Cosmic microwave background

| Part of a series on |

| Physical cosmology |

|---|

The cosmic microwave background (CMB or CMBR) is

CMB is landmark evidence of the

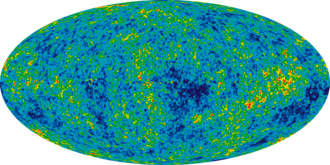

The CMB is not completely smooth and uniform, showing a faint

Importance of precise measurement

Precise measurements of the CMB are critical to cosmology, since any proposed model of the universe must explain this radiation. The CMB has a thermal

The high degree of uniformity throughout the

Other than the temperature and polarization anisotropy, the CMB frequency spectrum is expected to feature tiny departures from the black-body law known as spectral distortions. These are also at the focus of an active research effort with the hope of a first measurement within the forthcoming decades, as they contain a wealth of information about the primordial universe and the formation of structures at late time.[9]

Features

The cosmic microwave background radiation is an emission of uniform,

In the Big Bang model for the formation of the universe, inflationary cosmology predicts that after about 10−37 seconds[14] the nascent universe underwent exponential growth that smoothed out nearly all irregularities. The remaining irregularities were caused by quantum fluctuations in the inflaton field that caused the inflation event.[15] Long before the formation of stars and planets, the early universe was smaller, much hotter and, starting 10−6 seconds after the Big Bang, filled with a uniform glow from its white-hot fog of interacting plasma of photons, electrons, and baryons.

As the universe

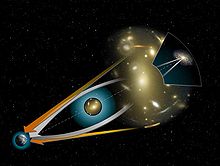

The color temperature of the ensemble of decoupled photons has continued to diminish ever since; now down to 2.7260±0.0013 K,[6] it will continue to drop as the universe expands. The intensity of the radiation corresponds to black-body radiation at 2.726 K because red-shifted black-body radiation is just like black-body radiation at a lower temperature. According to the Big Bang model, the radiation from the sky we measure today comes from a spherical surface called the surface of last scattering. This represents the set of locations in space at which the decoupling event is estimated to have occurred[18] and at a point in time such that the photons from that distance have just reached observers. Most of the radiation energy in the universe is in the cosmic microwave background,[19] making up a fraction of roughly 6×10−5 of the total density of the universe.[20]

Two of the greatest successes of the Big Bang theory are its prediction of the almost perfect black body spectrum and its detailed prediction of the anisotropies in the cosmic microwave background. The CMB spectrum has become the most precisely measured black body spectrum in nature.[10]

The energy density of the CMB is 0.260 eV/cm3 (4.17×10−14 J/m3) which yields about 411 photons/cm3.[21]

History

The cosmic microwave background was first predicted in 1948 by

The 1948 results of Alpher and Herman were discussed in many physics settings through about 1955, when both left the Applied Physics Laboratory at

The interpretation of the cosmic microwave background was a controversial issue in the 1960s with some proponents of the

Harrison, Peebles, Yu and Zel'dovich realized that the early universe would require inhomogeneities at the level of 10−4 or 10−5.[37][38][39] Rashid Sunyaev later calculated the observable imprint that these inhomogeneities would have on the cosmic microwave background.[40] Increasingly stringent limits on the anisotropy of the cosmic microwave background were set by ground-based experiments during the 1980s. RELIKT-1, a Soviet cosmic microwave background anisotropy experiment on board the Prognoz 9 satellite (launched 1 July 1983) gave upper limits on the large-scale anisotropy. The NASA COBE mission clearly confirmed the primary anisotropy with the Differential Microwave Radiometer instrument, publishing their findings in 1992.[41][42] The team received the Nobel Prize in physics for 2006 for this discovery.

Inspired by the COBE results, a series of ground and balloon-based experiments measured cosmic microwave background anisotropies on smaller angular scales over the next decade. The primary goal of these experiments was to measure the scale of the first acoustic peak, which COBE did not have sufficient resolution to resolve. This peak corresponds to large scale density variations in the early universe that are created by gravitational instabilities, resulting in acoustical oscillations in the plasma.

The second peak was tentatively detected by several experiments before being definitively detected by

Predictions prior to the Big Bang interpretation

There are challenges to the standard CMB intepretation within the big bang framework. The background temperature of space was predicted by Charles Édouard Guillaume, Arthur Eddington, Erich Regener, Walther Nernst, Gerhard Herzberg, Erwin Finlay-Freundlich, Max Born, and Anthony Peratt, based on a universe without expansion, and prior to the discovery of the CMB. Their predictions were more accurate than big bang models.[citation needed] The earliest known estimation of the background temperature of “space” was by Guillaume in 1896.[50]

This paper documents the history of predictions.

