Crossbow

A crossbow is a ranged weapon using an elastic launching device consisting of a bow-like assembly called a prod, mounted horizontally on a main frame called a tiller, which is hand-held in a similar fashion to the stock of a long gun. Crossbows shoot arrow-like projectiles called bolts or quarrels. A person who shoots crossbow is called a crossbowman or an arbalist (after the arbalest, a European crossbow variant used during the 12th century).[1]

Crossbows and bows use the same launch principle, but an archer using a longbow must maintain its draw by pitching the bowstring with fingers, pulling it back with arm and back muscles, and then holding that form while aiming, which demands significant physical strength. A crossbow has a locking mechanism to maintain the draw, limiting the shooter's exertion to pulling the string into the lock and then releasing the shot by depressing a trigger. This enables a crossbowman to handle more draw weight, and to hold it with significantly less physical strain, thus potentially achieving better precision and enabling their effective use by less-skilled personnel. Crossbows are usually drawn by direct pulling, but windlass-like mechanisms requiring less force were sometimes used.

The earliest known crossbows were made in the first millennium BC, as early as the 7th century BC in

In modern times,

Terminology

A crossbowman or crossbow-maker is sometimes called an arbalista, arbalist, or arbalest. The last two are also used to refer to the crossbow.[6]

Arrow, bolt, and quarrel are all suitable terms for crossbow projectiles.[1]

The lath, also called the prod, is the bow of the crossbow. According to W.F. Peterson, the prod came into usage in the 19th century as a result of mistranslating rodd in a 16th-century list of crossbow effects.[1]

The stock is the wooden body on which the bow is mounted, although the medieval tiller is also used.[1]

The lock refers to the release mechanism, including the string, sears, trigger lever, and housing.[1]

Construction

- Nut.

- String.

- Quarrel.

- Trigger.

A crossbow is essentially a

Chinese vertical trigger lock

The Chinese trigger was a mechanism typically composed of three

The nu (弩) [crossbow] is so called because it spreads abroad an aura of rage [nù] (怒) . Its stock is like the arm of a man, therefore it is called bi (臂). That which hooks the bowstring is called ya (牙), for indeed it is like teeth. The part round about the teeth [i.e. the housing box] is called the guo (郭) ["city wall"], since it surrounds the gui (規) [lug] of the teeth [i.e. the locking nut]. Within [and below] there is the xuan dao (懸刀) ["hanging knife", i.e. the trigger blade] so called because it looks like one. The whole assembly is called ji (機)["machine" or "mechanism"], for it is just as ingenious as the loom.[7]

— Shiming

European rolling nut lock

The earliest European designs featured a transverse slot in the top surface of the frame, down into which the string was placed. To shoot this design, a vertical rod is thrust up through a hole in the bottom of the notch, forcing the string out. This rod is usually attached perpendicular to a rear-facing lever called a tickler. A later design implemented a rolling cylindrical pawl called a nut to retain the string. This nut has a perpendicular centre slot for the bolt, and an intersecting axial slot for the string, along with a lower face or slot against which the internal trigger sits. They often also have some form of strengthening internal sear or trigger face, usually of metal. These roller nuts were either free-floating in their close-fitting hole across the stock, tied in with a binding of sinew or other strong cording; or mounted on a metal axle or pins. Removable or integral plates of wood, ivory, or metal on the sides of the stock kept the nut in place laterally. Nuts were made of antler, bone, or metal. Bows could be kept taut and ready to shoot for some time with little physical straining, allowing crossbowmen to aim better without fatiguing.

