DNA nanotechnology

| Part of a series of articles on |

| Molecular self-assembly |

|---|

|

DNA nanotechnology is the design and manufacture of artificial

The conceptual foundation for DNA nanotechnology was first laid out by

History

The conceptual foundation for DNA nanotechnology was first laid out by

In 1991, Seeman's laboratory published a report on the synthesis of a cube made of DNA, the first synthetic three-dimensional nucleic acid nanostructure, for which he received the 1995

New abilities continued to be discovered for designed DNA structures throughout the 2000s. The first DNA nanomachine—a motif that changes its structure in response to an input—was demonstrated in 1999 by Seeman. An improved system, which was the first nucleic acid device to make use of toehold-mediated strand displacement, was demonstrated by Bernard Yurke in 2000.[9] The next advance was to translate this into mechanical motion, and in 2004 and 2005, several DNA walker systems were demonstrated by the groups of Seeman, Niles Pierce, Andrew Turberfield, and Chengde Mao.[10] The idea of using DNA arrays to template the assembly of other molecules such as nanoparticles and proteins, first suggested by Bruche Robinson and Seeman in 1987,[11] was demonstrated in 2002 by Seeman, Kiehl et al.[12] and subsequently by many other groups.

In 2006, Rothemund first demonstrated the DNA origami method for easily and robustly forming folded DNA structures of arbitrary shape. Rothemund had conceived of this method as being conceptually intermediate between Seeman's DX lattices, which used many short strands, and William Shih's DNA octahedron, which consisted mostly of one very long strand. Rothemund's DNA origami contains a long strand which folding is assisted by several short strands. This method allowed forming much larger structures than formerly possible, and which are less technically demanding to design and synthesize.[7] DNA origami was the cover story of Nature on March 15, 2006.[13] Rothemund's research demonstrating two-dimensional DNA origami structures was followed by the demonstration of solid three-dimensional DNA origami by Douglas et al. in 2009,[14] while the labs of Jørgen Kjems and Yan demonstrated hollow three-dimensional structures made out of two-dimensional faces.[8]

DNA nanotechnology was initially met with some skepticism due to the unusual non-biological use of nucleic acids as materials for building structures and doing computation, and the preponderance of

Fundamental concepts

Properties of nucleic acids

The structure of a nucleic acid molecule consists of a sequence of nucleotides distinguished by which nucleobase they contain. In DNA, the four bases present are adenine (A), cytosine (C), guanine (G), and thymine (T). Nucleic acids have the property that two molecules will only bind to each other to form a double helix if the two sequences are complementary, meaning that they form matching sequences of base pairs, with A only binding to T, and C only to G.[5][20] Because the formation of correctly matched base pairs is energetically favorable, nucleic acid strands are expected in most cases to bind to each other in the conformation that maximizes the number of correctly paired bases. The sequences of bases in a system of strands thus determine the pattern of binding and the overall structure in an easily controllable way. In DNA nanotechnology, the base sequences of strands are rationally designed by researchers so that the base pairing interactions cause the strands to assemble in the desired conformation.[3][5] While DNA is the dominant material used, structures incorporating other nucleic acids such as RNA and peptide nucleic acid (PNA) have also been constructed.[21][22]

Subfields

DNA nanotechnology is sometimes divided into two overlapping subfields: structural DNA nanotechnology and dynamic DNA nanotechnology. Structural DNA nanotechnology, sometimes abbreviated as SDN, focuses on synthesizing and characterizing nucleic acid complexes and materials that assemble into a static, equilibrium end state. On the other hand, dynamic DNA nanotechnology focuses on complexes with useful non-equilibrium behavior such as the ability to reconfigure based on a chemical or physical stimulus. Some complexes, such as nucleic acid nanomechanical devices, combine features of both the structural and dynamic subfields.[23][24]

