Deep South

Deep South | |

|---|---|

| Nickname: The Cotton States | |

States highlighted are geographically the southernmost states in the contiguous United States. The states in dark red comprise what is commonly referred to as the Deep South subregion, while the Deep South overlaps into portions of those in lighter red. | |

| Country | United States |

The Deep South or the Lower South is a cultural and geographic subregion of the Southern United States. The term was first used to describe the states which were most economically dependent on plantations and slavery. After the American Civil War ended in 1865, the region suffered economic hardship and was a major site of racial tension during and after the Reconstruction era. Before 1945, the Deep South was often referred to as the "Cotton States" since cotton was the primary cash crop for economic production.[1][2] The civil rights movement in the 1950s and 1960s helped usher in a new era, sometimes referred to as the New South. The Deep South is part of the highly-religious, socially conservative Bible Belt and is currently a Republican Party stronghold.

Usage

The term "Deep South" is defined in a variety of ways: Most definitions include the following states: Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama, Georgia, and South Carolina.[3] Texas and Florida are sometimes included,[4] due to being peripheral states, having coastlines with the Gulf of Mexico, their history of slavery, large African American populations, and being part of the historical Confederate States of America.

The

The seven states that seceded from the United States before the firing on Fort Sumter and the start of the American Civil War, which originally formed the Confederate States of America. In order of secession, they are South Carolina, Mississippi, Florida, Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, and Texas.

The first six states to secede were those that held the largest percentage of slaves. Ultimately, the Confederacy included eleven states. A large part of the original

Origins

Although often used in history books to refer to the seven states that originally formed the Confederacy, the term "Deep South" did not come into general usage until long after the Civil War ended. For at least the remainder of the 19th century, "Lower South" was the primary designation for those states. When "Deep South" first began to gain mainstream currency in print in the middle of the 20th century, it applied to the states and areas of South Carolina, Georgia, southern Alabama, northern Florida, Mississippi, northern Louisiana, West Tennessee, southern Arkansas, and eastern Texas, all historical areas of cotton plantations and slavery.[10] This was the part of the South many considered the "most Southern."[11]

Later, the general definition expanded to include all of South Carolina, Georgia, Alabama, Mississippi, and Louisiana, as well as often taking in bordering areas of West Tennessee, East Texas and North Florida. In its broadest application, the Deep South is considered to be "an area roughly coextensive with the old cotton belt, from eastern North Carolina through South Carolina, west into East Texas, with extensions north and south along the Mississippi."[9]

Early economics

After the Civil War, the region was economically poor. After

From Reconstruction through the Civil Rights Movement

After 1950, the region became a major center of the

Major cities and urban areas

The Deep South has three major Metropolitan statistical areas (MSAs) located solely within its boundaries, with populations exceeding 1,000,000 residents (Four including Memphis). Atlanta, the 8th largest metro area in the United States, is the Deep South's largest population center, followed by Memphis, New Orleans, and Birmingham.

Metropolitan areas

The 18 Deep South metropolitan areas (MSAs) within the 150 largest population centers in the United States are ranked below:

* Indicates state capital

Other substantial cities include:

| State | Cities |

|---|---|

| Alabama | Montgomery, Tuscaloosa, Auburn, and Dothan |

| Georgia | Columbus, Macon, Valdosta and Athens |

| Louisiana | Alexandria, Monroe, and Lake Charles |

| Mississippi | Meridian, Tupelo, and Hattiesburg |

| South Carolina | Sumter, and Florence |

Climate

As part of the

People

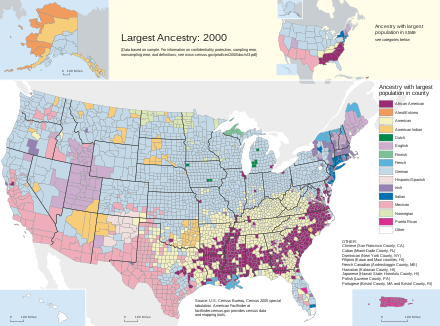

Most White people in the Deep South who identified themselves with one European ethnic group in the 1980 census self-identified as English. This occurred in every southern state with the exception of Louisiana where more White people self-identified as French than English. [16][17] A large number of the White population also derives from ethnic groups of Ireland (Irish and Ulster Scots). With regard to White people in the Deep South who reported only a single European-American ancestry group, the 1980 census showed the following self-identification in each state in this region:

- Alabama – 857,864 of 2,165,653 respondents (41%) self-identified as English only, which was the state's largest ancestral group by a wide margin.

