Deforestation

Deforestation or forest clearance is the removal and destruction of a

The direct cause of most deforestation is agriculture by far.

Deforestation results in habitat destruction which in turn leads to biodiversity loss. Deforestation also leads to extinction of animals and plants, changes to the local climate, and displacement of indigenous people who live in forests. Deforested regions often also suffer from other environmental problems such as desertification and soil erosion.

Another problem is that deforestation reduces the uptake of carbon dioxide (carbon sequestration) from the atmosphere. This reduces the potential of forests to assist with climate change mitigation. The role of forests in capturing and storing carbon and mitigating climate change is also important for the agricultural sector.[12] The reason for this linkage is because the effects of climate change on agriculture pose new risks to global food systems.[12]

Definition

Deforestation is defined as the conversion of forest to other land uses (regardless of whether it is human-induced).[13]

Deforestation and forest area net change are not the same: the latter is the sum of all forest losses (deforestation) and all forest gains (forest expansion) in a given period. Net change, therefore, can be positive or negative, depending on whether gains exceed losses, or vice versa.[13]

Current status

The FAO estimates that the global forest carbon stock has decreased 0.9%, and tree cover 4.2% between 1990 and 2020.[14]: 16, 52

| Region | 1990 | 2020 |

|---|---|---|

| Europe (including Russia) | 158.7 | 172.4 |

| North America | 136.6 | 140.0 |

| Africa | 94.3 | 80.9 |

| South and Southeast Asia combined | 45.8 | 41.5 |

| Oceania | 33.4 | 33.1 |

| Central America | 5.0 | 4.1 |

| South America | 161.8 | 144.8 |

As of 2019 there is still disagreement about whether the global forest is shrinking or not: "While above-ground biomass carbon stocks are estimated to be declining in the tropics, they are increasing globally due to increasing stocks in temperate and boreal forest.[15]: 385

Deforestation is more extreme in tropical and subtropical forests in emerging economies. More than half of all plant and land animal species in the world live in tropical forests.[20] As a result of deforestation, only 6.2 million square kilometres (2.4 million square miles) remain of the original 16 million square kilometres (6 million square miles) of tropical rainforest that formerly covered the Earth.[18] An area the size of a football pitch is cleared from the Amazon rainforest every minute, with 136 million acres (55 million hectares) of rainforest cleared for animal agriculture overall.[21][failed verification] More than 3.6 million hectares of virgin tropical forest was lost in 2018.[22]

The global annual net loss of trees is estimated to be approximately 10 billion.

An analysis of global deforestation patterns in 2021 showed that patterns of trade, production, and consumption drive deforestation rates in complex ways. While the location of deforestation can be mapped, it does not always match where the commodity is consumed. For example, consumption patterns in

In 2023, the

Rates of deforestation

Global deforestation[30] sharply accelerated around 1852.[31][32] As of 1947, the planet had 15 million to 16 million km2 (5.8 million to 6.2 million sq mi) of mature tropical forests,[33] but by 2015, it was estimated that about half of these had been destroyed.[34][20][35] Total land coverage by tropical rainforests decreased from 14% to 6%. Much of this loss happened between 1960 and 1990, when 20% of all tropical rainforests were destroyed. At this rate, extinction of such forests is projected to occur by the mid-21st century.[36]

In the early 2000s, some scientists predicted that unless significant measures (such as seeking out and protecting old growth forests that have not been disturbed)

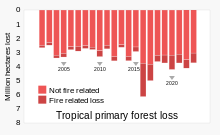

Estimates vary widely as to the extent of deforestation in the tropics.[5][6] In 2019, the world lost nearly 12 million hectares of tree cover. Nearly a third of that loss, 3.8 million hectares, occurred within humid tropical primary forests, areas of mature rainforest that are especially important for biodiversity and carbon storage. This is equivalent to losing an area of primary forest the size of a football pitch every six seconds.[7][8]

