Culture of the Ottoman Empire

| Culture of the Ottoman Empire |

|---|

|

| Visual arts |

| Performing arts |

| Languages and literature |

| Sports |

| Other |

The culture of the Ottoman Empire evolved over several centuries as the ruling administration of the

As the Ottoman Empire expanded it assimilated the culture of numerous regions under its rule and beyond, being particularly influenced by Turkic, Greco-Roman, Arabic, and Persian culture.

Literature

Poetry

museumAs with many Ottoman Turkish art forms, the poetry produced for the

By the 19th century and the era of Tanzimat reforms, the influence of Turkish folk literature, until then largely oral, began to appear in Turkish poetry, and there was increasing influence from the literature of Europe; there was a corresponding decline in classical court poetry. Tevfik Fikret, born in 1867, is often considered the founder of modern Turkish poetry. Recaizade Mahmud Ekrem, an Ottoman writer and intellectual had also started his early career by writing poems in the newspaper of İbrahim Şinasi, Tasvir-i Efkar. Later in his career he helped a literary movement in the Empire – Servet-i Fünun, to emerge. Recaizade Mahmud Ekrem, had published poems like, Ah Nijad!, Şevki Yok and Güzelim.[2]

Folk literature

Poet-musicians (ozan), were travelling around the Central Asia since the 9th century by telling epics, stories, and performing religious acts with their kopuz This tradition lived in Anatolia in the time of the Seljuk and the Ottoman Empire but with an Islamic intervention. The name aşık was adopted starting from the 14th and 15th centuries, it was an equivalent of the name ozan. Aşıks were the poets with an instrument called bağlama (saz), they were travelling around Anatolia and telling epics from old Turkic tradition with Islamic influence."[3]

Prose

Prior to the 19th century, Ottoman prose was exclusively non-fictional, and was much less highly developed than Ottoman poetry, in part because much of it followed the rules of the originally Arabic tradition of rhymed prose (Saj'). Nevertheless, a number of genres – the travelogue, the political treatise and biography – were current.

From the 19th century, the increasing influence of the European

Architecture

Ottoman architecture was largely a synthesis of

The most significant figure in the field, the 16th-century architect and engineer

Decorative arts

Calligraphy

Calligraphy had a prestigious status under the Ottomans, its traditions having been shaped by the work of

The

Noted Ottoman calligraphers include

Miniatures

The Ottoman tradition of painting miniatures, to illustrate manuscripts or used in dedicated albums, was heavily influenced by the

We can establish approximatively the reign of Mehmed II (1451–81) as a moment of `birth´ of the production of the Ottoman miniatures with the first pieces having been found coming from this era. During that era many manuscripts show a desire in the court to establish a painting studio in the recently annexed capital of the empire Istanbul. This project seems to have succeeded in the 1480s, while we have clear proof of its existence and of the opening of new studios in other cities around 1825.[4]

Carpet-weaving and textile arts

The art of

Jewelry

The Ottoman Empire was noted for the quality of its

Most jewelers and goldsmiths were Christian Armenians and Jews, but the interest of the Ottomans in the related art of watchmaking resulted in many European goldsmiths, watchmakers and gem engravers moving to Constantinople, where they worked in the foreigners' quarter, Galata.[9]

Performance

Music

, 1720.Apart from the music traditions of its constituent peoples, the Ottoman Empire evolved a distinct style of court music,

Another distinctive feature of Ottoman music were the Dancing was an important element of Ottoman culture, which incorporated the folkloric dancing traditions of many different countries and lands on three continents; from the Balkan peninsula and the Black Sea regions to the Caucasus, the Middle East and North Africa.

Dancing was also one of the most popular pastimes in the Harem of Topkapı Palace.

The female belly dancers, named Çengi, were mostly from the Roma community. Today, living in Istanbul's Roma neighbourhoods like Sulukule, Kuştepe, Cennet and Kasımpaşa, they still dominate the traditional belly dancing and musical entertainment shows throughout the city's traditional taverns.

There were also male dancers, named Köçek, who took part in the entertainment shows and celebrations, accompanied by circus acrobats, named Cambaz, performing difficult tricks, and other shows which attracted curiosity.