Bow

Chinese crossbow bows were made of composite material from the start.[1]

European crossbows from the 10th to 12th centuries used wood for the bow, also called the prod or lath, which tended to be

Composite bows started appearing in Europe during the 13th century and could be made from layers of different material, often wood, horn, and sinew glued together and bound with animal tendon. These composite bows made of several layers are much stronger and more efficient in releasing energy than simple wooden bows.[1]

As steel became more widely available in Europe around the 14th century, steel prods came into use.[1]

Traditionally, the prod was often lashed to the stock with rope, whipcord, or other strong cording. This is called the bridle[1]

Spanning mechanism

The Chinese used winches for large crossbows mounted on fortifications or wagons, known as "bedded crossbows" (床弩). Winches may have been used for handheld crossbows during the Han dynasty (202 BC–9 AD, 25–220 AD), but there is only one known depiction of it. The 11th century Chinese military text Wujing Zongyao mentions types of crossbows using winch mechanisms, but it is not known if these were actually handheld crossbows or mounted crossbows.[8] Another drawing method involved the shooters sitting on the ground, and using the combined strength of leg, waist, back and arm muscles to help span much heavier crossbows, which were aptly called "waist-spun crossbows" (腰張弩).

During the medieval era, both Chinese and European crossbows used stirrups as well as belt hooks.[8] In the 13th century, European crossbows started using winches, and from the 14th century an assortment of spanning mechanisms such as winch pulleys, cord pulleys, gaffles (such as gaffe levers, goat's foot levers, and rarer internal lever-action mechanisms), cranequins, and even screws.[1][9]

-

Battle scene depicting a man spanning a crossbow using a winch mechanism, possibly mounted on a frame, Han dynasty

-

Song dynasty cavalry wielding crossbows with stirrups

-

Fifteenth century crossbowman using a stirrup along with a belt hook and pulley

-

Detailed illustration of a goat's foot lever mounted on a crossbow that is half-spanned

-

Illustration of a gaffe lever mounted on a crossbow that is nearly at full-span.

-

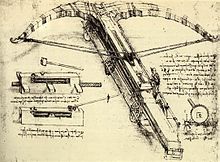

Illustrations of Leonardo da Vinci'srapid fire crossbow in the 15th-century Codex Atlanticus. Note the internal lever mechanism is fully extended to catch the draw string.

-

Internal mechanics illustration of a Balester hunting crossbow's self-spanning mechanism

-

Twentieth century depiction of a windlass pulley

-

Fifteenth century crossbowman using a cranequin (rack & pinion)

-

Iron cranequin, South German, late 15th century

Variants

The smallest crossbows are pistol crossbows. Others are simple long stocks with the crossbow mounted on them. These could be shot from under the arm. The next step in development was stocks of the shape that would later be used

-

Double shot repeating crossbow, also known as the Chu state repeating crossbow (chuguo nu)

-

Mounted double bow crossbow

-

Mounted triple bow crossbow

-

Multi-bolt crossbow without a visible nut or cocking aid

-

Cocking of a Greek gastraphetes

-

Gallo-Roman crossbow

-

Earliest European depiction of cavalry using crossbows, from the Catalan manuscript Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse, 1086.

-

Late medieval crossbowman from ca. 1480

-

A reconstruction of Leonardo da Vinci's rapid fire crossbow as shown at the World of Leonardo Exhibition in Milan.

-

Early modern four-wheeled ballista drawn by armored horses (1552)

-

16th-century French mounted crossbowman (cranequinier). His crossbow is drawn with a rack-and-pinion cranequin, so it can be used while riding.

-

Pistol crossbow for home recreational shooting. Made by Frédéric Siber in Morges, early 19th century, on display at Morges military museum.

-

French cross-bow grenade thrower Arbalète sauterelle type A d'Imphy, circa 1915

Projectiles

The arrow-like projectiles of a crossbow are called

Even relatively small differences in arrow weight can have a considerable impact on its flight trajectory and drop.[11]

Bullet-shooting crossbows are modified crossbows that use bullets or stones as projectiles.

