David Colquhoun

David Colquhoun | |

|---|---|

David Colquhoun in 2013 | |

| Born | 19 July 1936[2] Birkenhead, Cheshire, England |

| Alma mater |

|

| Known for |

|

| Awards | Humboldt Prize (1990) |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields |

|

| Institutions | |

| Thesis | The characterisation and adsorption of sensitising antibodies (1965) |

| Doctoral advisor | W.L.M. Perry W.E. Brocklehurst[citation needed] |

| Website | dcscience |

David Colquhoun

Early life and education

Colquhoun was born on 19 July 1936 in Birkenhead, UK.

Upon completion of his PhD, Colquhoun conducted further research (largely unsuccessful) on immunological problems at UCL from 1964 to 1969. During this time he published a book on statistics.

Scientific career

Colquhoun researched the nature of the molecular interactions that cause single ion channels to open and shut, and what it is that controls the speed of

Work with single ion channels

In 1977 Colquhoun and Hawkes[12] predicted that ion channel openings would be expected to occur in brief bursts rather than as single openings, and this prediction was verified in experiments with Bert Sakmann, in Göttingen and London (1981).[13][14] This work led to the first solution of the classical pharmacological problem of measuring separately the affinity and efficacy of an agonist.[15] In the context of ion channels, this problem is also known as the binding/gating problem. This problem remains unsolved for G protein-coupled receptors, because it was shown in 1987 that the classical methods for determining affinity and efficacy were based on a misapprehension.[16]

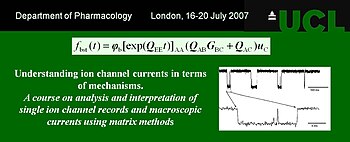

The 1985 paper was later nominated as a "classic"[17] by The Journal of Physiology.[18] In 1982 Colquhoun & Hawkes published a paper[19] on the theory of bursts (and clusters of bursts) which gave a general expression for the distribution of the burst length (shown here on the design for a mug for those who attend a course designed to teach the mathematics needed for the equation).[20]

It was clear that the burst length was what controlled the decay rate of synaptic currents, though the formal relationship was not derived until 1998.[21]

Missed short events

Although the general theory of single channel behaviour was completed in 1982, it could not be used in practice for fitting mechanisms to data, because the recording apparatus is incapable of detecting events shorter than, at best, about 20 microseconds. The effect of missing short shuttings is to make openings appear to be longer than they really are (and likewise for shuttings). To use the method of maximum likelihood it was essential to derive the distribution of the length of what is actually seen, apparent open times and apparent shut times. Although the

Intermediate shut states

All the early work was based on mechanisms that were essentially generalisations of the simple scheme proposed by del Castillo & Katz in 1957,[26] in which the receptor existed in only two conformations, open and shut. It was only when the glycine receptor was investigated that it was realised that it was possible to detect an intermediate shut state (dubbed the "flipped" conformation), between the resting conformation and the open state.[27] Subsequently, it was discovered that this extra "flipped" conformation was detectable too in the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor. Lape et al. (2008)[28] found that partial agonists were partial, not, as had been supposed since 1957, because of a deficiency in the open reaction itself, but because of a deficiency at an earlier stage, a reluctance to move from the resting conformation to the intermediate shut state that precedes opening. The actual shut-open conformation change turned out to be much the same for partial agonists as it was for full agonists. In the original formulation the flipping reaction was supposed to be a concerted transition. The essentials of this new mechanism were confirmed by Mukhtasimova et al. (2009),[29] who generalised it to the case where the subunits can flip independently.

Statistical inference

After retiring from single ion channel work, Colquhoun maintained an interest in statistical inference. His 2014 paper, An investigation of the false discovery rate and the misinterpretation of p-values,[30] contributed to the p-value debate, and to the discussion of reproducibility in science. This paper has been followed by others which have explored the basis of inductive inference,[31] and which have investigated in more depth the alternatives to using p values.[32][4] The hazards of reliance on p-values was emphasised in[32] by pointing out that even observation of p = 0.001 was not necessarily strong evidence against the null hypothesis. Despite the fact that the likelihood ratio in favour of the alternative hypothesis over the null is close to 100, if the hypothesis was implausible, with a prior probability of a real effect being 0.1, even the observation of p = 0.001 would have a false positive risk of 8 percent. It would not even reach the 5 percent level. It was recommended that the terms "significant" and "non-significant" should not be used. P values and confidence intervals should still be specified, but they should be accompanied by and indication of the false positive risk. It was suggested that the best way to do this is to calculate the prior probability that would it would be necessary to believe in order to achieve a false positive risk of, say, 5%. Or, perhaps more simply, the p value could be supplemented by the minimum false positive risk, FPR50, -that calculated for a prior probability of 0.5.[4] Although this would be safe only for plausible hypotheses, it would be a great improvement on giving on p values and confidence intervals. The calculations can be done with R scripts that are provided,[32][4] or, more simply, with a web calculator.[33]

Criticism of scientific fraud, alternative medicine and managerialism

Colquhoun has been an outspoken

DC's Improbable Science website

Colquhoun created his personal website, DC's Improbable Science,

Controversy over website hosting

In May 2007, Colquhoun announced on his website that recent comments he had made questioning the validity of claims made by Ann Walker, a lecturer in Nutrition at the

