Cytosol

Animal cell diagram | |

|---|---|

Components of a typical animal cell:

|

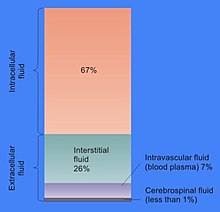

The cytosol, also known as cytoplasmic matrix or groundplasm,[2] is one of the liquids found inside cells (intracellular fluid (ICF)).[3] It is separated into compartments by membranes. For example, the mitochondrial matrix separates the mitochondrion into many compartments.

In the

The cytosol is a complex mixture of substances dissolved in water. Although water forms the large majority of the cytosol, its structure and properties within cells is not well understood. The concentrations of

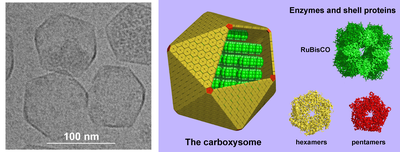

Although it was once thought to be a simple solution of molecules, the cytosol has multiple levels of organization. These include concentration gradients of small molecules such as calcium, large complexes of enzymes that act together and take part in metabolic pathways, and protein complexes such as proteasomes and carboxysomes that enclose and separate parts of the cytosol.

Definition

The term "cytosol" was first introduced in 1965 by H. A. Lardy, and initially referred to the liquid that was produced by breaking cells apart and pelleting all the insoluble components by ultracentrifugation.[4][5] Such a soluble cell extract is not identical to the soluble part of the cell cytoplasm and is usually called a cytoplasmic fraction.[6]

The term cytosol is now used to refer to the liquid phase of the cytoplasm in an intact cell.[6] This excludes any part of the cytoplasm that is contained within organelles.[7] Due to the possibility of confusion between the use of the word "cytosol" to refer to both extracts of cells and the soluble part of the cytoplasm in intact cells, the phrase "aqueous cytoplasm" has been used to describe the liquid contents of the cytoplasm of living cells.[5]

Prior to this, other terms, including hyaloplasm,[8] were used for the cell fluid, not always synonymously, as its nature was not well understood (see protoplasm).[6]

Properties and composition

The proportion of cell volume that is cytosol varies: for example while this compartment forms the bulk of cell structure in

Water

Most of the cytosol is water, which makes up about 70% of the total volume of a typical cell.[15] The pH of the intracellular fluid is 7.4.[16] while human cytosolic pH ranges between 7.0–7.4, and is usually higher if a cell is growing.[17] The viscosity of cytoplasm is roughly the same as pure water, although diffusion of small molecules through this liquid is about fourfold slower than in pure water, due mostly to collisions with the large numbers of macromolecules in the cytosol.[18] Studies in the brine shrimp have examined how water affects cell functions; these saw that a 20% reduction in the amount of water in a cell inhibits metabolism, with metabolism decreasing progressively as the cell dries out and all metabolic activity halting when the water level reaches 70% below normal.[5]

Although water is vital for life, the structure of this water in the cytosol is not well understood, mostly because methods such as nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy only give information on the average structure of water, and cannot measure local variations at the microscopic scale. Even the structure of pure water is poorly understood, due to the ability of water to form structures such as water clusters through hydrogen bonds.[19]

The classic view of water in cells is that about 5% of this water is strongly bound in by solutes or macromolecules as water of solvation, while the majority has the same structure as pure water.[5] This water of solvation is not active in osmosis and may have different solvent properties, so that some dissolved molecules are excluded, while others become concentrated.[20][21] However, others argue that the effects of the high concentrations of macromolecules in cells extend throughout the cytosol and that water in cells behaves very differently from the water in dilute solutions.[22] These ideas include the proposal that cells contain zones of low and high-density water, which could have widespread effects on the structures and functions of the other parts of the cell.[19][23] However, the use of advanced nuclear magnetic resonance methods to directly measure the mobility of water in living cells contradicts this idea, as it suggests that 85% of cell water acts like that pure water, while the remainder is less mobile and probably bound to macromolecules.[24]

Ions

The concentrations of the other ions in cytosol are quite different from those in extracellular fluid and the cytosol also contains much higher amounts of charged macromolecules such as proteins and nucleic acids than the outside of the cell structure.

| Ion | Concentration (millimolar) | |

|---|---|---|

| In cytosol | In plasma | |

| Potassium | 139–150[25][26] | 4 |

| Sodium | 12 | 145 |

| Chloride | 4 | 116 |

| Bicarbonate | 12 | 29 |

| Amino acids in proteins | 138 | 9 |

| Magnesium | 0.8 | 1.5 |

| Calcium | <0.0002 | 1.8 |

In contrast to extracellular fluid, cytosol has a high concentration of

Cells can deal with even larger osmotic changes by accumulating

The low concentration of

Macromolecules

Protein molecules that do not bind to

In prokaryotes the cytosol contains the cell's

This high concentration of macromolecules in cytosol causes an effect called

Organization

Although the components of the cytosol are not separated into regions by cell membranes, these components do not always mix randomly and several levels of organization can localize specific molecules to defined sites within the cytosol.[38]

