Maize

| Maize | |

|---|---|

| |

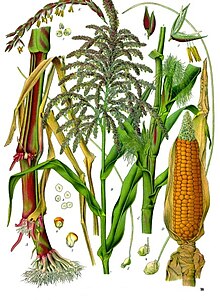

| Includes male and female flowers | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Monocots |

| Clade: | Commelinids |

| Order: | Poales |

| Family: | Poaceae |

| Subfamily: | Panicoideae |

| Genus: | Zea |

| Species: | Z. mays

|

| Binomial name | |

| Zea mays | |

Maize

Maize relies on humans for its propagation. Since the Columbian exchange, it has become a staple food in many parts of the world, with the total production of maize surpassing that of wheat and rice. Much maize is used for animal feed, whether as grain or as the whole plant, which can either be baled or made into the more palatable silage. Sugar-rich varieties called sweet corn are grown for human consumption, while field corn varieties are used for animal feed, for uses such as cornmeal or masa, corn starch, corn syrup, pressing into corn oil, alcoholic beverages like bourbon whiskey, and as chemical feedstocks including ethanol and other biofuels.

Maize is cultivated throughout the world; a greater weight of maize is produced each year than any other grain. In 2020, world production was 1.1 billion tonnes. It is afflicted by many

As a food, maize is used to make a wide variety of dishes including Mexican

History

Pre-Columbian development

Maize

The earliest maize plants grew a single, small ear per plant.

The

Columbian exchange

After the arrival of Europeans in 1492, Spanish settlers consumed maize, and explorers and traders

Maize spread to the rest of the world because of its ability to grow in diverse climates. It was cultivated in Spain just a few decades after Columbus's voyages and then spread to Italy, West Africa and elsewhere.[11] By the 17th century, it was a common peasant food in Southern Europe. By the 18th century, it was the chief food of the southern French and Italian peasantry, especially as polenta in Italy.[12]

When maize was introduced into Western farming systems, it was welcomed for its productivity. However, a widespread problem of malnutrition soon arose wherever it had become a

Names

The name maize derives from the Spanish form maíz of the Taíno mahis.[16] The Swedish botanist Carl Linnaeus used the common name maize as the species epithet in Zea mays.[17] The name Maize is preferred in formal, scientific, and international usage as a common name because it refers specifically to this one grain, unlike corn, which has a complex variety of meanings that vary by context and geographic region.[18] Most countries primarily use the term maize, and the name corn is used mainly in the United States and a handful of other English-speaking countries.[19][20] In countries that primarily use the term maize, the word "corn" may denote any cereal crop, varying geographically with the local staple,[21] such as wheat in England and oats in Scotland or Ireland.[18] The usage of corn for maize started as a shortening of "Indian corn" in 18th century North America.[22]

The historian of food Betty Fussell writes in an article on the history of the word "corn" in North America that "[t]o say the word "corn" is to plunge into the tragi-farcical mistranslations of language and history".[8] Similar to the British usage, the Spanish referred to maize as panizo, a generic term for cereal grains, as did Italians with the term polenta. The British later referred to maize as Turkey wheat, Turkey corn, or Indian corn; Fussell comments that "they meant not a place but a condition, a savage rather than a civilized grain".[8]

International groups such as the

Structure and physiology

Maize is a tall

The grains are usually yellow or white in modern varieties; other varieties have orange, red, brown, blue, purple, or black grains. They are arranged in 8 to 32 rows around the cob; there can be up to 1200 grains on a large cob.[6] Yellow maizes derive their color from carotenoids; red maizes are colored by anthocyanins and phlobaphenes; and orange and green varieties may contain combinations of these pigments.[35]

Maize has short-day

Immature maize shoots accumulate a powerful antibiotic substance, 2,4-dihydroxy-7-methoxy-1,4-benzoxazin-3-one (DIMBOA), which provides a measure of protection against a wide range of pests.[36] Because of its shallow roots, maize is susceptible to droughts, intolerant of nutrient-deficient soils, and prone to being uprooted by severe winds.[37]

-

Many small male flowers make up the male inflorescence, called the tassel.