The complexes constructed in structural DNA nanotechnology use topologically branched nucleic acid structures containing junctions. (In contrast, most biological DNA exists as an unbranched double helix.) One of the simplest branched structures is a four-arm junction that consists of four individual DNA strands, portions of which are complementary in a specific pattern. Unlike in natural Holliday junctions, each arm in the artificial immobile four-arm junction has a different base sequence, causing the junction point to be fixed at a certain position. Multiple junctions can be combined in the same complex, such as in the widely used double-crossover (DX) structural motif, which contains two parallel double helical domains with individual strands crossing between the domains at two crossover points. Each crossover point is, topologically, a four-arm junction, but is constrained to one orientation, in contrast to the flexible single four-arm junction, providing a rigidity that makes the DX motif suitable as a structural building block for larger DNA complexes.[3][5]

Dynamic DNA nanotechnology uses a mechanism called

Structural DNA nanotechnology

Structural DNA nanotechnology, sometimes abbreviated as SDN, focuses on synthesizing and characterizing nucleic acid complexes and materials where the assembly has a static, equilibrium endpoint. The nucleic acid double helix has a robust, defined three-dimensional geometry that makes it possible to simulate,[26] predict and design the structures of more complicated nucleic acid complexes. Many such structures have been created, including two- and three-dimensional structures, and periodic, aperiodic, and discrete structures.[24]

Extended lattices

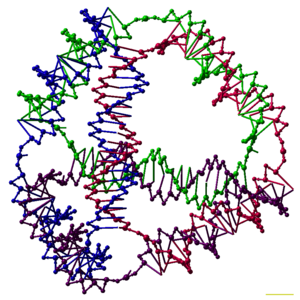

Small nucleic acid complexes can be equipped with

Two-dimensional arrays can be made to exhibit aperiodic structures whose assembly implements a specific algorithm, exhibiting one form of DNA computing.

DX arrays have been made to form hollow nanotubes 4–20

Forming three-dimensional lattices of DNA was the earliest goal of DNA nanotechnology, but this proved to be one of the most difficult to realize. Success using a motif based on the concept of tensegrity, a balance between tension and compression forces, was finally reported in 2009.[17][39]

Discrete structures

Researchers have synthesized many three-dimensional DNA complexes that each have the connectivity of a polyhedron, such as a cube or octahedron, meaning that the DNA duplexes trace the edges of a polyhedron with a DNA junction at each vertex.[6] The earliest demonstrations of DNA polyhedra were very work-intensive, requiring multiple ligations and solid-phase synthesis steps to create catenated polyhedra.[40] Subsequent work yielded polyhedra whose synthesis was much easier. These include a DNA octahedron made from a long single strand designed to fold into the correct conformation,[41] and a tetrahedron that can be produced from four DNA strands in one step, pictured at the top of this article.[1]

Nanostructures of arbitrary, non-regular shapes are usually made using the DNA origami method. These structures consist of a long, natural virus strand as a "scaffold", which is made to fold into the desired shape by computationally designed short "staple" strands. This method has the advantages of being easy to design, as the base sequence is predetermined by the scaffold strand sequence, and not requiring high strand purity and accurate stoichiometry, as most other DNA nanotechnology methods do. DNA origami was first demonstrated for two-dimensional shapes, such as a smiley face, a coarse map of the Western Hemisphere, and the Mona Lisa painting.[6][13][42] Solid three-dimensional structures can be made by using parallel DNA helices arranged in a honeycomb pattern,[14] and structures with two-dimensional faces can be made to fold into a hollow overall three-dimensional shape, akin to a cardboard box. These can be programmed to open and reveal or release a molecular cargo in response to a stimulus, making them potentially useful as programmable molecular cages.[43][44]

Templated assembly

Nucleic acid structures can be made to incorporate molecules other than nucleic acids, sometimes called heteroelements, including proteins, metallic nanoparticles, quantum dots, amines,[45] and fullerenes. This allows the construction of materials and devices with a range of functionalities much greater than is possible with nucleic acids alone. The goal is to use the self-assembly of the nucleic acid structures to template the assembly of the nanoparticles hosted on them, controlling their position and in some cases orientation.[6][46] Many of these schemes use a covalent attachment scheme, using oligonucleotides with

