Copper in biology

Daily dietary standards for copper have been set by various health agencies around the world. Standards adopted by some nations recommend different copper intake levels for adults, pregnant women, infants, and children, corresponding to the varying need for copper during different stages of life.

Biochemistry

- Cu+-SOD + O2− + 2H+ → Cu2+-SOD + H2O2 (oxidation of copper; reduction of superoxide)

- Cu2+-SOD + O2− → Cu+-SOD + O2 (reduction of copper; oxidation of superoxide)

The protein

A unique tetranuclear copper center has been found in nitrous-oxide reductase.[5]

Chemical compounds which were developed for treatment of Wilson's disease have been investigated for use in cancer therapy.[6]

Optimal copper levels

Researchers specializing in the fields of

Essentiality

Copper is an essential trace element (i.e., micronutrient) that is required for plant, animal, and human health.[7] It is also required for the normal functioning of

Copper's essentiality was first discovered in 1928, when it was demonstrated that rats fed a copper-deficient milk diet were unable to produce sufficient red blood cells.[9] The anemia was corrected by the addition of copper-containing ash from vegetable or animal sources.

Fetuses, infants, and children

Since copper availability in the body is hindered by an excess of iron and zinc intake, pregnant women prescribed iron supplements to treat anemia or zinc supplements to treat colds should consult physicians to be sure that the prenatal supplements they may be taking also have nutritionally-significant amounts of copper.

When newborn babies are breastfed, the babies' livers and the mothers' breast milk provide sufficient quantities of copper for the first 4–6 months of life. When babies are weaned, a balanced diet should provide adequate sources of copper.

Cow's milk and some older infant formulas are depleted in copper. Most formulas are now fortified with copper to prevent depletion.

Most well-nourished children have adequate intakes of copper. Health-compromised children, including those who are premature,

Homeostasis

Copper is absorbed, transported, distributed, stored, and excreted in the body according to complex

Many aspects of copper

| Enzymes | Function |

|---|---|

| Amine oxidases | Group of enzymes oxidizing primary amines (e.g., tyramine, histidine and polylamines)

|

| Ceruloplasmin (ferroxidase I) | Multi-copper oxidase in plasma, essential for iron transport |

| Cytochrome c oxidase | Terminal oxidase enzyme in mitochondrial respiratory chain, involved in electron transport |

| Dopamine beta-hydroxylase | Involved in catecholamine metabolism, catalyzes conversion of dopamine to norepinephrine |

| Hephaestin | Multi-copper portal circulation

|

| Lysyl oxidase | Cross-linking of collagen and elastin |

| Peptidylglycine alpha-amidating mono-oxygenase (PAM) | Multifunction enzyme involved in maturation and modification of key peptides )

|

| Superoxide dismutase (Cu, Zn) | extracellular enzyme involved in defense against reactive oxygen species (e.g., destruction of superoxide radicals)

|

| Tyrosinase | Enzyme catalyzing melanin and other pigment production |

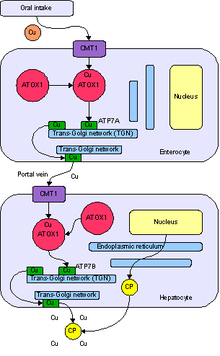

The transport and metabolism of copper in living organisms is currently the subject of much active research. Copper transport at the cellular level involves the movement of extracellular copper across the

Absorption

In mammals copper is absorbed in the stomach and small intestine, although there appear to be differences among species with respect to the site of maximal absorption.[21] Copper is absorbed from the stomach and duodenum in rats[22] and from the lower small intestine in hamsters.[23] The site of maximal copper absorption is not known for humans, but is assumed to be the stomach and upper intestine because of the rapid appearance of 64Cu in the plasma after oral administration.[24]

Absorption of copper ranges from 15 to 97%, depending on copper content, form of the copper, and composition of the diet.[25][26][27][28][29]

Various factors influence copper absorption. For example, copper absorption is enhanced by ingestion of animal

Some forms of copper are not soluble in stomach acids and cannot be absorbed from the stomach or small intestine. Also, some foods may contain indigestible fiber that binds with copper. High intakes of zinc can significantly decrease copper absorption. Extreme intakes of Vitamin C or iron can also affect copper absorption, reminding us of the fact that micronutrients need to be consumed as a balanced mixture. This is one reason why extreme intakes of any one single micronutrient are not advised.[39] Individuals with chronic digestive problems may be unable to absorb sufficient amounts of copper, even though the foods they eat are copper-rich.

