Daniel De Leon

Daniel De Leon | |

|---|---|

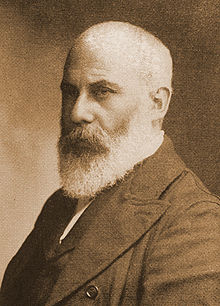

De Leon in 1902 | |

| Born | December 14, 1852 |

| Died | May 11, 1914 (aged 61) |

| Nationality |

|

| Other names | Daniel de León |

| Alma mater | |

| Occupations |

|

| Organizations | |

| Known for | Marxism–De Leonism |

| Height | 5 ft 5 in (165 cm)[1] |

| Political party | Socialist Labor Party |

| Movement | American Labor Movement |

| Spouses |

Bertha Canary (m. 1892) |

| Children | 9, including Solon |

| This article is part of a series on |

| Socialism in the United States |

|---|

| Part of the Politics series on |

| De Leonism |

|---|

|

| Daniel De Leon |

| Marxism |

| Concepts |

|

| DeLeonists |

| Organizations |

| Socialism portal |

| Part of a series on |

| Left communism |

|---|

|

Daniel De Leon (

Biography

Early life and academic career

Daniel De Leon was born December 14, 1852, in Curaçao, the son of Salomon de Leon and Sarah Jesurun De Leon. His father was a surgeon in the Royal Netherlands Army and a colonial official. Although he was raised Catholic, his family ancestry is believed to be Dutch Jewish of the Spanish and Portuguese community; "De León" is a Spanish surname, oftentimes toponymic, in which case it can possibly indicate a family's geographic origin in the Medieval Kingdom of León.

His father lived in the Netherlands before coming to Curaçao when receiving his commission in the military. Salomon De Leon died on January 18, 1865, when Daniel was twelve and was the first to be buried in the new Jewish cemetery.[3]

De Leon left Curaçao on April 15, 1866, and arrived in

From 1878 to 1882, he lived in Brownsville, Texas, as a practicing attorney, then returned to New York. While he maintained an attorney's office until 1884 he was more interested in pursuing an academic career at his alma mater, Columbia. A prize lectureship had been created in 1882. To be eligible a candidate had to be a graduate of Columbia, a member of the Academy of Political Science and read at least one paper before the academy. The three year appointment came with a $500 annual salary ($16,000 in 2024 terms) and required the lecturer to give twenty lectures a year, based on original research, to the students of the School of Political Science. De Leon devoted his lectures to Latin American diplomacy and the interventions of European powers in South American affairs. He received his first term in 1883 and his second term in 1886. In 1889 he was not kept on. Some allege that the University officials denied him a promised full professorship because of his political activities,[7] while other believe that his subject was too esoteric to be a permanent part of the curriculum.[8]

De Leon published no papers about Latin America during this period, but he did contribute an article to the debut issue of the Academy's

Personal life

De Leon traveled back to Curaçao to marry the 16-year-old Sarah Lobo from

In 1891, while on a speaking tour around the country for the SLP, De Leon found himself in Kansas when he learned that a planned speaking engagement in

Political career

De Leon settled in New York City, studying at

De Leon became a

De Leon was highly critical of the trade union movement in America and described the craft-oriented American Federation of Labor as the "American Separation of Labor". At this early stage in De Leon's development, there was still a considerable remnant of the general unionist Knights of Labor in existence, and the SLP worked within it until being driven out. This resulted in the formation of the Socialist Trade and Labor Alliance (ST&LA) in 1895, which was dominated by the SLP.

By the early 20th Century, the SLP was declining in numbers, with first the

De Leon later accused the IWW of having been taken over by what he called disparagingly 'the bummery'. De Leon was engaged in a policy dispute with the leaders of the IWW. His argument was in support of political action via the Socialist Labor Party while other leaders, including founder

Death and legacy

De Leon was formally expelled from the Chicago IWW after calling proponents of that organization "slum proletarians".[15] His Socialist Labor Party has remained influential, largely by keeping his ideas alive.

De Leon died on May 11, 1914, of Septic Endocarditis at Mount Sinai Hospital in Manhattan, New York.[16]

Daniel De Leon proved hugely influential to other socialists, also outside the US. For example, in the UK, a

Electoral history

De Leon ran in

Works

- Reform or Revolution?, speech, 1896.

- What Means This Strike?, speech, 1898.

- Socialism vs Anarchism, speech, 1901.

- The Mysteries of the People, a series of 19 novels translated from Eugène Sue's text, 1904.

- Two Pages from Roman History

- The Burning Question of Trade Unionism

- Preamble of the IWW, later renamed The Socialist Reconstruction of Society.