Alternative interpretations also fit with the Plasma Universe model advocated by Anthony Peratt, and

Relationship to the Big Bang

The cosmic microwave background radiation and the

In the late 1940s Alpher and Herman reasoned that if there was a Big Bang, the expansion of the universe would have stretched the high-energy radiation of the very early universe into the microwave region of the electromagnetic spectrum, and down to a temperature of about 5 K. They were slightly off with their estimate, but they had the right idea. They predicted the CMB. It took another 15 years for Penzias and Wilson to discover that the microwave background was actually there.[53]

According to standard cosmology, the CMB gives a snapshot of the hot early universe at the point in time when the temperature dropped enough to allow electrons and protons to form hydrogen atoms. This event made the universe nearly transparent to radiation because light was no longer being scattered off free electrons. When this occurred some 380,000 years after the Big Bang, the temperature of the universe was about 3,000 K. This corresponds to an ambient energy of about 0.26 eV, which is much less than the 13.6 eV ionization energy of hydrogen.[54] This epoch is generally known as the "time of last scattering" or the period of recombination or decoupling.[55]

Since decoupling, the color temperature of the background radiation has dropped by an average factor of 1,089

- Tr = 2.725 K × (1 + z)

Primary anisotropy

The anisotropy, or directional dependency, of the cosmic microwave background is divided into two types: primary anisotropy, due to effects that occur at the surface of last scattering and before; and secondary anisotropy, due to effects such as interactions of the background radiation with intervening hot gas or gravitational potentials, which occur between the last scattering surface and the observer.

The structure of the cosmic microwave background anisotropies is principally determined by two effects: acoustic oscillations and diffusion damping (also called collisionless damping or Silk damping). The acoustic oscillations arise because of a conflict in the photon–baryon plasma in the early universe. The pressure of the photons tends to erase anisotropies, whereas the gravitational attraction of the baryons, moving at speeds much slower than light, makes them tend to collapse to form overdensities. These two effects compete to create acoustic oscillations, which give the microwave background its characteristic peak structure. The peaks correspond, roughly, to resonances in which the photons decouple when a particular mode is at its peak amplitude.

The peaks contain interesting physical signatures. The angular scale of the first peak determines the curvature of the universe (but not the topology of the universe). The next peak—ratio of the odd peaks to the even peaks—determines the reduced baryon density.[58] The third peak can be used to get information about the dark-matter density.[59]

The locations of the peaks give important information about the nature of the primordial density perturbations. There are two fundamental types of density perturbations called adiabatic and isocurvature. A general density perturbation is a mixture of both, and different theories that purport to explain the primordial density perturbation spectrum predict different mixtures.

- Adiabatic density perturbations

- In an adiabatic density perturbation, the fractional additional number density of each type of particle (baryons, Cosmic inflationpredicts that the primordial perturbations are adiabatic.

- Isocurvature density perturbations

- In an isocurvature density perturbation, the sum (over different types of particle) of the fractional additional densities is zero. That is, a perturbation where at some spot there is 1% more energy in baryons than average, 1% more energy in photons than average, and 2% less energy in neutrinos than average, would be a pure isocurvature perturbation. Hypothetical cosmic strings would produce mostly isocurvature primordial perturbations.

The CMB spectrum can distinguish between these two because these two types of perturbations produce different peak locations. Isocurvature density perturbations produce a series of peaks whose angular scales (ℓ values of the peaks) are roughly in the ratio 1 : 3 : 5 : ..., while adiabatic density perturbations produce peaks whose locations are in the ratio 1 : 2 : 3 : ...[60] Observations are consistent with the primordial density perturbations being entirely adiabatic, providing key support for inflation, and ruling out many models of structure formation involving, for example, cosmic strings.

Collisionless damping is caused by two effects, when the treatment of the primordial plasma as fluid begins to break down:

- the increasing mean free path of the photons as the primordial plasma becomes increasingly rarefied in an expanding universe,

- the finite depth of the last scattering surface (LSS), which causes the mean free path to increase rapidly during decoupling, even while some Compton scattering is still occurring.

These effects contribute about equally to the suppression of anisotropies at small scales and give rise to the characteristic exponential damping tail seen in the very small angular scale anisotropies.

The depth of the LSS refers to the fact that the decoupling of the photons and baryons does not happen instantaneously, but instead requires an appreciable fraction of the age of the universe up to that era. One method of quantifying how long this process took uses the photon visibility function (PVF). This function is defined so that, denoting the PVF by P(t), the probability that a CMB photon last scattered between time t and t + dt is given by P(t) dt.

The maximum of the PVF (the time when it is most likely that a given CMB photon last scattered) is known quite precisely. The first-year WMAP results put the time at which P(t) has a maximum as 372,000 years.[61] This is often taken as the "time" at which the CMB formed. However, to figure out how long it took the photons and baryons to decouple, we need a measure of the width of the PVF. The WMAP team finds that the PVF is greater than half of its maximal value (the "full width at half maximum", or FWHM) over an interval of 115,000 years. By this measure, decoupling took place over roughly 115,000 years, and when it was complete, the universe was roughly 487,000 years old.[citation needed]

Late time anisotropy

Since the CMB came into existence, it has apparently been modified by several subsequent physical processes, which are collectively referred to as late-time anisotropy, or secondary anisotropy. When the CMB photons became free to travel unimpeded, ordinary matter in the universe was mostly in the form of neutral hydrogen and helium atoms. However, observations of galaxies today seem to indicate that most of the volume of the

The CMB photons are scattered by free charges such as electrons that are not bound in atoms. In an ionized universe, such charged particles have been liberated from neutral atoms by ionizing (ultraviolet) radiation. Today these free charges are at sufficiently low density in most of the volume of the universe that they do not measurably affect the CMB. However, if the IGM was ionized at very early times when the universe was still denser, then there are two main effects on the CMB:

- Small scale anisotropies are erased. (Just as when looking at an object through fog, details of the object appear fuzzy.)

- The physics of how photons are scattered by free electrons (Thomson scattering) induces polarization anisotropies on large angular scales. This broad angle polarization is correlated with the broad angle temperature perturbation.