Dynamic DNA nanotechnology

Dynamic DNA nanotechnology focuses on forming nucleic acid systems with designed dynamic functionalities related to their overall structures, such as computation and mechanical motion. There is some overlap between structural and dynamic DNA nanotechnology, as structures can be formed through annealing and then reconfigured dynamically, or can be made to form dynamically in the first place.[6][10]

Nanomechanical devices

DNA complexes have been made that change their conformation upon some stimulus, making them one form of

DNA walkers are a class of nucleic acid nanomachines that exhibit directional motion along a linear track. A large number of schemes have been demonstrated.[10] One strategy is to control the motion of the walker along the track using control strands that need to be manually added in sequence.[60][61] It is also possible to control individual steps of a DNA walker by irradiation with light of different wavelengths.[62] Another approach is to make use of restriction enzymes or deoxyribozymes to cleave the strands and cause the walker to move forward, which has the advantage of running autonomously.[63][64] A later system could walk upon a two-dimensional surface rather than a linear track, and demonstrated the ability to selectively pick up and move molecular cargo.[65] In 2018, a catenated DNA that uses rolling circle transcription by an attached T7 RNA polymerase was shown to walk along a DNA-path, guided by the generated RNA strand.[66] Additionally, a linear walker has been demonstrated that performs DNA-templated synthesis as the walker advances along the track, allowing autonomous multistep chemical synthesis directed by the walker.[67] The synthetic DNA walkers' function is similar to that of the proteins dynein and kinesin.[68]

Strand displacement cascades

Cascades of strand displacement reactions can be used for either computational or structural purposes. An individual strand displacement reaction involves revealing a new sequence in response to the presence of some initiator strand. Many such reactions can be linked into a cascade where the newly revealed output sequence of one reaction can initiate another strand displacement reaction elsewhere. This in turn allows for the construction of chemical reaction networks with many components, exhibiting complex computational and information processing abilities. These cascades are made energetically favorable through the formation of new base pairs, and the entropy gain from disassembly reactions. Strand displacement cascades allow isothermal operation of the assembly or computational process, in contrast to traditional nucleic acid assembly's requirement for a thermal annealing step, where the temperature is raised and then slowly lowered to ensure proper formation of the desired structure. They can also support catalytic function of the initiator species, where less than one equivalent of the initiator can cause the reaction to go to completion.[23][69]

Strand displacement complexes can be used to make

Another use of strand displacement cascades is to make dynamically assembled structures. These use a hairpin structure for the reactants, so that when the input strand binds, the newly revealed sequence is on the same molecule rather than disassembling. This allows new opened hairpins to be added to a growing complex. This approach has been used to make simple structures such as three- and four-arm junctions and dendrimers.[69]

Applications

DNA nanotechnology provides one of the few ways to form designed, complex structures with precise control over nanoscale features. The field is beginning to see application to solve

DNA nanotechnology is moving toward potential real-world applications. The ability of nucleic acid arrays to arrange other molecules indicates its potential applications in molecular scale electronics. The assembly of a nucleic acid structure could be used to template the assembly of molecular electronic elements such as molecular wires, providing a method for nanometer-scale control of the placement and overall architecture of the device analogous to a molecular breadboard.[24][6] DNA nanotechnology has been compared to the concept of programmable matter because of the coupling of computation to its material properties.[73]

In a study conducted by a group of scientists from iNANO and CDNA centers in Aarhus University, researchers were able to construct a small multi-switchable 3D DNA Box Origami. The proposed nanoparticle was characterized by atomic force microscopy (AFM), transmission electron microscopy (TEM) and Förster resonance energy transfer (FRET). The constructed box was shown to have a unique reclosing mechanism, which enabled it to repeatedly open and close in response to a unique set of DNA or RNA keys. The authors proposed that this "DNA device can potentially be used for a broad range of applications such as controlling the function of single molecules, controlled drug delivery, and molecular computing."[74]