-

Female inflorescence, with young silk

-

Stalks, ears and silk

-

Full-grown maize plants

-

Mature maize ear on a stalk

-

Male flowers

-

Mature silk

Genomics and genetics

Maize is

The Maize Genetics and Genomics Database is funded by the

Breeding

Conventional breeding

Maize breeding in prehistory resulted in large plants producing large ears. Modern

Since the 1940s, the best strains of maize have been first-generation hybrids made from inbred strains that have been optimized for specific traits, such as yield, nutrition, drought, pest and disease tolerance. Both conventional cross-breeding and genetic engineering have succeeded in increasing output and reducing the need for cropland, pesticides, water and fertilizer. There is conflicting evidence to support the hypothesis that maize yield potential has increased over the past few decades. This suggests that changes in yield potential are associated with leaf angle, lodging resistance, tolerance of high plant density, disease/pest tolerance, and other agronomic traits rather than increase of yield potential per individual plant.[49]

Certain varieties of maize have been bred to produce many ears; these are the source of the "baby corn" used as a vegetable in Asian cuisine.[50][51] A fast-flowering variety named mini-maize was developed to aid scientific research, as multiple generations can be obtained in a single year.[52] One strain called olotón has evolved a symbiotic relationship with nitrogen-fixing microbes, which provides the plant with 29%–82% of its nitrogen.[53] The International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT) operates a conventional breeding program to provide optimized strains. The program began in the 1980s.[54] Hybrid seeds are distributed in Africa by its Drought Tolerant Maize for Africa project.[55]

Tropical

Genetic engineering

Origin

External phylogeny

The maize genus Zea is relatively closely related to sorghum, both being in the PACMAD clade of Old World grasses, and much more distantly to rice and wheat, which are in the other major group of grasses, the BOP clade. It is closely related to Tripsacum, gamagrass.[63]

| (Part of Poaceae) |

| ||||||||||||

Maize and teosinte

Maize is the

In 2004,

Maize pollen dated to 7,300 years ago from

Spreading to the north

Around 4,500 years ago, maize began to spread to the north. In the United States, maize was first cultivated at several sites in New Mexico and Arizona about 4,100 years ago.[7] During the first millennium AD, maize cultivation spread more widely in the areas north. In particular, the large-scale adoption of maize agriculture and consumption in eastern North America took place about A.D. 900. Native Americans cleared large forest and grassland areas for the new crop.[69] The rise in maize cultivation 500 to 1,000 years ago in what is now the southeastern United States corresponded with a decline of freshwater mussels, which are very sensitive to environmental changes.[70]

Agronomy

Growing

Because it is cold-intolerant, in the temperate zones maize must be planted in the spring. Its root system is generally shallow, so the plant is dependent on soil moisture. As a plant that uses C4 carbon fixation, maize is a considerably more water-efficient crop than plants that use C3 carbon fixation such as alfalfa and soybeans. Maize is most sensitive to drought at the time of silk emergence, when the flowers are ready for pollination. In the United States, a good harvest was traditionally predicted if the maize was "knee-high by the Fourth of July", although modern hybrids generally exceed this growth rate. Maize used for silage is harvested while the plant is green and the fruit immature. Sweet corn is harvested in the "milk stage", after pollination but before starch has formed, between late summer and early to mid-autumn. Field maize is left in the field until very late in the autumn to thoroughly dry the grain, and may, in fact, sometimes not be harvested until winter or even early spring. The importance of sufficient soil moisture is shown in many parts of Africa, where periodic drought regularly causes maize crop failure and consequent famine. Although it is grown mainly in wet, hot climates, it can thrive in cold, hot, dry or wet conditions, meaning that it is an extremely versatile crop.[71]

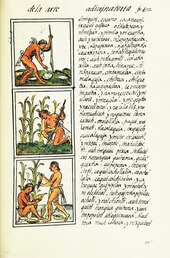

Maize was planted by the Native Americans in small hills of soil, in the polyculture system called the Three Sisters.[72] Maize provided support for beans; the beans provided nitrogen derived from nitrogen-fixing rhizobia bacteria which live on the roots of beans and other legumes; and squashes provided ground cover to stop weeds and inhibit evaporation by providing shade over the soil.[73]

-

Seedlings three weeks after sowing

-

Young stalks

-

Mature plants showing ears

Harvesting

Sweet corn, harvested earlier than maize grown for grain, grows to maturity in a period of from 60 to 100 days according to variety. An extended sweet corn harvest, picked at the milk stage, can be arranged either by planting a selection of varieties which ripen earlier and later, or by planting different areas at fortnightly intervals.[74] Maize harvested as a grain crop can be kept in the field a relatively long time, even months, after the crop is ready to harvest; it can be harvested and stored in the husk leaves if kept dry.[75]