Both of these effects have been observed by the WMAP spacecraft, providing evidence that the universe was ionized at very early times, at a

The time following the emission of the cosmic microwave background—and before the observation of the first stars—is semi-humorously referred to by cosmologists as the

Two other effects which occurred between reionization and our observations of the cosmic microwave background, and which appear to cause anisotropies, are the Sunyaev–Zeldovich effect, where a cloud of high-energy electrons scatters the radiation, transferring some of its energy to the CMB photons, and the Sachs–Wolfe effect, which causes photons from the Cosmic Microwave Background to be gravitationally redshifted or blueshifted due to changing gravitational fields.

Polarization

The cosmic microwave background is

E-modes

E-modes were first seen in 2002 by the Degree Angular Scale Interferometer (DASI).

B-modes

Primordial gravitational waves

Primordial gravitational waves are

On 17 March 2014, it was announced that the

−0.05, which is the amount of power present in gravitational waves compared to the amount of power present in other scalar density perturbations in the very early universe. Had this been confirmed it would have provided strong evidence for cosmic inflation and the Big Bang[69][70][71][72][73][74][75] and against the ekpyrotic model of Paul Steinhardt and Neil Turok.[76] However, on 19 June 2014, considerably lowered confidence in confirming the findings was reported[74][77][78]

Gravitational lensing

The second type of B-modes was discovered in 2013 using the South Pole Telescope with help from the Herschel Space Observatory.[81] In October 2014, a measurement of the B-mode polarization at 150 GHz was published by the POLARBEAR experiment.[82] Compared to BICEP2, POLARBEAR focuses on a smaller patch of the sky and is less susceptible to dust effects. The team reported that POLARBEAR's measured B-mode polarization was of cosmological origin (and not just due to dust) at a 97.2% confidence level.[83]

Microwave background observations

(March 21, 2013)

Subsequent to the discovery of the CMB, hundreds of cosmic microwave background experiments have been conducted to measure and characterize the signatures of the radiation. The most famous experiment is probably the

During the 1990s, the first peak was measured with increasing sensitivity and by 2000 the

In June 2001,

A third space mission, the

On 21 March 2013, the European-led research team behind the

Additional ground-based instruments such as the

Data reduction and analysis

This section may be too technical for most readers to understand. (February 2023) |

Raw CMBR data, even from space vehicles such as WMAP or Planck, contain foreground effects that completely obscure the fine-scale structure of the cosmic microwave background. The fine-scale structure is superimposed on the raw CMBR data but is too small to be seen at the scale of the raw data. The most prominent of the foreground effects is the dipole anisotropy caused by the Sun's motion relative to the CMBR background. The dipole anisotropy and others due to Earth's annual motion relative to the Sun and numerous microwave sources in the galactic plane and elsewhere must be subtracted out to reveal the extremely tiny variations characterizing the fine-scale structure of the CMBR background.

The detailed analysis of CMBR data to produce maps, an angular power spectrum, and ultimately cosmological parameters is a complicated, computationally difficult problem. Although computing a power spectrum from a map is in principle a simple Fourier transform, decomposing the map of the sky into spherical harmonics,[87]

By applying the angular correlation function, the sum can be reduced to an expression that only involves ℓ and power spectrum term The angled brackets indicate the average with respect to all observers in the universe; since the universe is homogeneous and isotropic, therefore there is an absence of preferred observing direction. Thus, C is independent of m. Different choices of ℓ correspond to multipole moments of CMB.

In practice it is hard to take the effects of noise and foreground sources into account. In particular, these foregrounds are dominated by galactic emissions such as Bremsstrahlung, synchrotron, and dust that emit in the microwave band; in practice, the galaxy has to be removed, resulting in a CMB map that is not a full-sky map. In addition, point sources like galaxies and clusters represent another source of foreground which must be removed so as not to distort the short scale structure of the CMB power spectrum.

Constraints on many cosmological parameters can be obtained from their effects on the power spectrum, and results are often calculated using Markov chain Monte Carlo sampling techniques.

CMBR monopole term (ℓ = 0)

When ℓ = 0, the term reduced to 1, and what we have left here is just the mean temperature of the CMB. This "mean" is called CMB monopole, and it is observed to have an average temperature of about Tγ = 2.7255±0.0006 K[87] with one standard deviation confidence. The accuracy of this mean temperature may be impaired by the diverse measurements done by different mapping measurements. Such measurements demand absolute temperature devices, such as the FIRAS instrument on the COBE satellite. The measured kTγ is equivalent to 0.234 meV or 4.6×10−10 mec2. The photon number density of a blackbody having such temperature is . Its energy density is , and the ratio to the critical density is Ωγ = 5.38 × 10−5.[87]

CMBR dipole anisotropy (ℓ = 1)

CMB dipole represents the largest anisotropy, which is in the first spherical harmonic (ℓ = 1). When ℓ = 1, the term reduces to one cosine function and thus encodes amplitude fluctuation. The amplitude of CMB dipole is around 3.3621±0.0010 mK.[87] Since the universe is presumed to be homogeneous and isotropic, an observer should see the blackbody spectrum with temperature T at every point in the sky. The spectrum of the dipole has been confirmed to be the differential of a blackbody spectrum.

