classical conservatism, emphasizes the need for the principles of

Cultural conservatism

Cultural conservatives support the preservation of a

Social conservatism

Social conservatives believe that society is built upon a fragile network of relationships which need to be upheld through duty, traditional values, and established institutions; and that the government has a role in encouraging or enforcing traditional values or practices. A social conservative wants to preserve traditional morality and social mores, often by opposing what they consider radical policies or social engineering.[80] Some social-conservative stances are the following:

- Support of a embryonic stem cells research, and euthanasia.

- Support of bioconservatism and opposition to both eugenics and transhumanism.[81]

- Support of traditional family values, viewing the nuclear family model as society's foundational unit.

- Support of a traditional definition of marriage as being one man and one woman, and opposition to expansion of child adoption to couples in same-sex relationships.

- Support of drugs and prostitution and censorship of pornography.

- Support of organized religion and opposition to atheism and secularism, especially when militant.[82][83][84]

Religious conservatism

Religious conservatism principally applies the teachings of particular religions to politics—sometimes by merely proclaiming the value of those teachings, at other times by having those teachings influence laws.[85]

In most democracies, political conservatism seeks to uphold traditional family structures and social values. Religious conservatives typically oppose abortion, LGBT behaviour (or, in certain cases, identity), drug use,[86] and sexual activity outside of marriage. In some cases, conservative values are grounded in religious beliefs, and conservatives seek to increase the role of religion in public life.[87]

Paternalistic conservatism

Paternalistic conservatism is a strand in conservatism which reflects the belief that societies exist and develop organically and that members within them have obligations towards each other.

In more contemporary times, its proponents stress the importance of a

In 19th-century Germany, Chancellor Otto von Bismarck adopted a set of social programs, known as state socialism, which included insurance for workers against sickness, accident, incapacity, and old age. The goal of this conservative state-building strategy was to make ordinary Germans, not just the Junker aristocracy, more loyal to state and Emperor.[6] Chancellor Leo von Caprivi promoted a conservative agenda called the "New Course".[93]

Progressive conservatism

In the United States, Theodore Roosevelt has been identified as the main exponent of progressive conservatism. Roosevelt stated that he had "always believed that wise progressivism and wise conservatism go hand in hand".[94] The Republican administration of President William Howard Taft was progressive conservative, and he described himself as a believer in progressive conservatism.[94] President Dwight D. Eisenhower also declared himself an advocate of progressive conservatism.[95]

In Canada, a variety of conservative governments have been part of the Red Tory tradition, with Canada's former major conservative party being named the Progressive Conservative Party of Canada from 1942 to 2003.[96] Prime Ministers Arthur Meighen, R. B. Bennett, John Diefenbaker, Joe Clark, Brian Mulroney, and Kim Campbell led Red Tory federal governments.[96]

Authoritarian conservatism

Authoritarian conservatism refers to

Authoritarian conservative movements were prominent in the same era as fascism, with which it sometimes clashed.[106] Although both ideologies shared core values such as nationalism and had common enemies such as communism and materialism, there was nonetheless a contrast between the traditionalist nature of authoritarian conservatism and the revolutionary, palingenetic, and populist nature of fascism—thus it was common for authoritarian conservative regimes to suppress rising fascist and Nazi movements.[107] The hostility between the two ideologies is highlighted by the struggle for power in Austria, which was marked by the assassination of the ultra-Catholic dictator Engelbert Dollfuss by Austrian Nazis. Likewise, Croatian fascists assassinated King Alexander I of Yugoslavia.[108] In Romania, as the fascist Iron Guard was gaining popularity and Nazi Germany was making advances on the European political stage, King Carol II ordered the execution of Corneliu Zelea Codreanu and other top-ranking Romanian fascists.[109] The exiled German Emperor Wilhelm II was an enemy of Adolf Hitler, stating that Nazism made him ashamed to be a German for the first time in his life and referring to the Nazis as "a bunch of shirted gangsters" and "a mob … led by a thousand liars or fanatics".[110][111]

Political scientist Seymour Martin Lipset has examined the class basis of right-wing extremist politics in the 1920–1960 era. He reports:

Conservative or rightist extremist movements have arisen at different periods in modern history, ranging from the Horthyites in Hungary, the Christian Social Party of Dollfuss in Austria, Der Stahlhelm and other nationalists in pre-Hitler Germany, and Salazar in Portugal, to the pre-1966 Gaullist movements and the monarchists in contemporary France and Italy. The right extremists are conservative, not revolutionary. They seek to change political institutions in order to preserve or restore cultural and economic ones, while extremists of the centre [fascists/nazis] and left [communists/anarchists] seek to use political means for cultural and social revolution. The ideal of the right extremist is not a totalitarian ruler, but a monarch, or a traditionalist who acts like one. Many such movements in Spain, Austria, Hungary, Germany, and Italy have been explicitly monarchist […] The supporters of these movements differ from those of the centrists, tending to be wealthier, and more religious, which is more important in terms of a potential for mass support.[112]

During the Cold War, right-wing military dictatorships were prominent in Latin America, with most nations being under military rule by the middle of the 1970s.[114] One example of this was General Augusto Pinochet, who ruled over Chile from 1973 to 1990.[115] In the 21st century, the authoritarian style of government experienced a worldwide renaissance with conservative statesmen such as Vladimir Putin in Russia, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan in Turkey, Viktor Orbán in Hungary, Narendra Modi in India, and Donald Trump in the United States.[116]

National variants

Conservative parties vary widely from country to country in the goals they wish to achieve.[4] Both conservative and classical liberal parties tend to favour private ownership of property, in opposition to communist, socialist, and green parties, which favour communal ownership or laws regulating responsibility on the part of property owners. Where conservatives and liberals differ is primarily on social issues, where conservatives tend to reject behaviour that does not conform to some social norm. Modern conservative parties often define themselves by their opposition to liberal or socialist parties.

The United States usage of the term conservative is unique to that country.[117][further explanation needed]

Asia

India

Indian politics has long been dominated by aristocratic and religious elites in one of the most hierarchically organized nations in the world.[118][119] In modern times, the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), led by Narendra Modi, represents conservative politics. With over 170 million members as of October 2022,[120][121] the BJP is by far the world's largest political party.[122] It promotes Hindu nationalism, quasi-fascist Hindutva, a hostile foreign policy against Pakistan, and a conservative social and fiscal policy.[123]

Japan

| Part of a series on |

| Conservatism in Japan |

|---|

|

Conservatism has been the dominant political ideology throughout modern Japanese history.[124] The right-wing conservative Liberal Democratic Party has been the dominant ruling party since 1955, often referred to as the 1955 System.[125] Therefore, some experts consider Japan a democratically elected one-party state.[126]

A nation with deep militaristic roots that can be traced back to the aristocratic Samurai order and its bushido code of honour, Japan wields one of the most powerful militaries in Asia.[127] During the era of World War II, Japan was transformed into an ultranationalist, imperialist state that conquered much of east and southeast Asia.

Japan is the oldest continuing monarchy in the history of mankind, with Naruhito currently serving as Emperor of Japan.[128] In accordance with the principle of monarchy, Japanese society has an authoritarian family structure with a traditionalist fatherly authority that is primarily transferred to the oldest son.[129]

A highly developed and industrialised nation, Japan is more capitalistic and Western-orientated than other Asian nations, some experts considering Japan part of the Western world.[136] In 1960 a treaty was signed, establishing a military alliance between the United States and Japan.