- Georgia – 1,132,184 of 3,009,486 respondents (37.62%) self-identified as English only.

- Mississippi – 496,481 of 1,551,364 respondents (32%) self-identified as English only, which was the state's largest ancestral group by a wide margin.

- Florida – 1,132,033 of 5,159,967 respondents (21.94%) self-identified as English only.

- Louisiana – 480,711 of 2,319,259 respondents (20.73%) self-identified as French only, followed closely by 440,558 English-only respondents (19%).

- South Carolina – 578,338 of 1,706,966 respondents (33.88%) self-identified as English only. This is likely due to the fact that British colonization along the coasts of present-day South Carolina began earlier than colonization of other areas commonly classified as the Deep South.

- Texas – 1,639,322 of 7,859,393 respondents (20.86%) self-identified as English only, which was the state's largest ancestral group by a large margin.

These figures do not take into account people who self-identified as English and some other ancestral group. When the two were added together, people who self-identified as being English with other ancestry, made up an even larger portion of southerners.[18]

As of 2003[update], the majority of Black Americans in the South live in the Black Belt in the American South from Virginia to Texas.[19][20]

Hispanic and Latino Americans largely started arriving in the Deep South during the 1990s, and their numbers have grown rapidly. Politically they have not been very active.[21]

Politics

Political expert Kevin Phillips states that, "From the end of Reconstruction until 1948, the Deep South Black Belts, where only whites could vote, were the nation's leading Democratic Party bastions."[22]

From the late 1870s to the mid-1960s, conservative whites of the Deep South held control of state governments and overwhelmingly identified with and supported the

At the turn of the 20th century, all Southern states, starting with Mississippi in 1890, passed new constitutions and other laws that effectively

Major demographic changes would ensue in the 20th century. During the two waves of the

White southern voters consistently voted for the Democratic Party for many years to hold onto Jim Crow Laws. Once Franklin D. Roosevelt came to power in 1932, the limited southern electorate found itself supporting Democratic candidates who frequently did not share its views. Journalist Matthew Yglesias argues:

The weird thing about Jim Crow politics is that white southerners with conservative views on taxes, moral values, and national security would vote for Democratic presidential candidates who didn't share their views. They did that as part of a strategy for maintaining white supremacy in the South.[30]

Kevin Phillips states that, "Beginning in 1948, however, the white voters of the Black Belts shifted partisan gears and sought to lead the Deep South out of the Democratic Party. Upcountry, pineywoods and bayou voters felt less hostility towards the New Deal and Fair Deal economic and caste policies which agitated the Black Belts, and for another decade, they kept The Deep South in the Democratic presidential column.[22]

Phillips emphasizes the three-way 1968 presidential election:

Wallace won very high support from Black Belt whites and no support at all from Black Belt Negroes. In the Black Belt counties of the Deep South, racial polarization was practically complete. Negroes voted for Hubert Humphrey, whites for George Wallace. GOP nominee Nixon garnered very little backing and counties where Barry Goldwater had captured 90 percent to 100 percent of the vote in 1964.[31]

The Republican Party in the South had been crippled by the disenfranchisement of blacks, and the national party was unable to relieve their past with the South where Reconstruction was negatively viewed. During the

Late 20th century to present

Historian

In 1995, Georgia Republican Newt Gingrich was elected by representatives of a Republican-dominated House as Speaker of the House.

