Cryptococcosis

| Cryptococcosis | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Busse-Buschke disease, cryptococcic meningitis, cryptococcosis lung, cryptococcosis skin, European Blastomycosis, torular meningitis, torulosis Infectious disease[4] |

| Symptoms |

|

| Causes | Antifungal medication |

| Medication | |

Cryptococcosis is a potentially fatal

It is caused by the

Diagnosis is by isolating Cryptococcus from a sample of affected tissue or direct observation of the fungus by using staining of body fluids.[9] It can be cultured from a cerebrospinal fluid, sputum, and skin biopsy.[9] Treatment is with fluconazole or amphotericin B.[9][10]

Data from 2009 estimated that of the almost one million cases of cryptococcal meningitis that occurred worldwide annually, 700,000 occurred in sub-Saharan Africa and 600,000 per year died.

Classification

Cryptococcus is generally classified according to how it is acquired and its site.[16] It typically begins in the lungs before spreading to other parts of the body, particularly the brain and nervous system.[1] The skin type is less common.[1]

Signs and symptoms

Cough, shortness of breath, chest pain and fever are seen when the lungs are infected, appearing like a pneumonia.[5] There may also be feeling of tiredness.[4] When the brain is infected, symptoms include headache, fever, neck pain, nausea and vomiting, light sensitivity, confusion or changes in behaviour.[5] It can also affect other parts of the body including skin, eyes, bones and prostate.[9] In the skin, it may appear as several fluid-filled nodules with dead tissue.[6] Depending on the site of infection, other features may include loss of vision, blurred vision, inability to move an eye and memory loss.[9]

Symptom onset is often sudden when lungs are infected and gradual over several weeks when the central nervous system is affected.[9]

Cause

Cryptococcosis is a common opportunistic infection for

Distribution is worldwide in soil.[18] The prevalence of cryptococcosis has been increasing over the past 50 years for many reasons, including the increase in incidence of AIDS and the expanded use of immunosuppressive drugs.[19]

In humans, C. neoformans chiefly infects the skin, lungs, and central nervous system (causing meningitis).[19] Less commonly it may affect other organs such as the eye or prostate.[19]

Primary cutaneous cryptococcosis

Primary cutaneous cryptococcosis (PCC) is a distinct clinical diagnosis separate from the secondary cutaneous cryptococcosis that is spread from systematic infection. Males are more likely to develop the infection and a 2020 study showed that the sex bias may be due to a growth hormone, produced by C. neoformans called gibberellic acid (GA) that is upregulated by testosterone.

Morphologic description of the lesions show umbilicated papules, nodules, and violaceous plaques that can mimic other cutaneous diseases like molluscum contagiosum and Kaposi's sarcoma. These lesions may be present months before other signs of system infection in patients with AIDS.[22]

Pulmonary cryptococcosis

Cryptococcus (both C. neoformans and C. gattii) plays a common role in pulmonary invasive mycosis seen in adults with HIV and other immunocompromised conditions.[23] It also affects healthy adults at a much lower frequency and severity as healthy hosts may have no or mild symptoms.[24] Immune-competent hosts may not seek or require treatment, but careful observation may be important.[25] Cryptococcal pneumonia has a potential to disseminate to the central nervous system (CNS) especially in immunocompromised individuals.[26]

Pulmonary cryptococcosis has a worldwide distribution and is commonly underdiagnosed due to limitations in diagnostic capabilities. Since pulmonary nodules are its most common radiological feature, it can clinically and radiologically mimic lung cancer, TB, and other pulmonary mycoses. The sensitivity of cultures and the Cryptococcal (CrAg) antigen with lateral flow device on serum are rarely positive in the absence of disseminated disease.[23] Moreover, pulmonary cryptococcosis worsen the prognosis of cryptococcal meningitis.[23]

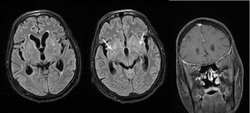

Cryptococcal meningitis

Cryptococcal meningitis (infection of the

Although C. neoformans infection most commonly occurs as an opportunistic infection in immunocompromised people (such as those living with AIDS), C. gattii often infects immunocompetent people as well.[28]