Singapore

Singapore's only conservative party is the People's Action Party (PAP). It is currently in government and has been since independence in 1965. It promotes conservative values in the form of Asian democracy and Asian values.[137]

South Korea

| This article is part of a series on |

| Conservatism in South Korea |

|---|

|

South Korean politician and army general

When the conservative party was beaten by the opposition party in the general election, it changed its form again to follow the party members' demand for reforms. It became the New Korea Party, but it changed again one year later since the President Kim Young-sam was blamed by the citizen for the International Monetary Fund.[clarification needed] It changed its name to Grand National Party (GNP). Since the late Kim Dae-jung assumed the presidency in 1998, GNP had been the opposition party until Lee Myung-bak won the presidential election of 2007.

Europe

European conservatism has taken many different expressions. During the first half of the 20th century, as socialism was gaining power around the world, conservatism in countries such as Austria, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Portugal, and Spain transformed into the far-right, becoming more authoritarian and extreme.[139]

European nations, with the exception of Switzerland, have had a long monarchical tradition throughout history. Today, existing monarchies are Andorra, Belgium, Denmark, Liechtenstein, Luxembourg, Monaco, the Netherlands, Norway, Spain, Sweden, and the United Kingdom. Some reactionary movements in republican nations, such as Action Française in France, the Monarchist National Party in Italy, and the Black-Yellow Alliance in Austria, have advocated a restoration of the monarchy.

Austria

| Part of a series on |

| Conservatism in Austria |

|---|

|

Austrian conservatism originated with Prince

The

While having close ties to

Following World War II and the return to democracy, Austrian conservatives abandoned the authoritarianism of its past, believing in the principles of class collaboration and political compromise, while Austrian socialists also abandoned their extremism and distanced themselves from the totalitarianism of the Soviet Union.[148] The conservatives formed the Austrian People's Party, which has been the major conservative party in Austria ever since. In contemporary politics, the party was led by Sebastian Kurz, whom the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung nicknamed the "young Metternich".[149]

Belgium

Having its roots in the conservative

Denmark

| This article is part of a series on |

| Conservatism in Denmark |

|---|

|

Danish conservatism emerged with the political grouping Højre (literally "Right"), which due to its alliance with King Christian IX of Denmark dominated Danish politics and formed all governments from 1865 to 1901. When a constitutional reform in 1915 stripped the landed gentry of political power, Højre was succeeded by the Conservative People's Party of Denmark, which has since then been the main Danish conservative party.[154] Another Danish conservative party was the Free Conservatives, who were active between 1902 and 1920. Traditionally and historically, conservatism in Denmark has been more populist and agrarian than in Sweden and Norway, where conservatism has been more elitist and urban.[155]

The Conservative People's Party led the government coalition from 1982 to 1993. The party had previously been member of various governments from 1916 to 1917, 1940 to 1945, 1950 to 1953, and 1968 to 1971. The party was a junior partner in governments led by the Liberals from 2001 to 2011[156] and again from 2016 to 2019. The party is preceded by 11 years by the Young Conservatives (KU), today the youth movement of the party.

The Conservative People's Party had a stable electoral support close to 15 to 20% at almost all general elections from 1918 to 1971. In the 1970s it declined to around 5%, but then under the leadership of Poul Schlüter reached its highest popularity level ever in 1984, receiving 23% of the votes. Since the late 1990s the party has obtained around 5 to 10% of the vote. In 2022, the party received 5.5% of the vote.[157]

Conservative thinking has also influenced other Danish political parties. In 1995, the Danish People's Party was founded, based on a mixture of conservative, nationalist, and social-democratic ideas.[154] In 2015, the party New Right was established, professing a national-conservative attitude.[158]

The conservative parties in Denmark have always considered the monarchy a central institution in Denmark.[159][160][161][162]

Finland

The conservative party in Finland is the National Coalition Party. The party was founded in 1918, when several monarchist parties united. Although right-wing in the past, today it is a moderate liberal-conservative party. While advocating economic liberalism, it is committed to the social market economy.[163]

There has been strong

France

| This article is part of Conservatism in France |

|

Early conservatism in France focused on the rejection of the secularism of the French Revolution, support for the role of the Catholic Church, and the restoration of the monarchy.

After the

Religious tensions between Christian rightists and secular leftists heightened in the 1890–1910 era, but moderated after the spirit of unity in fighting World War I.[173] An authoritarian form of conservatism characterized the Vichy regime of 1940–1944 with heightened antisemitism, opposition to individualism, emphasis on family life, and national direction of the economy.[174]

Conservatism has been the major political force in France since World War II, although the number of conservative groups and their lack of stability defy simple categorization.[175] Following the war, conservatives supported Gaullist groups and parties, espoused nationalism, and emphasized tradition, social order, and the regeneration of France.[176] Unusually, post-war conservatism in France was formed around the personality of a leader—army officer Charles de Gaulle who led the Free French Forces against Nazi Germany—and it did not draw on traditional French conservatism, but on the Bonapartist tradition.[177] Gaullism in France continues under The Republicans (formerly Union for a Popular Movement), a party previously led by Nicolas Sarkozy, who served as President of France from 2007 to 2012 and whose ideology is known as Sarkozysm.[178]

In 2021, the French intellectual Éric Zemmour founded the nationalist party Reconquête, which has been described as a more elitist and conservative version of Marine Le Pen's National Rally.[179]

Germany

| This article is part of a series on |

| Conservatism in Germany |

|---|

|

Germany was the heart of the reactionary Romantic movement that swept Europe in the aftermath of the progressive Age of Enlightenment and its culmination in the anti-conservative French Revolution.[44] German Romanticism was deeply organicist and medievalist, finding expression philosophically among the Old Hegelians and judicially in the German historical school.[180] Prominent conservative exponents were Friedrich Schlegel, Novalis, Wilhelm Heinrich Wackenroder, Friedrich Carl von Savigny, and Adam Müller.[181]

During the second half of the 19th century, German conservatism developed alongside nationalism, culminating in Germany's victory over France in the Franco-Prussian War, the creation of the unified German Empire in 1871, and the simultaneous rise of Otto von Bismarck on the European political stage. Bismarck's "balance of power" model maintained peace in Europe for decades at the end of the 19th century.[182] His "revolutionary conservatism" was a conservative state-building strategy, based on class collaboration and designed to make ordinary Germans—not just the Junker aristocracy—more loyal to state and Emperor.[6] He created the modern welfare state in Germany in the 1880s.[183] According to scholars, his strategy was:

granting social rights to enhance the integration of a hierarchical society, to forge a bond between workers and the state so as to strengthen the latter, to maintain traditional relations of authority between social and status groups, and to provide a countervailing power against the modernist forces of liberalism and socialism.[184]

Bismarck also enacted universal manhood suffrage in the new German Empire in 1871.[185] He became a great hero to German conservatives, who erected many monuments to his memory after he left office in 1890.[186]

