Constantinian shift

Constantinian shift is used by some

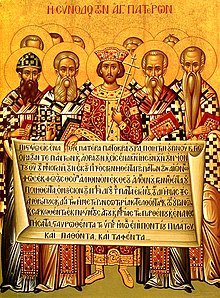

The Shift

During the 4th century, however, there was no real unity between church and state: in the course of the

Towards the end of the century, Bishop

Theological implications

| Separation of church and state in the history of the Catholic Church |

|---|

Critics of state-aligned Christianity often point to the ascension of Constantine as the beginning of Caesaropapism: according to this critique, the official Christianity of the Roman state rapidly became a religious and metaphysical justification for the existence, exercise, and expansion of worldly political power, ultimately facilitating earthly Christian empire both for Rome and its successors across Christendom. Similar criticisms are levied by Christian anarchists, who claim that the Constantinian shift triggered the Great Apostasy by transforming the religion into a means for preserving the ruling elite's power and justifying violence.[9]

Theologians critical of the Constantinian shift also see it as the point at which membership in the Christian church became associated with a social concept of citizenship, rather than reflecting one's internal decisions and feelings. American theologian Stanley Hauerwas notes the shift as forming part of the foundation for the contemporary American conception of Christianity, one that is closely associated with patriotism and civil religion.[citation needed]

See also

- Antichrist

- Constantinianism

- Christianity in the Roman Empire

- Divine right of kings

- Donation of Constantine

- Erastianism

- Great Apostasy

- Historicism (Christianity)

- Persecution of pagans in the late Roman Empire

- Sacralism

References

- ^ Clapp, Rodney (1996). A Peculiar People. InterVarsity Press. p. 23.

What might be called the Constantinian shift began around the year 200 and took more than two hundred years to grow and unfold to full bloom.

- ^ e.g. in Yoder, John H. (1996). "Is There Such a Thing as Being Ready for Another Millennium?". In Miroslav Volf; Carmen Krieg; Thomas Kucharz (eds.). The Future of Theology: Essays in Honor of Jurgen Moltmann. Eerdmanns. p. 65.

The most impressive transitory change underlying our common experience, one that some thought was a permanent lunge forward in salvation history, was the so-called Constantinian shift.

- Defending Constantine: The Twilight of an Empire and the Dawn of Christendom, p 287.

- ^ Lactantius XLIV, 5

- ^ Eusebius XXVII–XXXII

- ^ Brown 2006, 60.

- ^ Theodosian Code, XVI.1.2

- ISBN 978-1-60206516-1. Retrieved 2012-12-16.

374[:] Gregory is exiled under Valens

- Lexington Books. pp. 149–168.

- ^ "The Donatists and Their Relation to Church and State « Biographia Evangelica". Archived from the original on 2019-12-27. Retrieved 2019-06-04.

- ^ Olson, 172

- ^ Barnes, 230.

Further reading

- Timothy Barnes, Constantine and Eusebius, 1981

- Theodosian Code, Henry Bettenson, ed., Documents of the Christian Church, (London: Oxford University Press, 1943), p. 31. see: http://www.fordham.edu/halsall/source/theodcodeXVI.html Archived 2007-02-27 at the Wayback Machine

- Peter Brown, The Rise of Western Christendom (Oxford: Blackwell Publishing, 2003),60.

- James Bulloch, From Pilate to Constantine, 1981

- Eusebius of Caesarea, Life of Constantine, Library of Nicene and Post Nicene Fathers, 2nd series (New York: Christian Literature Co., 1990), Vol I, 489–91. see: http://www.fordham.edu/halsall/source/conv-const.html

- Alistair Kee, Constantine Versus Christ, 1982

- Lactantius, Lucius Caecilius Firmianus, On the manner in which the persecutors died (English translation of De Mortibus Persecutorum) see: http://www.intratext.com/IXT/ENG0296/_P18.HTM

- Ramsay MacMullen, Christianising the Roman Empire, 1984

- Roger E. Olson, The Story of Christian Theology, 1999

External links

- Social Constantinianism - an Evangelical perspective on the Constantinian shift

- Basil's Struggle with Arianism after Constantine.

- Timeline of Fourth-Century Roman Imperial Laws showing the Constantinian shift