Cryptococcus (both C. neoformans and C. gattii) is the dominant and leading[29] etiologic agent of meningitis in adults with HIV and is considered an "emerging" disease in healthy adults.[30] Though the rate of infection is clearly higher with immunocompromised individuals, some studies suggest a higher mortality rate in patients with non-HIV cryptococcal meningitis secondary to the role of T-cell mediated reaction and injury.[31] CD4+ T cells have proven roles in the defense against Cryptococcus, but it can also contribute to clinical deterioration due its inflammatory response.[32]

Diagnosis

Dependent on the infectious syndrome, symptoms include fever, fatigue, dry cough, headache, blurred vision, and confusion.[33] Symptom onset is often subacute, progressively worsened over several weeks. The two most common presentations are meningitis (an infection in and around the brain) and pulmonary (lung) infection.[19]

Any person who is found to have cryptococcosis at a site outside of the central nervous system (e.g., pulmonary cryptococcosis), a

Cryptococcosis can rarely occur in the non-immunosuppressed people, particularly with Cryptococcus gattii.[citation needed]

Prevention

Cryptococcosis is a very subacute infection with a prolonged subclinical phase lasting weeks to months in persons with HIV/AIDS before the onset of symptomatic meningitis. In Sub-Saharan Africa, the prevalence rates of detectable cryptococcal antigen in peripheral blood is often 4–12% in persons with CD4 counts lower than 100 cells/mcL.[40][41] Cryptococcal antigen screen and preemptive treatment with fluconazole is cost saving to the healthcare system by avoiding cryptococcal meningitis.[42] The World Health Organization recommends cryptococcal antigen screening in HIV-infected persons entering care with CD4<100 cells/μL.[43] This undetected subclinical cryptococcal (if not preemptively treated with anti-fungal therapy) will often go on to develop cryptococcal meningitis, despite receiving HIV therapy.[41][44] Cryptococcosis accounts for 20–25% of the mortality after initiating HIV therapy in Africa. What is effective preemptive treatment is unknown, with the current recommendations on dose and duration based on expert opinion. Screening in the United States is controversial, with official guidelines not recommending screening, despite cost-effectiveness and a 3% U.S. cryptococcal antigen prevalence in CD4<100 cells/μL.[45][46]

Antifungal prophylaxis such as fluconazole and itraconazole reduces the risk of contracting cryptococcosis in those with low CD4 cell count and high risk of developing such disease in a setting of cryptococcal antigen screening tests are not available.[47]

Treatment

Treatment options in persons without HIV-infection have not been well studied.

People living with AIDS often have a greater burden of disease and higher mortality (30–70% at 10-weeks), but recommended therapy is with

The decision on when to start treatment for HIV appears to be very different than other opportunistic infections. A large multi-site trial supports deferring ART for 4–6 weeks was overall preferable with 15% better 1-year survival than earlier ART initiation at 1–2 weeks after diagnosis.[50] A 2018 Cochrane review also supports the delayed starting of treatment until cryptococcosis starts improving with antifungal treatment.[51]

IRIS

The immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome (IRIS) has been described in those with normal immune function with meningitis caused by C. gattii and C. grubii. The increasing inflammation can cause brain injury or be fatal.[52][53][54]

Epidemiology

Cryptococcosis is usually associated with immunosuppressed patients, such as AIDs, corticosteroid use, diabetes, and organ transplant patients.[55] Cryptococcus is found in two species, Cryptococcus neoformans and Cryptococcus gattii.[56] C. gattii was previously thought to only be found in tropical climates and in immunocompetent persons, but recent findings of C. gattii in regions such as Canada and Western regions of North America have challenged this initial presumption of the geographic patterns.[57]