Before World War II, most maize in North America was harvested by hand. This involved a large number of workers and associated social events (husking or shucking bees). From the 1890s onward, some machinery became available to partially mechanize the processes, such as one- and two-row mechanical pickers (picking the ear, leaving the stover) and corn binders, which are reaper-binders designed specifically for maize. The latter produce sheaves that can be shocked. By hand or mechanical picker, the entire ear is harvested, which requires a separate operation of a maize sheller to remove the kernels from the ear. Whole ears of maize were often stored in corn cribs, sufficient for some livestock feeding uses. Today corn cribs with whole ears, and corn binders, are less common because most modern farms harvest the grain from the field with a combine harvester and store it in bins. The combine with a corn head (with points and snap rolls instead of a reel) does not cut the stalk; it simply pulls the stalk down. The stalk continues downward and is crumpled into a mangled pile on the ground, where it usually is left to become organic matter for the soil. The ear of maize is too large to pass between slots in a plate as the snap rolls pull the stalk away, leaving only the ear and husk to enter the machinery. The combine separates the husk and the cob, keeping only the kernels.[76]

-

Harvesting maize, Iowa

-

Harvesting maize, Finland

-

Hand-picking maize, Myanmar

Grain storage

Drying is vital to prevent or at least reduce damage by

Production

Maize is widely cultivated throughout the world, and a greater weight of maize is produced each year than any other grain.[78] In 2020, total world production was 1.16 billion tonnes, led by the United States with 31.0% of the total (table). China produced 22.4% of the global total.[79]

| Top Maize producers | |

|---|---|

| in 2020 | |

| Numbers in million |

-

Production of maize (2019)[81]

Pests

Many pests can affect maize growth and development, including invertebrates, weeds, and pathogens.[83][84]

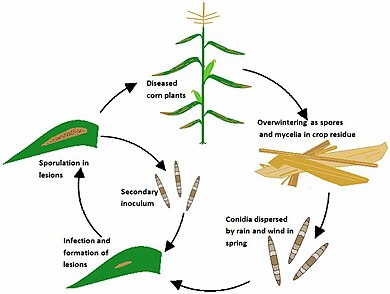

Maize is susceptible to a large number of fungal, bacterial, and viral

Maize sustains a billion dollars' worth of losses annually in the US from each of two major insect

Nematodes too are pests of maize. It is likely that every maize plant harbors some nematode parasites, and populations of Pratylenchus lesion nematodes in the roots can be "enormous". The effects on the plants include stunting, sometimes of whole fields, sometimes in patches, especially when there is also water stress and poor control of weeds.[95]

Many plants, both monocots (grasses) such as Echinochloa crus-galli (barnyard grass) and dicots (forbs) such as Chenopodium and Amaranthus may compete with maize and reduce crop yields. Control may involve mechanical weed removal, flame weeding, or herbicides.[96]

-

Caterpillar of European corn borer in maize

-

Corncob damage by European corn borer

Uses

Culinary

Maize and

In prehistoric times, Mesoamerican women used a

Coarse maize meal is made into a thick

Sweet corn, a genetic variety that is high in sugars and low in starch, is eaten in the unripe state as corn on the cob.[105]

