Cumming, Georgia

Cumming, Georgia | ||

|---|---|---|

Cumming City Hall | ||

|

FIPS code 13-20932[3] | | |

| GNIS feature ID | 0331494[4] | |

| Website | www | |

Cumming is a city in

History

The area now called Cumming is located west of the historic location of Vann's Ferry between Forsyth County and Hall County.

Early history

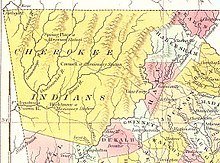

The area, now called Cumming, was inhabited earlier by Cherokee tribes, who are thought to have arrived in the mid-18th century.[citation needed] The Cherokee and Creek people developed disputes over hunting land. After two years of fighting, the Cherokee won the land in the Battle of Taliwa. The Creek people were forced to move south of the Chattahoochee River.[7][8]

The Cherokee coexisted with white settlers until the discovery of gold in Georgia in 1828. Settlers that moved to the area to mine for gold pushed for the removal of the Cherokee. In 1835, the Treaty of New Echota was signed. The treaty stated that the Cherokee Nation must move to the Indian Territory, west of the Mississippi River. This resulted in the Trail of Tears. The Cherokee territory was then formed into Cherokee County in 1831. In 1832, the county had been split into several counties including Forsyth County.[9]

In 1833, the town of Cumming was formed from two 40-acre (16 ha) land lots that had been issued as part of a Georgia State Land Lottery in 1832. The two lots designated as Land Lot 1269 and Land Lot 1270 were purchased by a couple of Forsyth County Inferior Court justices who realized that it was necessary to have a seat of government to conduct county business. The boundaries of the two lots ended at what is now Tolbert Street on the west side, Eastern Circle on the east side, Resthaven Street on the south side, and School Street on the north side. In 1834 the post office was established and began delivering mail. The justices of the Inferior Court divided the town land into smaller lots and began selling them to people over the next several years, reserving one lot for the county courthouse. During that same year, the Georgia State Legislature incorporated the town of Cumming into the City of Cumming and made it the official government seat of Forsyth County.

A second charter was issued in 1845, decreeing that Cumming's government would follow the mayor–council model of government.[10]

The community is commonly thought to be named after Colonel William Cumming.[11] An alternate theory proposed by a local historian posits the name honors Rev. Frederick Cumming, a professor of Jacob Scudder, a resident of the area since 1815 who owned land in present-day downtown.[12] Yet another theory is that the town is named after Alexander Cuming, the son of a Scottish baronet.[13]

Modern history

During the 1830s and 1840s, Cumming benefited from the gold mining industry as many businesses were created to meet the needs of the miners. However, the

1912 racial conflict of Cumming

In 1912, Governor Joseph M. Brown sent four companies of state militia to Cumming to prevent riots after two reported attacks of young white women, allegedly by black men. A suspect in the second assault, in which the victim was also raped and later died, was dragged from the Cumming county jail and lynched. The governor then declared martial law, but the effort did little to stop a month-long barrage of attacks by night riders on the black citizens. This led to the banishment of blacks, and the city had virtually no black population.[14]

Racial tensions were strained again in 1987 when a group of black people were assaulted while camping at a park on Lake Lanier. This was widely reported by local newspapers and in Atlanta. As a result of this, a local businessman[who?] decided to hold a "Peace March" the following week. Civil rights leader Reverend Hosea Williams joined the local businessman in a march along Bethelview and Castleberry Road in south Forsyth County into the City of Cumming where they were assaulted by whites. The marchers retreated and vowed to return. During the following "Brotherhood March" on January 24, 1987, another racially mixed group returned to Forsyth County to complete the march the previous group had been unable to finish. March organizers estimated the number at 20,000, while police estimates ran from 12,000 to 14,000. Hosea Williams and former senator Gary Hart were in the demonstration. A group of the National Guard kept the opposition of about 1,000 in check. Oprah Winfrey featured Cumming and Forsyth County on her The Oprah Winfrey Show. She formed a town hall meeting where one audience member said:

I'm afraid of [blacks] coming to Forsyth County. I was born in Atlanta, and in 1963, the first blacks were bussed to West Fulton High School. I go down there now and I see my neighborhood and my community, which was a nice community, and now it's nothing but a rat-infested slum area because they don't care.[15]

However, most of the audience members agreed that Forsyth County should integrate. Rev. Hosea Williams was excluded from Oprah's show and arrested for trespassing.