Accessories

The

A major cause of the sound of shooting a crossbow is vibration of various components. Crossbow silencers are multiple components placed on high vibration parts, such as the string and limbs, to dampen vibration and suppress the sound of loosing the bolt.[13]

History

China

In terms of archaeological evidence, crossbow locks made of

The earliest Chinese documents mentioning a crossbow were texts from the 4th to 3rd centuries BC attributed to the

Handheld crossbows with complex bronze trigger mechanisms have also been found with the

It is clear from surviving inventory lists in Gansu and Xinjiang that the crossbow was greatly favored by the Han dynasty. For example, in one batch of slips there are only two mentions of bows, but thirty mentions of crossbows.[23] Crossbows were mass-produced in state armories with designs improving as time went on, such as the use of a mulberry wood stock and brass; a crossbow in 1068 could pierce a tree at 140 paces.[28] Crossbows were used in numbers as large as 50,000 starting from the Qin dynasty and upwards of several hundred thousand during the Han.[29] According to one authority, the crossbow had become "nothing less than the standard weapon of the Han armies", by the second century BC.[30] Han soldiers were required to pull a crossbow with a draw weight equivalent of 76 kg (168 lb) to qualify as an entry level crossbowman,[1] while it was claimed that a few elite troops were capable of bending crossbows with a draw-weight in excess of 340 kg (750 lb) by the hands-and-feet method.[31][32]

After the Han dynasty, the crossbow lost favor during the Six Dynasties, until it experienced a mild resurgence during the Tang dynasty, under which the ideal expeditionary army of 20,000 included 2,200 archers and 2,000 crossbowmen.[33] Li Jing and Li Quan prescribed 20 percent of the infantry to be armed with crossbows.[34]

During the Song dynasty, the crossbow received a huge upsurge in military usage, and often overshadowed the bow 2 to 1 in numbers. During this time period, a stirrup was added for ease of loading. The Song government attempted to restrict the public use of crossbows and sought ways to keep both body armor and crossbows out of civilian ownership.[35] Despite the ban on certain types of crossbows, the weapon experienced an upsurge in civilian usage as both a hunting weapon and pastime. The "romantic young people from rich families, and others who had nothing particular to do" formed crossbow-shooting clubs as a way to pass time.[36]

During the late Ming dynasty, no crossbows were mentioned to have been produced in the three-year period from 1619 to 1622. With 21,188,366 taels, the Ming manufactured 25,134 cannons, 8,252 small guns, 6,425 muskets, 4,090 culverins, 98,547 polearms and swords, 26,214 great "horse decapitator" swords, 42,800 bows, 1,000 great axes, 2,284,000 arrows, 180,000 fire arrows, 64,000 bow strings, and hundreds of transport carts.[37]

Military crossbows were armed by treading, or basically placing the feet on the bow stave and drawing it using one's arms and back muscles. During the Song dynasty, stirrups were added for ease of drawing and to mitigate damage to the bow. Alternatively, the bow could also be drawn by a belt claw attached to the waist, but this was done lying down, as was the case for all large crossbows. Winch-drawing was used for the large mounted crossbows as seen below, but evidence for its use in Chinese hand-crossbows is scant.[8]

There were also other sorts of crossbows, such as the repeating crossbow, multi-shot crossbow, and larger field artillery crossbows.

Southeast Asia

Around the third century BC,

In 315 AD, Nu Wen taught the Chams how to build fortifications and use crossbows. The Chams would later give the Chinese crossbows as presents on at least one occasion.[35]

Crossbow technology for crossbows with more than one prod was transferred from the Chinese to Champa, which Champa used in its invasion of the Khmer Empire's Angkor in 1177.[40] When the Chams sacked Angkor they used the Chinese siege crossbow.[41][42] The Chinese taught the Chams how to use crossbows and mounted archery Crossbows and archery in 1171.[43] The Khmer also had double-bow crossbows mounted on elephants, which Michel Jacq-Hergoualc'h suggests were elements of Cham mercenaries in Jayavarman VII's army.[44]

The native Montagnards of Vietnam's Central Highlands were also known to have used crossbows, as both a tool for hunting, and later an effective weapon against the Viet Cong during the Vietnam War.[45] Montagnard fighters armed with crossbows proved a highly valuable asset to the US Special Forces operating in Vietnam, and it was not uncommon for the Green Berets to integrate Montagnard crossbowmen into their strike teams.[46]