Since the 1990s the white majority has continued to shift toward Republican candidates at the state and local levels. This trend culminated in 2014 when the Republicans swept every statewide office in the Deep South region

Presidential elections in which the Deep South diverged noticeably from the

In the 2020 presidential election, the state of Georgia was considered a toss-up state hinting at a possible Democratic shift in the area. It ultimately voted Democratic, in favor of Joe Biden. During the 2021 January Senate runoff elections, Georgia also voted for two Democrats, Jon Ossoff and Raphael Warnock. However, Georgia still maintains a Republican lean with a PVI rating of R+3 in line with its Deep South neighbors, with Republicans currently controlling every statewide office, its state Supreme Court, and its legislature.

States

From

The demographics of these states changed markedly from the 1890s through the 1950s, as two waves of the Great Migration led more than 6,500,000 African-Americans to abandon the economically depressed, segregated Deep South in search of better employment opportunities and living conditions, first in Northern and Midwestern industrial cities, and later west to California. One-fifth of Florida's black population had left the state by 1940, for instance.[49] During the last thirty years of the twentieth century into the twenty-first century, scholars have documented a reverse New Great Migration of black people back to southern states, but typically to destinations in the New South, which have the best jobs and developing economies.[50]

The District of Columbia, one of the magnets for black people during the Great Migration, was long the sole majority-minority federal jurisdiction in the continental U.S. The black proportion has declined since the 1990s due to gentrification and expanding opportunities, with many black people moving to southern states such as Texas, Georgia, Florida, and Maryland and others migrating to jobs in states of the New South in a reverse of the Great Migration.[50]

Transportation

- U.S. Route 90 runs from Van Horn, Texas to Jacksonville, Florida.

- U.S. Route 11 runs through the Deep South to the Canadian border in New York.

- Interstate 10 is a major transcontinental east–west highway that travels through the far southern portion of the Deep South, with its eastern terminus at I-95 in Jacksonville, Florida.

- Interstate 55 is a major north–south route traveling from Chicago, Illinois to New Orleans, Louisiana. The interstate travels through the Deep South cities of Memphis, Jackson, and New Orleans.

- Interstate 40 is a major transcontinental east–west route that travels from Barstow, California to Wilmington, North Carolina. It meets Interstate 55 in Memphis.

- Interstate 49 is a partially complete interstate running north–south centrally in the United States. It runs currently in the Deep South from Texarkana, Arkansas through Shreveport, and Alexandria to Lafayette, Louisiana.

- Tyler, Shreveport, Jackson, Birmingham, Atlanta, Augusta, and Columbia.

References

- ^ Fryer, Darcy. "The Origins of the Lower South". Lehigh University. Retrieved December 30, 2008.

- ISBN 978-0-19-508808-3. Retrieved December 30, 2008.

- ^ a b "Deep South". The Free Dictionary. Retrieved May 25, 2018.

- ^ a b Neal R. Pierce, The Deep South States of America: People, Politics, and Power in the Seven States of the Deep South (1974), pp 123–61

- ^ Randal Rust. "Cotton". Tennessee Encyclopedia. Retrieved March 22, 2022.

- ^ "History and Culture of the Mississippi Delta Region - Lower Mississippi Delta Region (U.S. National Park Service)". www.nps.gov. Retrieved March 22, 2022.

- ISBN 978-1-61075-032-5.

- ISBN 0-8032-0489-2.

- ^ a b John Reed and Dale Volberg Reed, 1001 Things Everyone Should Know About the South, Doubleday, 1996

- ^ Roller, David C., and Twyman, Robert W., editors (1979). The Encyclopedia of Southern History. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press.

- The Most Southern Place on Earth: The Mississippi Delta and the Roots of Regional Identity(1992) p. vii.

- ^ Ted Ownby, "The Defeated Generation at Work: White Farmers in the Deep South, 1865–1890". Southern Studies 23 (1984): 325–347.