City growth

Today, the city is experiencing new growth and bears little resemblance to the small rural town it was mere decades ago. The completion of Georgia 400 has helped turn Cumming into a commuter town for metropolitan Atlanta. The city holds the Cumming Country Fair & Festival every October. The Sawnee Mountain Preserve provides views of the city from the top of Sawnee Mountain.[7] In 1956, Buford Dam, along the Chattahoochee River, started operating. The reservoir that it created is called Lake Lanier.[8] The lake, a popular spot for boaters, has generated income from tourists for Cumming as well as provides a source of drinking water. However, because of rapid growth of the Atlanta area, drought, and mishandling of a stream gauge, Lake Lanier has seen record-low water levels. Moreover, the lake is involved in a longstanding lawsuit between Georgia, Alabama, and Florida. Because of a recent ruling, the city of Cumming may not be able to draw water from the lake.[16] However, the city is looking into different sources of water such as wells and various creeks.[17]

Geography

Cumming is located in the center of Forsyth County at 34°12′30″N 84°8′15″W / 34.20833°N 84.13750°W (34.208464, -84.137575).[18] It is 39 miles (63 km) northeast of downtown Atlanta and 15 miles (24 km) northeast of Alpharetta.

According to the United States Census Bureau, Cumming has a total area of 6.1 square miles (15.9 km2), of which 6.1 square miles (15.8 km2) is land and 0.04 square miles (0.1 km2), or 0.58%, is water.[19]

Government

Cumming is a municipal corporation; since 1845 it has been governed by a mayor and a five-member city council. The mayor and council members serve staggered four-year terms.

On December 22, 1834, Cumming was officially incorporated and five councilmen were appointed: John Jolly, William Martin, Daniel McCoy, John H. Russell, and Daniel Smith. The town of Cumming's charter was revised on December 22, 1845, resulting in new councilmen William F. Foster, Arthur Irwin, Major J. Lewis, Henry L. Sims, and Noah Strong.[20]

House Bill 334 was enacted on October 10, 1885, giving Cumming a mayor and five-person city council.

Former mayor H. Ford Gravitt was first elected to the city council in 1966, and went on to be elected mayor in 1970.[21] Gravitt was mayor of Cumming for 48 years before losing to rival candidate and current mayor Troy Brumbalow, who has held the office since January 2018.[10]

City Council

| Year | Mayor | Post 1 | Post 2 | Post 3 | Post 4 | Post 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2011 | H. Ford Gravitt | Rupert Sexton | Quincy Holton | Lewis Ledbetter | Ralph Perry | John Pugh |

| 2012 | ||||||

| 2013 | ||||||

| 2014 | ||||||

| 2015 | ||||||

| 2016 | Chuck Welch | Linda Ledbetter | Christopher Light | |||

| 2017 | ||||||

| 2018 | Troy Brumbalow | Chad Crane | Jason Evans | |||

| 2019 | ||||||

| 2020 | Joey Cochran |

| City council[10] | ||

|---|---|---|

| Post | Council member | Term |

| Post 1 | Chad Crane | 2018–2021 |

| Post 2 | Jason Evans | 2018–2021 |

| Post 3 | Lewis Ledbetter | 1971–2019 |

| Post 4 | Linda Ledbetter | 2016–2019 |

| Post 5 | Christopher Light[22] | 2016–2019 |

Previous city council members

- Rupert Sexton,pro tem)[24]

- John D. Pugh,[23] 1993–2016 (Post 5)

- Quincy Holton, 1969–2017 (Post 2)[21]

- Dot Otwell,[25] 1956–1957

- Charles Welch, 1972–1986[25]

- Chuck Welch,[26] 2015–2017 (Post 1)[25]

- Ralph Perry,[24] 1979–2016 (Post 4)

- Kenneth J. Vanderhoff,[24] 1987–1990

Previous mayors

Many historical records have been destroyed in fires, leaving some information unavailable or unverifiable.[20]

- W. W. Pirkle (possible)

- T. J. Pirkle (possible)

- E. F. Smith (possible)

- Charles Leon Harris, term dates unknown (also Forsyth County School Superintendent, 1912–1916)[20]

- Alman Gwinn Hockenhull, term dates unknown (also Cumming Postmaster, 1913–1922)

- Enoch Wesley Mashburn, 1913–?