There are potential applications for DNA nanotechnology in nanomedicine, making use of its ability to perform computation in a

Applications for DNA nanotechnology in nanomedicine also focus on mimicking the structure and function of naturally occurring

Design

DNA nanostructures must be

Structural design

The first step in designing a nucleic acid nanostructure is to decide how a given structure should be represented by a specific arrangement of nucleic acid strands. This design step determines the secondary structure, or the positions of the base pairs that hold the individual strands together in the desired shape.[36] Several approaches have been demonstrated:

- Tile-based structures. This approach breaks the target structure into smaller units with strong binding between the strands contained in each unit, and weaker interactions between the units. It is often used to make periodic lattices, but can also be used to implement algorithmic self-assembly, making them a platform for DNA computing. This was the dominant design strategy used from the mid-1990s until the mid-2000s, when the DNA origami methodology was developed.[36][92]

- Folding structures. An alternative to the tile-based approach, folding approaches make the nanostructure from one long strand, which can either have a designed sequence that folds due to its interactions with itself, or it can be folded into the desired shape by using shorter, "staple" strands. This latter method is called DNA origami, which allows forming nanoscale two- and three-dimensional shapes (see Discrete structures above).[6][13]

- Dynamic assembly. This approach directly controls the

Sequence design

After any of the above approaches are used to design the secondary structure of a target complex, an actual sequence of nucleotides that will form into the desired structure must be devised. Nucleic acid design is the process of assigning a specific nucleic acid base sequence to each of a structure's constituent strands so that they will associate into a desired conformation. Most methods have the goal of designing sequences so that the target structure has the lowest

Nucleic acid design has similar goals to protein design. In both, the sequence of monomers is designed to favor the desired target structure and to disfavor other structures. Nucleic acid design has the advantage of being much computationally easier than protein design, because the simple base pairing rules are sufficient to predict a structure's energetic favorability, and detailed information about the overall three-dimensional folding of the structure is not required. This allows the use of simple heuristic methods that yield experimentally robust designs. Nucleic acid structures are less versatile than proteins in their function because of proteins' increased ability to fold into complex structures, and the limited chemical diversity of the four nucleotides as compared to the twenty proteinogenic amino acids.[93]

Materials and methods

The sequences of the DNA strands making up a target structure are designed computationally, using

The fully formed target structures can be verified using

Nucleic acid structures can be directly imaged by

See also

- International Society for Nanoscale Science, Computation, and Engineering

- Comparison of nucleic acid simulation software

- Molecular models of DNA

- Nanobiotechnology

References

- ^ S2CID 13678773.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-58488-687-7.

- ^ PMID 15195395.

- ^ History: See "Current crystallization protocol". Nadrian Seeman Lab. for a statement of the problem, and "DNA cages containing oriented guests". Nadrian Seeman Laboratory. for the proposed solution.

- ^ PMID 20222824.

- ^ PMID 22056726.

- ^ ISBN 978-3-540-30295-7.

- ^ PMID 21636754.

- S2CID 2064216.

- ^ PMID 18654284.

- PMID 3508280.

- S2CID 2257083.

- ^ S2CID 4316391.

- ^ PMID 19458720.

- PMID 21636754.

- ^ History: Hopkin K (August 2011). "Profile: 3-D seer". The Scientist. Archived from the original on 10 October 2011. Retrieved 8 August 2011.

- ^ PMID 20486672.

- ^ PMID 15597116.

- ISBN 978-1-58488-687-7.

- ISBN 978-0-19-508467-2.

- S2CID 9296608.

- PMID 21102465.

- ^ PMID 21258382.

- ^ PMID 17952671.

- PMID 17056247.

- S2CID 15324396.

- PMID 15024422.

- S2CID 137635908.

- ^ PMID 15583715.

- S2CID 4385579.

- .

- .

- PMID 17036134.

- PMID 15826105.

- PMID 16351220.

- ^ PMID 16470892.

- PMID 15600335.

- S2CID 12100380.