Several copper transporters have been identified that can move copper across cell membranes.[40][41] Other intestinal copper transporters may exist. Intestinal copper uptake may be catalyzed by Ctr1. Ctr1 is expressed in all cell types so far investigated, including enterocytes, and it catalyzes the transport of Cu+1 across the cell membrane.[42]

Excess copper (as well as other heavy metal ions like zinc or cadmium) may be bound by metallothionein and sequestered within intracellular vesicles of

Distribution

Copper released from intestinal cells moves to the

Excretion

Bile is the major pathway for the excretion of copper and is vitally important in the control of liver copper levels.[47][48][49] Most fecal copper results from biliary excretion; the remainder is derived from unabsorbed copper and copper from desquamated mucosal cells.

| Dose range | Approximate daily intakes | Health outcomes |

|---|---|---|

| Death | ||

| Gross dysfunction and disturbance of metabolism of other nutrients; hepatic

"detoxification" and homeostasis overwhelmed | ||

| Toxic | >5.0 mg/kg body weight | Gastrointestinal metallothionein induced (possible differing effects of acute and chronic

exposure) |

| 100 μg/kg body weight | Plateau of absorption maintained; homeostatic mechanisms regulate absorption of copper | |

| Adequate | 34 μg/kg body weight | Hepatic uptake, sequestration and excretion effect homeostasis; glutathione-dependent uptake of copper; binding to metallothionein; and lysosomal excretion of copper |

| 11 μg/kg body weight | Biliary excretion and gastrointestinal uptake normal | |

| 9 μg/kg body weight | Hepatic deposit(s) reduced; conservation of endogenous copper; gastrointestinal

absorption increased | |

| Deficient | 8.5 μg/kg body weight | Negative copper balance |

| 5.2 μg/kg body weight | Functional defects, such as lysyl oxidase and superoxide dismutase activities reduced; impaired substrate metabolism | |

| 2 μg/kg body weight | Peripheral pools disrupted; gross dysfunction and disturbance of metabolism of other

nutrients; death |

Dietary recommendations

Various national and international organizations concerned with nutrition and health have standards for copper intake at levels judged to be adequate for maintaining good health. These standards are periodically changed and updated as new scientific data become available. The standards sometimes differ among countries and organizations.

Adults

The

Adolescents, children, and infants

Full-term and premature infants are more sensitive to copper deficiency than adults. Since the fetus accumulates copper during the last 3 months of pregnancy, infants that are born prematurely have not had sufficient time to store adequate reserves of copper in their livers and therefore require more copper at birth than full-term infants.[citation needed]

For full-term infants, the North American recommended safe and adequate intake is approximately 0.2 mg/day. For premature babies, it is considerably higher: 1 mg/day. The World Health Organization has recommended similar minimum adequate intakes and advises that premature infants be given formula supplemented with extra copper to prevent the development of copper deficiency.[39]

Pregnant and lactating women

In North America, the IOM has set the RDA for pregnancy at 1.0 mg/day and for lactation at 1.3 mg/day.[53] The European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) refers to the collective set of information as Dietary Reference Values, with Population Reference Intake (PRI) instead of RDA. PRI for pregnancy is 1.6 mg/day, for lactation 1.6 mg/day – higher than the U.S. RDAs.[55]

Food sources

Foods contribute virtually all of the copper consumed by humans.[56][57][58]

In both developed and developing countries, adults, young children, and adolescents who consume diets of grain, millet, tuber, or rice along with legumes (beans) or small amounts of fish or meat, some fruits and vegetables, and some vegetable oil are likely to obtain adequate copper if their total food consumption is adequate in calories. In developed countries where consumption of red meat is high, copper intake may also be adequate.[59]

As a natural element in the Earth's crust, copper exists in most of the world's surface water and groundwater, although the actual concentration of copper in natural waters varies geographically. Drinking water can comprise 20–25% of dietary copper.[60]

In many regions of the world, copper tubing that conveys drinking water can be a source of dietary copper.[61] Copper tube can leach a small amount of copper, particularly in its first year or two of service. Afterwards, a protective surface usually forms on the inside of copper tubes that slows leaching.

