Cosmas Indicopleustes

Cosmas Indicopleustes (

Voyage

Around AD 550, while a monk in the retirement of a

Indicopleustes

"Indicopleustes" means "Indian voyager", from

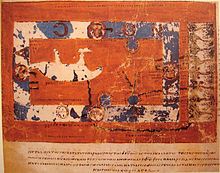

Christian Topography

A major feature of his

However, his idea that the surface of the ocean and earth is nonspherical had been a minority view among educated Western opinion since the 3rd century BC.[10] Cosmas's view was never influential even in religious circles; a near-contemporary Christian, John Philoponus, sought to refute him in his De opificio mundi as did many Christian philosophers of the era.[2]

David C. Lindberg asserts:

Cosmas was not particularly influential in Byzantium, but he is important for us because he has been commonly used to buttress the claim that all (or most) medieval people believed they lived on a flat earth. This claim...is totally false. Cosmas is, in fact, the only medieval European known to have defended a flat earth cosmology, whereas it is safe to assume that all educated Western Europeans (and almost one hundred percent of educated Byzantines), as well as sailors and travelers, believed in the earth's sphericity.[11]

Cosmas was mentioned in Umberto Eco's historical novel, Baudolino. In the book, a Byzantine priest and spy, Zozimas of Chalcedon, refers to his world topography as the key to finding the mythical Prester John:

Well, in the empire of us Romans, centuries ago there lived a great sage, Cosmas Indicopleustes, who traveled to the very confines of the world, and in his Christian Topography demonstrated in irrefutable fashion that the earth truly is in the form of a tabernacle, and that only thus can we explain the most obscure phenomena.[12]

Cosmology aside, Cosmas proves to be an interesting and reliable guide, providing a window into a world that has since disappeared. He happened to be in

See also

References

- ISBN 90-04-13780-7.

- ^ a b Encyclopædia Britannica, 2008, O.Ed, Cosmas Indicopleustes.

- ISBN 978-81-206-1966-1.

- ^ Miller, Hugh (1857). The Testimony of the Rocks. Boston: Gould and Lincoln. p. 428.

- ISBN 978-1-108-01295-9. Retrieved 3 November 2012.

- ISBN 978-0-19-533693-1. Retrieved 3 November 2012.

- ^ a b c One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Cosmas". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 7 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 214.

- Perseus Project.

- ISBN 9781108012959.

- ^ Russell, Jeffrey B. "The Myth of the Flat Earth". American Scientific Affiliation. Retrieved 2007-03-14.

- ^ Lindberg, David "The Beginnings of Western Science, 600 B.C. to A.D. 1450", p. 161

- ^ Eco, Umberto (2002). Baudolino. Orlando, Florida: Harcourt, Inc. p. 215

- .

Further reading

- Kenneth Willis Clark collection of Greek Manuscripts: Cosmas Indicopleustes, Topographia.

- Cosmas Indicopleustes, ed. John Watson McCrindle (1897). The Christian Topography of Cosmas, an Egyptian Monk. ISBN 978-1-108-01295-9)

- Cosmas Indicopleustes, Eric Otto Winstedt (1909). The Christian Topography of Cosmas Indicopleustes. The University Press

- Jeffrey Burton Russell (1997). Inventing the Flat Earth. Praeger Press

- Dr. Jerry H Bentley (2005). Traditions and Encounters. McGraw Hill.

- Schneider, Horst (2011). Kosmas Indikopleustes, Christliche Topographie. Textkritische Analysen. Übersetzung. Kommentar. Turnhout: Brepols.

- Wanda Wolska-Conus. La topographie chrétienne de Cosmas Indicopleustes: théologie et sciences au VIe siècle Vol. 3, Bibliothèque Byzantine. Paris: Presses Universitaires de France, 1962.

- Cosmas Indicopleustes. Cosmas Indicopleustès, Topographie chrétienne. Translated by Wanda Wolska-Conus. 3 vols. Paris: Les Editions du Cerf, 1968–1973.

External links

- The Christian Topography by Cosmas Indicopleustes

- The Christian Topography by Cosmas Indicopleustes (other site)

- Greek Opera Omnia by Migne Patrologia Graeca with analytical indexes

- Scan of the entire Codex Vat.gr.699 on Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana website

This article uses text taken from the Preface to the Online English translation of the Christian Topography, which is in the public domain.