-

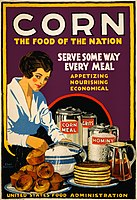

Poster of maize-based foods,

US Food Administration, 1918 -

Semi-peeled corn on the cob

-

Mexicantamales

-

One way of serving Italian polenta

Nutritional value

| Nutritional value per 100 g (3.5 oz) | |

|---|---|

| Energy | 360 kJ (86 kcal) |

18.7 g | |

| Starch | 5.7 g |

| Sugars | 6.26 g |

| Dietary fiber | 2 g |

1.35 g | |

3.27 g | |

| Tryptophan | 0.023 g |

| Threonine | 0.129 g |

| Isoleucine | 0.129 g |

| Leucine | 0.348 g |

| Lysine | 0.137 g |

| Methionine | 0.067 g |

| Cystine | 0.026 g |

| Phenylalanine | 0.150 g |

| Tyrosine | 0.123 g |

| Valine | 0.185 g |

| Arginine | 0.131 g |

| Histidine | 0.089 g |

| Alanine | 0.295 g |

| Aspartic acid | 0.244 g |

| Glutamic acid | 0.636 g |

| Glycine | 0.127 g |

| Proline | 0.292 g |

| Serine | 0.153 g |

Niacin (B3) | 11% 1.77 mg |

| Pantothenic acid (B5) | 14% 0.717 mg |

| Vitamin B6 | 5% 0.093 mg |

| Folate (B9) | 11% 42 μg |

| Vitamin C | 8% 6.8 mg |

| Minerals | Quantity %DV† |

| Iron | 3% 0.52 mg |

| Magnesium | 9% 37 mg |

| Manganese | 7% 0.163 mg |

| Phosphorus | 7% 89 mg |

| Potassium | 9% 270 mg |

| Zinc | 4% 0.46 mg |

| Other constituents | Quantity |

| Water | 75.96 g |

Link to USDA Database entry One ear of medium size (6-3/4" to 7-1/2" long) maize has 90 grams of seeds. | |

| †Percentages estimated using US recommendations for adults,[106] except for potassium, which is estimated based on expert recommendation from the National Academies.[107] | |

Raw, yellow, sweet maize kernels are composed of 76% water, 19%

Animal feed

Maize is a major source of animal feed. As a grain crop, the dried kernels are used as feed. They are often kept on the cob for storage in a corn crib, or they may be shelled off for storage in a grain bin. When the grain is used for feed, the rest of the plant (the corn stover) can be used later as fodder, bedding (litter), or soil conditioner. When the whole maize plant (grain plus stalks and leaves) is used for fodder, it is usually chopped and made into silage, as this is more digestible and more palatable to ruminants than the dried form.[110] Traditionally, maize was gathered into shocks after harvesting, where it dried further. It could then be stored for months until fed to livestock. Silage can be made in silos or in silage wrappers. In the tropics, maize is harvested year-round and fed as green forage to the animals.[111] Baled cornstalks offer an alternative to hay for animal feed, alongside direct grazing of maize grown for this purpose.[112]

-

Cattle wait alongside a fence as a truck distributes a grain feed composed of corn by-products into troughs.

-

Baled cornstalks

Chemicals

Starch from maize can be made into

Biofuel

Feed maize is being used for heating; specialized

-

Farm-based maize silage digester near Neumünster, Germany, 2007, using whole maize plants, not just the grain. The green tarpaulin top cover is held up by the biogas stored in the digester.

In human culture

In Mesoamerica, maize is seen as a vital force, personified as a

-

Maize sculpture, Moche culture, 300 AD, Larco Museum, Lima, Peru

-

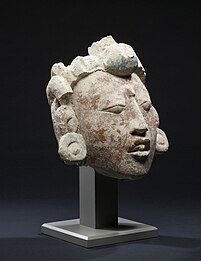

Stucco head of the Maya maize god from Campeche, Mexico, 550–850 AD

-

Jaina Island ceramic statuette of the young Maya maize god emerging from an ear of corn, 600–900 AD

-

Water tower in Rochester, Minnesota being painted as an ear of maize

See also

- Detasseling

- List of sweetcorn varieties

- Post-harvest losses (grains)

- Push–pull technology, pest control strategy for maize and sorghum

- Zein

References

- .

- PMID 11172083.

- ^ PMID 11983901.

- ^ S2CID 83061925.

Recent studies in the Central Balsas River Valley of Mexico, maize's postulated cradle of origin, document the presence of maize phytoliths and starch grains at 8700 BP, the earliest date recorded for the crop (Piperno et al. 2009; Ranere et al. 2009). A large corpus of data indicates that it was dispersed into lower Central America by 7600 BP and had moved into the inter-Andean valleys of Colombia between 7000 and 6000 BP. Given the number of Cauca Valley, Colombia, sites that demonstrate early maize, it is likely that the inter-Andean valleys were a major dispersal route for the crop after it entered South America

- .

- ^ ISBN 978-0-19-967733-7.

- ^ a b c Roney, John (Winter 2009). "The Beginnings of Maize Agriculture". Archaeology Southwest. 23 (1): 4.

- ^ ProQuest 209670587.