- ^ Edward L. Ayers, The promise of the new South: Life after reconstruction (Oxford University Press, 2007) 187–214, 283–289.

- ^ Clarence Lang, "Locating the civil rights movement: An essay on the Deep South, Midwest, and border South in Black Freedom Studies." Journal of Social History 47.2 (2013): 371–400. Online.

- ^ Howell Raines, My soul is rested: Movement days in the deep south remembered (Penguin, 1983).

- ^ Grady McWhiney, Cracker Culture: Celtic Ways in the Old South (1989)

- ^ David Hackett Fischer, Albion's Seed: Four British Folkways in America (1989) pp 605–757.

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on October 26, 2019. Retrieved October 26, 2015.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - JSTOR 10.7758/9781610440356.

- ^ Wilson, Charles Reagan (October 10, 2017). "Black Belt/Prairie". Mississippi Encyclopedia. Retrieved August 23, 2020.

The Mississippi Black Belt is part of a larger region, stretching from Virginia south to the Carolinas and west through the Deep South, defined by a majority African American population and a long history of cotton production.

- ^ Charles S. Bullock, and M. V. Hood, "A Mile‐Wide Gap: The Evolution of Hispanic Political Emergence in the Deep South." Social Science Quarterly 87.5 (2006): 1117–1135. Online[dead link]

- ^ a b Kevin Phillips, The Emerging Republican Majority: Updated Edition (2nd ed. 2917) p. 232.

- ^ Michael Perman, Pursuit of unity: a political history of the American South (U of North Carolina Press, 2010).

- ^ 6 J. Morgan Kousser, The Shaping of Southern Politics: Suffrage Restriction and the Rise of the One-Party South, 1880–1910 (Yale UP, 1974).

- ^ Michael Perman, Struggle for mastery: Disfranchisement in the South, 1888–1908 (U of North Carolina Press, 2003).

- ^ Gabriel J. Chin & Randy Wagner, "The Tyranny of the Minority: Jim Crow and the Counter-Majoritarian Difficulty, "43 Harvard Civil Rights-Civil Liberties Law Review 65 (2008)[permanent dead link]

- ISBN 9780226845272– via Google Books.

- ^ Earl Black and Merle Black, The rise of southern Republicans (Harvard University Press, 2009).

- ^ Seth C. McKee, The Past, Present, and Future of Southern Politics (2012) online. Google.com

- ^ See Matthew Yglesias, "Why did the South turn Republican?", The Atlantic August 24, 2007.

- ^ Phillips, p. 255

- ^ Harvard Sitkoff, "Harry Truman and the Election of 1948: The Coming of Age of Civil Rights in American Politics." Journal of Southern History 37.4 (1971): 597–616

- ^ Mark Stern, Calculating visions: Kennedy, Johnson, and civil rights (Rutgers UP, 1992).

- ^ Brad Lockerbie, "Race and religion: Voting behavior and political attitudes." Social Science Quarterly 94.4 (2013): 1145–1158.

- ^ Tami Luhby and Jennifer Agiesta, "Exit polls: Clinton fails to energize African-Americans, Latinos and the young" CNN Nov, 9, 2016

- ^ Thomas J. Sugrue, "It's Not Dixie's Fault", The Washington Post, July 17, 2015

- ^ "Demise of the Southern Democrat is Now Nearly Complete". The Sydney Morning Herald. December 12, 2007. Retrieved December 13, 2007.

- ^ Charles S. Bullock III and Mark J. Rozell, eds. The New Politics of the Old South: An Introduction to Southern Politics (2009) p 208.

- ^ "Table 33. Louisiana – Race and Hispanic Origin: 1810 to 1990" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on March 27, 2010.

- ^ "Race and Hispanic Origin for States" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on February 7, 2014. Retrieved June 24, 2013.

- ^ "Table 39. Mississippi – Race and Hispanic Origin: 1800 to 1990" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on March 27, 2010.

- ^ "Table 25. Georgia – Race and Hispanic Origin: 1790 to 1990" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on October 23, 2013. Retrieved June 24, 2013.