In France and some other countries, copper bowls are traditionally used for whipping egg white, as the copper helps stabilise bonds in the white as it is beaten and whipped. Small amounts of copper may leach from the bowl during the process and enter the egg white.[62][63]

Supplementation

Copper supplements can prevent copper deficiency. Copper supplements are not prescription medicines, and are available at vitamin and herb stores and grocery stores and online retailers. Different forms of copper supplementation have different absorption rates. For example, the absorption of copper from

Supplementation is generally not recommended for healthy adults who consume a well-balanced diet which includes a wide range of foods. However, supplementation under the care of a physician may be necessary for premature infants or those with low birth weights, infants fed unfortified formula or cow's milk during the first year of life, and malnourished young children. Physicians may consider copper supplementation for 1) illnesses that reduce digestion (e.g., children with frequent

Many popular vitamin supplements include copper as small inorganic molecules such as cupric oxide. These supplements can result in excess free copper in the brain as the copper can cross the blood-brain barrier directly. Normally, organic copper in food is first processed by the liver which keeps free copper levels under control.[citation needed]

Copper deficiency and excess health conditions (non-genetic)

If insufficient quantities of copper are ingested, copper reserves in the liver will become depleted and a copper deficiency leading to disease or tissue injury (and in extreme cases, death). Toxicity from copper deficiency can be treated with a balanced diet or supplementation under the supervision of a doctor. On the contrary, like all substances, excess copper intake at levels far above World Health Organization limits can become toxic.[64] Acute copper toxicity is generally associated with accidental ingestion. These symptoms abate when the high copper food source is no longer ingested.

In 1996, the International Program on Chemical Safety, a World Health Organization-associated agency, stated "there is greater risk of health effects from deficiency of copper intake than from excess copper intake". This conclusion was confirmed in recent multi-route exposure surveys.[57][65]

The health conditions of non-genetic copper deficiency and copper excess are described below.

Copper deficiency

There are conflicting reports on the extent of deficiency in the U.S. One review indicates approximately 25% of adolescents, adults, and people over 65, do not meet the Recommended Dietary Allowance for copper.[12] Another source states less common: a federal survey of food consumption determined that for women and men over the age of 19, average consumption from foods and beverages was 1.11 and 1.54 mg/day, respectively. For women, 10% consumed less than the Estimated Average Requirement, for men fewer than 3%.[66]

Acquired copper deficiency has recently been implicated in adult-onset progressive myeloneuropathy

Other conditions linked to copper deficiency include osteoporosis,

Populations susceptible to copper deficiency include those with genetic defects for

Copper excess

Copper excess is a subject of much current research. Distinctions have emerged from studies that copper excess factors are different in normal populations versus those with increased susceptibility to adverse effects and those with rare genetic diseases.

Excess copper intake causes stomach upset, nausea, and diarrhea and can lead to tissue injury and disease.

The

While the cause and progression of Alzheimer's disease are not well understood,[citation needed] research indicates that, among several other key observations, iron,[80][81] aluminum,[82] and copper[83][84] accumulate in the brains of Alzheimer's patients. However, it is not yet known whether this accumulation is a cause or a consequence of the disease.

