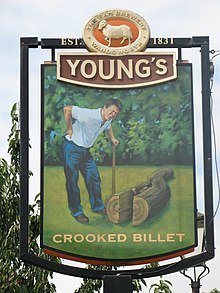

Crooked Billet

Crooked Billet, also known as Shepherd's Hatch Gate,[a] is a hamlet which forms part of Wimbledon Common and incorporates its own commons. The district encompasses a small area in southwest London, England, in the London Borough of Merton. The area is regarded as a popular greenspot and an adjunct to events in Wimbledon.

History

Crooked Billet is a small corner of Wimbledon Common with

It is a small, rather obscure area

After his son died in the Great Plague of London, Robert Pennington, a friend of Charles II, built Southside House (on nearby Woodhayes Road) as a safe haven for his family.[6]

In the 1770s, the "Cinque Cottages" were built on the green, perhaps as an illegal encroachment.[6]

In the 1820s, Gothic House (later renamed Gothic Lodge) was home to novelist Captain

In the 1860s Earl Spencer was Lord of the Manor, and owner of Wimbledon Common. His stated intent to enclose the common land before selling it for building development led to the passage of the Wimbledon and Putney Commons Act of 1871.[16] Consequently, the land is preserved as a commons and saved "for the public in perpetuity". A Board of Conservators manages the property.[1]

In 1872, Sir

In 1888

Notable Resident

Imogen Hassall (1942-1980)

See also

Notes

- ^ Occasionally and erroneously called "Cromwell's Half Acre."[1]

- ^ Quite apart from the location or the present pub, "Crooked Billet" was (and is) a very common pub and inn name. In its most generic form, it refers to a bent staff or branch that has fallen from a tree[7] or ready to be split.[8] There were at least five around London in the 18th century — which then arguably carried a connotation disparaging the presumed clientelle.[9]

- ^ The origin of the name is disputed.[1][14]

- ^ Sir William was the premier campaigner for electric street lighting in Wimbledon. His son, Arthur Preece, opened the town's first electricity power station in 1899.[1]

- ^ Sir Henry was a son of the founder of biscuit maker Peek Frean & Co.[1]

References

Citations

- ^ Walter Cromwell, father of Thomas Cromwellthe Chancellor of Henry VIII. Walter was a 'smith and armourer, a brewer and hostelry keeper' but his 'half acre' is now believed to have been elsewhere across Wimbledon Common.

- ^ Loobey & Every 1995, pp. 8, 50.

- ^ Milward 1989, pp. 81–83.

- ^ "The Treswell Survey". Retrieved 23 February 2019.

- ^ Jane, Fred T. (April 1894). "The Romance of a London Omnibus". The English Illustrated Magazine, London (127): 691–699 – via ProQuest.(subscription required)

- Londonist. Retrieved 9 January 2019.

- Baden-Powell, Baden Henry (1 January 1893). Forest Law: A Course of Lectures on the Principles of Civil and Criminal Law and on the Law of the Forest, Chiefly Based on the Laws in Force in British India, Addressed to the Forest Students at the Royal College of Engineering, Coopers' Hill. Bradbury, Agnew, & Company. p. 329.

- ^ Hitchcock 2004.

- ^ "Food and Drink, London, 11 Best Pubs in London". The Resident. 1 July 2018. Retrieved 10 January 2019.

- Vogue magazine. Retrieved 10 January 2019.

There's more to Wimbledon than the two-week tennis tournament that takes over our screens every year. This leafy south west London district, with its famous SW19 postcode, is just 30 minutes outside of the city smog and a melting pot of hotspots worth a visit - including an idyllic stretch known as Wimbledon Village that borders the common. Here are seven little-known local secrets to make the most of while you're visiting.

- ^ Embley, Jochan (2 July 2018). "Wimbledon tennis: An SW19 area guide, from main attractions to nightlife". Evening Standard. Retrieved 10 January 2019.

Wimbledon is known for one thing above all: tennis. Every July, SW19 is transformed into a hub of activity as fans from all over the world arrive to watch the annual Championships. ... the south-west London neighbourhood is a relaxed, family-friendly area characterised by upmarket, leafy suburbs and green spaces. Its centre is packed with pubs, restaurants and coffee shops.

- ^ Brennan, Ailis (2 July 2018). "Wimbledon Tennis in London: Where to Eat and drink". Evening Standard. Retrieved 10 January 2019.

If you've been inspired to get to grips with the grass but don't feel quite like expending Grand Slam-level energy, then a recline on Wimbledon Common should do the trick. You'll find the Crooked Billet on the corner of the green spot, and with the tennis on the TV, it's the perfect spot for checking the scores over a Pimms.

- ^ "Crooked Billet (also known as Shepherd's Hatch Gate". London Parks and Gardens Trust, parksandgardens.org. Retrieved 1 January 2019.

- ^ Surrey Archaeological Society (1891). Surrey Archaeological Collections: Relating to the History and Antiquities of the County. Vol. 10. Bofworth & Sons. p. 160.

- ^ "The Wimbledon and Putney Commons Act, 1871" (PDF). Wimbledon and Putney Commons. Retrieved 9 January 2019.

- ^ Craig 1989, pp. 465, 467.

- ^ Osbourne 1991.

- ^ Whichelow 1998, pp. 2, 15.

Sources

- ISBN 0-900178-26-4.

- Hitchcock, Tim (1 November 2004). Down and Out in Eighteenth-Century London. London New York: ISBN 9781852852818.

- Loobey, Patrick; Every, Keith (1995). Wimbledon in Old Photographs. Stroud: ISBN 0750907290.

- Milward, R.J. (15 June 1989). Historic Wimbledon: Caesar's Camp to Centre Court. Adlestrop, Moreton-in-Marsh, Gloucestershire: Windrush Press Fielders of Wimbledon, ISBN 0900075163.

- Osbourne, Helen (November 1991). Inn and Around London: A History of Young's Pubs (1st ed.). London: Young & Co's Brewery. ISBN 0951816705.}

- Whichelow, Clive (15 September 1998). Pubs of Wimbledon Village. City: Enigma Publishing. p. 2. ISBN 978-0-9524297-1-5.

External links

- Things to do near the Crooked Billet Trip Advisor