During the interwar period—after Germany's defeat in World War I, the abdication of Emperor Wilhelm II, and the introduction of parliamentary democracy—German conservatives experienced a cultural crisis and felt uprooted by a progressively modernist world.[187] This angst was expressed philosophically in the Conservative Revolution movement with prominent exponents such as historian Oswald Spengler, jurist Carl Schmitt, and author Ernst Jünger.[188] The major conservative party of this era was the reactionary German National People's Party, who advocated a restored monarchy.[189]

With the rise of Nazism in 1933, traditional agrarian movements faded and were supplanted by a more command-based economy and forced social integration. Adolf Hitler succeeded in garnering the support of many German industrialists; but prominent traditionalists, including military officers Claus von Stauffenberg and Henning von Tresckow, pastor Dietrich Bonhoeffer, Bishop Clemens August Graf von Galen, and monarchist Carl Friedrich Goerdeler, openly and secretly opposed his policies of euthanasia, genocide, and attacks on organized religion.[190] The former German Emperor Wilhelm II was highly critical of Hitler, writing in 1938:

There's a man alone, without family, without children, without God ... He builds legions, but he doesn't build a nation. A nation is created by families, a religion, traditions: it is made up out of the hearts of mothers, the wisdom of fathers, the joy and the exuberance of children ... This man could bring home victories to our people each year, without bringing them either glory or danger. But of our Germany, which was a nation of poets and musicians, of artists and soldiers, he has made a nation of hysterics and hermits, engulfed in a mob and led by a thousand liars or fanatics.[110]

Post-World War II Germany developed a special form of conservatism called ordoliberalism, which is centered around the concept of ordered liberty.[191] Neither socialist nor capitalist, it promotes a compromise between state and market, and argues that the national culture of a country must be taken into account when implementing economic policies.[192] Alexander Rüstow and Wilhelm Röpke were two prominent exponents of this economic theory, and its implementation is largely credited as a reason behind the German miracle—the rapid reconstruction and development of the war-wrecked economies of West Germany and Austria after World War II.[193]

More recently, the work of conservative Christian Democratic Union leader and Chancellor Helmut Kohl helped bring about German reunification, along with the closer European integration in the form of the Maastricht Treaty. Today, German conservatism is often associated with politicians such as Chancellor Angela Merkel, whose tenure was marked by attempts to save the common European currency (Euro) from demise. The German conservatives were divided under Merkel due to the refugee crisis in Germany, and many conservatives in the CDU/CSU opposed the immigration policies developed under Merkel.[194] The 2020s also saw the rise of the right-wing populist Alternative for Germany.[195]

Greece

| This article is part of a series on |

| Conservatism in Greece |

|---|

|

The main inter-war conservative party was called the

In 1952, Marshal Alexandros Papagos created the Greek Rally as an umbrella for the right-wing forces. The Greek Rally came to power in 1952 and remained the leading party in Greece until 1963. After Papagos' death in 1955, it was reformed as the National Radical Union under Konstantinos Karamanlis. Right-wing governments backed by the palace and the army overthrew the Centre Union government in 1965 and governed the country until the establishment of the far-right Greek junta (1967–1974). After the regime's collapse in August 1974, Karamanlis returned from exile to lead the government and founded the New Democracy party. The new conservative party had four objectives: to confront Turkish expansionism in Cyprus, to reestablish and solidify democratic rule, to give the country a strong government, and to make a powerful moderate party a force in Greek politics.[196]

The

Hungary

The dominance of the political right of

Between 1919 and 1944 Hungary was a rightist country. Forged out of a counter-revolutionary heritage, its governments advocated a "nationalist Christian" policy; they extolled heroism, faith, and unity; they despised the French Revolution, and they spurned the liberal and socialist ideologies of the 19th century. The governments saw Hungary as a bulwark against bolshevism and bolshevism's instruments: socialism, cosmopolitanism, and Freemasonry. They perpetrated the rule of a small clique of aristocrats, civil servants, and army officers, and surrounded with adulation the head of the state, the counterrevolutionary Admiral Horthy.[198]

Horthy's authoritarian conservative regime suppressed communists and fascists alike, banning the Hungarian Communist Party as well as the fascist Arrow Cross Party. The fascist leader Ferenc Szálasi was repeatedly imprisoned at Horthy's command.[101]

Iceland

Founded in 1924 as the Conservative Party, Iceland's Independence Party adopted its current name in 1929 after the merger with the Liberal Party. From the beginning, they have been the largest vote-winning party, averaging around 40%. They combined liberalism and conservatism, supported nationalization of infrastructure, and advocated class collaboration. While mostly in opposition during the 1930s, they embraced economic liberalism, but accepted the welfare state after the war and participated in governments supportive of state intervention and protectionism. Unlike other Scandanivian conservative (and liberal) parties, it has always had a large working-class following.[199] After the financial crisis in 2008, the party has sunk to a lower support level at around 20–25%.

Italy

| This article is part of a series on |

| Conservatism in Italy |

|---|

|

After unification, Italy was governed successively by the Historical Right, which represented conservative, liberal-conservative, and conservative-liberal positions, and the Historical Left.

After World War I, the country saw the emergence of its first mass parties, notably including the Italian People's Party (PPI), a Christian-democratic party that sought to represent the Catholic majority, which had long refrained from politics. The PPI and the Italian Socialist Party decisively contributed to the loss of strength and authority of the old liberal ruling class, which had not been able to structure itself into a proper party: the Liberal Union was not coherent and the Italian Liberal Party came too late.

In 1921,

In 1946, a referendum was held concerning the fate of the monarchy. While southern Italy and parts of northern Italy were royalist, other parts, especially in central Italy, were predominantly republican. The outcome was 54–46% in favour of a republic, leading to a collapse of the monarchy.[204]

After World War II, the centre-right was dominated by the centrist party Christian Democracy (DC), which included both conservative and centre-left elements. With its landslide victory over the Italian Socialist Party and the Italian Communist Party in 1948, the political centre was in power. In Denis Mack Smith's words, it was "moderately conservative, reasonably tolerant of everything which did not touch religion or property, but above all Catholic and sometimes clerical". It dominated politics until DC's dissolution in 1994.[205][206] Among DC's frequent allies, there was the conservative-liberal Italian Liberal Party. At the right of the DC stood parties like the royalist Monarchist National Party and the post-fascist Italian Social Movement.

In 1994, entrepreneur and media tycoon Silvio Berlusconi founded the liberal-conservative party Forza Italia (FI). He won three elections in 1994, 2001, and 2008, governing the country for almost ten years as prime minister. FI formed a coalitions with several parties, including the national-conservative National Alliance (AN), heir of the MSI, and the regionalist Lega Nord (LN). FI was briefly incorporated, along with AN, in The People of Freedom party and later revived in the new Forza Italia.[207] After the 2018 general election, the LN and the Five Star Movement formed a populist government, which lasted about a year.[208] In the 2022 general election, a centre-right coalition came to power, this time dominated by Brothers of Italy (FdI), a new national-conservative party born on the ashes of AN. Consequently, FdI, the re-branded Lega, and FI formed a government under FdI leader Giorgia Meloni.

