Daniel R. Lucey

Daniel R. Lucey | |

|---|---|

| Born | Castle Air Force Base, California, US |

| Citizenship | American |

| Education |

|

| Occupation | Infectious diseases professor |

| Known for | Research in infectious diseases |

| Medical career | |

| Profession | Infectious diseases |

| Research | Emerging infectious diseases |

| Awards |

|

Daniel R. Lucey is an American physician, researcher, clinical professor of medicine of

Lucey comes from a military family in California. He graduated in

He spent much of the 1990s studying HIV and vaccines. As chief of infectious diseases at the

In 2003, Lucey was involved in

He has analysed, monitored and responded to several

His awards include the 2001 Walter Reed Medal, and the United States Department of the Army's Commander's Award for Public Service, for the care he gave to those injured at The Pentagon on September 11, 2001.

Early life and education

Daniel R. Lucey was born at Castle Air Force Base, into a military family in Merced County, California and spent his childhood in various parts of the United States including Florida, Ohio, Virginia, South Carolina, Pennsylvania and North Dakota.[1][2]

In 1973, he joined

Early medical career

He gained an

In 1988 he gained a

From 1988 to 1990 he was attending physician at

Washington Hospital Center

In 2001, as chief of infectious diseases at the

Anthrax

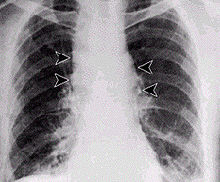

Lucey contributed to the preparedness of the hospital for the subsequent 2001 anthrax attacks by arranging stock piles of antibiotics. Several media companies and two U.S. senators had received letters containing anthrax spores, infecting 22 people in total, five of whom died.[1][8][11][12] Of these cases, 11 involved the skin and 11 were in the lungs (inhalation anthrax).[13] Antibiotics needed to be given quickly.[14] Noting that the first case of anthrax presented with meningitis, Lucey emphasised that should a diagnosis of anthrax meningitis ever be made, a public health response should be triggered.[13]

He has published works on

Smallpox vaccination program

In 2003, Lucey was involved in a campaign to administer smallpox vaccinations to hundreds of thousands of workers.[19] Despite the mounting cost of the campaign and doubts about it being necessary, Lucey in 2003, as director of the Center for Biologic Counterterrorism and Emerging Diseases at the Washington Hospital Center, endorsed the vaccination of healthcare workers and stated that "the threat is definitely real. This is a dangerous time," and advised "for ourselves to be protected, and to then be able to take care of patients and contribute to a large-scale vaccination program."[20]

Lead contamination

In February 2004, a few days after starting work with biodefense at the Washington DC department of health, Lucey was present at a taskforce meeting on the

Georgetown University Medical Center

Since 2004, as adjunct professor of

In 2014, he became a senior scholar with the O’Neill Institute for National and Global Health Law at Georgetown University.

Emerging infectious diseases

Science writer, Laura Stephenson Carter, wrote in the 2012 alumni album of Dartmouth College, that for over 30 years Lucey has been "chasing things you wouldn't want to catch".[1] He coined the term "pan-epidemic",[24] and between 2003 and 2016, he spent time researching infectious disease outbreaks in several countries.[8]

SARS 2003

In 2003 he worked on the SARS outbreaks in Guangzhou China, Hong Kong and Toronto, Canada, where the affected hospitals came to be known as SARS hospitals.[25] At the time, regarding personal protective equipment, Lucey stated that "getting all hospital workers to comply with standard infection control procedures—all the time—was a key to stopping an outbreak of SARS in 2003 ... someone stood there and monitored you to make sure you followed, step by step by step, putting it on properly and taking it off."[26]

Bird flu

Subsequently, he worked on the H5N1 bird flu outbreak in Thailand, Indonesia, Vietnam and Egypt, and the H1N1 flu in Egypt.[1][8][27]

MERS

He worked on

Ebola in Western Africa

He treated people with ebola during the ebola outbreak in Liberia, Guinea and Sierre Leone, where he helped in the isolation unit at Connaught Hospital in Freetown.[8][29][30]

Zika

In 2016, in the

Nipah virus

Lucey visited Bangladesh during its

More than a decade later, when in 2018,

Yellow fever

On the question of whether Asia will ever encounter an outbreak of yellow fever, Lucey showed concern when, in 2016, an outbreak in Angola led to several infected travellers reaching China.[37] He worked on yellow fever during that outbreak, highlighting difficulties should mass quantities of vaccine be required.[38][39][40]