- Marcus Mashburn Sr., 1917; 1961–1966[24]

- Joseph Gaither Puett, 1918–1919[27]

- Henry Lowndes "Snacks" Patterson, 1920–1921 (also Georgia General Assembly representative, 1884–1885; Commissioner of Public Instruction, 1892–1910; Blue Ridge Circuit Court judge, 1912–1917)[20]

- John Dickerson Black, 1922–1923 (also Georgia General Assembly representative, 1933–1936)

- Andrew Benjamin "Ben" Tollison, 1926–1927 (also Forsyth County School Superintendent, 1920–1932)[20]

- Roy Pilgrim Otwell, 1928–1956; 1959–1960

- Marcus Mashburn Jr., 1957–1958

- George Ingram, 1966–1970

- H. Ford Gravitt, 1970–2018

Transportation

Major highways

Pedestrians and cycling

Demographics

| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1870 | 267 | — | |

| 1880 | 250 | −6.4% | |

| 1890 | 356 | 42.4% | |

| 1900 | 239 | −32.9% | |

| 1910 | 305 | 27.6% | |

| 1920 | 607 | 99.0% | |

| 1930 | 648 | 6.8% | |

| 1940 | 958 | 47.8% | |

| 1950 | 1,264 | 31.9% | |

| 1960 | 1,561 | 23.5% | |

| 1970 | 2,031 | 30.1% | |

| 1980 | 2,094 | 3.1% | |

| 1990 | 2,828 | 35.1% | |

| 2000 | 4,220 | 49.2% | |

| 2010 | 5,430 | 28.7% | |

| 2020 | 7,318 | 34.8% | |

| U.S. Decennial Census[28] | |||

2020 census

| Race | Num. | Perc. |

|---|---|---|

White (non-Hispanic)

|

3,999 | 54.65% |

Black or African American (non-Hispanic)

|

333 | 4.55% |

Native American

|

6 | 0.08% |

Asian

|

589 | 8.05% |

Pacific Islander

|

2 | 0.03% |

Other/Mixed

|

279 | 3.81% |

Latino

|

2,110 | 28.83% |

As of the 2020 United States census, there were 7,318 people, 2,480 households, and 1,368 families residing in the city.

2010 census

As of the

The median income for a household in the city was $37,118, and the median income for a family was $48,947. Full-time, year-round male workers had a median income of $35,402 versus $31,892 for similarly situated females. The

Education

Cumming is served by Forsyth County Schools. The following schools are located in the county school district:

Elementary schools

- Big Creek Elementary

- Brandywine Elementary

- Brookwood Elementary

- Chattahoochee Elementary

- Chestatee Elementary

- Coal Mountain Elementary

- Cumming Elementary

- Daves Creek Elementary

- Haw Creek Elementary

- Johns Creek Elementary

- Kelly Mill Elementary

- Mashburn Elementary

- Matt Elementary

- Midway Elementary

- Poole's Mill Elementary

- Sawnee Elementary

- Settles Bridge Elementary

- Sharon Elementary

- Shiloh Point Elementary

- Silver City Elementary

- Vickery Creek Elementary

- Whitlow Elementary

Middle schools

- Veritas Classical Schools

- DeSana Middle

- Hendricks Middle

- Lakeside Middle

- Liberty Middle

- Little Mill Middle

- North Forsyth Middle

- Otwell Middle

- Piney Grove Middle

- Riverwatch Middle

- South Forsyth Middle

- Vickery Creek Middle

High schools

- Alliance Academy for Innovation

- Denmark High School

- East Forsyth High School

- Forsyth Central High School

- Lambert High School

- North Forsyth High School

- Pinecrest Academy

- South Forsyth High School

- West Forsyth High School

Alternative schools

- Creative Montessori School

- Forsyth Academy

- Forsyth Virtual Academy

- Gateway Academy

- Montessori Academy at Sharon Springs

- Mountain Education

Notable people

- Luke Appling, Hall of Fame Major League Baseball player

- Zac Brown, lead singer of the Grammy Award-winning Zac Brown Band, was born in Cumming

- Col. William Cumming, distinguished officer in the War of 1812, probable eponym of the town of Cumming (incorporated 1834)

- Skyler Day, actress born in Cumming[30]

- Geoff Duncan, businessman and Lieutenant Governor of Georgia since 2019

- Kelli Giddish, actress born and raised in Cumming

- Colby Gossett, NFL player born and raised in Cumming

- Wynn Everett, actress raised in Cumming.

- Ethan Hankins, Cleveland Guardians baseball player

- season 25, born and raised in Cumming

- Tony Awardnominated actor

- Ron Reis, former World Championship Wrestling wrestler also known as The Yeti, lives in Cumming

- Junior Samples, comedian on the TV show Hee Haw

- Glenn Sutko, former catcher for the Cincinnati Reds

- Roger L. Worsley, college administrator, formerly resided in Cumming

In popular culture

- American Reunion was partially filmed in Cumming at Mary Alice Park.