CMB dipole is frame-dependent. The CMB dipole moment could also be interpreted as the peculiar motion of the Earth toward the CMB. Its amplitude depends on the time due to the Earth's orbit about the barycenter of the solar system. This enables us to add a time-dependent term to the dipole expression. The modulation of this term is 1 year,[87][88] which fits the observation done by COBE FIRAS.[88][89] The dipole moment does not encode any primordial information.

From the CMB data, it is seen that the Sun appears to be moving at 368±2 km/s relative to the reference frame of the CMB (also called the CMB rest frame, or the frame of reference in which there is no motion through the CMB). The Local Group — the galaxy group that includes our own Milky Way galaxy — appears to be moving at 627±22 km/s in the direction of galactic longitude ℓ = 276°±3°, b = 30°±3°.[87][13] This motion results in an anisotropy of the data (CMB appearing slightly warmer in the direction of movement than in the opposite direction).[87] The standard interpretation of this temperature variation is a simple velocity redshift and blueshift due to motion relative to the CMB, but alternative cosmological models can explain some fraction of the observed dipole temperature distribution in the CMB.

A 2021 study of Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer questions the kinematic interpretation of CMB anisotropy with high statistical confidence.[90]

Multipole (ℓ ≥ 2)

The temperature variation in the CMB temperature maps at higher multipoles, or ℓ ≥ 2, is considered to be the result of perturbations of the density in the early Universe, before the recombination epoch. Before recombination, the Universe consisted of a hot, dense plasma of electrons and baryons. In such a hot dense environment, electrons and protons could not form any neutral atoms. The baryons in such early Universe remained highly ionized and so were tightly coupled with photons through the effect of Thompson scattering. These phenomena caused the pressure and gravitational effects to act against each other, and triggered fluctuations in the photon-baryon plasma. Quickly after the recombination epoch, the rapid expansion of the universe caused the plasma to cool down and these fluctuations are "frozen into" the CMB maps we observe today. The said procedure happened at a redshift of around z ⋍ 1100.[87]

Other anomalies

With the increasingly precise data provided by WMAP, there have been a number of claims that the CMB exhibits anomalies, such as very large scale anisotropies, anomalous alignments, and non-Gaussian distributions.

Ultimately, due to the foregrounds and the cosmic variance problem, the greatest modes will never be as well measured as the small angular scale modes. The analyses were performed on two maps that have had the foregrounds removed as far as possible: the "internal linear combination" map of the WMAP collaboration and a similar map prepared by Max Tegmark and others.[49][56][100] Later analyses have pointed out that these are the modes most susceptible to foreground contamination from synchrotron, dust, and Bremsstrahlung emission, and from experimental uncertainty in the monopole and dipole.

A full

Future evolution

Assuming the universe keeps expanding and it does not suffer a Big Crunch, a Big Rip, or another similar fate, the cosmic microwave background will continue redshifting until it will no longer be detectable,[108] and will be superseded first by the one produced by starlight, and perhaps, later by the background radiation fields of processes that may take place in the far future of the universe such as proton decay, evaporation of black holes, and positronium decay.[109]

Timeline of prediction, discovery and interpretation

Thermal (non-microwave background) temperature predictions

- 1896 – Charles Édouard Guillaume estimates the "radiation of the stars" to be 5–6 K.[50]

- 1926 – Sir Arthur Eddington estimates the non-thermal radiation of starlight in the galaxy "... by the formula E = σT4 the effective temperature corresponding to this density is 3.18° absolute ... black body".[110]

- 1930s – Cosmologist Erich Regenercalculates that the non-thermal spectrum of cosmic rays in the galaxy has an effective temperature of 2.8 K.

- 1931 – Term microwave first used in print: "When trials with wavelengths as low as 18 cm. were made known, there was undisguised surprise+that the problem of the micro-wave had been solved so soon." Telegraph & Telephone Journal XVII. 179/1

- 1934 – black-bodyradiation in an expanding universe cools but remains thermal.

- 1938 – Nobel Prize winner (1920) Walther Nernst reestimates the cosmic ray temperature as 0.75 K.

- 1946 – Robert Dicke predicts "... radiation from cosmic matter" at < 20 K, but did not refer to background radiation.[111]

- 1946 – George Gamow calculates a temperature of 50 K (assuming a 3-billion year old universe),[112] commenting it "... is in reasonable agreement with the actual temperature of interstellar space", but does not mention background radiation.[113]

- 1953 – Erwin Finlay-Freundlich in support of his tired light theory, derives a blackbody temperature for intergalactic space of 2.3 K[114] with comment from Max Born suggesting radio astronomy as the arbitrator between expanding and infinite cosmologies.

Microwave background radiation predictions and measurements

- 1941 – Andrew McKellar detected the cosmic microwave background as the coldest component of the interstellar medium by using the excitation of CN doublet lines measured by W. S. Adams in a B star, finding an "effective temperature of space" (the average bolometric temperature) of 2.3 K.[35][115]

- 1946 – George Gamow calculates a temperature of 50 K (assuming a 3-billion year old universe),[112] commenting it "... is in reasonable agreement with the actual temperature of interstellar space", but does not mention background radiation.

- 1948 – Ralph Alpher and Robert Herman estimate "the temperature in the universe" at 5 K. Although they do not specifically mention microwave background radiation, it may be inferred.[116]

- 1949 – Ralph Alpher and Robert Herman re-re-estimate the temperature at 28 K.