To say the word "corn" is to plunge into the tragi-farcical mistranslations of language and history. If only the British had followed Columbus in phoneticizing the Taino word mahiz, which the Arawaks named their staple grain, we wouldn't be in the same linguistic pickle we're in today, where I have to explain to someone every year that when Biblical Ruth "stood in tears amid the alien corn" she was standing in a wheat field. But it was a near thing even with the Spaniards, when we read in Columbus' Journals that the grain "which the Indians called maiz... the Spanish called panizo.' The Spanish term was generic for the cereal grains they knew - wheat, millet, barley, oats - as was the Italian term polenta, from Latin pub. As was the English term "corn", which covered grains of all kinds, including grains of salt, as in "corned beef".

French linguistic imperialism, by way of a Parisian botanist in 1536, provided the term Turcicum frumentum, which the British quickly translated into "Turkey wheat", "Turkey corn", and "Indian corn". By Turkey or Indian, they meant not a place but a condition, a savage rather than a civilized grain, with which the Turks concurred, calling it kukuruz, meaning barbaric. - S2CID 59480757.

- hdl:11336/42613.

- ^ a b Earle, Rebecca (2012). The Body of the Conquistador: Food, Race, and the Colonial Experience in Spanish America, 1492–1700. Cambridge University Press. pp. 17, 144, 151.

- JSTOR 3786266.

- ^ "The origins of maize: the puzzle of pellagra". EUFIC > Nutrition > Understanding Food. The European Food Information Council. December 2001. Archived from the original on September 27, 2006. Retrieved September 14, 2006.

- ISBN 978-1-4419-0471-3.

- ISBN 978-0-13-429880-1.

- ^ "maize, n. (and adj.)". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

- S2CID 4640742.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-8493-8980-1.

The word "maize" is preferred in international usage because in many countries the term "corn", the name by which the plant is known in the United States, is synonymous with the leading cereal grain; thus, in England "corn" refers to wheat, and in Scotland and Ireland it refers to oats.

- ISBN 978-0199739226. Retrieved February 15, 2023.

The use of the word "corn" for what is termed "maize" by most other countries is peculiar to the United States. Europeans who were accustomed to the names "wheat corn", "barley corn", and "rye corn" for other small-seeded cereal grains referred to the unique American grain maize as "Indian corn." The term was shortened to just "corn", which has become the American word for the plant of American genesis.

- ^ Espinoza, Mauricio (April 1, 2015). "'All Corn Is the Same,' and Other Foolishness about America's King of Crops". Ohio State University: College of Food, Agricultural, and Environmental Sciences. Archived from the original on December 3, 2020. Retrieved September 21, 2022.

- ^ "corn, n.1". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

- ISBN 0394400755.

Corn, in orthodox English, means grain for human consumption, especially wheat, e.g., the Corn Laws. The earliest settlers, following this usage, gave the name of Indian corn to what the Spaniards, following the Indians themselves, had called maiz. . . . But gradually the adjective fell off, and by the middle of the Eighteenth Century maize was simply called corn and grains in general were called breadstuffs. Thomas Hutchinson, discoursing to George III in 1774, used corn in this restricted sense speaking of "rye and corn mixed." "What corn?" asked George. "Indian corn," explained Hutchinson, "or as it is called in authors, maize."

- ^ "Zea mays (maize)". CABI. Retrieved September 16, 2022.

- ^ "Maize". FAO. Retrieved September 16, 2022.

- ^ "Overview – ICAR-Indian Institute of Maize Research". Archived from the original on October 5, 2022. Retrieved September 16, 2022.

- ^ "Maize Association - Maize Association Australia". Retrieved September 16, 2022.

- ^ "The Maize Association of Nigeria honors IITA for supporting the nation's agriculture". International Institute of Tropical Agriculture. Retrieved September 16, 2022.

- ^ "SARD-SC Maize component supports the launch of the Ghana Maize Association". International Institute of Tropical Agriculture. March 18, 2016. Retrieved March 10, 2024.

- ^ Du Plessis, Leon. "THE MAIZE TRUST: Custodian of the maize industry". Grain SA. Retrieved March 10, 2024.

- ISSN 0376-835X.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-000-17695-7.

- PMID 22165847.

- ^ "Caryopsis". Merriam Webster. Retrieved January 9, 2024.

- Iowa State University Extension. Retrieved July 24, 2021.

- S2CID 201729476.

- PMID 21910639.

- Monsanto Imagine. October 2, 2008. Archived from the original(PDF) on February 25, 2009. Retrieved February 23, 2009.