- Peach State Cats, Arena Football team in Cumming, Georgia

- Unsolved Mysteries, Season 1 Episode 2 takes place in Cumming, Georgia.

- Smokey and the Bandit, Buford Dam Rd and GA400 both located in Cumming were used as filming locations.

References

- ^ "City of Cumming, Ga "Gateway to Leisure Living"". Cityofcumming.net. Archived from the original on November 23, 2010. Retrieved January 23, 2011.

- ^ "2020 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved December 18, 2021.

- ^ a b "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved May 14, 2011.

- ^ "US Board on Geographic Names". United States Geological Survey. October 25, 2007. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- ^ "Cumming (City) QuickFacts from the US Census Bureau". quickfacts.census.gov. Archived from the original on November 4, 2011. Retrieved November 20, 2011.

- ^ "Find a County". National Association of Counties. Archived from the original on May 31, 2011. Retrieved June 7, 2011.

- ^ a b c "New Georgia Encyclopedia: Cumming". Georgiaencyclopedia.org. June 22, 2006. Archived from the original on June 7, 2011. Retrieved January 23, 2011.

- ^ a b c "Cumming GA History". Cumming.com. February 1, 1956. Retrieved January 23, 2011.

- ^ "Georgia Counties by Date of Creation". Georgiainfo.galileo.usg.edu. Retrieved January 23, 2011.

- ^ a b c "Administration". City of Cumming. Retrieved July 18, 2019.

- ISBN 0-915430-00-2.

- ^ Whitmire, Kelly (January 25, 2019). "What's in a name? Historian talks about where road, area names originated in Cumming, Forsyth County". Forsyth News. Retrieved February 9, 2019.

- ^ Wait, you're from where? 11 towns and cities with suggestive names.

- ^ "1912 September and October". Rootsweb.ancestry.com. Archived from the original on January 2, 2011. Retrieved January 23, 2011.

- ^ "Memorable Guests". Oprah.com. January 1, 2006. Retrieved January 23, 2011.

- ^ Atlanta Business Chronicle - by Dave Williams (July 17, 2009). "Federal Court ruling on Lake Lanier goes against Georgia | Atlanta Business Chronicle". Bizjournals.com. Retrieved January 23, 2011.

{{cite web}}:|author=has generic name (help) - ^ "The Forsyth County News Archive". Forsythnews.com. October 8, 2010. Archived from the original on August 5, 2009. Retrieved January 23, 2011.

- ^ "US Gazetteer files: 2010, 2000, and 1990". United States Census Bureau. February 12, 2011. Retrieved April 23, 2011.

- ^ "Geographic Identifiers: 2010 Census Summary File 1 (G001), Cumming city, Georgia". American FactFinder. U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on February 13, 2020. Retrieved April 28, 2016.

- ^ a b c d e Barrett, Gladyse K. (1993). Historical Account of Cumming.

- ^ a b Estep, Tyler (November 10, 2017). "This Georgia mayor has served for 47 years. Meet the man who beat him". The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. Retrieved September 25, 2019.

- ^ Sturgeon, Kathleen (November 6, 2015). "Linda Ledbetter, Christopher Light win Cumming Council elections". North Forsyth. Retrieved September 25, 2019.

- ^ a b Torpy, Bill (January 23, 2015). "Something crazy in the water in Cumming". The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. Retrieved September 25, 2019.

- ^ a b c d "Service Delivery Strategy Manual for the City of Cumming" (PDF). May 4, 1998. Retrieved September 25, 2019.

- ^ a b c "Linda Ledbetter, Christopher Light elected to Cumming City Council". Forsyth County News. November 3, 2015. Retrieved September 25, 2019.

- ^ McNulty, Timothy J. (January 25, 1987). "Civil Rights Throng Marches in Georgia". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved September 25, 2019.

"We're just the battleground for these two forces," said Charles Welch, a member of the Cumming City Council for 14 years. He and others seemed perplexed that suddenly their county was in the glare of national attention, and they tried to analyze what it meant.

- ISBN 9780752404196.

- ^ "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- ^ "Explore Census Data". data.census.gov. Retrieved December 13, 2021.

- ^ "Skyler Day (Maggie from Gigantic) Interview!". TeenNick. November 17, 2010. Retrieved March 1, 2011.

External links

- City of Cumming official website

- Forsyth County, Georgia; Cumming is the county seat

- Video of Annual Steam Engine Parade 60 Minute DVD of parade with many antique steam engines.

- Cumming Steam, Antique Tractor and Gas Engine Exposition

- Forsyth Herald

- Cumming Historic Cemetery historical marker