- 1953 – George Gamow estimates 7 K.[111]

- 1956 – George Gamow estimates 6 K.[111]

- 1955 – Émile Le Roux of the Nançay Radio Observatory, in a sky survey at λ = 33 cm, reported a near-isotropic background radiation of 3 kelvins, plus or minus 2.[111]

- 1957 – Tigran Shmaonov reports that "the absolute effective temperature of the radioemission background ... is 4±3 K".[117] It is noted that the "measurements showed that radiation intensity was independent of either time or direction of observation ... it is now clear that Shmaonov did observe the cosmic microwave background at a wavelength of 3.2 cm"[118][119]

- 1960s –

- 1964 – Igor Dmitrievich Novikov publish a brief paper suggesting microwave searches for the black-body radiation predicted by Gamow, Alpher, and Herman, where they name the CMB radiation phenomenon as detectable.[121]

- 1964–65 – James Peebles, P. G. Roll, and D. T. Wilkinsoninterpret this radiation as a signature of the Big Bang.

- 1966 – Rainer K. Sachs and Arthur M. Wolfe theoretically predict microwave background fluctuation amplitudes created by gravitational potential variations between observers and the last scattering surface (see Sachs–Wolfe effect).

- 1968 – Dennis Sciamatheoretically predict microwave background fluctuation amplitudes created by photons traversing time-dependent wells of potential.

- 1969 – Sunyaev–Zel'dovich effect).

- 1983 – Researchers from the Sunyaev–Zel'dovich effect from clusters of galaxies.

- 1983 – RELIKT-1 Soviet CMB anisotropy experiment was launched.

- 1990 – FIRAS on the intergalactic medium.

- January 1992 – Scientists that analysed data from the RELIKT-1 report the discovery of anisotropy in the cosmic microwave background at the Moscow astrophysical seminar.[122]

- 1992 – Scientists that analysed data from COBE DMR report the discovery of anisotropy in the cosmic microwave background.[123]

- 1995 – The Cosmic Anisotropy Telescope performs the first high resolution observations of the cosmic microwave background.

- 1999 – First measurements of acoustic oscillations in the CMB anisotropy angular power spectrum from the TOCO, BOOMERANG, and Maxima Experiments. The BOOMERanG experiment makes higher quality maps at intermediate resolution, and confirms that the universe is "flat".

- 2002 – Polarization discovered by DASI.[124]

- 2003 – E-mode polarization spectrum obtained by the CBI.[125] The CBI and the Very Small Array produces yet higher quality maps at high resolution (covering small areas of the sky).

- 2003 – The Wilkinson Microwave Anisotropy Probe spacecraft produces an even higher quality map at low and intermediate resolution of the whole sky (WMAP provides no high-resolution data, but improves on the intermediate resolution maps from BOOMERanG).

- 2004 – E-mode polarization spectrum obtained by the CBI.[126]

- 2004 – The Arcminute Cosmology Bolometer Array Receiver produces a higher quality map of the high resolution structure not mapped by WMAP.

- 2005 – The Sunyaev–Zel'dovich effect.

- 2005 – Ralph A. Alpher is awarded the National Medal of Sciencefor his groundbreaking work in nucleosynthesis and prediction that the universe expansion leaves behind background radiation, thus providing a model for the Big Bang theory.

- 2006 – The long-awaited three-year polarizationdata.

- 2006 – Two of COBE's principal investigators, George Smoot and John Mather, received the Nobel Prize in Physicsin 2006 for their work on precision measurement of the CMBR.

- 2006–2011 – Improved measurements from WMAP, new supernova surveys ESSENCE and SNLS, and baryon acoustic oscillations from SDSS and WiggleZ, continue to be consistent with the standard Lambda-CDM model.

- 2010 – The first all-sky map from the Planck telescope is released.

- 2013 – An improved all-sky map from the Planck telescope is released, improving the measurements of WMAP and extending them to much smaller scales.

- 2014 – On March 17, 2014, astrophysicists of the

- 2015 – On January 30, 2015, the same team of astronomers from BICEP2 withdrew the claim made on the previous year. Based on the combined data of BICEP2 and Planck, the European Space Agency announced that the signal can be entirely attributed to dust in the Milky Way.[128]

- 2018 – The final data and maps from the Planck telescope is released, with improved measurements of the polarization on large scales.[129]

- 2019 – Planck telescope analyses of their final 2018 data continue to be released.[130]

In popular culture

- In the ancient spaceship, Destiny, was built to study patterns in the CMBR which is a sentient message left over from the beginning of time.[131]

- In Wheelers, a novel (2000) by Ian Stewart & Jack Cohen, CMBR is explained as the encrypted transmissions of an ancient civilization. This allows the Jovian "blimps" to have a society older than the currently-observed age of the universe.[citation needed]

- In The Three-Body Problem, a 2008 novel by Liu Cixin, a probe from an alien civilization compromises instruments monitoring the CMBR in order to deceive a character into believing the civilization has the power to manipulate the CMBR itself.[132]

- The 2017 issue of the Swiss 20 francs bill lists several astronomical objects with their distances – the CMB is mentioned with 430 · 1015 light-seconds.[133]

- In the 2021 Marvel series WandaVision, a mysterious television broadcast is discovered within the Cosmic Microwave Background.[134]

See also

- List of cosmological computation software

- Cosmic neutrino background – Universe's background particle radiation composed of neutrinos

- Cosmic microwave background spectral distortions – Fluctuations in the energy spectrum of the microwave background

- Cosmological perturbation theory – theory by which the evolution of structure is understood in the big bang model

- Axis of evil (cosmology) – Name given to an anomaly in astronomical observations of the Cosmic Microwave Background

- Gravitational wave background – Random background of gravitational waves permeating the Universe

- Heat death of the universe – Possible fate of the universe

- Horizons: Exploring the Universe – Astronomy textbook

- Lambda-CDM model – Model of Big Bang cosmology

- Observational cosmology – Study of the origin of the universe (structure and evolution)

- Observation history of galaxies – Large gravitationally bound system of stars and interstellar matter

- Physical cosmology – Branch of cosmology which studies mathematical models of the universe

- Timeline of cosmological theories – Timeline of theories about physical cosmology

References

- ^ ISBN 978-90-277-0457-3.