The meddah or Meddahs were generally traveling artists whose route took them from one large city to another, such along the towns of the spice road; the tradition supposedly goes back to Homer's time. The methods of meddahs were the same as the methods of the itinerant storytellers who related Greek epics such as the Iliad and Odyssey, even though the main stories were now Ferhat ile Şirin or Layla and Majnun. The repertoires of the meddahs also included true stories, modified depending on the audience, artist and political situation.

The Istanbul meddahs were known to integrate musical instruments into their stories: this was a main difference between them and the East Anatolian Dengbejin.

In 2008 the art of the meddahs was relisted in the The Turkish shadow theatre, also known as Karagöz ("Black-Eyed") after one of its main characters, is descended from the Oriental Karagöz shadow play ( In Introduction part, Hacivat enters the stage with the sound of Nareke – a tool that sounds like a buzzing of a bee, and starts reading poems which is an invitation for Karagöz to come to the stage.[12]

In terms of characters, Karagöz and Hacivat was a reflection of Ottoman society. The cosmopolite structure of the Empire – especially of Istanbul, was shown to the audience. Here is the list of some characters of the shadow play:[11]

The Orta Oyunu is an open stage theatric play that consists of two main characters "Kavuklu" and "Pişekar". The play is based on discourse, two main characters of Orta Oyunu tell jokes from one to another to create an environment of humour, similar to Karagöz and Hacivat. However, Medyan's way of playing is more flexible compared to Karagöz and Hacivat.

The first mention of the name Orta Oyunu is in 1834 in the wedding ceremony inscription of Saliha Sultan in those lines of poetry:[13] Cümle etraf-nişin-i meydan oldu / Oldu orta oyunundan handan Medyan took its final form in the start of the 19th century. Seljuk plays that are based on performing imitation and personification were common. However, with the combination of raks (dance), musiki (music), muhavere (discourse), and histrionics the play of Orta Oyunu took its final shape. Other influential plays such as Karagöz and Hacivat, Kukla (puppet play), dans (dance), meddah (encomiastics) and prestidigitation were also significant in the shaping of Medyan, it is because those plays were also based on personification.

The forming elements of Orta Oyunu are the music, different forms of dances and wizardries of the different regions within the Ottoman Empire. Alongside these, cultural way of mocking, mimicking and discourses also have a part to play in Orta Oyunu.

The play took place in an open area where people gathered around the field. Orta Oyunu is unique as it lacks a specific plot, emphasizing improvisation. Music, particularly folk songs and poems, plays a significant role in the performance. Alongside Kavuklu and Pişekar, there are supporting characters such as Curcunabazlar, Çengiler (women dancers), and Köçekler (young men dancers imitating women dancers). Other characters represented various stereotypes from different Ottoman millets, including Arabs, Armenians, Albanians, Kurds, Laz people, and Jews. The performance area was known as the "Meydan" (Square), and there was another space called the "Yeni Dünya" (New World) where men and women audience members observed the play. The men's section was referred to as "mevki" (position), while the women's section was called the "kafes" (cage).[14] İsmail Dümbüllü, who passed away in 1973, was the last notable figure associated with Orta Oyunu.[13]

The Tanzimat period was particularly important in terms of the development of sports and gymnastics in the Ottoman Empire. As other fields like education, the influence of France is the most visible one. It is known that in Mekteb-i Harbiye (Staff Officer Academy), activities of gymnastics were added on the curriculum in 1863 which makes it the first mandatory modern sports lesson of the Empire – Riyazat-ı Bedeniye.[15]

Other schools like Mekteb-i Sultani (Galatasaray Lisesi – Galatasaray High School) and Robert College were the pioneers of the Ottoman Empire in gymnastics. Galatasaray High School was the school of Faik Üstünidman who will later be known as "Şeyhü’l-İdman" because of his leadership in educating gymnastics students. Selim Sırrı Tarcan was also one of the pioneers of sports of the Ottoman Empire, he was the first person who put forward the ideal of competing in the olympic games.