Data from 2009 estimated that of the almost one million cases of cryptococcal meningitis that occurred worldwide annually, 700,000 occurred in sub-Saharan Africa and 600,000 per year died.[13] In 2014, amongst people who had low CD4+ cell count, the annual incidence rate was estimated to be 278,000 cases. Of those, 223,100 resulted in cryptococcal meningitis.[58] About 73% of cryptococcal meningitis cases occurred in Sub-Saharan Africa. More than 180,000 fatalities are attributed to cryptococcal meningitis, 135,000 of which occur in sub-Saharan Africa. Case fatality of cryptococcal meningitis varies widely depending on what country the infection occurs. In low-income countries the case fatality from cryptococcal meningitis is 70%. This differs from middle income countries where the case fatality rate is 40%. Lastly, in wealthy countries the case fatality is 20%.[58] Cryptococcosis is the second most common cause of death for patients with AIDs (about 15%), behind tuberculosis.[59] In sub-Saharan Africa approximately 1/3 of HIV patients will develop cryptococcosis.[60]

In the United States

In the United States there are between 2–7 cases of cryptococcosis per 1,000 per year. Since 1990 the incidence of AIDs associated cryptococcosis fell by 90% due to the proliferation of antiretroviral therapy.[61][62] The estimated prevalence of cryptococcosis cases amongst HIV patients in the U.S. is 2.8%.[63] In immunocompetent patients cryptococcus typically presents itself as Cryptococcus gattii.[62] Despite its rarity cryptococcus has been more commonly seen, with upwards of 20% of cases in immunocompetent people.[64] Over 50% of cryptococcosis infections in North America are caused by C. gattii. Though C. gattii was originally thought to be restricted to subtropical and tropical regions it has become more prevalent worldwide.[65] C. gattii has been found in over 90 people in the United States, most of these cases originating in Washington or Oregon.[66]

In sub-Saharan Africa

Sub-Saharan Africa is the main hub for HIV/AIDS worldwide. HIV/AIDS accounts for about 0.5% of the world's population.[67] Remarkably, sub-Saharan Africa holds 71% of HIV/AIDs cases.[68] Cryptococcal meningitis is a primary contributor to mortality among individuals with HIV/AIDS in sub-Saharan Africa.[69] Approximately 160,000 cases of cryptococcal meningitis are reported in West Africa, resulting in 130,000 deaths in sub-Saharan Africa.[70] Uganda is reported to have the highest occurrence of cryptococcus meningitis.[71] Reflecting that, Ethiopia has the least occurrence.[71] Presently, treatment options involve either a 7 or 14-day regimen of amphotericin-B, coupled with oral antifungal tablets or oral fluconazole. It is important to note, amphotericin-B is not considered a treatment, as it showed not a significant reduction in the mortality rate.[72]

Other animals

Cryptococcosis is also seen in cats and occasionally dogs. It is the most common deep fungal disease in cats, usually leading to chronic infection of the nose and sinuses, and skin ulcers. Cats may develop a bump over the bridge of the nose from local tissue inflammation. It can be associated with

References

- ^ a b c "Cryptococcosis". NORD (National Organization for Rare Disorders). Retrieved 5 June 2021.

- ^ "Cryptococcosis". Lexico UK English Dictionary. Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on 2021-05-07.

- ^ "Cryptococcosis". Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary. Retrieved 2016-01-21.

- ^ a b c d "ICD-11 - ICD-11 for Mortality and Morbidity Statistics". icd.who.int. Retrieved 5 June 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f "Symptoms of C. neoformans Infection | Fungal Diseases | CDC". www.cdc.gov. 14 January 2021. Retrieved 6 June 2021.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-7020-6830-0.

- ^ "C. neoformans Infection | Fungal Diseases | CDC". www.cdc.gov. 29 December 2020. Retrieved 5 June 2021.

- ^ "Where C. gattii Infection Comes From | Fungal Disease | CDC". www.cdc.gov. 29 January 2021. Retrieved 5 June 2021.

- ^ PMID 26897067.

- ^ a b "Treatment for C. neoformans Infection | Fungal Diseases | CDC". www.cdc.gov. 14 January 2021. Retrieved 6 June 2021.

- ^ a b "Where C. neoformans Infection Comes From | Fungal Diseases | CDC". www.cdc.gov. 2 February 2021. Retrieved 5 June 2021.