- ^ doi:10.1086/148307.

- Lawrence Berkeley Lab. Retrieved 2008-12-11.

- ^ Kaku, M. (2014). "First Second of the Big Bang". How the Universe Works. Season 3. Episode 4. Discovery Science.

- ^ "NASA's "CMB Surface of Last Scatter"". Retrieved 2023-07-05.

- ^ S2CID 119217397.

- S2CID 18570203.

- ^ Baumann, D. (2011). "The Physics of Inflation" (PDF). University of Cambridge. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2018-09-21. Retrieved 2015-05-09.

- S2CID 202539910.

- ^ a b

White, M. (1999). "Anisotropies in the CMB". Proceedings of the Los Angeles Meeting, DPF 99. Bibcode:1999dpf..conf.....W.

- ^

Wright, E.L. (2004). "Theoretical Overview of Cosmic Microwave Background Anisotropy". In W. L. Freedman (ed.). Measuring and Modeling the Universe. Carnegie Observatories Astrophysics Series. ISBN 978-0-521-75576-4.

- S2CID 119185252

- ^ S2CID 5398329

- OCLC 35701222.

- S2CID 36572996.

- Hayden Planetarium. Archived from the originalon 2013-02-13. Retrieved 2008-01-13.

- S2CID 15398837.

- ^ Smoot, G. F. (2006). "Cosmic Microwave Background Radiation Anisotropies: Their Discovery and Utilization". Nobel Lecture. Nobel Foundation. Retrieved 2008-12-22.

- ISBN 978-0-521-82951-9.

- ISBN 978-3-540-67877-9.

- ^ "29. Cosmic Microwave Background: Particle Data Group P.A. Zyla (LBL, Berkeley) et al" (PDF).

- ^ Gamow, G. (1948). "The Origin of Elements and the Separation of Galaxies". .

- ^

Gamow, G. (1948). "The evolution of the universe". S2CID 4793163.

- ^ Alpher, R. A.; Herman, R. C. (1948). "On the Relative Abundance of the Elements". .

- ^

Alpher, R. A.; Herman, R. C. (1948). "Evolution of the Universe". S2CID 4113488.

- ^ Assis, A. K. T.; Neves, M. C. D. (1995). "History of the 2.7 K Temperature Prior to Penzias and Wilson" (PDF). Apeiron (3): 79–87. but see also Wright, E. L. (2006). "Eddington's Temperature of Space". UCLA. Retrieved 2008-12-11.

- ^ a b Overbye, Dennis (5 September 2023). "Back to New Jersey, Where the Universe Began - A half-century ago, a radio telescope in Holmdel, N.J., sent two astronomers 13.8 billion years back in time — and opened a cosmic window that scientists have been peering through ever since". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 5 September 2023. Retrieved 5 September 2023.

- (PDF) from the original on 2006-09-25. Retrieved 2006-10-04.

- ^

Dicke, R. H. (1946). "The Measurement of Thermal Radiation at Microwave Frequencies". S2CID 26658623. This basic design for a radiometer has been used in most subsequent cosmic microwave background experiments.

- ^ "The Cosmic Microwave Background Radiation (Nobel Lecture) by Robert Wilson 8 Dec 1978, p. 474" (PDF).

- ^

Dicke, R. H.; et al. (1965). "Cosmic Black-Body Radiation". doi:10.1086/148306.

- ISBN 978-0-691-01933-8.

- ^ "The Nobel Prize in Physics 1978". Nobel Foundation. 1978. Retrieved 2009-01-08.

- ^ Narlikar, J. V.; Wickramasinghe, N. C. (1967). "Microwave Background in a Steady State Universe" (PDF). (PDF) from the original on 2017-09-22.

- ^ a b

McKellar, A. (1941). "Molecular Lines from the Lowest States of Diatomic Molecules Composed of Atoms Probably Present in Interstellar Space". Publications of the Dominion Astrophysical Observatory. 7 (6). Vancouver, B.C., Canada: 251–272. Bibcode:1941PDAO....7..251M.

- ^

Peebles, P. J. E.; et al. (1991). "The case for the relativistic hot big bang cosmology". S2CID 4337502.

- ^ Harrison, E. R. (1970). "Fluctuations at the threshold of classical cosmology". .

- doi:10.1086/150713.

- ^ Zeldovich, Y. B. (1972). "A hypothesis, unifying the structure and the entropy of the Universe". .