- PMID 19727196.

- .

- S2CID 4419579.

- S2CID 4455780.

- ^ S2CID 4430815.

- PMID 19419184.

- S2CID 246946068.

- S2CID 205554125.

- PMID 16834438.

- PMID 16374784.

- PMID 17763481.

- PMID 19898497.

- PMID 21323323.

- PMID 15300697.

- S2CID 4406177.

- S2CID 2064216.

- S2CID 52801697.

- PMID 14502706.

- PMID 18654468.

- S2CID 9866509.

- PMID 37857824.

- PMID 15339155.

- .

- S2CID 85446523.

- PMID 15945114.

- PMID 15959864.

- PMID 20463735.

- PMID 29632399.

- PMID 20935654.

- PMID 25498478.

- ^ S2CID 4354536.

- PMID 25565140.

- S2CID 10966324.

- S2CID 10053541.

- ISBN 978-0-387-98988-4. Retrieved 17 April 2011.

- PMID 23030709.

- PMID 19404476.

- ^ Lovy, Howard (5 July 2011). "DNA cages can unleash meds inside cells". fiercedrugdelivery.com. Retrieved 22 September 2013.[permanent dead link]

- PMID 21696187.

- ^ Trafton, Anne (4 June 2012). "Researchers achieve RNA interference, in a lighter package". MIT News. Retrieved 22 September 2013.

- PMID 22659608.

- PMID 23380739.

- S2CID 195825879.

- PMID 23161995.

- ^ PMID 27324157.

- PMID 23611515.

- PMID 24014236.

- PMID 25338165.

- PMID 25816075.

- PMID 26751170.

- PMID 27504755.

- PMID 29930243.

- ^ .

- PMID 16832805.

- ^ PMID 14990744.

- S2CID 205152989.

- S2CID 27187583.

- S2CID 94329398.

- S2CID 43406338.

- S2CID 9978415.

- PMID 21674361.

- ISBN 978-0-935702-49-1.

Further reading

General:

- Seeman NC (June 2004). "Nanotechnology and the double helix". Scientific American. 290 (6): 64–75. PMID 15195395.—An article written for laypeople by the founder of the field

- Seeman NC (June 2010). "Structural DNA nanotechnology: growing along with Nano Letters". Nano Letters. 10 (6): 1971–1978. PMID 20486672.—A review of results in the period 2001–2010

- Seeman NC (2010). "Nanomaterials based on DNA". Annual Review of Biochemistry. 79: 65–87. PMID 20222824.—A more comprehensive review including both old and new results in the field

- Service RF (June 2011). "DNA nanotechnology. DNA nanotechnology grows up". Science. 332 (6034): 1140–1, 1143. PMID 21636755..—A news article focusing on the history of the field and development of new applications

- Zadegan RM, Norton ML (June 2012). "Structural DNA nanotechnology: from design to applications". International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 13 (6): 7149–7162. PMID 22837684.—A very recent and comprehensive review in the field

Specific subfields:

- Bath J, Turberfield AJ (May 2007). "DNA nanomachines". Nature Nanotechnology. 2 (5): 275–284. PMID 18654284.—A review of nucleic acid nanomechanical devices

- Feldkamp U, Niemeyer CM (March 2006). "Rational design of DNA nanoarchitectures". Angewandte Chemie. 45 (12): 1856–1876. PMID 16470892.—A review coming from the viewpoint of secondary structure design

- Lin C, Liu Y, Rinker S, Yan H (August 2006). "DNA tile based self-assembly: building complex nanoarchitectures". ChemPhysChem. 7 (8): 1641–1647. PMID 16832805.—A minireview specifically focusing on tile-based assembly

- Zhang DY, Seelig G (February 2011). "Dynamic DNA nanotechnology using strand-displacement reactions". Nature Chemistry. 3 (2): 103–113. PMID 21258382.—A review of DNA systems making use of strand displacement mechanisms

External links

- What is Bionanotechnology?—a video introduction to DNA nanotechnology