Research has been ongoing over the past two decades to determine whether copper is a causative or a preventive agent of Alzheimer's disease.[

Furthermore, long-term copper treatment (oral intake of 8 mg copper (Cu-(II)-orotate-dihydrate)) was excluded as a risk factor for Alzheimer's disease in a noted clinical trial on humans[90] and a potentially beneficial role of copper in Alzheimer's disease has been demonstrated on cerebral spinal fluid levels of Aβ42, a toxic peptide and biomarker of the disease.[91] More research is needed to understand metal homeostasis disturbances in Alzheimer's disease patients and how to address these disturbances therapeutically. Since this experiment used Cu-(II)-orotate-dihydrate, it does not relate to the effects of cupric oxide in supplements.[92]

Copper toxicity from excess exposures

In humans, the liver is the primary organ of copper-induced toxicity. Other target organs include bone and the central nervous and immune systems.[15] Excess copper intake also induces toxicity indirectly by interacting with other nutrients. For example, excess copper intake produces anemia by interfering with iron transport and/or metabolism.[14][15]

The identification of genetic disorders of copper metabolism leading to severe copper toxicity (i.e.,

Acute exposures

In case reports of humans intentionally or accidentally ingesting high concentrations of copper salts (doses usually not known but reported to be 20–70 grams of copper), a progression of symptoms was observed including abdominal pain, headache, nausea, dizziness, vomiting and diarrhea, tachycardia, respiratory difficulty, hemolytic anemia, hematuria, massive gastrointestinal bleeding, liver and kidney failure, and death.

Episodes of acute gastrointestinal upset following single or repeated ingestion of drinking water containing elevated levels of copper (generally above 3–6 mg/L) are characterized by nausea, vomiting, and stomach irritation. These symptoms resolve when copper in the drinking water source is reduced.

Three experimental studies were conducted that demonstrate a threshold for acute gastrointestinal upset of approximately 4–5 mg/L in healthy adults, although it is not clear from these findings whether symptoms are due to acutely irritant effects of copper and/or to metallic, bitter, salty taste.[94][95][96][97] In an experimental study with healthy adults, the average taste threshold for copper sulfate and chloride in tap water, deionized water, or mineral water was 2.5–3.5 mg/L.[98] This is just below the experimental threshold for acute gastrointestinal upset.

Chronic exposures

The long-term toxicity of copper has not been well studied in humans, but it is infrequent in normal populations that do not have a hereditary defect in copper homeostasis.[99]

There is little evidence to indicate that chronic human exposure to copper results in

No effects of copper supplementation on serum liver enzymes, biomarkers of oxidative stress, and other biochemical endpoints have been observed in healthy young human volunteers given daily doses of 6 to 10 mg/d of copper for up to 12 weeks.[102][103][104][105] Infants aged 3–12 months who consumed water containing 2 mg Cu/L for 9 months did not differ from a concurrent control group in gastrointestinal tract (GIT) symptoms, growth rate, morbidity, serum liver enzyme and bilirubin levels, and other biochemical endpoints.[106]) Serum ceruloplasmin was transiently elevated in the exposed infant group at 9 months and similar to controls at 12 months, suggesting homeostatic adaptation and/or maturation of the homeostatic response.[13]

Dermal exposure has not been associated with systemic toxicity but anecdotal reports of allergic responses may be a sensitization to nickel and cross-reaction with copper or a skin irritation from copper.[15] Workers exposed to high air levels of copper (resulting in an estimated intake of 200 mg Cu/d) developed signs suggesting copper toxicity (e.g., elevated serum copper levels, hepatomegaly). However, other co-occurring exposures to pesticidal agents or in mining and smelting may contribute to these effects.[15] Effects of copper inhalation are being thoroughly investigated by an industry-sponsored program on workplace air and worker safety. This multi-year research effort is expected to be finalized in 2011.[citation needed]

Measurements of elevated copper status

Although a number of indicators are useful in diagnosing copper deficiency, there are no reliable biomarkers of copper excess resulting from dietary intake. The most reliable indicator of excess copper status is liver copper concentration. However, measurement of this endpoint in humans is intrusive and not generally conducted except in cases of suspected copper poisoning. Increased serum copper or ceruolplasmin levels are not reliably associated with copper toxicity as elevations in concentrations can be induced by inflammation, infection, disease, malignancies, pregnancy, and other biological stressors. Levels of copper-containing enzymes, such as cytochrome c oxidase, superoxide dismutase, and diaminase oxidase, vary not only in response to copper state but also in response to a variety of other physiological and biochemical factors and therefore are inconsistent markers of excess copper status.[107]