Ancient Greece

The earliest crossbow-like weapons in Europe probably emerged around the late 5th century BC when the

There were also other arrow-shooting machines such as the larger ballista and smaller Scorpio from around 338 BC, but these are torsion catapults and are not considered crossbows.[51][52][53] Arrow-shooting machines (katapeltai) are briefly mentioned by Aeneas Tacticus in his treatise on siegecraft written around 350 BC.[51] An Athenian inventory from 330 to 329 BC includes catapults bolts with heads and flights.[53] Arrow-shooting machines in action are reported from Philip II's siege of Perinthos in Thrace in 340 BC.[54] At the same time, Greek fortifications began to feature high towers with shuttered windows in the top, presumably to house anti-personnel arrow shooters, as in Aigosthena.[55]

Ancient Rome

The late 4th century author

On the textual side, there is almost nothing but passing references in the military historian Vegetius (fl. + 386) to 'manuballistae' and 'arcuballistae' which he said he must decline to describe as they were so well known. His decision was highly regrettable, as no other author of the time makes any mention of them at all. Perhaps the best supposition is that the crossbow was primarily known in late European antiquity as a hunting weapon, and received only local use in certain units of the armies of Theodosius I, with which Vegetius happened to be acquainted.[56]

— Joseph Needham

On the other hand, Arrian's earlier Ars Tactica, from about 136 AD, also mentions 'missiles shot not from a bow but from a machine' and that this machine was used on horseback while in full gallop. It is presumed that this was a crossbow.[1]

The only pictorial evidence of Roman arcuballistas comes from sculptural reliefs in Roman Gaul depicting them in hunting scenes. These are aesthetically similar to both the Greek and Chinese crossbows, but it is not clear what kind of release mechanism they used. Archaeological evidence suggests they were similar to the rolling nut mechanism of medieval Europe.[1]

Medieval Europe

There are essentially no references to the crossbow in Europe from the 5th until the 10th century. There is however a depiction of a crossbow as a hunting weapon on four

The crossbow reappeared again in 947 as a French weapon during the siege of

The crossbow superseded hand bows in many European armies during the 12th century, except in England, where the

Crossbows were eventually replaced in warfare by

Islamic world

There are no references to crossbows in

Mamluk cavalry used crossbows.[1]

Elsewhere and later

In West and Central Africa,[67] crossbows served as a scouting weapon and for hunting, with African slaves bringing this technology to natives in America.[68] In the Southern United States, the crossbow was used for hunting and warfare when firearms or gunpowder were unavailable because of economic hardships or isolation.[68] In the north of Northern America, light hunting crossbows were traditionally used by the Inuit.[69][non-tertiary source needed] These are technologically similar to the African-derived crossbows, but have a different route of influence.

Spanish conquistadors continued to use crossbows in the Americas long after they were replaced in European battlefields by firearms. Only in the 1570s, did firearms become completely dominant among the Spanish in the Americas.[70]

The

A range of crossbows were developed by the

Modern use

Hunting, leisure, and science

Crossbows are used for

-

Modern hunting crossbow

-

Fisheries scientist obtaining tissue samples from dolphins swimming in the bow wave of a NOAA ship

Military and paramilitary

Crossbows are no longer used in battles, but they are still used in some military applications. For example, there is an undated photograph of

In the United States, SAA International Ltd manufacture a 200 J (150 ft⋅lbf) crossbow-launched version of the U.S. Army type classified Launched

In Europe, Barnett International sold crossbows to

In Asia, some Chinese armed forces use crossbows, including the

Comparison to conventional bows

With a crossbow, archers could release a draw force far in excess of what they could have handled with a bow. Furthermore, the crossbow could hold the tension indefinitely, whereas even the strongest longbowman could only hold a drawn bow for a short time. The ease of use of a crossbow allows it to be used effectively with little training, while other types of bows take far more skill to shoot accurately.[89] The disadvantage is the greater weight and clumsiness to reload compared to a bow, as well as the slower rate of shooting and the lower efficiency of the acceleration system, but there would be reduced elastic hysteresis, making the crossbow a more accurate weapon.