- S2CID 254834535.

- ^ Brown, David (November 20, 2009). "Scientists have high hopes for corn genome". The Washington Post.

- ISSN 1940-3402.

- .

- ^ "Welcome to MaizeGDB". MaizeGDB. Retrieved January 11, 2024.

- PMID 35320376.

- ^ "Welcome to MaizeSequence.org". MaizeSequence.org. Archived from the original on September 27, 2013. Retrieved March 12, 2024.

- ^ "Researchers sequence genome of maize, a key crop". Reuters. February 26, 2008. Retrieved October 6, 2014.

- S2CID 21433160.

- PMID 19926864.

- ^ Jugenheimer, Robert W. (1958). "Agricultural Development Paper #62". Hybrid Maize Breeding and Seed Production. Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization.

- S2CID 39657597. Archived from the originalon November 15, 2009.

- ISBN 978-1-78064-174-4.

- .

- PMID 27440866.

- PMID 30086128.

- ^ "About us". CIMMYT. Retrieved March 12, 2024.

- ^ "Drought Tolerant Maize for Africa (DTMA)". CIMMYT. Retrieved March 12, 2024.

- ^ S2CID 24074330.

- PMID 29321632.

- ^ a b James, Clive (2016). "Global Status of Commercialized Biotech/GM Crops: 2016 – ISAAA Brief 52-2016". ISAAA. Archived from the original on May 4, 2017. Retrieved August 26, 2017.

- ^ ISAAA Brief 43-2011: Executive Summary, retrieved September 9, 2012

- ^ .

- ^ "ISAAA Pocket K No. 2: Plant Products of Biotechnology, 2018". Archived from the original on January 30, 2023. Retrieved January 9, 2024.

- ^ Pollack, Andrew (September 23, 2000). "Kraft Recalls Taco Shells With Bioengineered Corn". The New York Times.

- PMID 10860964.

- ^ PMID 21808030.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-471-41184-0.

- PMID 15568971. Archived from the original(PDF) on June 12, 2010. Retrieved May 30, 2010.

- S2CID 8045294.

- ^ PMID 19307570.

- S2CID 129150225.

- S2CID 3679709.

- ISBN 0-205-75930-0.

- ^ Hill, Christina Gish (November 20, 2020). "Returning the 'three sisters' – corn, beans and squash – to Native American farms nourishes people, land and cultures". The Conversation. Retrieved January 9, 2021.

- ISBN 978-1-4000-3205-1.

- ^ "Growing Home Garden Sweet Corn". University of Georgia Extension. Retrieved March 9, 2024.

- ISBN 978-0-471-41184-0.

- ISBN 978-1-118-52492-3.

- ^ Van Devender, Karl (July 2011). "Grain Drying Concepts and Options" (PDF). University of Arkansas Division of Agriculture. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 1, 2016. Retrieved December 15, 2013.

- International Grains Council (international organization) (2013). "International Grains Council Market Report 28 November 2013"(PDF).

- ^ a b "FAOSTAT". FAO.

- ^ "Maize production in 2017, Crops/Regions/Production Quantity from pick lists". United Nations, Food and Agriculture Organization, Statistics Division (FAOSTAT). 2018. Retrieved March 15, 2020.

- S2CID 240163091.

- .

- ^ "Corn Pests". Utah State University. Retrieved January 11, 2024.

- ^ Mueller, Daren; Pope, Rich, eds. (2009). Corn Field Guide (PDF). Iowa State University Extension. Retrieved January 11, 2024.

- ^ "Diseases and Disorders of Corn". Province of Manitoba - Agriculture. Retrieved January 11, 2024.

- ^ Wise, Kiersten. "Diseasees of Corn: Northern Corn Leaf Blight" (PDF). Purdue University. Retrieved January 11, 2024.

- S2CID 87234896.

- ^ "Corn Disease Loss Estimates From the United States and Ontario, Canada — 2022". cropprotectionnetwork.org. Retrieved January 11, 2024.

- ^ Hodgson, Erin W. (2008) Utah State University Extension and Utah Plant Pest Diagnostic Laboratory. Western corn rootworm

- ^ Ostlie, K.R.; et al. "Bt Corn & European Corn Borer: Long-Term Success Through Resistance Management". University of Minnesota Extension Office. Archived from the original on September 28, 2013.

- S2CID 251087338. Retrieved January 11, 2024.