A new candidate biomarker for copper excess as well as deficiency has emerged in recent years. This potential marker is a chaperone protein, which delivers copper to the antioxidant protein SOD1 (copper, zinc superoxide dismutase). It is called "copper chaperone for SOD1" (CCS), and excellent animal data supports its use as a marker in accessible cells (e.g.,

Hereditary copper metabolic diseases

Several rare genetic diseases (Wilson disease, Menkes disease,

These diseases are inherited and cannot be acquired. Adjusting copper levels in the diet or drinking water will not cure these conditions (although therapies are available to manage symptoms of genetic copper excess disease).

The study of genetic copper metabolism diseases and their associated proteins are enabling scientists to understand how human bodies use copper and why it is important as an essential micronutrient.[citation needed]

The diseases arise from defects in two similar copper pumps, the Menkes and the Wilson Cu-ATPases.[13] The Menkes ATPase is expressed in tissues like skin-building fibroblasts, kidneys, placenta, brain, gut and vascular system, while the Wilson ATPase is expressed mainly in the liver, but also in mammary glands and possibly in other specialized tissues.[15] This knowledge is leading scientists towards possible cures for genetic copper diseases.[64]

Menkes disease

Menkes disease, a genetic condition of copper deficiency, was first described by John Menkes in 1962. It is a rare X-linked disorder that affects approximately 1/200,000 live births, primarily boys.[12] Livers of Menkes disease patients cannot absorb essential copper needed for patients to survive. Death usually occurs in early childhood: most affected individuals die before the age of 10 years, although several patients have survived into their teens and early 20s.[109]

The protein produced by the Menkes gene is responsible for transporting copper across the

Symptoms of the disease include coarse, brittle, depigmented hair and other neonatal problems, including the inability to control body temperature, intellectual disability, skeletal defects, and abnormal connective tissue growth.[citation needed]

Menkes patients exhibit severe neurological abnormalities, apparently due to the lack of several copper-dependent enzymes required for brain development,

With early diagnosis and treatment consisting of daily injections of copper

Ongoing research into Menkes disease is leading to a greater understanding of copper homeostasis,[84] the biochemical mechanisms involved in the disease, and possible ways to treat it.[112] Investigations into the transport of copper across the blood/brain barrier, which are based on studies of genetically altered mice, are designed to help researchers understand the root cause of copper deficiency in Menkes disease. The genetic makeup of transgenic mice is altered in ways that help researchers garner new perspectives about copper deficiency. The research to date has been valuable: genes can be turned off gradually to explore varying degrees of deficiency.[citation needed]

Researchers have also demonstrated in test tubes that damaged DNA in the cells of a Menkes patient can be repaired. In time, the procedures needed to repair damaged genes in the human body may be found.[citation needed]

Wilson's disease

Wilson's disease is produced by mutational defects of a protein that transports copper from the liver to the bile for excretion.[84] The disease involves poor incorporation of copper into ceruloplasmin and impaired biliary copper excretion and is usually induced by mutations impairing the function of the Wilson copper ATPase. These genetic mutations produce copper toxicosis due to excess copper accumulation, predominantly in the liver and brain and, to a lesser extent, in kidneys, eyes, and other organs.[citation needed]

The disease, which affects about 1/30,000 infants of both genders,

Almost always, death occurs if the disease is untreated.[60] Fortunately, identification of the mutations in the Wilson ATPase gene underlying most cases of Wilson's disease has made DNA testing for diagnosis possible.

If diagnosed and treated early enough, patients with Wilson's disease may live long and productive lives.

Over 100 different genetic defects leading to Wilson's disease have been described and are available on the Internet at [1]. Some of the mutations have geographic clustering.[120]

Many Wilson's patients carry different mutations on each chromosome 13 (i.e., they are

It has been suggested that heterozygote carriers of the Wilson's disease gene mutation may be potentially more susceptible to elevated copper intake than the general population.[78] A heterozygotic frequency of 1/90 people has been estimated in the overall population.[15] However, there is no evidence to support this speculation.[13] Further, a review of the data on single-allelic autosomal recessive diseases in humans does not suggest that heterozygote carriers are likely to be adversely affected by their altered genetic status.