- PMID 23075448.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-323-41649-8.

- ^ Walter JE, Atchison RW. Epidemiological and immunological studies of Cryptococcus neoformans. J Bacteriol. 1966 Jul;92(1):82-7. doi: 10.1128/JB.92.1.82-87.1966. PMID 5328755; PMCID: PMC276199.

- ^ Beatson M, Harwood M, Reese V, Robinson-Bostom L. Primary cutaneous cryptococcosis in an elderly pigeon breeder. JAAD Case Rep. 2019 May 7;5(5):433-435. doi: 10.1016/j.jdcr.2019.03.006. PMID 31192987; PMCID: PMC6510938.

- PMID 35890028.

- PMID 30329097. Retrieved 2022-08-18.

- ^ "Meningitis: cryptococcal: Overview". Medical Reference: Encyclopedia. University of Maryland Medical Center. September 2010. Archived from the original on 2013-05-23. Retrieved 2011-04-26.

- ^ S2CID 235074157.

- ^ Tucker JS, Guess TE, McClelland EE. The Role of Testosterone and Gibberellic Acid in the Melanization of Cryptococcus neoformans. Front. Microbiol. 2020 Aug 13;11:1921. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2020.01921. PMID 32922377; PMCID: PMC7456850.

- ^ Du L, Yang Y, Gu J, Chen J, Liao W, Zhu Y. Systemic Review of Published Reports on Primary Cutaneous Cryptococcosis in Immunocompetent Patients. Mycopathologia. 2015 Aug;180(1-2):19-25. doi: 10.1007/s11046-015-9880-7. Epub 2015 Mar 4. PMID 25736173.

- ^ Murakawa GJ, Kerschmann R, Berger T. Cutaneous Cryptococcus infection and AIDS. Report of 12 cases and review of the literature. Arch Dermatol. 1996 May;132(5):545-8. PMID 8624151.

- ^ a b c Setianingrum F, Rautemaa-Richardson R, Denning DW. Pulmonary cryptococcosis: A review of pathobiology and clinical aspects. Med Mycol. 2019 Feb 1;57(2):133-150. doi: 10.1093/mmy/myy086. PMID 30329097.

- ^ Choi KH, Park SJ, Min KH, Kim SR, Lee MH, Chung CR, Han HJ, Lee YC. Treatment of asymptomatic pulmonary cryptococcosis in immunocompetent hosts with oral fluconazole. Scand J Infect Dis. 2011 May;43(5):380-5. doi: 10.3109/00365548.2011.552521. Epub 2011 Jan 28. PMID 21271944.

- ^ Saag MS, Graybill RJ, Larsen RA, Pappas PG, Perfect JR, Powderly WG, Sobel JD, Dismukes WE. Practice guidelines for the management of cryptococcal disease. Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2000 Apr;30(4):710-8. doi: 10.1086/313757. Epub 2000 Apr 20. PMID 10770733.

- ^ Brizendine KD, Baddley JW, Pappas PG. Pulmonary cryptococcosis. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2011 Dec;32(6):727-34. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1295720. Epub 2011 Dec 13. PMID 22167400.

- S2CID 5735550.

- PMID 21304167.

- ^ Traoré FA, Cissoko Y, Tounkara TM, Sako FB, Mouelle AD, Kpami DO, Traoré M, Doumbouya M. Étiologies des méningites lymphocytaires chez les personnes vivant avec le VIH suivies dans le service des maladies infectieuses de Conakry [Causes of lymphocytic meningitis in people with HIV admitted to the Infectious Disease department of Conakry]. Med Sante Trop. 2015 Jan-Mar;25(1):52-5. French. doi: 10.1684/mst.2014.0391. PMID 25466555.

- ^ Pasquier E, Kunda J, De Beaudrap P, Loyse A, Temfack E, Molloy SF, Harrison TS, Lortholary O. Long-term Mortality and Disability in Cryptococcal Meningitis: A Systematic Literature Review. Clin Infect Dis. 2018 Mar 19;66(7):1122-1132. doi: 10.1093/cid/cix870. PMID 29028957.

