De architectura

De architectura (On architecture, published as Ten Books on Architecture) is a treatise on

It contains a variety of information on Greek and Roman buildings, as well as prescriptions for the planning and design of military camps, cities, and structures both large (aqueducts, buildings, baths, harbours) and small (machines, measuring devices, instruments).

From references to them in the text, we know that there were at least a few illustrations in original copies (perhaps eight), but none of these survived in medieval manuscript copies. This deficiency was remedied in 16th-century printed editions, which became illustrated with many large plates.

Origin and contents

Probably written between 30–20 BC,

Though often cited for his famous "triad" of characteristics associated with architecture – utilitas, firmitas and venustas (utility, strength and beauty) – the aesthetic principles that influenced later treatise writers were outlined in Book III. Derived partially from Latin rhetoric (through Cicero and Varro), Vitruvian terms for order, arrangement, proportion, and fitness for intended purposes have guided architects for centuries, and continue to do so.

The Roman author gives advice on the qualifications of an architect (Book I) and on types of architectural drawing.[5]

The ten books or scrolls are organized as follows:

De architectura – Ten Books on Architecture

- Roman technology, hoisting, pneumatics

Roman architects were skilled in engineering, art, and craftsmanship combined. Vitruvius was very much of this type, a fact reflected in De architectura. He covered a wide variety of subjects he saw as touching on architecture. This included many aspects that may seem irrelevant to modern eyes, ranging from mathematics to astronomy, meteorology, and medicine. In the Roman conception, architecture needed to take into account everything touching on the physical and intellectual life of man and his surroundings.

Vitruvius, thus, deals with many theoretical issues concerning architecture. For instance, in Book II of De architectura, he advises architects working with bricks to familiarise themselves with pre-Socratic theories of matter so as to understand how their materials will behave. Book IX relates the abstract

Buildings

Vitruvius sought to address the ethos of architecture, declaring that quality depends on the social relevance of the artist's work, not on the form or workmanship of the work itself. Perhaps the most famous declaration from De architectura is one still quoted by architects: "Well building hath three conditions: firmness, commodity, and delight". This quote is taken from Sir Henry Wotton's version of 1624, and accurately translates the passage in the work, (I.iii.2) but English has changed since then, especially in regard to the word "commodity", and the tag may be misunderstood. In modern English it would read: "The ideal building has three elements; it is sturdy, useful, and beautiful."

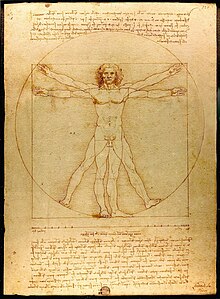

Vitruvius also studied human proportions (Book III) and this part of his canones were later adopted and adapted in the famous drawing Homo Vitruvianus ("Vitruvian Man") by Leonardo da Vinci.

Domestic architecture

While Vitruvius is fulsome in his descriptions of religious buildings, infrastructure and machinery, he gives a mixed message on domestic architecture. Similar to Aristotle, Vitruvius offers admiration for householders who built their own homes without the involvement of an architect.[6][7] His ambivalence on domestic architecture is most clearly read in the opening paragraph of the Introduction to Book 6.[8] Book 6 focusses exclusively on residential architecture but as architectural theorist Simon Weir has explained, instead of writing the introduction on the virtues of residences or the family or some theme related directly to domestic life; Vitruvius writes an anecdote about the Greek ethical principle of xenia: showing kindness to strangers.[9]

Roman technology

De architectura is important for its descriptions of many different machines used for engineering structures, such as hoists,

Aqueducts and mills

Books VIII, IX, and X of De architectura form the basis of much of what is known about Roman technology, now augmented by archaeological studies of extant remains, such as the

His book would have been of assistance to

Materials

Vitruvius described many different construction materials used for a wide variety of different structures, as well as such details as stucco painting. Cement, concrete, and lime received in-depth descriptions, the longevity of many Roman structures being mute testimony to their skill in building materials and design.

He advised that

Vitruvius related the famous story about Archimedes and his detection of adulterated gold in a royal crown. When Archimedes realized the volume of the crown could be measured exactly by the displacement created in a bath of water, he ran into the street with the cry of "Eureka!", and the discovery enabled him to compare the density of the crown with pure gold. He showed the crown had been alloyed with silver, and the king was defrauded.

Dewatering machines

Vitruvius described the construction of the

Force pump

Vitruvius also mentioned the several automatons Ctesibius invented, and intended for amusement and pleasure rather than serving a useful function.

Central heating

Vitruvius outlined the many innovations made in building design to improve the living conditions of the inhabitants. Foremost among them is the development of the

Surveying instruments

That Vitruvius must have been well practised in surveying is shown by his descriptions of surveying instruments, especially the water level or

Sea level change

In Book IV Chapter 1 Subsection 4 of De architectura is a description of 13

Survival and rediscovery

Manuscripts

Vitruvius's work is one of many examples of Latin texts that owe their survival to the palace scriptorium of Charlemagne in the early 9th century. (This activity of finding and recopying classical manuscripts is part of what is called the Carolingian Renaissance.) Many of Vitruvius's surviving works derive from an extant manuscript rewritten there, British Library manuscript Harley 2767.[12]

These texts were not just copied, but also known at the court of Charlemagne, since his historian, bishop

Many copies of De architectura, dating from the 8th to the 15th centuries, did exist in manuscript form during the Middle Ages and 92 are still available in public collections, but they appear to have received little attention, possibly due to the obsolescence of many specialized Latin terms used by Vitruvius [citation needed] and the loss of most of the original 10 illustrations thought by some to be helpful in understanding parts of the text.