Other diseases in which abnormalities in copper metabolism appear to be involved include Indian childhood cirrhosis (ICC), endemic Tyrolean copper toxicosis (ETIC), and idiopathic copper toxicosis (ICT), also known as non-Indian childhood cirrhosis. ICT is a genetic disease recognized in the early twentieth century primarily in the Tyrolean region of Austria and in the Pune region of India.[60]

ICC, ICT, and ETIC are infancy syndromes that are similar in their apparent etiology and presentation.[122] Both appear to have a genetic component and a contribution from elevated copper intake.

In cases of ICC, the elevated copper intake is due to heating and/or storing milk in copper or brass vessels. ICT cases, on the other hand, are due to elevated copper concentrations in water supplies.[15][123] Although exposures to elevated concentrations of copper are commonly found in both diseases, some cases appear to develop in children who are exclusively breastfed or who receive only low levels of copper in water supplies.[123] The currently prevailing hypothesis is that ICT is due to a genetic lesion resulting in impaired copper metabolism combined with high copper intake. This hypothesis was supported by the frequency of occurrence of parental consanguinity in most of these cases, which is absent in areas with elevated copper in drinking water and in which these syndromes do not occur.[123]

ICT appears to be vanishing as a result of greater genetic diversity within the affected populations in conjunction with educational programs to ensure that tinned cooking utensils are used instead of copper pots and pans being directly exposed to cooked foods. The preponderance of cases of early childhood cirrhosis identified in Germany over a period of 10 years were not associated with either external sources of copper or with elevated hepatic metal concentrations[124] Only occasional spontaneous cases of ICT arise today.

Cancer

The role of copper in

The trace element copper had been found promoting tumor growth.[130][131] Several evidence from animal models indicates that tumors concentrate high levels of copper. Meanwhile, extra copper has been found in some human cancers.[132][133] Recently, therapeutic strategies targeting copper in the tumor have been proposed. Upon administration with a specific copper chelator, copper complexes would be formed at a relatively high level in tumors. Copper complexes are often toxic to cells, therefore tumor cells were killed, while normal cells in the whole body remained alive for the lower level of copper.[134] Researchers have also recently found that cuproptosis, a copper-induced mechanism of mitochondrial-related cell death, has been implicated as a breakthrough in the treatment of cancer and has become a new treatment strategy. [135]

Some copper chelators get more effective or novel bioactivity after forming copper-chelator complexes. It was found that Cu2+ was critically needed for PDTC induced apoptosis in HL-60 cells.[136] The copper complex of salicylaldehyde benzoylhydrazone (SBH) derivatives showed increased efficacy of growth inhibition in several cancer cell lines, when compared with the metal-free SBHs.[137][138][139]

SBHs can react with many kinds of transition metal cations and thereby forming a number of complexes.

Salicylaldehyde pyrazole hydrazone (SPH) derivatives were found to inhibit the growth of A549 lung carcinoma cells.[142] SPH has identical ligands for Cu2+ as SBH. The Cu-SPH complex was found to induce apoptosis in A549, H322 and H1299 lung cancer cells.[143]

Contraception with copper IUDs

A copper

Plant and animal health

In addition to being an essential nutrient for humans, copper is vital for the health of animals and plants and plays an important role in agriculture.[145]

Plant health

Copper concentrations in soil are not uniform around the world. In many areas, soils have insufficient levels of copper. Soils that are naturally deficient in copper often require copper supplements before agricultural crops, such as cereals, can be grown.[citation needed]

Copper deficiencies in soil can lead to crop failure. Copper deficiency is a major issue in global food production, resulting in losses in yield and reduced quality of output. Nitrogen fertilizers can worsen copper deficiency in agricultural soils.[citation needed]

The world's two most important food crops, rice and wheat, are highly susceptible to copper deficiency. So are several other important foods, including