Luxembourg

Luxembourg's major conservative party, the Christian Social People's Party, was formed as the Party of the Right in 1914 and adopted its present name in 1945. It was consistently the largest political party in Luxembourg and dominated politics throughout the 20th century.[209]

Netherlands

Liberalism has been strong in the Netherlands. Therefore, rightist parties are often liberal-conservative or conservative-liberal. One example is the People's Party for Freedom and Democracy. Even the right-wing populist and far-right Party for Freedom, which dominated the 2023 election, supports liberal positions such as gay rights, abortion, and euthanasia.[210]

Norway

The Conservative Party of Norway (Norwegian: Høyre, literally "Right") was formed by the old upper-class of state officials and wealthy merchants to fight the populist democracy of the Liberal Party, but it lost power in 1884, when parliamentarian government was first practiced. It formed its first government under parliamentarism in 1889 and continued to alternate in power with the Liberals until the 1930s, when Labour became the dominant party. It has elements both of paternalism, stressing the responsibilities of the state, and of economic liberalism. It first returned to power in the 1960s.[211] During Kåre Willoch's premiership in the 1980s, much emphasis was laid on liberalizing the credit and housing market and abolishing the NRK TV and radio monopoly, while supporting law and order in criminal justice and traditional norms in education.[212]

Russia

| This article is part of a series on |

| Conservatism in Russia |

|---|

|

Under

Putin has also promoted new think tanks that bring together like-minded intellectuals and writers. For example, the Izborsky Club, founded in 2012 by Alexander Prokhanov, stresses Russian nationalism, the restoration of Russia's historical greatness, and systematic opposition to liberal ideas and policies.[215] Vladislav Surkov, a senior government official, has been one of the key ideologues during Putin's presidency.[216]

In cultural and social affairs, Putin has collaborated closely with the Russian Orthodox Church.[217][218] Under Patriarch Kirill of Moscow, the Church has backed the expansion of Russian power into Crimea and eastern Ukraine.[219] More broadly, The New York Times reports in September 2016 how the Church's policy prescriptions support the Kremlin's appeal to social conservatives:

A fervent foe of homosexuality and any attempt to put individual rights above those of family, community, or nation, the Russian Orthodox Church helps project Russia as the natural ally of all those who pine for a more secure, illiberal world free from the tradition-crushing rush of globalization, multiculturalism, and women's and gay rights.[220]

Sweden

| This article is part of a series on |

| Conservatism in Sweden |

|---|

|

In the early 19th century, Swedish conservatism developed alongside Swedish Romanticism. The historian Erik Gustaf Geijer, an exponent of Gothicism, glorified the Viking Age and the Swedish Empire,[221] and the idealist philosopher Christopher Jacob Boström became the chief ideologue of the official state doctrine, which dominated Swedish politics for almost a century.[222] Other influential Swedish conservative Romantics were Esaias Tegnér and Per Daniel Amadeus Atterbom.

Early parliamentary conservatism in Sweden was explicitly elitist. Indeed, the

Once a democratic system was in place, Swedish conservatives sought to combine traditional elitism with modern populism. Sweden's most renowned political scientist, the conservative politician Rudolf Kjellén, coined the terms geopolitics and biopolitics in relation to his organic theory of the state.[224] He also developed the corporatist-nationalist concept of Folkhemmet ('the home of the people'), which became the single most powerful political concept in Sweden throughout the 20th century, although it was adopted by the Social Democratic Party who gave it a more socialist interpretation.[225]

After a brief grand coalition between Left and Right during World War II, the centre-right parties struggled to cooperate due to their ideological differences: the agrarian populism of the Centre Party, the urban liberalism of the Liberal People's Party, and the liberal-conservative elitism of the Moderate Party (the old Conservative Party). However, in 1976 and in 1979, the three parties managed to form a government under Thorbjörn Fälldin—and again in 1991, this time under aristocrat Carl Bildt and with support from the newly founded Christian Democrats, the most conservative party in contemporary Sweden.[226]

In modern times,

Switzerland

| This article is part of a series on |

| Conservatism in Switzerland |

|---|

|

In some aspects, Swiss conservatism is unique, as Switzerland is an old federal republic born from historically sovereign cantons, comprising three major nationalities, and adhering to the principle of Swiss neutrality.

There are a number of conservative parties in Switzerland's parliament, the Federal Assembly. These include the largest ones: the Swiss People's Party (SVP),[233] the Christian Democratic People's Party (CVP),[234] and the Conservative Democratic Party of Switzerland (BDP),[235] which is a splinter of the SVP created in the aftermath to the election of Eveline Widmer-Schlumpf as Federal Council.[235]

The SVP was formed from the 1971 merger of the Party of Farmers, Traders and Citizens, formed in 1917, and the smaller Democratic Party, formed in 1942. The SVP emphasized agricultural policy and was strong among farmers in German-speaking Protestant areas. As Switzerland considered closer relations with the European Union in the 1990s, the SVP adopted a more militant protectionist and isolationist stance. This stance has allowed it to expand into German-speaking Catholic mountainous areas.[236] The Anti-Defamation League, a non-Swiss lobby group based in the United States has accused them of manipulating issues such as immigration, Swiss neutrality, and welfare benefits, awakening antisemitism and racism.[237] The Council of Europe has called the SVP "extreme right", although some scholars dispute this classification. For instance, Hans-Georg Betz describes it as "populist radical right".[238] The SVP has been the largest party since 2003.

Ukraine

The authoritarian

United Kingdom

| This article is part of a series on |

| Conservatism in the United Kingdom |

|---|

|

| Part of the Politics series on |

| Toryism |

|---|

|

Modern English conservatives celebrate Anglo-Irish statesman Edmund Burke as their intellectual father. Burke was affiliated with the Whig Party, which eventually split amongst the Liberal Party and the Conservative Party, but the modern Conservative Party is generally thought to derive primarily from the Tories, and the MPs of the modern conservative party are still frequently referred to as Tories.[240]

Shortly after Burke's death in 1797, conservatism was revived as a mainstream political force as the Whigs suffered a series of internal divisions. This new generation of conservatives derived their politics not from Burke, but from his predecessor, the Viscount Bolingbroke (1678–1751), who was a Jacobite and traditional Tory, lacking Burke's sympathies for Whiggish policies such as Catholic emancipation and American independence (famously attacked by Samuel Johnson in "Taxation No Tyranny").[240]

In the first half of the 19th century, many newspapers, magazines, and journals promoted

Conservatism evolved after 1820, embracing

Some conservatives lamented the passing of a pastoral world where the ethos of

In 1834, Tory

In the second half of the 19th century, the Liberal Party faced political schisms, especially over Irish Home Rule. Leader William Gladstone (himself a former Peelite) sought to give Ireland a degree of autonomy, a move that elements in both the left and right-wings of his party opposed. These split off to become the Liberal Unionists (led by Joseph Chamberlain), forming a coalition with the Conservatives before merging with them in 1912. The Liberal Unionist influence dragged the Conservative Party towards the left as Conservative governments passed a number of progressive reforms at the turn of the 20th century. By the late 19th century, the traditional business supporters of the Liberal Party had joined the Conservatives, making them the party of business and commerce as well.