Rates of change

A 2002 analysis of satellite imagery suggested that the rate of deforestation in the humid tropics (approximately 5.8 million hectares per year) was roughly 23% lower than the most commonly quoted rates.[40] A 2005 report by the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) estimated that although the Earth's total forest area continued to decrease at about 13 million hectares per year, the global rate of deforestation had been slowing.[41][42] On the other hand, a 2005 analysis of satellite images reveals that deforestation of the Amazon rainforest is twice as fast as scientists previously estimated.[43][44]

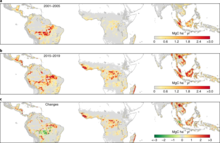

From 2010 to 2015, worldwide forest area decreased by 3.3 million ha per year, according to FAO. During this five-year period, the biggest forest area loss occurred in the tropics, particularly in South America and Africa. Per capita forest area decline was also greatest in the tropics and subtropics but is occurring in every climatic domain (except in the temperate) as populations increase.[45]

An estimated 420 million ha of forest has been lost worldwide through deforestation since 1990, but the rate of forest loss has declined substantially. In the most recent five-year period (2015–2020), the annual rate of deforestation was estimated at 10 million ha, down from 12 million ha in 2010–2015.[13]

Africa had the largest annual rate of net forest loss in 2010–2020, at 3.9 million ha, followed by South America, at 2.6 million ha. The rate of net forest loss has increased in Africa in each of the three decades since 1990. It has declined substantially in South America, however, to about half the rate in 2010–2020 compared with 2000–2010. Asia had the highest net gain of forest area in 2010–2020, followed by Oceania and Europe. Nevertheless, both Europe and Asia recorded substantially lower rates of net gain in 2010–2020 than in 2000–2010. Oceania experienced net losses of forest area in the decades 1990–2000 and 2000–2010.[13]

Some claim that rainforests are being destroyed at an ever-quickening pace.[47] The London-based Rainforest Foundation notes that "the UN figure is based on a definition of forest as being an area with as little as 10% actual tree cover, which would therefore include areas that are actually savanna-like ecosystems and badly damaged forests".[48] Other critics of the FAO data point out that they do not distinguish between forest types,[49] and that they are based largely on reporting from forestry departments of individual countries,[50] which do not take into account unofficial activities like illegal logging.[51] Despite these uncertainties, there is agreement that destruction of rainforests remains a significant environmental problem.

The rate of net forest loss declined from 7.8 million ha per year in the decade 1990–2000 to 5.2 million ha per year in 2000–2010 and 4.7 million ha per year in 2010–2020. The rate of decline of net forest loss slowed in the most recent decade due to a reduction in the rate of forest expansion.[13]

Reforestation and afforestation

In many parts of the world, especially in East Asian countries, reforestation and afforestation are increasing the area of forested lands.[52] The amount of forest has increased in 22 of the world's 50 most forested nations. Asia as a whole gained 1 million hectares of forest between 2000 and 2005. Tropical forest in El Salvador expanded more than 20% between 1992 and 2001. Based on these trends, one study projects that global forestation will increase by 10%—an area the size of India—by 2050.[53] 36% of globally planted forest area is in East Asia - around 950,000 square kilometers. From those 87% are in China.[54]

Status by region

Rates of deforestation vary around the world. Up to 90% of West Africa's coastal rainforests have disappeared since 1900.[55] Madagascar has lost 90% of its eastern rainforests.[56][57] In South Asia, about 88% of the rainforests have been lost.[58]

Mexico, India, the Philippines, Indonesia, Thailand, Burma, Malaysia, Bangladesh, China, Sri Lanka, Laos, Nigeria, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Liberia, Guinea, Ghana and the Ivory Coast, have lost large areas of their rainforest.[59][60]

Much of what remains of the world's rainforests is in the

As of 2007, less than 50% of Haiti's forests remained.[72]

From 2015 to 2019, the rate of deforestation in the Democratic Republic of the Congo doubled.[73] In 2021, deforestation of the Congolese rainforest increased by 5%.[74]

The

In 2011, Conservation International listed the top 10 most endangered forests, characterized by having all lost 90% or more of their original habitat, and each harboring at least 1500 endemic plant species (species found nowhere else in the world).[75]

