Cynodont

| Cynodonts | |

|---|---|

| |

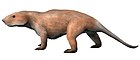

| Examples of cynodonts. 1st row: | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Synapsida |

| Clade: | Therapsida |

| Clade: | Eutheriodontia |

| Clade: | Cynodontia Owen, 1861 |

| Clades | |

Cynodonts (clade Cynodontia lit. 'dog-teeth') are

Non-mammalian cynodonts occupied a variety of

Description

Early cynodonts have many of the skeletal characteristics of

The cynodonts probably had some form of

Early cynodonts had numerous small

Derived cynodonts developed

Cynodonts are the only known synapsid lineage to have produced aerial locomotors, with gliding and flying being known in haramiyidans[10] and various mammal groups.

The largest known non-mammalian cynodont is

Evolutionary history

The closest relatives of cynodonts are therocephalians, with which they form the clade Eutheriodontia.[12]

The earliest cynodonts are known early Lopingian (early Wuchiapingian) aged sediments of the Tropidostoma Assemblage Zone, in the Karoo Supergroup of South Africa, belonging to the basal family Charassognathidae. Fossils of Permian cynodonts are relatively rare outside of South Africa, with the most widely distributed genus being Procynosuchus, which is known from South Africa, Germany, Tanzania, Zambia, and possibly Russia.[13]

Cynodonts expanded rapidly in diversity after the Permian-Triassic extinction event. Peak disparity in cynodonts occurred from the Induan to the Carnian and in the middle Norian.[14] Post-Early Triassic cynodonts were dominated by members of the advanced clade Eucynodontia, which has two main subdivisions, the predominantly herbivorous Cynognathia and the predominantly carnivorous Probainognathia. During the Early and Middle Triassic, cynodont diversity was dominated by members of Cynognathia, and members of Probainognathia would not become prominent until the Late Triassic (early Norian).[15] Almost all Middle Triassic cynodonts are known from Gondwana, with only one genus (Nanogomphodon) having been found in the Northern Hemisphere. Among the most dominant groups of Middle and Late Triassic cynodonts is the herbivorous Traversodontidae, predominantly in Gondwana, which reached a peak diversity in the Late Triassic. Mammaliaformes originated from probainognathian cynodonts during the Late Triassic.[16] Early Mammaliaformes were small bodied insectivores.[17] Only two groups of non-mammaliaform cynodonts existed beyond the end of the Triassic, both belonging to Probainognathia. The first is the insectivorous Tritheledontidae, which briefly lasted into the Early Jurassic. The second is the herbivorous Tritylodontidae, which first appeared in the latest Triassic, which were abundant and diverse during the Jurassic, predominantly in the Northern Hemisphere, persisted into the Early Cretaceous (Barremian-Aptian) in Asia, at least until around 120 million years ago, as represented by Fossiomanus from China.[16][18]

During their

Cynodonts also developed a secondary palate in the roof of the mouth. This caused air flow from the nostrils to travel to a position in the back of the mouth instead of directly through it, allowing cynodonts to chew and breathe at the same time. This characteristic is present in all mammals.

Taxonomy

Phylogeny

Below is a cladogram from Ruta, Botha-Brink, Mitchell and Benton (2013) showing one hypothesis of cynodont relationships:[15]

Cynodontia

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Distribution

Non-mammalian cynodonts have been found in South America, India, Africa, Antarctica,[23] Asia,[24] Europe[25] and North America.[26]

See also

- Permian–Triassic extinction event

- Prehistoric mammal

- Tetrapod

- Triassic-Jurassic extinction event

References

- .

- .

- ^ Estes, Richard (1961). "Cranial anatomy of the cynodont reptile Thrinaxodon liorhinus". Bulletin of the Museum of Comparative Zoology. 125: 165–180.

- PMID 27157809.

- S2CID 254702274.

- S2CID 4318400.

- ^ Michael L. Power, Jay Schulkin. The Evolution of the Human Placenta. pp. 68–.

- ^ Jason A. Lillegraven, Zofia Kielan-Jaworowska, William A. Clemens, Mesozoic Mammals: The First Two-Thirds of Mammalian History, University of California Press, 17 December 1979 – 321

- S2CID 205570021.

- S2CID 205259206.

- S2CID 237517965.

- S2CID 92370138.

- S2CID 228883951.

- PMID 23986112.

- ^ PMID 23986112.

- ^ ISBN 978-3-319-68008-8, retrieved 24 May 2021

- S2CID 195327500.

- S2CID 233183060.

- ^ Classification of R. Owen 1861.

- ^ Classification of B. S. Rubidge and C. A. Sidor 2001

- ^ R. Broom. 1913. A revision of the reptiles of the Karroo. Annals of the South African Museum 7(6):361–366

- ^ S. H. Haughton and A. S. Brink. 1954. A bibliographical list of Reptilia from the Karroo Beds of South Africa. Palaeontologia Africana 2:1–187

- .

- ISBN 0-231-08482-X. Retrieved 30 November 2019.

- ^ Fraser, Nicholas C.; Sues, Hans-Dieter (1997). In the Shadow of the Dinosaurs: Early Mesozoic Tetrapods. Cambridge University Press.

- ]

Further reading

- Hopson, J.A.; Kitching, J.W. (2001). "A probainognathian cynodont from South Africa and the phylogeny of non-mammalian cynodonts". Bull. Mus. Comp. Zool. 156: 5–35.

- Davis, Dwight (1961). "Origin of the Mammalian Feeding Mechanism". Am. Zoologist, 1:229–234.