After a period of Liberal dominance before the

In the 1980s, the Conservative government of

Latin America

Conservative elites have long dominated Latin American nations. Mostly, this has been achieved through control of civil institutions, the Catholic Church, and the military, rather than through party politics. Typically, the Church was exempt from taxes and its employees immune from civil prosecution. Where conservative parties were weak or non-existent, conservatives were more likely to rely on military dictatorship as a preferred form of government.[252]

However, in some nations where the elites were able to mobilize popular support for conservative parties, longer periods of political stability were achieved. Chile, Colombia, and Venezuela are examples of nations that developed strong conservative parties. Argentina, Brazil, El Salvador, and Peru are examples of nations where this did not occur.[253]

Louis Hartz explained conservatism in Latin American nations as a result of their settlement as feudal societies.[254]

Brazil

| This article is part of a series on |

| Conservatism in Brazil |

|---|

|

Conservatism in Brazil originates from the cultural and historical tradition of Brazil, whose cultural roots are

The military dictatorship in Brazil was established on April 1, 1964, after a coup d'état by the Brazilian Army with support from the United States government, and it lasted for 21 years, until March 15, 1985. The coup received support from almost all high-ranking members of the military along with conservative sectors in society, such as the Catholic Church and anti-communist civilian movements among the Brazilian middle and upper classes. The dictatorship reached the height of its popularity in the 1970s with the so-called Brazilian Miracle. Brazil's military government provided a model for other military regimes throughout Latin America, being systematized by the "National Security Doctrine", which was used to justify the military's actions as operating in the interest of national security in a time of crisis.[256]

In contemporary politics, a

Chile

Chile's conservative party, the

Colombia

The Colombian Conservative Party, founded in 1849, traces its origins to opponents of General Francisco de Paula Santander's 1833–1837 administration. While the term "liberal" had been used to describe all political forces in Colombia, the conservatives began describing themselves as "conservative liberals" and their opponents as "red liberals". From the 1860s until the present, the party has supported strong central government and the Catholic Church, especially its role as protector of the sanctity of the family, and opposed separation of church and state. Its policies include the legal equality of all men, the citizen's right to own property, and opposition to dictatorship. It has usually been Colombia's second largest party, with the Colombian Liberal Party being the largest.[262]

North America

Canada

| This article is part of a series on |

| Conservatism in Canada |

|---|

|

Canada's conservatives had their roots in the Tory

The conservatives combined

The conservative and autonomist Union Nationale, led by Maurice Duplessis, governed the province of Quebec in periods from 1936 to 1960 and in a close alliance with the Catholic Church, small rural elites, farmers, and business elites. This period, known by liberals as the Great Darkness, ended with the Quiet Revolution and the party went into terminal decline.[267]

By the end of the 1960s, the political debate in Quebec centered around the question of independence, opposing the social democratic and sovereignist Parti Québécois and the centrist and federalist Quebec Liberal Party, therefore marginalizing the conservative movement. Most French Canadian conservatives rallied either the Quebec Liberal Party or the Parti Québécois, while some of them still tried to offer an autonomist third-way with what was left of the Union Nationale or the more populists Ralliement créditiste du Québec and Parti national populaire, but by the 1981 provincial election politically organized conservatism had been obliterated in Quebec. It slowly started to revive at the 1994 provincial election with the Action démocratique du Québec, who served as Official opposition in the National Assembly from 2007 to 2008, before merging in 2012 with François Legault's Coalition Avenir Québec, which took power in 2018. The modern Conservative Party of Canada has rebranded conservatism and, under the leadership of Stephen Harper, added more conservative policies.

Yoram Hazony, a scholar on the history and ideology of conservatism, identified Canadian psychologist Jordan Peterson as the most significant conservative thinker to appear in the English-speaking world in a generation.[268]

United States

| This article is part of a series on |

| Conservatism in the United States |

|---|

|

The meaning of conservatism in the United States is different from the way the word is used elsewhere. As historian Leo P. Ribuffo notes, "what Americans now call conservatism much of the world calls liberalism or neoliberalism".[67] However, the prominent American conservative writer Russell Kirk, in his influential work The Conservative Mind (1953), argued that conservatism had been brought to the United States and he interpreted the American Revolution as a "conservative revolution" against royalist innovation.[269]

American conservatism is a broad system of political beliefs in the United States, which is characterized by respect for American traditions, support for Judeo-Christian values, economic liberalism, anti-communism, and a defense of Western culture. Liberty within the bounds of conformity to conservatism is a core value, with a particular emphasis on strengthening the free market, limiting the size and scope of government, and opposing high taxes as well as government or labor union encroachment on the entrepreneur.

The 1830s

The post-Civil War

In late 19th century, the

The major conservative party in the United States today is the Republican Party, also known as the GOP (Grand Old Party). Modern American conservatives often consider

The conservative movement of the 1950s attempted to bring together the divergent conservative strands, stressing the need for unity to prevent the spread of "godless communism", which Reagan later labeled an "

In the United States,

The Tea Party movement, founded in 2009, proved a large outlet for populist American conservative ideas. Their stated goals included rigorous adherence to the US constitution, lower taxes, and opposition to a growing role for the federal government in health care. Electorally, it was considered a key force in Republicans reclaiming control of the US House of Representatives in 2010.[290][291]

Oceania

Australia

| This article is part of a series on |

| Conservatism in Australia |

|---|

|

The Liberal Party of Australia adheres to the principles of social conservatism and liberal conservatism.[292] It is liberal in the sense of economics. Commentators explain: "In America, 'liberal' means left-of-center, and it is a pejorative term when used by conservatives in adversarial political debate. In Australia, of course, the conservatives are in the Liberal Party."[293] The National Right is the most organised and reactionary of the three faction within the party.[294]

Other conservative parties are the

The largest party in the country is the

Political scientist James Jupp writes that "[the] decline in English influences on Australian reformism and radicalism, and appropriation of the symbols of Empire by conservatives continued under the Liberal Party leadership of Sir Robert Menzies, which lasted until 1966".[295]

New Zealand

| This article is part of a series on |

| Conservatism in New Zealand |

|---|

|

Historic conservatism in New Zealand traces its roots to the unorganised conservative opposition to the New Zealand Liberal Party in the late 19th century. In 1909 this ideological strand found a more organised expression in the Reform Party, a forerunner to the contemporary New Zealand National Party, which absorbed historic conservative elements.[296] The National Party, established in 1936, embodies a spectrum of tendencies, including conservative and liberal. Throughout its history, the party has oscillated between periods of conservative emphasis and liberal reform. Its stated values include "individual freedom and choice" and "limited government".[297]

In the 1980s and 1990s both the National Party and its main opposing party, the traditionally left-wing Labour Party, implemented free-market reforms.[298]

The New Zealand First party, which split from the National Party in 1993, espouses nationalist and conservative principles.[299]

Psychology

Conscientiousness

Disgust sensitivity

A number of studies have found that

Research in the field of

The higher one's disgust sensitivity is, the greater the tendency to make more conservative moral judgments. Disgust sensitivity is associated with moral hypervigilance, which means that people who have higher disgust sensitivity are more likely to think that suspects of a crime are guilty. They also tend to view them as evil, if found guilty, and endorse harsher punishment in the setting of a court.[311]

Authoritarianism

The

A study done on Israeli and Palestinian students in Israel found that RWA scores of right-wing party supporters were significantly higher than those of left-wing party supporters.[314] However, a 2005 study by H. Michael Crowson and colleagues suggested a moderate gap between RWA and other conservative positions, stating that their "results indicated that conservatism is not synonymous with RWA".[315]