- ^ "fall armyworm, Spodoptera frugiperda (J.E. Smith)". entnemdept.ufl.edu. Retrieved November 14, 2017.

- ^ "PestWeb | Greater Rice Weevil". Agspsrv34.agric.wa.gov.au. Archived from the original on September 28, 2011. Retrieved July 29, 2010.

- .

- .

- S2CID 73606627.

- ^ "Cornstarch". Merriam-Webster. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved May 14, 2016.

- ^ European Starch Association (June 10, 2013). "Factsheet on Glucose Fructose Syrups and Isoglucose".

- ^ Kiniry, Laura. "Where Bourbon Really Got Its Name and More Tips on America's Native Spirit". Smithsonian.com. June 13, 2013.

- ^ Corn Refiners Association. Corn Oil Archived 2019-04-12 at the Wayback Machine 5th Edition. 2006

- ISBN 978-0199740062.

- ISBN 978-0-19-967733-7.

- ISBN 978-1-60774-205-0.

- ^ Nweke, Felix I. "The cassava transformation in Africa". Food and Agriculture Organization. Retrieved January 8, 2024.

- ISBN 978-0778724919.

- ^ United States Food and Drug Administration (2024). "Daily Value on the Nutrition and Supplement Facts Labels". Retrieved March 28, 2024.

- )

- ^ USDA Database entry

- ^ a b "Chapter 8: Improvement of maize diets; from corporate document: Maize in human nutrition". Food and Agriculture Organization. 1992. Retrieved June 5, 2017.

- ^ Heuzé, V.; Tran, G.; Edouard, N.; Lebas, F. (June 22, 2017). "Maize silage". Feedipedia, a programme by INRA, CIRAD, AFZ and FAO.

- ^ Heuzé, V.; Tran, G.; Edouard, N.; Lebas, F. (June 21, 2017). "Maize green forage". Feedipedia, a programme by INRA, CIRAD, AFZ and FAO.

- ^ "Baled Cornstalks". University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign. Retrieved December 28, 2023.

- ^ "Corn Starch" (PDF). Corn Refiners Association. 2013. Retrieved January 9, 2024.

- PMID 16350125.

- ^ "Corn for Home Heat: A Green Idea That Never Quite Popped". March 2, 2015. Archived from the original on March 3, 2015. Retrieved July 7, 2017.

- PMID 26981155.

- Christian Science Monitor. Retrieved October 6, 2014.

- S2CID 56073239.

- ^ Bassie, Karen (2002). "Corn Deities and the Complementary Male/Female Principle". In Lowell S. Gustafson; Amelia N. Trevelyan (eds.). Ancient Maya Gender Identity and Relations. Westport, Conn. and London: Bergin&Garvey. pp. 169–190. Archived from the original on July 10, 2009. Retrieved December 5, 2007.

- ^ "Corncob or Cornstalk Columns and Capitals". Architect of the Capitol. Retrieved January 11, 2024.

- ^ "Corn Palace History". City of Mitchell. Archived from the original on September 29, 2007. Retrieved October 15, 2007.

- ^ Gordon, Ken (September 28, 2019). "From oddity to cherished Dublin icon, 'Field of Corn' celebrates 25 years". The Columbus Dispatch. Archived from the original on September 30, 2019. Retrieved December 21, 2021.

- ^ Croatian National Bank. Kuna and Lipa, Coins of Croatia Archived June 22, 2009, at the Wayback Machine: 1 Lipa Coin Archived June 28, 2011, at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved on March 31, 2009.

Further reading

- Byerlee, Derek. "The globalization of hybrid maize, 1921–70." Journal of Global History 15.1 (2020): 101–122.

- Clampitt, Cynthia. Maize: How Corn Shaped the U.S. Heartland (2015)

- Bonavia, Duccio (May 13, 2013). Maize: Origin, Domestication, and Its Role in the Development of Culture. ISBN 978-1-107-02303-1.

![Production of maize (2019)[81]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/0/08/Production_of_maize_%282019%29.svg/561px-Production_of_maize_%282019%29.svg.png)

![Maize (pink strip) is the second most widely produced primary crop, after sugarcane, and the first among grain crops.[82]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/49/World_Production_Of_Primary_Crops%2C_Main_Commodities.svg/403px-World_Production_Of_Primary_Crops%2C_Main_Commodities.svg.png)