Cortisone

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation | /ˈkɔːrtɪsoʊn/, /ˈkɔːrtɪzoʊn/ |

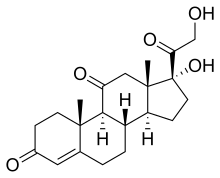

| IUPAC name

17α,21-Dihydroxypregn-4-ene-3,11,20-trione

| |

| Systematic IUPAC name

(1R,3aS,3bS,9aR,9bS,11aS)-1-Hydroxy-1-(hydroxyacetyl)-9a,11a-dimethyl-2,3,3a,3b,4,5,8,9,9a,9b,11,11a-dodecahydro-7H-cyclopenta[a]phenanthrene-7,10(1H)-dione | |

| Other names

17α,21-Dihydroxy-11-ketoprogesterone; 17α-Hydroxy-11-dehydrocorticosterone

| |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (

JSmol ) |

|

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| ChemSpider | |

ECHA InfoCard

|

100.000.149 |

IUPHAR/BPS |

|

| KEGG | |

| MeSH | Cortisone |

PubChem CID

|

|

| UNII | |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA)

|

|

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| C21H28O5 | |

| Molar mass | 360.450 g·mol−1 |

| Melting point | 220 to 224 °C (428 to 435 °F; 493 to 497 K) |

| Pharmacology | |

| H02AB10 (WHO) S01BA03 (WHO) | |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |

Cortisone is a

The term "cortisone" is frequently misused to mean either any corticosteroid or hydrocortisone, which is in fact cortisol. Many who speak of receiving a "cortisone shot" or taking "cortisone" are more likely receiving hydrocortisone or one of many other, much more potent synthetic corticosteroids.

Cortisone can be administered as a prodrug, meaning it has to be converted by the body (specifically the liver, converting it into cortisol) after administration to be effective. It is used to treat a variety of ailments and can be administered

Effects and uses

Cortisone itself is inactive.

A cortisone injection may provide short-term pain relief and may reduce the swelling from

Cortisone is used by

Side effects

Oral use of cortisone has a number of potential systemic adverse effects, including

History

Cortisone was first identified by the American chemists Edward Calvin Kendall and Harold L. Mason while researching at the Mayo Clinic.[10][11][12] During the discovery process, cortisone was known as compound E (while cortisol was known as compound F).

In 1949,

Cortisone was first produced commercially by

Production

Cortisone is one of several end-products of a process called

Because cortisone must be converted to cortisol before being active as a glucocorticoid, its activity is less than simply administering cortisol directly (80–90%).[19]

Popular culture

Addiction to cortisone was the subject of the 1956 motion picture Bigger Than Life, produced by and starring James Mason. Though it was a box-office flop upon its initial release,[20] many modern critics hail the film as a masterpiece and brilliant indictment of contemporary attitudes toward mental illness and addiction.[21] In 1963, Jean-Luc Godard named it one of the ten greatest American sound films ever made.[22]

John F. Kennedy was regularly administered corticosteroids such as cortisone as a treatment for Addison's disease.[23]

See also

Biology portal

Biology portal Medicine portal

Medicine portal- Central serous retinopathy

- Corticosterol

Notes

- ^ a b c "Cortisone shots". MayoClinic.com. 2010-11-16. Retrieved July 31, 2013.

- ^ a b "Prednisone and other corticosteroids: Balance the risks and benefits". MayoClinic.com. 2010-06-05. Retrieved 2017-12-21.

- ISBN 978-0853693000.

- ^ PMID 19837912.

- ^ "injections and needles for coccyx pain". www.coccyx.org.

- PMID 1582609.

- ^ "All About Atopic Dermatitis". National Eczema Association. Archived from the original on 2012-01-30. Retrieved 2013-05-07.

- PMID 13182965.

- S2CID 18658724.

- ^ "Cortisone Discovery and the Nobel Prize". Mayo Clinic. Retrieved 2009-07-04.

- ^ a b c "I Went to See the Elephant" autobiography of Dwight J. Ingle, published by Vantage Press (1963), pg 94, 109

- . Retrieved 2014-09-07.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-7817-6879-5.

- ^ "The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 1950". The Nobel Prize. The Nobel Foundation. 2021. Retrieved 2 April 2021.

- PMID 10070369.

- PMID 13875857.

- ^ Gibbons, Ray (1949). "Science gets synthetic key to rare drug; discovery is made in Chicago". Chicago Tribune. Chicago. p. 1.

- PMID 16337555.

- ^ "Corticosteroid Dose Equivalents". Medscape. Retrieved 20 December 2016.

- ^ Cossar 2011, p. 273.

- ^ Halliwell 2013, pp. 159–162.

- ^ Marshall, Colin (December 2, 2013). "A Young Jean-Luc Godard Picks the 10 Best American Films Ever Made (1963)". Open Culture.

- ^ Altman, Lawrence (October 6, 1992). "The doctor's world; Disturbing Issue of Kennedy's Secret Illness". The New York Times.

Bibliography

- Bonagura J., DVM; et al. (2000). Current Veterinary Therapy. Vol. 13. pp. 321–381.

- Cossar, Harper (2011). Letterboxed: The Evolution of Widescreen Cinema. ISBN 978-0-813-12651-7.

- Halliwell, Martin (2013). Therapeutic Revolutions: Medicine, Psychiatry, and American Culture, 1945-1970. ISBN 978-0-813-56066-3.

- Ingle DJ (October 1950). "The biologic properties of cortisone: a review". J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 10 (10): 1312–54. PMID 14794756.[permanent dead link]

- Woodward R. B.; Sondheimer F.; Taub D. (1951). "The Total Synthesis of Cortisone". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 73 (8): 4057. .