Alternative medicine and the government

Colquhoun was a member of the Conduct and Competence Committee of the Complementary and Natural Healthcare Council (CNHC), a regulatory body for alternative medicine in the UK. Colquhoun has stated he was surprised at being accepted for the position. However, he was dismissed in August 2010.[47]

Colquhoun continues to write on the danger of the alternative medicine industry using government regulation for its own ends. In a 2012 article from the Scottish Universities Medical Journal, he wrote:[48]

There are various levels of regulation. The "highest" level is the statutory regulation of osteopathy and chiropractic. The General Chiropractic Council (GCC) has exactly the same legal status as the General Medical Council (GMC). This ludicrous state of affairs arose because nobody in John Major's government had enough scientific knowledge to realise that chiropractic, and some parts of osteopathy, are pure quackery. The problem is that organisations like the GCC function more to promote their discipline rather than regulate them.

Awards and honours

Colquhoun was elected a

Personal life

In 1976, he married Margaret Ann Boultwood. They have a son and two granddaughters.

Outside academia, Colquhoun has enjoyed (in chronological order) boxing, sailing (21 ft, and later 31 ft sloops), flying light aircraft, long-distance running (10 km, half-marathon and marathon), and mountain walking.[49] In 1988 he did the London marathon in 3 hours 57 minutes. For his 65th birthday, in 2001, he walked across the Alps (Oberstdorf, Germany, to Merano, Italy).[50]

References

- ^ a b David Colquhoun publications indexed by Google Scholar

- ^ doi:10.1093/ww/9780199540884.013.U11583. (Subscription or UK public library membershiprequired.)

- ^ a b c "David Colquhoun's Improbable Science: Truth, falsehood and evidence, investigations of dubious and dishonest science". Archived from the original on 2 March 2013.

- ^ S2CID 85530643.

- ^ "UCL Pharmacology: Prof. David Colquhoun". University College London. 14 February 2019.

- ^ a b "Professor David Colquhoun FRS". London: Royal Society. Archived from the original on 17 November 2015.

- ^ a b

"An Uncommon Scientist with a lot of Common Sense" (PDF). University College London.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Colquhoun, David (1964). "The characterization and adsorption of sensitizing antibodies".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ISBN 978-0-19-854119-6.

- ^

"Scholars: David Colquhoun" (PDF). University College London.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ PMID 12562901.

- S2CID 6060354.

- S2CID 4353962.

- PMID 2419552.

- PMID 9846630.

- ^ Colquhoun D (1987). Affinity, efficacy and receptor classification: is the classical theory still useful? In Perspectives on hormone receptor classification, eds. Black JW, Jenkinson DH, & Gerskowitch VP, pp. 103–114. Alan R. Liss Inc., New York.

- ^ Classical Perspectives, "Classical Perspectives are commentaries on 'classic' articles in The Journal that have stimulated new lines of research and continue to be highly cited. The articles are commissioned from acknowledged experts in the area covered by the article and should indicate how the article has contributed to current developments in the field." The Journal of Physiology

- PMID 17363381.

- PMID 6131450.

- ^ UCL's workshop Analysis and interpretation of single ion channel records and macroscopic currents using matrix methods.

- PMID 9625862.

- S2CID 122883551.

- PMID 1279733.

- S2CID 118010415.

- ^ Sivilotti, Lucia (10 March 2011). "Programs description". OneMol.org.uk.

- S2CID 6302752.

- PMID 15574743.

- PMID 18633353.

- PMID 19339970.

- PMID 26064558.

- ^ Colquhoun, David. "The problem with p-values". Aeon Magazine. Retrieved 11 December 2016.

- ^ PMID 29308247.

- ^ Longstaff, Colin; Colquhoun, David. "Calculator for false positive risk (FPR)". UCL.

- ^ S2CID 29071826.

- PMID 19279607.

- PMID 12774093.

- ^ Colquhoun, David (15 August 2007). "The age of endarkenment". The Guardian.

- ^ "Rise in applications for 'soft' subjects panned as traditional courses lose out". 27 July 2007.

- ^ Colquhoun, David (2007). "How to get good science". Physiology News. 69: 12–14.

- ^ Information Tribunal appeal judgement

- ^ Colquhoun's response to judgement

- ^ Appleyard, Bryan (22 February 2009). "A guide to the 100 best blogs: part II". The Sunday Times. Archived from the original on 28 May 2015. Retrieved 5 February 2013.

- ^ UK Science Blog. Good Thinking Society.

- ^ Colquhoun, David (1 December 2014). "Publish and perish at Imperial College London: the death of Stefan Grimm". DCscience.net. Retrieved 25 September 2015.

- ^ "Freedom of speech and litigious herbalists".

- ^

"Joint Statement by Professor Colquhoun and UCL". University College London. 12 June 2007.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "Why the Complementary and Natural Healthcare Council (CNHC) can't succeed (in which DC gets fired)". 11 August 2010.

- ^ Colquhoun, David (2012). "Regulation of Alternative Medicine- why it doesn't work" (PDF). Scottish Universities Medical Journal.

- ^ "DC's sports". David Colquhoun. Retrieved 3 December 2019.

- ^ "Walk across the Alps, 2001". David Colquhoun. Retrieved 2 June 2019.