According to political scientist Karen Stenner, who specializes in authoritarianism, conservatives will embrace diversity and civil liberties to the extent that they are institutionalized traditions in the social order, but they tend to be drawn to authoritarianism when public opinion is fractious and there is a loss of confidence in public institutions.[316]

Ambiguity intolerance

In 1973, British psychologist

Social dominance orientation

However, David J. Schneider argued for a more complex relationships between the three factors, writing that "correlations between prejudice and political conservatism are reduced virtually to zero when controls for SDO are instituted, suggesting that the conservatism–prejudice link is caused by SDO".[322] Conservative political theorist Kenneth Minogue criticized Pratto's work, saying:

It is characteristic of the conservative temperament to value established identities, to praise habit and to respect prejudice, not because it is irrational, but because such things anchor the darting impulses of human beings in solidities of custom which we do not often begin to value until we are already losing them. Radicalism often generates youth movements, while conservatism is a condition found among the mature, who have discovered what it is in life they most value.[323]

A 1996 study by Pratto and her colleagues examined the topic of racism. Contrary to what these theorists predicted, correlations between conservatism and racism were strongest among the most educated individuals, and weakest among the least educated. They also found that the correlation between racism and conservatism could be accounted for by their mutual relationship with SDO.[324]

Happiness

In his book Gross National Happiness (2008), Arthur C. Brooks presents the finding that conservatives are roughly twice as happy as social liberals.[325] A 2008 study suggested that conservatives tend to be happier than social liberals because of their tendency to justify the current state of affairs and to remain unbothered by inequalities in society.[326] A 2012 study disputed this, demonstrating that conservatives expressed greater personal agency (e.g., personal control, responsibility), more positive outlook (e.g., optimism, self-worth), and more transcendent moral beliefs (e.g., greater religiosity, greater moral clarity).[327]

Prominent statesmen

Prominent intellectuals

See also

National variants

- Conservatism in Australia

- Conservatism in Bangladesh

- Conservatism in Brazil

- Conservatism in Canada

- Conservatism in Colombia

- Conservatism in Germany

- Conservatism in Hong Kong

- Conservatism in India

- Conservatism in Japan

- Conservatism in Malaysia

- Conservatism in New Zealand

- Conservatism in Pakistan

- Conservatism in Peru

- Conservatism in Russia

- Conservatism in Serbia

- Conservatism in South Korea

- Conservatism in Taiwan

- Conservatism in Turkey

- Conservatism in the United Kingdom

- Conservatism in the United States

Ideological variants

- Authoritarian conservatism

- Black conservatism

- Corporatist conservatism

- Cultural conservatism

- Feminist conservatism

- Fiscal conservatism

- Green conservatism

- LGBT conservatism

- Liberal conservatism

- Libertarian conservatism

- Moderate conservatism

- National conservatism

- Neoconservatism

- Paternalistic conservatism

- Pragmatic conservatism

- Progressive conservatism

- Populist conservatism

- Social conservatism

- Traditionalist conservatism

- Ultraconservatism

Related topics

References

- ^ a b Hamilton, Andrew (2019). "Conservatism". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- ^ Encyclopædia Britannica: "Conservatism, political doctrine that emphasizes the value of traditional institutions and practices."

- ^ Heywood 2004, pp. 166–167: "In particular, conservatives have emphasized that society is held together by the maintenance of traditional institutions such as the family and by respect for an established culture, based upon religion, tradition and custom."

- ^ ISBN 978-1-86189-812-8.

It is clear that conservatives are influenced not only by their ideology, but also by the political context – no surprise there – but contexts vary and so, therefore, do conservatives.

- ^ Giubilei 2019, p. 37: "Conservatives aim to conserve the natural and fundamental elements of society, which are: private property, family, the homeland, and even religion […] the right-wing conservative is such not because he wants to conserve any regime and any institutions, but rather specific institutions and particular values."

- ^ a b c d e Encyclopædia Britannica.

- ^ Fawcett 2020, pp. 3–18.

- ^ a b Muller 1997, p. 26.

- ^ Heywood 2012, p. 66.

- ISBN 978-1-4443-1105-1.

- ^ Heywood 2017, p. 74: "While contemporary conservatives are keen to demonstrate their commitment to democratic, particularly liberal-democratic, principles, there is a tradition within conservatism that has favoured authoritarian rule, especially in continental Europe."

- ISBN 1594200203.are populists who believe that pointy-headed intellectuals need to be given a good ducking

Americans who describe themselves as 'conservatives' nevertheless disagree on almost all the most fundamental questions of life. […] The Straussians at the Weekly Standard are philosophical elitists who believe that the masses need to be steered by an educated intelligentsia. The antitax crusaders who march behind Grover Norquist

- ^ Heywood 2017, p. 63: "The Canadian Conservative Party adopted the title Progressive Conservative precisely to distance itself from reactionary ideas."

- ^ Fawcett 2020, p. 59: "Conservatives can be radical or moderate. It depends on the state of the contest, on the stakes in the contest, and on which party is attacking, which defending."

- ISBN 978-0-7099-2766-2.

- ^ Hogg Baron Hailsham of St. Marylebone, Quintin (1959). The Conservative Case. Penguin Books.

- ^ Encyclopedia Britannica, https://www.britannica.com/topic/conservatism/Intellectual-roots-of-conservatism

- ^ Heywood 2004, p. 346.

- ^ a b Heywood 2017, p. 66.

- ^ Robin, Corey (January 8, 2012). "The Conservative Reaction". The Chronicle of Higher Education. Retrieved December 23, 2016.

- .

- ^ Farrell, Henry (February 1, 2018). "Trump is a typical conservative". The Washington Post. Retrieved August 29, 2023.

- ISBN 9781800752344.

- ^ Gómez Dávila, Nicolás (2004) [1977]. "Escolios a un Texto Implicito". Archived from the original on November 17, 2006.

- ^ "hierarchy". Online Etymology Dictionary.

- ^ Heywood 2017, p. 67.

- ^ Fawcett 2020, p. 48.

- ^ Giubilei 2019, pp. 18–19.

- ISBN 978-0-415-67046-3.

- ISBN 9781903386576.

- ^ Weber, Max (1922). Economy and Society. p. 215.

- ISBN 978-0-520-03194-4.

- ^ Kojève 2020, pp. 14–28.

- ISBN 978-1-56000-667-1.

- ^ Kojève 2020, p. xvii.

- ^ Arendt, Hannah (1954). Between Past and Future: Six Exercises in Political Thought. Viking Press. pp. 91–92.

- ^ Kojève 2020, pp. xviii–xix.

- ISBN 978-0-00-255871-6.

- ^ "reactionary". Merriam-Webster. May 9, 2023.

- ^ McLean & McMillan 2009.

- ISBN 978-0190692001.

This book is about the second half of the story, the demarche, and the political ideas –– variously called conservative, reactionary, revanchist, counterrevolutionary –– that grow out of and give rise to it.

- ISBN 978-1590179024.

Reactionaries are not conservatives. This is the first thing to be understood about them. They are, in their way, just as radical as revolutionaries and just as firmly in the grip of historical imaginings.