Sultan Abdülaziz after his visits to Europe, ordered the translation of gymnastics books which will be used as school books in the Ottoman Empire. In 1869 Rüştiyeler (Junior High Schools), in 1870 Mekteb-i Tıbbiye (Ottoman Medical School), in 1887 İdadiler (High Schools) were now having gymnastics and fencing classes in their syllabuses.[16]

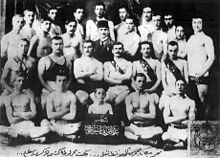

Sports clubs

The Jewish Gymnastics Club of Constantinople, founded in 1895, was the first of Istanbul's sports clubs, soon followed by Kurtuluş Sports Club founded in 1896 by Ottoman Greeks.[17] The opening of these athletic clubs symbolized a general growth in sports and sports culture in Istanbul at the time. In the coming years, Beşiktaş Gymnastics Club, the Galatasaray Sports Club, and the Fenerbahçe Sports Club — Istanbul's "big three" — were founded.[18] Exercise, as well as football and gymnastics were commonplace among the primarily affluent members of these clubs. In contrast to the fairly exclusive "big three", Vefa Sports Club, established after the progressive Young Turk revolution in 1908, served as an amateur sports and football club of the people.[18]

The turn of the twentieth century saw clubs spring up throughout Istanbul to appeal to many niches of young men, whether Muslim, Christian, or Jewish.[19] Almost all athletic clubs were ethnically and religiously homogeneous, however they all shared a focus on physicality.[20] Furthermore, the function of these institutions expanded beyond sports, as they taught young men proper hygiene, dress, and posture, in addition to serving as environments for male discourse and socializing.[19]

The development of athletic clubs enabled the rise of team sports in Istanbul — principally football — serving as contrasts to the more traditional Ottoman sports of oil wrestling and archery.[21] For instance, upon its opening in 1905, Galatasaray functioned exclusively as a football club.[22] This shift toward team competition represented a general modernization of sports in Istanbul, a modernization that can also be seen, for example, in the Beşiktaş Gymnastics Club as traditional Turkish wrestling embraced new mat technology.[23]

Athletic clubs revolutionized sports reporting in the Ottoman Empire, as publications began to cover club games.[24] Futbol, written in Ottoman Turkish and initially released in 1910, served as Istanbul's first sports magazine, principally following club football matches.[25]

Growth in sports related readership coincided with a growing sports spectating culture in Istanbul. 1905 saw the creation of the Constantinople Association Football League, which organized soccer matches among athletic clubs, while also providing entertainment for thousands of spectators.[26] Completed in 1909, with the blessing of Sultan Abdülhamid II, the Union Club provided the first reliable stadium in which thousands of Istanbul spectators could gather to watch sports.[27] Contrary to the strict homosocial exclusivity of many clubs, the Union Club allowed women to spectate athletic competitions.[28] With this rise in spectatorship, Galatasaray and Fenerbahçe in particular, became recognized as the city's preeminent clubs.[29] While heavily connected to football, the Union Club hosted a plethora events organized by a variety of Istanbul athletic clubs, including races, gymnastics, and more. For example, in 1911, the Union Club was the site of the first Armenian Olympics.[30]

In the past century, many of these clubs have only continued to gain popularity. Now under the Republic of Turkey, the Süper Lig represents the region's most popular football league, and Galatasaray and Fenerbahçe are the league's most popular teams.[citation needed]

The cuisine of Ottoman Turkey can be divided between that of the Ottoman court itself, which was a highly sophisticated and elaborate fusion of many of the culinary traditions found in the Empire, its predecessors (notably the Byzantine Empire), and the regional cuisines of the peasantry and of the Empire's minorities, which were influenced by the produce of their respective areas. Rice, for example, was a staple of high-status cookery (Imperial cooks were hired according to the skill they displayed in cooking it) but would have been regarded as a luxury item through most of Anatolia, where bread was the staple grain food.

![]()

Dance

Meddah

Karagöz shadow play

Sections of play and characters

Orta Oyunu or Medyan

Stage and characters

Sports

Ottoman cuisine

Drinks

Food

Gallery

See also

References

![]()

External links

![]()

![Tile with floral and Cloud-band design, c.1578, Iznik Tile, Ottoman Empire, in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.[31]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/8/87/Tile_with_Floral_and_Cloud-band_Design_MET_DP170362.jpg/134px-Tile_with_Floral_and_Cloud-band_Design_MET_DP170362.jpg)