- ^

Doroshkevich, A. G.; Zel'Dovich, Y. B.; Syunyaev, R. A. (1978) [12–16 September 1977]. "Fluctuations of the microwave background radiation in the adiabatic and entropic theories of galaxy formation". In Longair, M. S.; Einasto, J. (eds.). The large scale structure of the universe; Proceedings of the Symposium. Tallinn, Estonian SSR: Dordrecht, D. Reidel Publishing Co. pp. 393–404. Bibcode:1978IAUS...79..393S. While this is the first paper to discuss the detailed observational imprint of density inhomogeneities as anisotropies in the cosmic microwave background, some of the groundwork was laid in Peebles and Yu, above.

- ^

Smoot, G. F.; et al. (1992). "Structure in the COBE differential microwave radiometer first-year maps". S2CID 120701913.

- ^

Bennett, C.L.; et al. (1996). "Four-Year COBE DMR Cosmic Microwave Background Observations: Maps and Basic Results". S2CID 18144842.

- ^

Grupen, C.; et al. (2005). Astroparticle Physics. ISBN 978-3-540-25312-9.

- ^

Miller, A. D.; et al. (1999). "A Measurement of the Angular Power Spectrum of the Microwave Background Made from the High Chilean Andes". S2CID 16534514.

- ^

Melchiorri, A.; et al. (2000). "A Measurement of Ω from the North American Test Flight of Boomerang". S2CID 27518923.

- ^

Hanany, S.; et al. (2000). "MAXIMA-1: A Measurement of the Cosmic Microwave Background Anisotropy on Angular Scales of 10'–5°". S2CID 119495132.

- ^

de Bernardis, P.; et al. (2000). "A flat Universe from high-resolution maps of the cosmic microwave background radiation". S2CID 4412370.

- ^ .

- ^ S2CID 15554608.

- ^ a b Guillaume, C.-É., 1896, La Nature 24, series 2, p. 234, cited in "History of the 2.7 K Temperature Prior to Penzias and Wilson" (PDF)

- S2CID 15606491.

- ISBN 978-0-231-05393-8.

- ^ Assis, A. K. T.; Paulo, São; Neves, M. C. D. (July 1995). "History of the 2.7 K Temperature Prior to Penzias and Wilson" (PDF). Apeiron. 2 (3): 79–87.

- arXiv:astro-ph/9508159.

- ^ "Converted number: Conversion from K to eV".

- ^ a b c

Bennett, C. L.; (WMAP collaboration); Hinshaw, G.; Jarosik, N.; Kogut, A.; Limon, M.; Meyer, S. S.; Page, L.; Spergel, D. N.; Tucker, G. S.; Wollack, E.; Wright, E. L.; Barnes, C.; Greason, M. R.; Hill, R. S.; Komatsu, E.; Nolta, M. R.; Odegard, N.; Peiris, H. V.; Verde, L.; Weiland, J. L.; et al. (2003). "First-year Wilkinson Microwave Anisotropy Probe (WMAP) observations: preliminary maps and basic results". S2CID 115601. This paper warns that "the statistics of this internal linear combination map are complex and inappropriate for most CMB analyses."

- S2CID 118485014.

- ^ Wayne Hu. "Baryons and Inertia".

- ^ Wayne Hu. "Radiation Driving Force".

- S2CID 8791666.

- S2CID 10794058.

- S2CID 9437637.

- S2CID 1731891.

- S2CID 16825580.

- S2CID 30795875.

- S2CID 17330375.

- S2CID 119512504.

- ^ "Scientists Report Evidence for Gravitational Waves in Early Universe". 2014-03-17. Retrieved 2007-06-20.

- ^ a b Staff (17 March 2014). "BICEP2 2014 Results Release". National Science Foundation. Retrieved 18 March 2014.

- ^ a b Clavin, Whitney (March 17, 2014). "NASA Technology Views Birth of the Universe". NASA. Retrieved March 17, 2014.

- ^ a b Overbye, Dennis (March 17, 2014). "Space Ripples Reveal Big Bang's Smoking Gun". The New York Times. Retrieved March 17, 2014.

- ^ a b Overbye, Dennis (March 24, 2014). "Ripples From the Big Bang". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 2022-01-01. Retrieved March 24, 2014.

- ^ "Gravitational waves: have US scientists heard echoes of the big bang?". The Guardian. 2014-03-14. Retrieved 2014-03-14.

- ^ a b c d

Ade, P.A.R. (BICEP2 Collaboration) (2014). "Detection of B-Mode Polarization at Degree Angular Scales by BICEP2". S2CID 22780831.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link - ^ Overbye, Dennis (March 17, 2014). "Space Ripples Reveal Big Bang's Smoking Gun". The New York Times.

- OCLC 271843490.

- ^ a b Overbye, Dennis (June 19, 2014). "Astronomers Hedge on Big Bang Detection Claim". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 2022-01-01. Retrieved June 20, 2014.

- ^ a b Amos, Jonathan (June 19, 2014). "Cosmic inflation: Confidence lowered for Big Bang signal". BBC News. Retrieved June 20, 2014.

- S2CID 9857299.

- ^ Overbye, Dennis (22 September 2014). "Study Confirms Criticism of Big Bang Finding". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 2022-01-01. Retrieved 22 September 2014.

- S2CID 211730550.

- S2CID 118598825.

- ^ "POLARBEAR project offers clues about origin of universe's cosmic growth spurt". Christian Science Monitor. October 21, 2014.

- ^ Clavin, Whitney; Harrington, J.D. (21 March 2013). "Planck Mission Brings Universe Into Sharp Focus". NASA. Retrieved 21 March 2013.

- ^ Staff (21 March 2013). "Mapping the Early Universe". The New York Times. Retrieved 23 March 2013.