- ISBN 978-1412842341.

- ^ a b Siegfried, Heit; Johnston, Otto W. (1980). "German Romanticism: An Ideological Response to Napoleon". Consortium on Revolutionary Europe 1750–1850: Proceedings. Vol. 9. pp. 187–197.

- ^ King, Peter (2012). Reaction: Against the Modern World. Andrews UK Limited.

- .

- ^ Campbell, Francis Stuart. "Credo of a Reactionary". The American Mercury.

- ISBN 9781890318123.

- ^ Eccleshall 1990, pp. ix, 21

- JSTOR 1951007.

- ISBN 978-0-333-96178-0.

- ^ Lock, F. P. (2006). Edmund Burke. Volume II: 1784–1797. Clarendon Press. p. 585.

- ^ Stanlis, Peter J. (2009). Edmund Burke: Selected Writings and Speeches. Transaction Publishers. p. 18.

- ^ Auerbach 1959, p. 33.

- ISBN 9783843375436.

- ^ Auerbach 1959, pp. 37–40.

- ^ Auerbach 1959, pp. 52–54.

- ^ Auerbach 1959, p. 41.

- ^ Adams, Ian (2002). Political Ideology Today (2 ed.). Manchester University Press. p. 46.

- ^ Fawcett 2020, p. 20.

- ^ Fawcett 2020, pp. 25–30.

- ^ Fawcett 2020, pp. 5–7.

- ISBN 978-0-495-50112-1.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-8264-6155-1.

- ^ Giubilei 2019, p. 21.

- ISBN 9781351526487.

- ^ .

- ISBN 978-0-7506-9897-9.

- ISBN 978-81-7625-784-8.

- ISBN 978-0-571-26533-6.

- ISBN 978-0199585977.

- ^ "Parties and Elections Resources and Information". www.parties-and-elections.de.

- ^ Traynor, Ian (April 4, 2006). "The EU's weary travellers". The Guardian. Archived from the original on April 7, 2006.

- ^ "In Defense of Nations". National Review. September 13, 2018. Archived from the original on June 22, 2022. Retrieved October 29, 2018.

- ^ Frohnen 2006, pp. 870–875.

- ^ Cram, Ralph Adams (1936). "Invitation to Monarchy".

- ^ Lind, William S. (2006). "The Prussian Monarchy Stuff". LewRockwell.com. Center for Libertarian Studies.

- ^ Leslie Wayne (January 6, 2018). "What's the Cure for Ailing Nations? More Kings and Queens, Monarchists Say". The New York Times.

- ISBN 978-0-472-10645-5.

- ^ Heywood 2017, p. 69.

- ^ The Next Digital Divide Archived June 6, 2011, at the Wayback Machine (utne article)

- ^ "The World & I". The World & I. Vol. 1, no. 5. Washington Times Corp. 1986. Retrieved August 19, 2011.

militant atheism was incompatible with conservatism

- ISBN 978-0-415-21494-0.

In addition, conservative Christians often endorsed far-right regimes as the lesser of two evils, especially when confronted with militant atheism in the USSR.

- ISBN 978-0-7546-6011-8. Retrieved August 19, 2011.

If anything the reverse is true: moral conservatives continue to oppose secular liberals on a wide range of issues.

- ISBN 978-0-534-61716-5

- ^ "So Christians do not approve of the taking of illegal drugs, including most recreational drugs, especially those which can alter the mind and make people incapable of praying or being alert to God". Archived from the original on October 20, 2017.

- ^ Petersen, David L. (2005). "Genesis and Family Values". Journal of Biblical Literature. 124 (1).

- ISBN 978-1-137-27244-7.

- ^ Heywood 2012, p. 80.

- ^ Dunleavy, Patrick; et al. (2000). British Political Science: Fifty Years of Political Studies. Wiley-Blackwell. pp. 107–108.

- ^ Robert Blake (1967). Disraeli (2 ed.). Eyre & Spottiswoode. p. 524.

- ^ Russel, Trevor (1978). The Tory Party: Its Policies, Divisions and Future. Penguin. p. 167.

- ^ John Alden Nichols. Germany after Bismarck, the Caprivi era, 1890–1894: Issue 5. Harvard University Press, 1958. p. 260

- ^ a b Jonathan Lurie. William Howard Taft: The Travails of a Progressive Conservative. New York, New York, US: Cambridge University Press, 2012. p.196

- ISBN 9780807119426.

- ^ a b Hugh Segal. The Right Balance. Victoria, British Columbia, Canada: Douglas & McIntyre, 2011. pp. 113–148

- ISBN 978-0-7190-2354-5.

- ^ Lewis, David. Illusions of Grandeur: Mosley, Fascism, and British Society, 1931-81. Manchester University Press. p. 218.

- ISBN 978-0-19-958597-7.

- ^ Michael H. Kater. Never Sang for Hitler: The Life and Times of Lotte Lehmann, 1888–1976. Cambridge University Press, 2008. p. 167

- ^ ISBN 9637326235.

- ISBN 978-0714682624.

- ^ Howard J. Wiarda, Margaret MacLeish Mott. Catholic Roots and Democratic Flowers: Political Systems in Spain and Portugal. Westport, CT: Greenwood Publishing Group, 2001. p. 49

- ^ Bischof 2003, p. 26.

- ^ Stanley G. Payne. Fascism in Spain, 1923–1977. Madison: Wisconsin University Press, 1999. pp. 77–102.

- ^ Blinkhorn 1990, p. 10.

- ^ Cyprian Blamires. World Fascism: A Historical Encyclopedia, Volume 1. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO, 2006. p. 21

- ISBN 978-0-8047-3615-2.

- ^ Butnaru, Ion C., The Silent Holocaust: Romania and Its Jews (1992), Praeger/Greenwood: Westport, pp. 62–63

- ^ a b Balfour, Michael (1964). The Kaiser and his Times. Houghton Mifflin. p. 409.

- ^ "The Kaiser on Hitler" (PDF). Ken. December 15, 1938. Retrieved December 23, 2023.

- ^ Seymour M. Lipset, "Social Stratification and 'Right-Wing Extremism'" British Journal of Sociology 10#4 (1959), pp. 346–382 on-line Archived April 22, 2022, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Fawcett 2020, p. 263.

- ^ Remmer 1989, p. 10.

- ^ Remmer 1989, pp. 5–6.

- ISBN 9781847926418.

- ^ Ware 1996, pp. 31–33.

- ^ "Right wing politics in India, by Archana Venkatesh". osu.edu. October 1, 2019. Retrieved March 14, 2024.

- ISBN 978-9353450625.

- ^ "BJP v CCP: The rise of the world's biggest political party". Sydney Morning Herald. October 16, 2022. Archived from the original on July 1, 2023. Retrieved July 1, 2023.

- ^ "How BJP became world's largest political party in 4 decades". The Times of India. April 16, 2022. Archived from the original on June 28, 2023. Retrieved July 1, 2023.

- ^ "Narendra Modi's Message to America". National Review. June 23, 2022. Archived from the original on July 1, 2023. Retrieved July 1, 2023.

His Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP, or "Indian People's Party") is on the right of the Indian political spectrum. It is the largest political party in the world, with more members than the Chinese Communist Party, and supports Hindu nationalist ideology and economic development.