The most effective strategy to counter copper deficiency is to supplement the soil with copper, usually in the form of copper sulfate. Sewage sludge is also used in some areas to replenish agricultural land with organics and trace metals, including copper.[citation needed]

Animal health

In livestock, cattle and sheep commonly show indications when they are copper deficient. Swayback, a sheep disease associated with copper deficiency, imposes enormous costs on farmers worldwide, particularly in Europe, North America, and many tropical countries. For pigs, copper has been shown to be a growth promoter.[146]

See also

- Dietary mineral

- Essential nutrient

- List of micronutrients

- Micronutrients

- Nutrition

References

- ISSN 1868-0402

- ^ "Fun facts". Horseshoe crab. University of Delaware. Archived from the original on 22 October 2008. Retrieved 13 July 2008.

- ^ ISBN 0-935702-73-3.

- PMID 10821735.

- PMID 25416395.

- )

- ^ PMID 24470097.

- PMID 34773948.

- .

- ^ Water, National Research Council (US) Committee on Copper in Drinking (2000), "Physiological Role of Copper", Copper in Drinking Water, National Academies Press (US), retrieved 2023-07-15

- PMID 23595680.

- ^ S2CID 10622186.

- ^ S2CID 1621978.

- ^ a b c d e Ralph, A., and McArdle, H. J. 2001. Copper metabolism and requirements in the pregnant mother, her fetus, and children. New York: International Copper Association[page needed]

- ^ ISSN 0250-863X. 200.

- ^ PMID 10425169.

- ^ PMID 10940336.

- ^ PMID 11570430.

- PMID 15157936.

- ^ Lewis, Al, 2009, The Hygienic Benefits of Antimicrobial Copper Alloy Surfaces in Healthcare Settings, a compilation of information and data for the International Copper Association Inc., 2009, available from International Copper Association Inc., A1335-XX/09[verification needed][page needed]

- ^ Stern, B.R. et al., 2007, Copper And Human Health: Biochemistry, Genetics, And Strategies for Modeling Dose-Response Relationships, Journal of Toxicology and Environmental Health, Part B, 10:157–222

- PMID 14302118.

- PMID 14298103.

- PMID 14368026.

- PMID 5083937.

- PMID 5083936.

- PMID 2718922.

- PMID 9587136.

- S2CID 25975221.

- ^ World Health Organization. 1998, Guidelines for drinking-water quality. Addendum to Volume 2, 2nd ed. Geneva[page needed]

- PMID 6631551.

- PMID 3885271.

- PMID 3968585.

- ^ a b Lee, D; Schroeder, J; Gordon, DT (January 1984). "The effect of phytic acid on copper bioavailability". Federation Proceedings. 43 (3): 616–20.

- PMID 4038512.

- PMID 12049998.

- ^ PMID 9587151.

- ^ "Metabolic crossroads of iron and copper". Nutrition Reviews. 15 July 2023.

- ^ a b "CopperInfo.com – Good Health with Copper". Archived from the original on October 15, 2010. Retrieved October 20, 2010.[full citation needed][unreliable medical source?]

- PMID 7495787.

- PMID 8755241.

- S2CID 22339713.

- PMID 5412451.

- PMID 1739401.

- PMID 8615367.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of January 2024 (link - PMID 9587137.

- PMID 3885271.

- PMID 2292474.

- PMID 9587136.

- PMID 10383873.

- ^ WHO/FAO/IAEA, (1996), Trace Elements in Human Nutrition and Health. World Health Organization, Geneva)

- ^ MedlinePlus Encyclopedia: Copper in diet

- ^ S2CID 44243659.

- ^ Tolerable Upper Intake Levels For Vitamins And Minerals (PDF), European Food Safety Authority, 2006

- ^ "Overview on Dietary Reference Values for the EU population as derived by the EFSA Panel on Dietetic Products, Nutrition and Allergies" (PDF). 2017.

- S2CID 220429117.

- ^ PMID 17270248.