- ^ "Table 15. Alabama – Race and Hispanic Origin: 1800 to 1990" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on October 23, 2013. Retrieved June 24, 2013.

- ^ "Table 24. Florida – Race and Hispanic Origin: 1830 to 1990" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on March 27, 2010.

- ^ "Race and Hispanic Origin for States" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on January 20, 2013. Retrieved June 24, 2013.

- ^ "Race and Hispanic Origin for States" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on January 20, 2013. Retrieved June 24, 2013.

- ^ "Table 61. Virginia – Race and Hispanic Origin: 1790 to 1990" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on March 27, 2010.

- ^ "African Americans". Handbook of Texas. Retrieved on December 17, 2011.

- ^ Maxine D. Rogers, et al., Documented History of the Incident Which Occurred at Rosewood, Florida in January 1923, December 1993, p. 5 "Rosewood". Archived from the original on May 15, 2008. Retrieved May 1, 2008., March 28, 2008

- ^ a b William H. Frey, "The New Great Migration: Black Americans' Return to the South, 1965–2000", The Brookings Institution, May 2004, pp. 1–5 "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on April 28, 2008. Retrieved May 19, 2008.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link), accessed March 19, 2008

Further reading

- Black, Merle, and Earl Black. "Deep South politics: the enduring racial division in national elections". .

- Brown, D. Clayton. King Cotton: A Cultural, Political, and Economic History since 1945 (University Press of Mississippi, 2011) 440 pp. ISBN 978-1-60473-798-1

- Davis, Allison. Deep South: A Social Anthropological Study of Caste and Class (1941) classic case study from the late 1930s

- Dollard, John. Caste and Class in a Southern Town (1941), a classic case study

- Fite, Gilbert C. Cotton fields no more: Southern agriculture, 1865–1980 (University Press of Kentucky, 2015).

- Gulley, Harold E. "Women and the lost cause: Preserving a Confederate identity in the American Deep South". Journal of historical geography 19.2 (1993): 125–141.

- Harris, J. William. Deep Souths: Delta, Piedmont, and Sea Island Society in the Age of Segregation (2003)

- Hughes, Dudley J. Oil in the Deep South: A History of the Oil Business in Mississippi, Alabama, and Florida, 1859–1945 (University Press of Mississippi, 1993).

- Key, V.O. Southern Politics in State and Nation (1951) classic political analysis, state by state. online free to borrow

- Kirby, Jack Temple. Rural Worlds Lost: The American South, 1920–1960 (Louisiana State University Press, 1986) major scholarly survey with detailed bibliography; online free to borrow.

- Lang, Clarence. "Locating the civil rights movement: An essay on the Deep South, Midwest, and border South in Black Freedom Studies". Journal of Social History 47.2 (2013): 371–400. Online

- Pierce, Neal R. The Deep South States of America: People, Politics, and Power in the Seven States of the Deep South (1974) in-depth study of politics and issues, state by state

- Rogers, William Warren, et al. Alabama: The history of a deep south state (University of Alabama Press, 2018).

- Roller, David C. and Robert W. Twyman, eds. The Encyclopedia of Southern History (Louisiana State University Press, 1979)

- Rothman, Adam. Slave Country: American Expansion and the Origins of the Deep South (2007)

- Thornton, J. Mills. Politics and power in a slave society: Alabama, 1800–1860 (1978) online free to borrow

- Vance, Rupert B. Regionalism and the South (UNC Press Books, 1982).

Primary sources

- Carson, Clayborne et al. eds. The Eyes on the Prize Civil Rights Reader: Documents, Speeches, and Firsthand Accounts from the Black Freedom Struggle (Penguin, 1991), 784pp.

- Johnson, Charles S. Statistical atlas of southern counties: listing and analysis of socio-economic indices of 1104 southern counties (1941). excerpt

- Raines, Howell, ed. My soul is rested: Movement days in the deep south remembered (Penguin, 1983).