As of 2015[update], it is estimated that 70% of the world's forests are within one kilometer of a forest edge, where they are most prone to human interference and destruction.[76][77]

Top 10 Most Endangered Forests in 2011[75] Endangered forest Region Remaining habitat Predominate vegetation type Notes Indo-Burma Asia-Pacific 5% Tropical and subtropical moist broadleaf forests Rivers, floodplain wetlands, mangrove forests. Burma, Thailand, Laos, Vietnam, Cambodia, India.[78] New Caledonia Asia-Pacific 5% Tropical and subtropical moist broadleaf forests See note for region covered.[79] Sundaland Asia-Pacific 7% Tropical and subtropical moist broadleaf forests Western half of the Indo-Malayan archipelago including southern Borneo and Sumatra.[80] Philippines Asia-Pacific 7% Tropical and subtropical moist broadleaf forests Forests over the entire country including 7,100 islands.[81] Atlantic Forest South America 8% Tropical and subtropical moist broadleaf forests Forests along Brazil's Atlantic coast, extends to parts of Paraguay, Argentina and Uruguay.[82] Mountains of Southwest China Asia-Pacific 8% Temperate coniferous forest See note for region covered.[83] California Floristic Province North America 10% Tropical and subtropical dry broadleaf forests See note for region covered.[84] Coastal Forests of Eastern AfricaAfrica 10% Tropical and subtropical moist broadleaf forests Mozambique, Tanzania, Kenya, Somalia.[85] Madagascar & Indian Ocean Islands Africa 10% Tropical and subtropical moist broadleaf forests Eastern AfromontaneAfrica 11% Tropical and subtropical moist broadleaf forests

Montane grasslands and shrublandsForests scattered along the eastern edge of Africa, from Saudi Arabia in the north to Zimbabwe in the south.[87]

By country

Deforestation in particular countries:

Causes

The vast majority of agricultural activity resulting in deforestation is subsidized by government tax revenue.[88] Disregard of ascribed value, lax forest management, and deficient environmental laws are some of the factors that lead to large-scale deforestation.

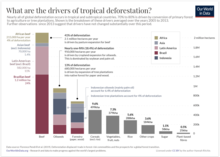

The types of drivers vary greatly depending on the region in which they take place. The regions with the greatest amount of deforestation for livestock and row crop agriculture are Central and South America, while commodity crop deforestation was found mainly in Southeast Asia. The region with the greatest forest loss due to shifting agriculture was sub-Saharan Africa.[89]

Agriculture

The overwhelming direct cause of deforestation is agriculture.

More than 80% of deforestation was attributed to agriculture in 2018.

Most deforestation also occurs in tropical regions. The estimated amount of total land mass used by agriculture is around 38%.[91]

Since 1960, roughly 15% of the Amazon has been removed with the intention of replacing the land with agricultural practices.[92] It is no coincidence that Brazil has recently become the world's largest beef exporter at the same time that the Amazon rainforest is being clear cut.[93]

Another prevalent method of agricultural deforestation is slash-and-burn agriculture, which was primarily used by subsistence farmers in tropical regions but has now become increasingly less sustainable. The method does not leave land for continuous agricultural production but instead cuts and burns small plots of forest land which are then converted into agricultural zones. The farmers then exploit the nutrients in the ashes of the burned plants.[94][95] As well as, intentionally set fires can possibly lead to devastating measures when unintentionally spreading fire to more land, which can result in the destruction of the protective canopy.[96]

The repeated cycle of low yields and shortened fallow periods eventually results in less vegetation being able to grow on once burned lands and a decrease in average soil biomass.[97] In small local plots sustainability is not an issue because of longer fallow periods and lesser overall deforestation. The relatively small size of the plots allowed for no net input of CO2 to be released.[98]

Livestock ranching

Consumption and production of beef is the primary driver of deforestation in the Amazon, with around 80% of all converted land being used to rear cattle.[99][100] 91% of Amazon land deforested since 1970 has been converted to cattle ranching.[101][102]