- S2CID 119262962.

- ^ . Cosmic Microwave Background review by Scott and Smoot.

- ^ a b Bennett, C. "COBE Differential Microwave Radiometers: Calibration Techniques".

- S2CID 118553819.

- S2CID 222066749.

- S2CID 11586058.

- S2CID 16138962.

- S2CID 15521559.

- S2CID 119463060.

- S2CID 12554281.

- S2CID 5564564.

- arXiv:0907.2731v3 [astro-ph].

- arXiv:1006.1270v1 [astro-ph].

- S2CID 118739762.

- ^

Tegmark, M.; de Oliveira-Costa, A.; Hamilton, A. (2003). "A high resolution foreground cleaned CMB map from WMAP". S2CID 17981329. This paper states, "Not surprisingly, the two most contaminated multipoles are [the quadrupole and octupole], which most closely trace the galactic plane morphology."

- S2CID 118150531.

- S2CID 119443655.

- S2CID 1103733.

- S2CID 6184966.

- S2CID 5238226.

- ^ "Planck shows almost perfect cosmos – plus axis of evil".

- ^ "Found: Hawking's initials written into the universe".

- ^

Krauss, Lawrence M.; Scherrer, Robert J. (2007). "The return of a static universe and the end of cosmology". General Relativity and Gravitation. 39 (10): 1545–1550. S2CID 123442313.

- ^

Adams, Fred C.; Laughlin, Gregory (1997). "A dying universe: The long-term fate and evolution of astrophysical objects". S2CID 12173790.

- ^ Eddington, A., The Internal Constitution of the Stars, cited in "History of the 2.7 K Temperature Prior to Penzias and Wilson" (PDF)

- ^ a b c d e Kragh, H. (1999). Cosmology and Controversy: The Historical Development of Two Theories of the Universe. Princeton University Press. p. 135. .

- ^ ISBN 0-486-43868-6

- ISBN 978-0-486-43868-9.

- ^ Erwin Finlay-Freundlich, "Ueber die Rotverschiebung der Spektrallinien" (1953) Contributions from the Observatory, University of St. Andrews; no. 4, p. 96–102. Finlay-Freundlich gave two extreme values of 1.9K and 6.0K in Finlay-Freundlich, E.: 1954, "Red shifts in the spectra of celestial bodies", Phil. Mag., Vol. 45, pp. 303–319.

- ^

ISBN 978-0-471-92567-5.

- ISBN 0-691-00546-X. "Alpher and Herman first calculated the present temperature of the decoupled primordial radiation in 1948, when they reported a value of 5 K. Although it was not mentioned either then or in later publications that the radiation is in the microwave region, this follows immediately from the temperature ... Alpher and Herman made it clear that what they had called "the temperature in the universe" the previous year referred to a blackbody distributed background radiation quite different from the starlight."

- .

- ^ It is noted that the "measurements showed that radiation intensity was independent of either time or direction of observation ... it is now clear that Shmaonov did observe the cosmic microwave background at a wavelength of 3.2 cm"

- ISBN 978-0-521-85550-1.

- ISBN 978-0-691-00546-1.

- S2CID 96773397.

- ^ Nobel Prize In Physics: Russia's Missed Opportunities, RIA Novosti, Nov 21, 2006

- ^

Sanders, R.; Kahn, J. (13 October 2006). "UC Berkeley, LBNL cosmologist George F. Smoot awarded 2006 Nobel Prize in Physics". UC Berkeley News. Retrieved 2008-12-11.

- S2CID 4359884.

- S2CID 9234000.

- ^ A. Readhead et al., "Polarization observations with the Cosmic Background Imager", Science 306, 836–844 (2004).

- ^ "BICEP2 News | Not Even Wrong".

- S2CID 124938210.

- S2CID 119185252.

- S2CID 198985935.

- ^ Stargate Universe - Robert Carlyle talks about background radiation and Destiny's mission (Video). YouTube. November 10, 2010. Retrieved 2023-02-28.

- ^ Liu, Cixin (2014-09-23). "The Three-Body Problem: "The Universe Flickers"". Tor.com. Retrieved 2023-01-23.

- ^ "Astronomy in your wallet - NCCR PlanetS". nccr-planets.ch. Retrieved 2023-01-23.

- ^ "WandaVision's 'cosmic microwave background radiation' is real, actually". SYFY Official Site. 2021-02-03. Retrieved 2023-01-23.

Further reading

- Balbi, Amedeo (2008). The music of the big bang : the cosmic microwave background and the new cosmology. Berlin: Springer. ISBN 978-3-540-78726-6.

- ISBN 978-0-521-84704-9.

- Evans, Rhodri (2015). The Cosmic Microwave Background: How It Changed Our Understanding of the Universe. Springer. ISBN 978-3-319-09927-9.

External links

- Student Friendly Intro to the CMB A pedagogic, step-by-step introduction to the cosmic microwave background power spectrum analysis suitable for those with an undergraduate physics background. More in depth than typical online sites. Less dense than cosmology texts.

- CMBR Theme on arxiv.org

- Audio: Fraser Cain and Dr. Pamela Gay – Astronomy Cast. The Big Bang and Cosmic Microwave Background – October 2006

- Visualization of the CMB data from the Planck mission

- Copeland, Ed. "CMBR: Cosmic Microwave Background Radiation". Sixty Symbols. Brady Haran for the University of Nottingham.