- ^ Anjum S, Williamson PR. Clinical Aspects of Immune Damage in Cryptococcosis. Curr Fungal Infect Rep. 2019 Sep;13(3):99-108. doi: 10.1007/s12281-019-00345-7. Epub 2019 Jul 22. PMID 33101578; PMCID: PMC7580832.

- ^ Neal LM, Xing E, Xu J, Kolbe JL, Osterholzer JJ, Segal BM, Williamson PR, Olszewski MA. CD4+ T Cells Orchestrate Lethal Immune Pathology despite Fungal Clearance during Cryptococcus neoformans Meningoencephalitis. mBio. 2017 Nov 21;8(6):e01415-17. doi: 10.1128/mBio.01415-17. PMID 29162707; PMCID: PMC5698549.

- ^ Barron MA, Madinger NE (November 18, 2008). "Opportunistic Fungal Infections, Part 3: Cryptococcosis, Histoplasmosis, Coccidioidomycosis, and Emerging Mould Infections". Infections in Medicine.

- ^ .

- PMID 8862601.

- ^ PMID 24378231.

- PMID 17642731.

- PMID 16272534.

- PMID 21940419.

- ^ "FIGURE 1. Prevalence of asymptomatic antigenemia with corresponding cost per life saved based on LFA cost of $2.50 per test".

- ^ PMID 20597693.

- PMID 22410867.

- ^ a b c World Health Organization. "Rapid advice: Diagnosis, prevention and management of cryptococcal disease in HIV-infected adults, adolescents, and children". Archived from the original on February 21, 2014. Retrieved 1 August 2012.

- PMID 21786721.

- PMID 22918997.

- PMID 25006824.

- PMID 30156270.

- ^ "Practice Guidelines for the Management of Cryptococcal Disease". Infectious Disease Society of America. 2010. Archived from the original on 2018-07-25. Retrieved 2013-09-14.

- ^ PMID 23055838.

- PMID 24963568.

- PMID 30039850.

- S2CID 42308361.

- PMID 15486830.

- PMID 16619158.

- PMID 28613714, retrieved 2023-11-15

- ^ academic.oup.com https://academic.oup.com/femsyr/article/10/6/769/539826. Retrieved 2023-11-16.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - S2CID 21577621.

- ^ PMID 28483415.

- S2CID 221884476.

- PMID 33402899.

- ^ "C. neoformans Infection Statistics | Fungal Diseases | CDC". www.cdc.gov. 2022-11-02. Retrieved 2023-11-15.

- ^ PMID 28613714, retrieved 2023-11-15

- PMID 33402899.

- ^ https://academic.oup.com/ofid/article/10/8/ofad420/7241483. Retrieved 2023-11-17.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - PMID 36354923.

- S2CID 21577621.

- ^ "HIV and AIDS Epidemic Global Statistics". HIV.gov. Retrieved 2023-12-12.

- PMID 27347270.

- ^ "C. neoformans Infection Statistics | Fungal Diseases | CDC". www.cdc.gov. 2022-11-02. Retrieved 2023-11-26.

- S2CID 221884476.

- ^ PMID 33402899.

- PMID 30488038.

- ^ "Deep Fungal Infections". Archived from the original on 2010-04-13.

- ^ Akira Takeuchi, D. V. M. (July 2014). "Feline Cryptococcosis – WSAVA 2003 Congress – VIN". Vin.com.

Further reading

- Perfect JR, et al. (2010). "Clinical practice guidelines for the management of cryptococcal disease: 2010 update by the infectious diseases society of america". PMID 20047480.

- Gullo FP, et al. (2013). "Cryptococcosis: epidemiology, fungal resistance, and new alternatives for treatment". European Journal of Clinical Microbiology & Infectious Diseases. 32 (11): 1377–1391. S2CID 11317427.

- Perfect JR, et al. (2005). "Cryptococcus neoformans: a sugar-coated killer with designer genes". FEMS Immunology and Medical Microbiology. 45 (11): 395–404. PMID 16055314. (Review)