The cattle industry is responsible for a significant amount of

Wood industry

A large contributing factor to deforestation is the lumber industry. A total of almost 4 million hectares (9.9×106 acres) of timber,[107] or about 1.3% of all forest land, is harvested each year. In addition, the increasing demand for low-cost timber products only supports the lumber company to continue logging.[108]

Experts do not agree on whether industrial logging is an important contributor to global deforestation.[109][110] Some argue that poor people are more likely to clear forest because they have no alternatives, others that the poor lack the ability to pay for the materials and labour needed to clear forest.[109]

Economic development

Other causes of contemporary deforestation may include corruption of government institutions,[111][112][113] the inequitable distribution of wealth and power,[114] population growth[115] and overpopulation,[116][117] and urbanization.[118][119] The impact of population growth on deforestation has been contested. One study found that population increases due to high fertility rates were a primary driver of tropical deforestation in only 8% of cases.[120] In 2000 the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) found that "the role of population dynamics in a local setting may vary from decisive to negligible", and that deforestation can result from "a combination of population pressure and stagnating economic, social and technological conditions".[115]

Globalization is often viewed as another root cause of deforestation,[121][122] though there are cases in which the impacts of globalization (new flows of labor, capital, commodities, and ideas) have promoted localized forest recovery.[123]

The degradation of forest ecosystems has also been traced to economic incentives that make forest conversion appear more profitable than forest conservation.[124] Many important forest functions have no markets, and hence, no economic value that is readily apparent to the forests' owners or the communities that rely on forests for their well-being.[124] From the perspective of the developing world, the benefits of forest as carbon sinks or biodiversity reserves go primarily to richer developed nations and there is insufficient compensation for these services. Developing countries feel that some countries in the developed world, such as the United States of America, cut down their forests centuries ago and benefited economically from this deforestation, and that it is hypocritical to deny developing countries the same opportunities, i.e. that the poor should not have to bear the cost of preservation when the rich created the problem.[125]

Some commentators have noted a shift in the drivers of deforestation over the past 30 years.[126] Whereas deforestation was primarily driven by subsistence activities and government-sponsored development projects like transmigration in countries like Indonesia and colonization in Latin America, India, Java, and so on, during the late 19th century and the first half of the 20th century, by the 1990s the majority of deforestation was caused by industrial factors, including extractive industries, large-scale cattle ranching, and extensive agriculture.[127] Since 2001, commodity-driven deforestation, which is more likely to be permanent, has accounted for about a quarter of all forest disturbance, and this loss has been concentrated in South America and Southeast Asia.[128]

As the human population grows, new homes, communities, and expansions of cities will occur, leading to an increase in roads to connect these communities. Rural roads promote economic development but also facilitate deforestation.[129] About 90% of the deforestation has occurred within 100 km of roads in most parts of the Amazon.[130]

The

Some have argued that deforestation trends may follow a

Mining

The importance of mining as a cause of deforestation increased quickly in the beginning the 21st century, among other because of increased demand for minerals. The direct impact of mining is relatively small, but the indirect impacts are much more significant. More than a third of the earth's forests are possibly impacted, at some level and in the years 2001–2021, "755,861 km2... ...had been deforested by causes indirectly related to mining activities alongside other deforestation drivers (based on data from WWF)"[135]

Climate change

Another cause of deforestation is due to the effects of climate change: More wildfires,[137] insect outbreaks, invasive species, and more frequent extreme weather events (such as storms) are factors that increase deforestation.[138]

A study suggests that "tropical, arid and temperate forests are experiencing a significant decline in resilience, probably related to increased water limitations and climate variability" which may shift ecosystems towards critical transitions and ecosystem collapses.[136] By contrast, "boreal forests show divergent local patterns with an average increasing trend in resilience, probably benefiting from warming and CO2 fertilization, which may outweigh the adverse effects of climate change".[136] It has been proposed that a loss of resilience in forests "can be detected from the increased temporal autocorrelation (TAC) in the state of the system, reflecting a decline in recovery rates due to the critical slowing down (CSD) of system processes that occur at thresholds".[136]

23% of tree cover losses result from wildfires and climate change increase their frequency and power.