- ISBN 978-81-250-1434-8.

BJP propounds and extends the ideology of cultural nationalism.

- ISBN 9781400871414.

- ^ Heywood 2017, pp. 63–64.

- ^ "Japan as a One-Party State: The Future for Koizumi and Beyond | Wilson Center". web.archive.org. February 15, 2021. Retrieved April 19, 2024.

- ^ "Asian Military Strength (2024)". www.globalfirepower.com. Retrieved April 19, 2024.

- ^ "5 Things to know about Japan's emperor and imperial family". The Seattle Times. August 8, 2016. Retrieved April 19, 2024.

- ^ Todd, Emmanuel (1985). The Explanation of Ideology: Family Structures and Social Systems. Blackwell.

- ^ "Overview of the Public Opinion Survey on Diplomacy (page 4)" (PDF). Public Relations Office, Government of Japan. December 2017. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 1, 2021.

- ISBN 0393041565.

- .

- .

- ISBN 978-0674984424.

- ^ "Abe's reshuffle promotes right-wingers". koreajoongangdaily.joins.com. September 4, 2014. Retrieved April 19, 2024.

- ^ "The Western World". WorldAtlas. April 26, 2021.

- ISBN 981-210-408-9.

- ISBN 978-0-674-06106-4.

- ^ Blinkhorn 1990, p. 7.

- ^ Gordon Craig, "The System of Alliances and the Balance of Power." in J.P.T. Bury, ed., The New Cambridge Modern History, Vol. 10: The Zenith of European Power, 1830–70 (1960), p. 266.

- ^ von Kuehnelt-Leddihn 1943, pp. 139–140.

- ISBN 0-00-638255-X.

- – via Taylor & Francis Online.

- ^ Congdon, Lee (March 26, 2012). "Kuehnelt-Leddihn and American Conservatism". Crisis Magazine. Retrieved December 23, 2023.

- ISBN 9781351315203.

- ^ Bischof 2003.

- ^ von Kuehnelt-Leddihn 1943, p. 210.

- ISBN 0-521-31625-1.

- ^ "Sebastian Kurz, der "junge Metternich"". kurier.at (in German). January 16, 2014. Archived from the original on May 18, 2021. Retrieved December 15, 2023.

- ^ Annesley 2005, p. 124.

- ^ Zig Layton-Henry, ed. Conservative Politics in Western Europe (St. Martin's Press, 1982)

- ^ Paul Lucardie and Hans-Martien Ten Napel, "Between confessionalism and liberal conservatism: the Christian Democratic parties of Belgium and the Netherlands Archived June 23, 2020, at the Wayback Machine." in David Hanley, ed. Christian Democracy in Europe: A Comparative Perspective (London: Pinter 1994) pp. 51–70

- ^ Philippe Siuberski (October 7, 2014). "Belgium gets new government with Michel as PM". Yahoo News. AFP. Retrieved November 7, 2014.

- ^ a b Skov, Christian Egander. "Konservatisme". danmarkshistorien.dk (in Danish). Retrieved July 17, 2023.

- ^ euconedit (September 17, 2023). "Nordic Conservative Homecoming". europeanconservative.com. Retrieved December 3, 2023.

- ^ Annesley 2005, p. 68.

- ^ Kosiara-Pedersen, Karina (July 10, 2023). "Det Konservative Folkeparti". Den Store Danske (in Danish). Retrieved July 17, 2023.

- ^ Abildlund, Andreas (October 9, 2015). "Den konservative højrefløj er gået i udbrud". Information (in Danish).

- ^ Critique – Idédebat og kulturkamp, December 2, 2010: "Konservatismen og kongedømmet" Archived March 19, 2022, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Berlingske, July 8, 2014: "Kongehuset bringer danskerne sammen" Archived March 18, 2022, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Siaroff 2000, p. 243.

- ^ Helsingin Sanomat, October 11, 2004, International poll: Anti-Russian sentiment runs very strong in Finland. Only Kosovo has more negative attitude

- ISBN 9780873385589.

- ISBN 978-90-04-28071-7.

- ^ https://mannerheim.fi/pkaskyt/pk49_18.gif

- ISBN 9781524762933.

- ISBN 9780714615295.

- ^ Fawcett 2020, pp. 20–21.

- ISBN 978-0-521-84480-2.

- ISBN 978-1-85109-439-4.

- ^ Maurice Larkin, Religion, politics and preferment in France since 1890: La Belle Epoque and its legacy (Cambridge University Press, 2002)

- ^ Stanley Hoffmann, "The Vichy Circle of French Conservatives" in Hoffmann, Decline or Renewal? France since 1930s (1974) pp. 3–25

- ISBN 978-0-7658-0576-8.

- ^ Richard Vinen, "The Parti républicain de la Liberté and the Reconstruction of French Conservatism, 1944–1951", French History (1993) 7#2 pp. 183–204

- ^ Ware 1996, p. 32.

- ISBN 978-0-495-50109-1.

- ^ "Eric Zemmour: Meet the right-wing TV pundit set to shake up France's presidential race". euronews.com. October 13, 2021. Retrieved October 30, 2021.

- JSTOR 27707117.

- OCLC 1166587654. Retrieved August 29, 2023.

- ^ Eyck, Erich (1964). Bismarck and the German Empire. pp. 58–68.

- ISBN 978-0-19-978252-9.

- ISBN 978-1-107-65247-7.

- ISBN 978-0-8014-4075-5.

- JSTOR 1432746.

- ISBN 978-0520026261.

- ISBN 0-333-65014-X.

- ^ Ringer, Fritz K. (1990). The Decline of the German Mandarins: The German Academic Community, 1890–1933. University Press of New England. p. 201.

- ISBN 0671624202.

- ISBN 0-415-16493-1.

- ISBN 978-1-84844-222-1.

- ^ "The Maturing of a Humane Economist Modern Age". March 23, 2007. Archived from the original on March 23, 2007. Retrieved July 11, 2021.

- ^ Michael John Williams (February 12, 2020). "The German Center Does Not Hold". New Atlanticist. Archived from the original on June 20, 2020. Retrieved March 7, 2020.

- ^ "Germany bewildered about how to halt the rise of the AfD". POLITICO. October 3, 2023. Retrieved March 14, 2024.

- ISBN 978-0-8447-3434-7pp. 49–59

- ^ "Ανεξάρτητοι Έλληνες – 404 error". anexartitoiellines.gr. Archived from the original on August 4, 2020. Retrieved August 30, 2020.

- ^ Deák, István (1963). "Hungary". In Roger, Hans (ed.). The European Right: A Historical Profile. p. 364.

- ISBN 978-0-87586-138-8, pp. 107–108

- ISBN 978-8815127051.

- ^ De Grand, Alexander (2000). Italian Fascism: its Origins and Development (3rd ed.). University of Nebraska Press. p. 145.

- ^ Sternhill, Zeev (1998). "Fascism". In Griffin, Roger (ed.). International Fascism: Theories, Causes, and the New Consensus. London, England; New York: Arnold Publishers. p. 32.

- ^ Fella, Stefano; Ruzza, Carlo (2009). Re-inventing the Italian Right: Territorial Politics, Populism and 'Post-Fascism'. Routledge.