Medieval European crossbows had a much smaller draw length than bows, so that, for the same energy to be imparted to the projectile, the crossbow had to have a much higher draw weight.

A direct comparison between a fast hand-drawn replica crossbow and a longbow show a 6:10 rate of shooting[90] or a 4:9 rate within 30 seconds and comparable weapons.[91]

Legislation

Today, the crossbow often has a complicated legal status due to the possibility of lethal use and its similarities to both firearms and bows. While some jurisdictions treat crossbows in the same way as firearms, many others do not require any sort of license to own a crossbow. The legality of using a crossbow for hunting varies widely in different jurisdictions.

See also

References

Citations

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t Loades 2018.

- ^ Tom Ukinski (23 May 2013). "Drones: Mankind's Always Had Them". Guardian Liberty Voice. Retrieved 1 March 2015.

- ISBN 978-1502622310. Archivedfrom the original on 26 November 2022. Retrieved 3 October 2022.

- ISBN 978-1602390102

- ^ "The Rise of the Modern Crossbow". Digital.outdooenebraska.gov.

- ^ [1] [dead link]

- ^ Needham 1994, p. 133.

- ^ a b c Needham 1994, p. 150.

- ^ Ixax, belle. "Crossbow Reviews 2017". Archer's Café. Retrieved 9 March 2017.

- ISBN 0195053591.

- ^ "Crossbow Arrow Drop – Charted Test Results". BestCrossbowSource.com. Retrieved 12 July 2019.

- ^ "Sighting a Crossbow". Best Crossbow Source. Retrieved 28 October 2014.

- ^ "Crossbow". reference.com. Columbia University Press. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 1 March 2015.

- ^ "A Crossbow Mechanism with Some Unique Features from Shandong, China". Asian Traditional Archery Research Network. 18 May 2008. Archived from the original on 18 May 2008. Retrieved 20 August 2008.

- ISBN 9004096329.

- ^ Mao 1998, pp. 109–110.

- ^ Wright 2001, p. 159.

- ^ Needham, Joseph (1986). Science and Civilization in China: Volume 3, Mathematics and the Sciences of the Heavens and the Earth. Taipei: Caves Books Ltd, p. 227.

- ^ Needham 1994, p. 89.

- ^ James Clavell, The Art of War, prelude

- ^ "The Art of War, by Sun Tzu". Archived from the original on 4 May 2018. Retrieved 3 May 2018.

- ^ Needham 1994, p. 34.

- ^ a b Needham 1994, p. 141.

- ^ Needham 1994, p. 139.

- ^ Needham 1994, p. 22.

- ^ Wright 2001, p. 42.

- ^ Needham 1994, pp. 124–128.

- ^ Peers 1996, pp. 130–131.

- ^ Needham 1994, p. 143.

- ^ Graff 2002, p. 22.

- ^ Loades 2018, p. 9.

- ^ Selby 2000, p. 172.

- ^ Graff 2002, p. 193.

- ^ Graff 2016, p. 52.

- ^ a b Needham 1994, p. 145.

- ^ Needham 1994, p. 146.

- ^ Swope 2014, p. 49.

- ^ Kelley 2014, p. 88.

- ^ a b Taylor 1983, p. 21.

- ISBN 978-0756613600.

- ^ Turnbull 2012, p. 42.

- ^ Turnbull 2012, p. 80.

- ^ Turnbull 2012, p. 25.

- ^ Liang 2006, p. [page needed].

- ^ "Montagnard Crossbow, Vietnam". awm.gov.au. Australian War Memorial. Retrieved 4 February 2019.

- ISBN 978-1465466013.

- ^ a b DeVries 2003, p. 127.

- ^ DeVries 2003, p. 128.

- ^ Campbell 2003, pp. 3ff..