Military causes

Operations in war can also cause deforestation. For example, in the 1945 Battle of Okinawa, bombardment and other combat operations reduced a lush tropical landscape into "a vast field of mud, lead, decay and maggots".[142]

Deforestation can also result from the intentional

Impacts

On atmosphere and climate

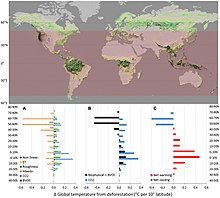

Deforestation is a major contributor to

According to a review, north of 50°N, large scale deforestation leads to an overall net global cooling; but deforestation in the tropics leads to substantial warming: not just due to CO2 impacts, but also due to other biophysical mechanisms (making carbon-centric metrics inadequate). Moreover, it suggests that standing tropical forests help cool the average global temperature by more than 1 °C.[158][151]

The incineration and burning of forest plants to clear land releases large amounts of CO2, which contributes to global warming.[159] Scientists also state that tropical deforestation releases 1.5 billion tons of carbon each year into the atmosphere.[160]

Carbon sink or source

A study suggests logged and structurally degraded tropical forests are carbon sources for at least a decade – even when recovering[clarification needed] – due to larger carbon losses from soil organic matter and deadwood, indicating that the tropical forest carbon sink (at least in South Asia) "may be much smaller than previously estimated", contradicting that "recovering logged and degraded tropical forests are net carbon sinks".[161]

On the environment

According to a 2020 study, if deforestation continues at current rates it can trigger a total or almost total extinction of humanity in the next 20 to 40 years. They conclude that "from a statistical point of view . . . the probability that our civilisation survives itself is less than 10% in the most optimistic scenario." To avoid this collapse, humanity should pass from a civilization dominated by the economy to "cultural society" that "privileges the interest of the ecosystem above the individual interest of its components, but eventually in accordance with the overall communal interest."[163][164]

Changes to the water cycle

The

Shrinking forest cover lessens the landscape's capacity to intercept, retain and transpire precipitation. Instead of trapping precipitation, which then percolates to groundwater systems, deforested areas become sources of surface water runoff, which moves much faster than subsurface flows. Forests return most of the water that falls as precipitation to the atmosphere by transpiration. In contrast, when an area is deforested, almost all precipitation is lost as run-off.[168] That quicker transport of surface water can translate into flash flooding and more localized floods than would occur with the forest cover. Deforestation also contributes to decreased evapotranspiration, which lessens atmospheric moisture which in some cases affects precipitation levels downwind from the deforested area, as water is not recycled to downwind forests, but is lost in runoff and returns directly to the oceans. According to one study, in deforested north and northwest China, the average annual precipitation decreased by one third between the 1950s and the 1980s.[169]

Trees, and plants in general, affect the water cycle significantly:[170]

- their canopies intercept a proportion of precipitation, which is then evaporated back to the atmosphere (canopy interception);

- their litter, stems and trunks slow down surface runoff;

- their roots create macropores – large conduits – in the soil that increase infiltration of water;

- they contribute to terrestrial evaporation and reduce soil moisture via transpiration;

- their litter and other organic residue change soil properties that affect the capacity of soil to store water.

- their leaves control the humidity of the atmosphere by transpiring. 99% of the water absorbed by the roots moves up to the leaves and is transpired.[171]

As a result, the presence or absence of trees can change the quantity of water on the surface, in the soil or groundwater, or in the atmosphere. This in turn changes erosion rates and the availability of water for either ecosystem functions or human services. Deforestation on lowland plains moves cloud formation and rainfall to higher elevations.[172]

The forest may have little impact on flooding in the case of large rainfall events, which overwhelm the storage capacity of forest soil if the soils are at or close to saturation.