Other emerging infectious diseases

Other involvements have included the chikungunya outbreak in Pakistan, H7N9 influenza in China and the plague in Madagascar.[38]

He was one expert who called for the

COVID-19 pandemic

Reporting on his views of the

Awards

In 1982, while at Dartmouth Medical School, he gained membership to the AOA Medical Honor Society.[3][12] In 1988, he received the young investigator award from the American Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene.[49]

For his work in preparing the city of Washington for the anthrax attacks, Lucey received the Walter Reed Medal in 2001. The following year the United States Department of the Army awarded him the Commander's Award for Public Service, for the care he gave to those injured at The Pentagon on September 11, 2001. In 2003, he received a Distinguished Service Award from the District of Columbia Hospital Association for Bioterrorism Preparedness.[12] In the same year, the Medical Society of the District of Columbia awarded him their Meritorious Service Award.[6]

Selected publications

- "Development and evaluation of a quantitative, touch-down, real-time PCR assay for diagnosing Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia". . Hans Henrik Larsen et al.

- "The emerging zika pandemic: enhancing preparedness". . Co-authored with Lawrence O. Gostin.

- "One health education for future physicians in the pan-epidemic “Age of Humans”". . Co-authored with Sabrina Sholts, Halsie Donaldson, Joseph White, and Stephen R. Mitchell.

- "Enhancing preparation for large nipah outbreaks beyond Bangladesh: Preventing a tragedy like Ebola in West Africa". . Co-authored with Halsie Donaldson.

- "Boosting Global Yellow Fever Vaccine Supply for Epidemic Preparedness: 3 Actions for China and the USA". Virologica Sinica. Vol. 34, Issue 3 (June 2019), pp. 235–239. . Co-authored with K. R. Kent.

- "Coronavirus—unknown source, unrecognized spread, and pandemic potential". Think Global Health. (February 6, 2020). Co-authored with K. R. Kent.

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Carter, Laura Stephenson (2012). "Daniel Lucey, M.D. '81: Outbreak expert" (PDF). Dartmouth Medicine Magazine: 48–49. Retrieved January 29, 2020.

- ^ Szabo, Liz. "Doctor treating Ebola: 'I've been given a gift'". USA TODAY. Retrieved February 3, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Lucey, Daniel R. (2015). Daniel R. Lucey: Curriculum Vitae Archived February 1, 2020, at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Seidman, Lauren (2019). "Dartmouth Medicine Magazine :: Fighting the Viruses of the Future" (PDF). dartmed.dartmouth.edu. pp. 26–27. Retrieved February 17, 2020.

- ^ a b "A Tour with Dr. Daniel Lucey – Outbreak: Epidemics in a Connected World Exhibit at the Smithsonian Museum of Natural History". The Pandora Report. December 13, 2019. Retrieved February 1, 2020.

- ^ a b c "DOH appoints Daniel Lucey Interim CMO, Robert Johnson Director of Substance Abuse, February 17, 2004". www.dcwatch.com. February 17, 2004. Retrieved February 27, 2020.

- ^ "PMAC | Prince Mahidol Award Conference". pmac2018.com. Retrieved February 1, 2020.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-19-060488-2.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-4223-3254-2.

- ^ a b "Daniel R. Lucey". Georgetown Law. Archived from the original on March 9, 2020. Retrieved January 31, 2020.

- ^ Twombly, Renee (February 15, 2014). "A Modern Day Virus Hunter". Georgetown University Medical Center. Retrieved February 3, 2020.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-309-21808-5.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-8261-0250-8.

- ISBN 978-0-12-370466-5.

- PMID 25942409.

- PMID 21991452.

- ^ "Most effective anthrax treatment: rapid diagnosis, antibiotics and lung drainage, va-Stanford study finds". News Center. Retrieved February 4, 2020.

- ^ "Details - Public Health Image Library(PHIL)". phil.cdc.gov. Retrieved March 3, 2020.

- ^ Davenport, Christian. "Smallpox Strategies Shifting". www.ph.ucla.edu. Retrieved February 27, 2020.

- ^ Connolly, Ceci (April 13, 2003). "U.S. Smallpox Vaccine Program Lags". The Washington Post. Retrieved February 27, 2020.

- ^ United States. Congress. Senate. Committee on Environment and Public Works (2004). Water Infrastructure Financing Act: report of the Committee on Environment and Public Works, United States Senate, to accompany S. 2550 together with additional views (including cost estimate of the Congressional Budget Office). U.S. Government Printing Office. p. 66.