- ISBN 0195097424, p. 366

- ^ a b Campbell 2003, pp. 8ff..

- ^ Campbell 2005, pp. 26–56.

- ^ ISBN 978-0198142683, p. 57

- ISBN 978-0198142683, p. 60

- ^ Josiah Ober: Early Artillery Towers: Messenia, Boiotia, Attica, Megarid, American Journal of Archaeology, Vol. 91, No. 4. (1987), S. 569–604 (569)

- ^ a b Needham 1994, p. 172.

- ^ John M. Gilbert, Hunting and Hunting Reserves in Medieval Scotland (Edinburgh: John Donald, 1979), p. 62.

- ^ Needham 1994, p. 170.

- ISBN 0486287203, p. 48

- ISBN 1852604123, p. 75

- ^ "Notes On West African Crossbow Technology". Diaspora.uiuc.edu. Archived from the original on 26 November 2022. Retrieved 14 April 2006.

- ISBN 0486287203, pp. 48–53

- ^ Needham 1994, p. 175.

- ^ ISBN 978-1846032530p. 49

- ISBN 978-1402763120.

- ^ Hired Swords: The Rise of Private Warrior Power in Early Japan, By Karl Friday, Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1992 p. 42

- ^ Baaka pygmy with crossbow Archived 18 March 2009 at the Wayback Machine. Photographersdirect.com. Retrieved on 24 June 2011.

- ^ a b Notes On West African Crossbow Technology Archived 26 November 2022 at the Wayback Machine. Diaspora.uiuc.edu. Retrieved on 24 June 2011.

- ^ Hunting Network (10 February 2009). "The Crossbow: Four thousand years of traditional archery". bowhunting.com. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 1 March 2015.

- S2CID 258861207.

- ^ "The Royal Engineers". The Royal Engineers Journal. 39. The Institution of Royal Engineers: 79. 1925.

- ^ Hugh Chisholm (1922). The Encyclopædia Britannica: 12th Edition 1922, Volume 1. Encyclopædia Britannica Company Limited. p. 470.

- ISSN 1741-6124.

- ^ ISSN 1741-6124.

- ^ "2014 Hunting Regulations Summary" (PDF). Dr6j45jk9xcmk.cloudfront.net. Archived (PDF) from the original on 26 August 2014. Retrieved 27 January 2022.

- ^ "saorbats.com.ar". Saorbats.com.ar. Archived from the original on 5 March 2009.

- ^ CIGS photograph Archived 5 March 2009 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Jane's LGH Mine Clearance by US forces Jul 2009. Janes.com (9 June 2011). Retrieved on 24 June 2011.

- ^ LGH Plastic Retrieval Line Archived 12 February 2010 at the Wayback Machine. None. Retrieved on 24 June 2011.

- ^ SAA Crossbow Launched Grapnel Hook Archived 15 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine. Saa-intl.com. Retrieved on 24 June 2011.

- ^ Richard Norton-Taylor (8 August 1999). "British-made crossbows 'used by Serb soldiers'". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 21 April 2023..

- ^ Day Life Serbia report Archived 12 January 2009 at the Wayback Machine. Daylife.com (15 February 2008). Retrieved on 24 June 2011.

- ^ Greek soldiers uses crossbow Archived 26 November 2022 at the Wayback Machine. I96.photobucket.com

- ^ Turkish special ops Archived 3 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine. I96.photobucket.com

- ^ Spanish Green Beret 2005 photo Archived 12 February 2010 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ New crossbow shoots with great accuracy, archived from the original on 2 February 2014

- ^ Bingham, John. (9 July 2009) "Xinjiang riots: Modern Chinese army displays ancient preference for crossbow". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved on 24 June 2011.

- ^ "Marine Commandos[dead link]". Archived from the original on 25 October 2007. Retrieved 27 January 2022.

- ^ "These Are The Pros and Cons of Crossbow Hunting". Wide Open Spaces. 1 September 2016. Retrieved 11 January 2018.