Tropical rainforests produce about 30% of Earth's fresh water.[173]

Deforestation disrupts normal weather patterns creating hotter and drier weather thus increasing drought, desertification, crop failures, melting of the polar ice caps, coastal flooding and displacement of major vegetation regimes.[174]

Soil erosion

Due to surface

Deforestation in China's Loess Plateau many years ago has led to soil erosion; this erosion has led to valleys opening up. The increase of soil in the runoff causes the Yellow River to flood and makes it yellow-colored.[176]

Greater erosion is not always a consequence of deforestation, as observed in the southwestern regions of the US. In these areas, the loss of grass due to the presence of trees and other shrubbery leads to more erosion than when trees are removed.[176]

Soils are reinforced by the presence of trees, which secure the soil by binding their roots to soil bedrock. Due to deforestation, the removal of trees causes sloped lands to be more susceptible to landslides.[170]

Other changes to the soil

Clearing forests changes the environment of the

Changes in soil properties could turn the soil itself into a

Biodiversity loss

Deforestation on a human scale results in decline in biodiversity,[180] and on a natural global scale is known to cause the extinction of many species.[181][182] The removal or destruction of areas of forest cover has resulted in a degraded environment with reduced biodiversity.[117] Forests support biodiversity, providing habitat for wildlife;[183] moreover, forests foster medicinal conservation.[184] With forest biotopes being irreplaceable source of new drugs (such as taxol), deforestation can destroy genetic variations (such as crop resistance) irretrievably.[185]

Since the tropical rainforests are the most diverse

It has been estimated that 137 plant, animal and insect species go extinct every day due to rainforest deforestation, which equates to 50,000 species a year.

Scientific understanding of the process of extinction is insufficient to accurately make predictions about the impact of deforestation on biodiversity.

In 2012, a study of the Brazilian Amazon predicts that despite a lack of extinctions thus far, up to 90 percent of predicted extinctions will finally occur in the next 40 years.[200]

Oxygen-supply misconception

Rainforests are widely believed by lay persons to contribute a significant amount of the world's oxygen,

On human health

Infectious diseases

The degradation and loss of forests disrupts nature's balance.[12] Indeed, deforestation eliminates a great number of species of plants and animals which also often results in an increase in disease,[204] and exposure of people to zoonotic diseases.[12][205][206][207] Deforestation can also create a path for non-native species to flourish such as certain types of snails, which have been correlated with an increase in schistosomiasis cases.[204][208]

Forest-associated diseases include malaria, Chagas disease (also known as American trypanosomiasis), African trypanosomiasis (sleeping sickness), leishmaniasis, Lyme disease, HIV and Ebola.[12] The majority of new infectious diseases affecting humans, including the SARS-CoV-2 virus that caused the COVID-19 pandemic, are zoonotic and their emergence may be linked to habitat loss due to forest area change and the expansion of human populations into forest areas, which both increase human exposure to wildlife.[12]

Deforestation is occurring all over the world and has been coupled with an increase in the occurrence of disease outbreaks. In

Another pathway through which deforestation affects disease is the relocation and dispersion of disease-carrying hosts. This disease emergence pathway can be called "

Deforestation reduces safe working hours for millions of people in the tropics, especially for those performing heavy labour outdoors. Continued global heating and forest loss is expected to amplify these impacts, reducing work hours for vulnerable groups even more.[216] A study conducted from 2002 to 2018 also determined that the increase in temperature as a result of climate change, and the lack of shade due to deforestation, has increased the mortality rate of workers in Indonesia.[217]

A link between deforestation and infant mortality was found in Indonesia as well. The study shows documentation of deforestation and pregnancy order,[218] as children born from first pregnancies face higher mortality risks due to in-utero exposure. The study's results suggest that women during their first pregnancy could have been affected by deforestation-induced malaria.[218] It has been affirmed that in preserved regions, likely reasons including commercial activity, perinatal health care, alongside air pollution are not identifiable triggers of the weighty impression left by deforestation on newborn fatality.[218]

According to the World Economic Forum, 31% of emerging diseases are linked to deforestation.[219] A publication by the United Nations Environment Programme in 2016 found that deforestation, climate change, and livestock agriculture are among the main causes that increase the risk of zoonotic diseases, that is diseases that pass from animals to humans.[220]

COVID-19 pandemic

Scientists have linked the

On the economy and agriculture

This section needs to be updated. The reason given is: cites are very old. (June 2020) |

Economic losses due to deforestation in Brazil could reach around 317 billion dollars per year, approximately 7 times higher in comparison to the cost of all commodities produced through deforestation.[223]