- DeLeon Replies ... (short essay, 1904)

Notes

Notes

- Dutch colony, he was Dutchby birth and became a naturalized American.

Citations

- ^ Reeve op cit. p. 6

- ^ Kenneth T. Jackson, ed. (1995-09-26). "DeLeon, Daniel". The Encyclopedia of New York City. New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press. p. 324.

- ^ Carl Reeve, The Life and Times of Daniel De Leon. New York: Humanities Press, pp. 2-3.

- ^ Stephen Coleman, Daniel De Leon. Manchester, England: University of Manchester Press, 1990; pg. 8.

- ^ Reeve, The Life and Times of Daniel De Leon, pg. 4.

- ^ Seretan, L. Glen Daniel DeLeon: The Odyssey of an American Marxist. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1979; p. 6

- ^ Reeve, The Life and Times of Daniel De Leon, pp. 19-20.

- ^ Lewis Hanke, "The First Lecturer on Hispanic American Diplomatic History in the United States," The Hispanic American Historical Review, Vol. 16, No. 3 (Aug. 1936), pp. 399-402.

- ^ Daniel De Leon, The Conference at Berlin on The West-African Question

- ^ Reeve op cit. pp.4-5

- ^ "Who Was Daniel de Leon?".

- ^ Coleman, op. cit. p.9

- ^ Reeve op cit. pp.6

- ^ Daniel De Leon (1904). "DeLeon Replies". Retrieved February 22, 2007.

- ^ a b Fred W. Thompson and Patrick Murfin, The IWW: Its First Seventy Years, 1905-1975, 1976; pg. 39.

- ^ "Daniel De Leon Passes Away" (PDF). The Alaska Socialist. June 30, 1914.

- ^ Dan Jakopvich, "Revolution and the party in Gramsci’s thought." IV Online magazine (IV406, Nov. 2008), [1], See section: "The dialectics of consent and coercion."

- ISBN 0345331818.

Further reading

- Stephen Coleman, Daniel De Leon, Manchester, England: Manchester University Press.

- W.J. Ghent,"Daniel De Leon" in Dictionary of American Biography. New York: American Council of Learned Societies, 1928-1936.

- Lewis Hanke The first lecturer on Hispanic American diplomatic history. Durham, N.C., 1936 (Reprinted from The Hispanic American historical review, vol. XVI, no. 3, August, 1936)

- Frank Girard and Ben Perry, Socialist Labor Party, 1876-1991: A Short History. Philadelphia: Livra Books, 1991.

- David Herreshoff, "Daniel De Leon: The Rise of Marxist Politics," in Harvey Goldberg ed. American Radicals: Some Problems and Personalities. New York, Monthly Review Press, 1957.

- American Disciples of Marx: From the Age of Jackson to the Progressive Era. Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 1967.

- Olive M. Johnson, Daniel De Leon, American Socialist Pathfinder. New York: New York Labor News Company, 1923.

- Olive M. Johnson and Henry Kuhn, The Socialist Labor Party: During Four Decades, 1890-1930. Part 1. Part 2. New York: New York Labor News Company, 1931.

- Charles A. Madison, "Daniel De Leon: Apostle of Socialism," Antioch Review, vol. 5, no. 3 (Autumn 1945), pp. 402–414. In JSTOR

- Arnold Petersen, Daniel DeLeon: Social Architect. New York: New York Labor News Company, 1942.

- Leonid Raiskii, Daniel De Leon; the struggle against opportunism in the American labor movement, New York: New York Labor News Co., 1932.

- Carl Reeve, The Life and Times of Daniel De Leon. New York:AIMS/Humanities Press, 1972.

- L. Glen Seratan, Daniel DeLeon: The Odyssey of an American Marxist, Cambridge, MA: [Harvard University Press, 1979.

- "Daniel De Leon as American," Wisconsin Magazine of History, vol. 61, no. 3 (Spring 1978), pp. 210–223. In JSTOR.

- Daniel De Leon: The Man and his Work: A Symposium. New York: National Executive Committee, Socialist Labor Party, 1919.

- Golden jubilee of De Leonism, 1890-1940: Commemorating the Fiftieth Anniversary of the Founding of the Socialist labor party. New York: National Executive Committee, Socialist Labor Party, 1940.

- Fifty years of American Marxism, 1891-1941: Commemorating the Fiftieth Anniversary of the Founding of the Weekly People. New York: National Executive Committee, Socialist Labor Party, 1940.

- The Vatican in Politics: Ultramontanism, New York Labor News Company 1962