- ^ Video comparing longbow and crossbow, YouTube. Retrieved 16 September 2010

- ^ longbow vs crossbow behind a pavese, YouTube. Retrieved 16 September 2010

Sources

- ISBN 9781400874446

- Baatz, Dietwulf (1994). "Die römische Jagdarmbrust". Bauten und Katapulte des römischen Heeres. Stuttgart: Franz Steiner Verlag. pp. 284–293. ISBN 3-515-06566-0.

- Campbell, Duncan (2003), Greek and Roman Artillery 399 BCE–CE 363, Oxford: Osprey Publishing, ISBN 1-84176-634-8

- Campbell, Duncan (2005), Ancient Siege Warfare, Osprey Publishing, ISBN 1-84176-770-0

- Crombie, Laura (2016), Archery and Crossbow Guilds in Medieval Flanders, Woodbridge: Boydell and Brewer, ISBN 9781783271047

- DeVries, Kelly Robert (2003), Medieval Military Technology, Petersborough: Broadview Press, ISBN 0-921149-74-3

- Graff, David A. (2002), Medieval Chinese Warfare, 300–900, Warfare and History, London: Routledge, ISBN 0415239559

- Graff, David A. (2016), The Eurasian Way of War: Military practice in seventh-century China and Byzantium, Routledge

- Kelley, Liam C. (2014). "Constructing Local Narratives: Spirits, Dreams, and Prophecies in the Medieval Red River Delta". In Anderson, James A.; Whitmore, John K. (eds.). China's Encounters on the South and Southwest: Reforging the Fiery Frontier Over Two Millennia. United States: Brills. pp. 78–106.

- Liang, Jieming (2006), Chinese Siege Warfare: Mechanical Artillery & Siege Weapons of Antiquity, Singapore, Republic of Singapore: Leong Kit Meng, ISBN 981-05-5380-3

- Loades, Mike (2018), The Crossbow, Osprey

- Lu, Yongxiang (2015), A History of Chinese Science and Technology Volume 3, Springer

- Mao, Ying (1998). "Introduction of Crossbow Mechanism". Southeast Culture. 3.

- Needham, Joseph (1994), Science and Civilization in China Volume 5 Part 6, Cambridge University Press

- Nicolle, David (2003), Medieval Siege Weapons (2): Byzantium, the Islamic World & India AD 476–1526, Osprey Publishing

- Payne-Gallwey, Ralph, Sir, The Crossbow: Mediaeval and Modern, Military and Sporting; its Construction, History & Management with a Treatise on the Balista and Catapult of the Ancients and An Appendix on the Catapult, Balista & the Turkish Bow, New York : Bramhall House, 1958.

- Peers, C. J. (1996), Imperial Chinese Armies (2): 590–1260 AD, Osprey

- Schellenberg, Hans Michael (2006), "Diodor von Sizilien 14,42,1 und die Erfindung der Artillerie im Mittelmeerraum" (PDF), Frankfurter Elektronische Rundschau zur Altertumskunde, 3: 14–23

- Selby, Stephen (2000), Chinese Archery, Hong Kong University Press, ISBN 9622095011

- Swope, Kenneth (2014), The Military Collapse of China's Ming Dynasty, Routledge

- Taylor, Keith Weller (1983). The Birth of Vietnam. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-04428-9.

- Turnbull, Stephen (2001), Siege Weapons of the Far East (1) AD 612–1300, Osprey Publishing

- Turnbull, Stephen (2002), Siege Weapons of the Far East (2) AD 960–1644, Osprey Publishing

- Turnbull, Stephen (2012), Siege Weapons of the Far East (1): AD 612–1300, Bloomsbury Publishing, ISBN 978-1-78200-225-3

- Wright, David Curtis (2001). The History of China. Westport: Greenwood Press. ISBN 031330940X.

External links

- International Crossbow Shooting Union (IAU) Archived 16 July 2020 at the Wayback Machine

- World Crossbow Shooting Association (WCSA)

- The Crossbow by Sir Ralph Payne-Gallwey, BT