- ISBN 9780160883200.)

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link - ^ Reeder, Angela Roberts. "Meet the People Leading the Fight Against Pandemics". www.smithsonianmag.com. Retrieved February 28, 2020.

- ISSN 0028-7504. Retrieved February 27, 2020.

- ^ "A Modern Day Virus Hunter". Georgetown University Medical Center. February 15, 2014. Retrieved February 28, 2020.

- ^ "How U.S. Hospitals Are Planning To Stop The Deadly MERS Virus". Colorado Public Radio. May 14, 2014. Retrieved February 27, 2020.

- ^ Mirgani, Suzi (September 15, 2014). "Daniel Lucey on Global Viral Outbreaks". Center for International and Regional Studies - Georgetown University in Qatar. Retrieved February 18, 2020.

- ^ Fox, Maggie (May 13, 2014). "As MERS Fears Spread, History Offers Sobering Lesson". NBC News. Retrieved February 27, 2020.

- ^ Phillip, Abbey. Rise in new cases shows Ebola has not released its deadly grip. The Washington Post, June 12, 2015

- ^ Neergaard, Lauran (September 11, 2014). "Facing Ebola for first time, doctor learns to use crucial safety gear, then helps teach others". canada.com. Archived from the original on February 28, 2020. Retrieved February 28, 2020.

- ^ Botelho, Greg (January 28, 2016). "Zika virus 'spreading explosively,' WHO leader says". CNN. Retrieved January 31, 2020.

- ^ a b c "Huffington Post India". huffington1855.rssing.com. June 6, 2018. Retrieved February 29, 2020.

- ^ Parry, Nicholas (June 3, 2019). "A resurgence of the Nipah virus?". Health Issues India. Retrieved February 28, 2020.

- ^ "Deadly Nipah virus outbreak hits southern India". www.healio.com. May 22, 2018. Retrieved February 28, 2020.

- ^ "Nipah Outbreak Death Toll Increases To 16; Researchers Warn Of Potential For Virus's Further Spread". The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation. June 6, 2018. Retrieved January 31, 2020.

- PMID 31006350.

- ^ "As the World Is Hit with Vaccine Shortages, Will This Mosquito-Borne Virus Find Its Way to Asia?". ContagionLive. October 13, 2017. Retrieved February 27, 2020.

- ^ a b "Daniel R. Lucey". O'Neill Institute. Archived from the original on March 17, 2020. Retrieved January 30, 2020.

- ^ "What You Should Know About Yellow Fever". Undark Magazine. May 27, 2016. Retrieved January 31, 2020.

- ^ "Yellow fever - Africa (92): WHO, Angola, Congo DR, letter to WHO". www.promedmail.org. International Society for Infectious Diseases. Retrieved February 1, 2020.

- ^ Klain, Ronald A.; Lucey, Daniel (July 10, 2019). "Opinion | It's time to declare a public health emergency on Ebola". Washington Post. Retrieved July 20, 2019.

- ^ "New Images of Novel Coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 Now Available | NIH: National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases". www.niaid.nih.gov. February 13, 2020. Retrieved February 26, 2020.

- ^ Otto, M. Alexander (January 27, 2020). "Wuhan Virus: What Clinicians Need to Know". Medscape. Retrieved January 30, 2020.

- ^ Cohen, Jon (January 26, 2020). "Wuhan seafood market may not be source of novel virus spreading globally". Science | AAAS. Archived from the original on January 27, 2020. Retrieved February 1, 2020.

- S2CID 210982800.

- PMID 32072569.

- ^ Barton, Antigone (January 25, 2020). "UPDATE Wuhan coronavirus – 2019-nCoV Q&A #6: An evidence-based hypothesis". Science Speaks: Global ID News. Retrieved February 1, 2020.

- ^ "COVID-19: What You Need to Know". www.idsociety.org. Retrieved February 25, 2020.

- ^ Membership Directory: Awards. American Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, p 131.

External links

- S&ED Preview & Korea's MERS Response. Lucey's response to MERS (interview)

- Daniel Lucey - Lessons from Traveling to Zika, Ebola, MERS, FLU, and SARS Pandemics. YouTube video 2015

- This Earth Day, the Planet’s Health is Your Health. Smithsonian Institution (2017)

- Defending Against Aerosol Anthrax Attacks on US Cities

- “Much more must be done to implement post-Ebola reforms”. The British Medical Journal Opinion. January 23, 2017

- Anthrax: Diagnosis, Clinical Staging, and Risk Communication. Presentation February 16, 2017