- ^ World Health Organization. 1998. Copper. Environmental Health Criteria 200. Geneva: IPCS, WHO[page needed]

- ^ Brewer, George J. (15 July 2023). "Copper-2 Ingestion, Plus Increased Meat Eating Leading to Increased Copper Absorption, Are Major Factors Behind the Current Epidemic of Alzheimer's Disease".

- ^ ISBN 978-1-118-42406-3.

- ^ National Research Council (US) Committee on Copper in Drinking Water (15 July 2023). "Copper in Drinking Water".

- ^ McGee, Harold. On Food and Cooking: The Science and Lore of the Kitchen. New York: Scribner, 2004, edited by Vinay.

- S2CID 4372579.

- ^ a b "Quick Facts". Archived from the original on 2010-10-01. Retrieved 2010-10-20.

- S2CID 19274378.

- ^ What We Eat In America, NHANES 2001–2002 Archived 2015-01-06 at the Wayback Machine. Table A14: Copper.

- S2CID 28373986.

- S2CID 29525351.

- PMID 16007901.

- ^ Cordano, A (1978). "Copper deficiency in clinical medicine". In Hambidge, K. M.; Nichols, B. L. (eds.). Zinc and Copper in Clinical Medicine. New York: SP Med. Sci. Books. pp. 119–26.

- ^ PMID 3060166.

- PMID 7007558.

- S2CID 14771415.

- PMID 1290583.

- PMID 3064814.

- PMID 8615369.

- PMID 2821800.

- ^ a b c U.S. National Research Council. 2000. Copper in drinking water. Committee on Copper in Drinking Water, Board on Environmental Studies and Toxicology, Commission of Life Sciences. Washington, DC: National Academy Press[page needed]

- PMID 9587154.

- PMID 10632232.

- PMID 20817278.

- ^ "Am I at risk of developing dementia?". Alzheimer's Society. Archived from the original on 2012-03-11. Retrieved 2012-06-15.

- S2CID 43106197.

- ^ PMID 12042066.

- ^ "Copper link to Alzheimer's disease". New Scientist. 2003-08-12.

- PMID 23959870.

- S2CID 7954546.

- ^ "Protective role for copper in Alzheimer's disease". Science News. 2009-10-13.

- PMID 22145082.

- PMID 18587525.

- S2CID 20716896.

- PMID 22673823.

- hdl:2027.42/35050.

- PMID 11603956.

- PMID 14623488.

- S2CID 10684986.

- PMID 9924006.

- PMID 11124219.

- PMID 8615373.

- PMID 10383882.

- PMID 10633241.

- PMID 12600855.

- S2CID 40324971.

- PMID 2931973.

- PMID 11121720.

- S2CID 19729409.

- PMID 9587149.

- ^ "Hereditary Diseases". Archived from the original on 2011-07-08. Retrieved 2010-10-20.[full citation needed]

- ^ S2CID 2786287.

- ^ S2CID 9782322.

- PMID 7992686.

- ^ a b "Good Health with Copper". Archived from the original on 2011-07-08. Retrieved 2010-10-20.[full citation needed]

- PMID 11286757.

- PMID 14724838.

- PMID 8615372.

- ^ S2CID 21824137.

- PMID 32041110.

- PMID 9794697.

- S2CID 6075182.

- S2CID 25345871.

- S2CID 31358320.

- S2CID 35973373.

- ^ PMID 9587156.

- PMID 10383878.

- PMID 16305350.

- PMID 18712502.

- PMID 18640301.

- S2CID 1841925.

- PMID 19621939.

- S2CID 23002953.

- S2CID 33101086.

- PMID 2740065.

- PMID 7829172. Archived from the originalon 2016-02-01. Retrieved 2015-08-28.

- PMID 16280039.

- PMID 36724022.

- PMID 17961528.

- ^ .

- ^ PMID 6661260.

- ^ PMID 10643654.

- PMID 16503413.

- PMID 10094614.

- PMID 18313806.

- PMID 20089331.

- S2CID 16812353.

- ^ "Copper connects life - Heath and Nutricion". Archived from the original on 2011-02-27. Retrieved 2010-10-20.[full citation needed]

- ISBN 978-1-292-25166-0.