Concentration gradients

Although small molecules diffuse rapidly in the cytosol, concentration gradients can still be produced within this compartment. A well-studied example of these are the "calcium sparks" that are produced for a short period in the region around an open calcium channel.[39] These are about 2 micrometres in diameter and last for only a few milliseconds, although several sparks can merge to form larger gradients, called "calcium waves".[40] Concentration gradients of other small molecules, such as oxygen and adenosine triphosphate may be produced in cells around clusters of mitochondria, although these are less well understood.[41][42]

Protein complexes

Proteins can associate to form

Protein compartments

Some protein complexes contain a large central cavity that is isolated from the remainder of the cytosol. One example of such an enclosed compartment is the proteasome.[48] Here, a set of subunits form a hollow barrel containing proteases that degrade cytosolic proteins. Since these would be damaging if they mixed freely with the remainder of the cytosol, the barrel is capped by a set of regulatory proteins that recognize proteins with a signal directing them for degradation (a ubiquitin tag) and feed them into the proteolytic cavity.[49]

Another large class of protein compartments are

Biomolecular condensates

Non-membrane bound organelles can form as

Cytoskeletal sieving

Although the cytoskeleton is not part of the cytosol, the presence of this network of filaments restricts the diffusion of large particles in the cell. For example, in several studies tracer particles larger than about 25 nanometres (about the size of a ribosome)[53] were excluded from parts of the cytosol around the edges of the cell and next to the nucleus.[54][55] These "excluding compartments" may contain a much denser meshwork of actin fibres than the remainder of the cytosol. These microdomains could influence the distribution of large structures such as ribosomes and organelles within the cytosol by excluding them from some areas and concentrating them in others.[56]

Function

The cytosol is the site of multiple cell processes. Examples of these processes include

The cytosol is the site of most metabolism in prokaryotes,[9] and a large proportion of the metabolism of eukaryotes. For instance, in mammals about half of the proteins in the cell are localized to the cytosol.[64] The most complete data are available in yeast, where metabolic reconstructions indicate that the majority of both metabolic processes and metabolites occur in the cytosol.[65] Major metabolic pathways that occur in the cytosol in animals are protein biosynthesis, the pentose phosphate pathway, glycolysis and gluconeogenesis.[66] The localization of pathways can be different in other organisms, for instance fatty acid synthesis occurs in chloroplasts in plants[67][68] and in apicoplasts in apicomplexa.[69]

References

- ^ PMID 11590012.

- ISBN 9780198529170.

- ^ Liachovitzky, Carlos (2015). "Human Anatomy and Physiology Preparatory Course" (pdf). Open Educational Resources. CUNY Academic Works: 69. Archived from the original on 2017-08-23. Retrieved 2021-06-22.

- ^ Lardry, H. A. 1969. On the direction of pyridine nucleotide oxidation-reduction reactions in gluconeogenesis and lipogenesis. In: Control of energy metabolism, edited by B. Chance, R. Estabrook, and J. R. Williamson. New York: Academic, 1965, p. 245, [1].

- ^ S2CID 30351411.

- ^ OCLC 225587597.

- ^ OCLC 174431482.

- ^ Hanstein, J. (1880). Das Protoplasma. Heidelberg. p. 24.

- ^ S2CID 21004307.

- PMID 11373301.

- PMID 15109811. Archived from the original(PDF) on 2008-12-17.

- S2CID 1197884.

- PMID 12952533.

- PMID 12566402.

- PMID 10553280. Archived from the original(PDF) on 2011-07-19.

- PMID 7012859.

- PMID 3558476.

- ^ PMID 11796221.

- ^ PMID 2087221.

- S2CID 6370250.

- PMID 10553283.

- S2CID 42919563.

- S2CID 42866068.

- PMID 18436650.

- PMID 3706350.

- ^ Lote, Christopher J. (2012). Principles of Renal Physiology, 5th edition. Springer. p. 12.

- ^ S2CID 1798009.

- PMID 11513823.

- PMID 9558455.

- PMID 9080360.

- PMID 2549852.

- S2CID 26068558.

- PMID 14645541.

- S2CID 45792524.

- S2CID 25355087.

- PMID 16739728.

- PMID 18573087.

- PMID 17347523.

- PMID 15117829.

- PMID 8131190.

- PMID 10553281.

- PMID 11463714.

- PMID 2441660.

- PMID 10966480.

- S2CID 16722363.

- PMID 133800.

- PMID 3775377.

- PMID 14675543.

- (PDF) from the original on 2006-07-02.

- ^ Bobik, T. A. (2007). "Bacterial Microcompartments" (PDF). Microbe. 2. Am Soc Microbiol: 25–31. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-08-02.

- S2CID 22666203.

- PMID 12554704.

- PMID 11860284.

- PMID 7980739.

- PMID 3474634.

- S2CID 12063324.

- S2CID 18002214.

- PMID 17719262.

- PMID 7790357.

- S2CID 9608133.

- PMID 16709155.

- PMID 10515003.

- PMID 11792546.

- S2CID 32197.

- PMID 18846089.

- OCLC 179705944.

- PMID 11171129.

- PMID 286305.

- S2CID 2565225.

Further reading

- Wheatley, Denys N.; Pollack, Gerald H.; Cameron, Ivan L. (2006). Water and the Cell. Berlin: Springer. OCLC 71298997.