Vitruvius's work was "rediscovered" in 1416 by the Florentine humanist Poggio Bracciolini, who found it in the Abbey library of Saint Gall, Switzerland. He publicized the manuscript to a receptive audience of Renaissance thinkers, just as interest in the classical cultural and scientific heritage was reviving.

Printed editions

The first printed edition (editio princeps), an

Translations into Italian were in circulation by the 1520s, the first in print being the translation with new illustrations by

John Shute had drawn on the text as early as 1563 for his book The First and Chief Grounds of Architecture. Sir Henry Wotton's 1624 work The Elements of Architecture amounts to a heavily-influenced adaptation, while a 1692 translation was much abridged. English-speakers had to wait until 1771 for a full translation of the first five volumes and 1791 for the whole thing. Thanks to the art of printing, Vitruvius's work had become a popular subject of hermeneutics, with highly detailed and interpretive illustrations, and became widely dispersed.

Of the many later editions, the 1914 Ten Books on Architecture translated by Morris H. Morgan, Ph.D, LL.D. Late Professor of Classical Philology in Harvard University, is fully available at Project Gutenberg, and from the Internet Archive.[14]

Impact

The rediscovery of Vitruvius's work had a profound influence on architects of the

The English architect

Astrolabe

The earliest evidence of use of the stereographic projection in a machine is in De architectura, which describes an anaphoric clock (it is presumed, a clepsydra or water clock) in Alexandria. The clock had a rotating field of stars behind a wire frame indicating the hours of the day. The wire framework (the spider) and the star locations were constructed using the stereographic projection. Similar constructions dated from the 1st to 3rd centuries have been found in Salzburg and northeastern France, so such mechanisms were, it is presumed,[by whom?] fairly widespread among Romans.[citation needed]

See also

- De re aedificatoria – Classic architectural treatise by Leon Battista Alberti

- I quattro libri dell'architettura – 1570 treatise on architecture by Andrea Palladio

- Pliny the Elder – 1st-century Roman military commander and writer

- Ancient Roman architecture – Ancient architectural style

- Ancient Roman engineering – Engineering accomplishments of the ancient Roman civilization

- Ancient Roman technology – Technological accomplishments of the ancient Roman civilization

References

- ^ Kruft, Hanno-Walter. A History of Architectural Theory from Vitruvius to the Present (New York, Princeton Architectural Press: 1994).

- ^ Vitruvius. Ten Books on Architecture, Ed. Ingrid Rowland with illustrations by Thomas Noble Howe (Cambridge, Cambridge University Press: 1999)

- ^ See William L. MacDonald, The Architecture of the Roman Empire: An Introductory Study (New Haven, Yale University Press: 1982): 10-11.

- ^ Cartwright, Mark (2015-04-22). "Vitruvius". World History Encyclopedia. Retrieved 2 June 2022.

- ^ Vitruvius: On Architecture, Book I, edited and translated into English by Frank Granger (Cambridge, Harvard University Press: 1931-34).

- ^ "Page:Vitruvius the Ten Books on Architecture.djvu/205 - Wikisource, the free online library". en.wikisource.org. Retrieved 2020-04-28.

- ^ "Aristotle, Economics, Book 1, section 1345a". www.perseus.tufts.edu. Retrieved 2020-04-28.

- ^ "Page:Vitruvius the Ten Books on Architecture.djvu/203 - Wikisource, the free online library". en.wikisource.org. Retrieved 2020-04-28.

- S2CID 145783068.

- ^ Gilman, Paul. ""Securing a Future for Essex's Past" Heritage Conservation Planning Division, Essex County Council England". Esri.com. Retrieved 2008-10-29.

- JSTOR 530219.

- ^ "Details of an item from the British Library Catalogue of Illuminated Manuscripts". Bl.uk. 2003-11-30. Archived from the original on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2012-11-16.

- S2CID 195019013.

- ^ Vitruvius, Pollio (1914). The Ten Books on Architecture. Translated by Morgan, Morris Hicky. Illustrations prepared by Herbert Langford Warren. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Further reading

- B. Baldwin: The Date, Identity, and Career of Vitruvius. In: Latomus 49 (1990), 425-34

- I. Rowland, T.N. Howe: Vitruvius. Ten Books on Architecture. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 1999, ISBN 0-521-00292-3

External links

- The Ten Books of Architecture online: cross-linked Latin text and English translation

- Original Latin text, version 2

- Ten Books on Architecture at Project Gutenberg (Morris Hicky Morgan translation with illustrations)

Ten Books on Architecture public domain audiobook at LibriVox

Ten Books on Architecture public domain audiobook at LibriVox- Reprint by Dover Publications

- Modern bibliography on line (15th-17th centuries) (in French)

- Vitruvii, M. De architectura. Naples, c. 1480. At Somni.