The forest products industry is a large part of the economy in both developed and developing countries. Short-term economic gains made by conversion of forest to agriculture, or

The resilience of human food systems and their capacity to adapt to future change is linked to biodiversity – including dryland-adapted shrub and tree species that help combat desertification, forest-dwelling insects, bats and bird species that pollinate crops, trees with extensive root systems in

Monitoring

There are multiple methods that are appropriate and reliable for reducing and monitoring deforestation. One method is the "visual interpretation of aerial photos or satellite imagery that is labor-intensive but does not require high-level training in computer image processing or extensive computational resources".[130] Another method includes hot-spot analysis (that is, locations of rapid change) using expert opinion or coarse resolution satellite data to identify locations for detailed digital analysis with high resolution satellite images.[130] Deforestation is typically assessed by quantifying the amount of area deforested, measured at the present time. From an environmental point of view, quantifying the damage and its possible consequences is a more important task, while conservation efforts are more focused on forested land protection and development of land-use alternatives to avoid continued deforestation.[130] Deforestation rate and total area deforested have been widely used for monitoring deforestation in many regions, including the Brazilian Amazon deforestation monitoring by INPE.[160] A global satellite view is available, an example of land change science monitoring of land cover over time.[225][226]

Satellite imaging has become crucial in obtaining data on levels of deforestation and reforestation.

Greenpeace has mapped out the forests that are still intact[228] and published this information on the internet.[229] World Resources Institute in turn has made a simpler thematic map[230] showing the amount of forests present just before the age of man (8000 years ago) and the current (reduced) levels of forest.[231]

Control

International, national and subnational policies

Policies for forest protection include information and education programs, economic measures to increase revenue returns from authorized activities and measures to increase effectiveness of "forest technicians and forest managers".[232] Poverty and agricultural rent were found to be principal factors leading to deforestation.[233] Contemporary domestic and foreign political decision-makers could possibly create and implement policies whose outcomes ensure that economic activities in critical forests are consistent with their scientifically ascribed value for ecosystem services, climate change mitigation and other purposes.

Such policies may use and organize the development of complementary technical and economic means – including for lower levels of beef production, sales and consumption (which would also have major benefits for

In 2022 the

But unfortunately, as the report Bankrolling ecosystem destruction shows,[245] this regulation of product imports is not enough. The European financial sector is investing billions of euros in the destruction of nature. Banks do not respond positively to requests to stop this, which is why the report calls for European regulation in this area to be tightened and for banks to be banned from continuing to finance deforestation.[246]

International pledges

In 2014, about 40 countries signed the New York Declaration on Forests, a voluntary pledge to halve deforestation by 2020 and end it by 2030. The agreement was not legally binding, however, and some key countries, such as Brazil, China, and Russia, did not sign onto it. As a result, the effort failed, and deforestation increased from 2014 to 2020.[247][248]

In November 2021, 141 countries (with around 85% of the world's

The 2021 Glasgow agreement improved on the New York Declaration by now including Brazil and many other countries that did not sign the 2014 agreement.[248][249] Some key nations with high rates of deforestation (including Malaysia, Cambodia, Laos, Paraguay, and Myanmar) have not signed the Glasgow Declaration.[249] Like the earlier agreement, the Glasgow Leaders' Declaration was entered into outside the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change and is thus not legally binding.[249]

In November 2021, the EU executive outlined a draft law requiring companies to prove that the agricultural commodities beef, wood, palm oil, soy, coffee and cocoa destined for the EU's 450 million consumers were not linked to deforestation.[251] In September 2022, the EU Parliament supported and strengthened the plan from the EU’s executive with 453 votes to 57.[252]

In 2018 the biggest palm oil trader, Wilmar, decided to control its suppliers to avoid deforestation[253][additional citation(s) needed]

In 2021, over 100 world leaders, representing countries containing more than 85% of the world's forests, committed to halt and reverse deforestation and land degradation by 2030.[254]

Land rights

Indigenous communities have long been the frontline of resistance against deforestation.[255] Transferring rights over land from public domain to its indigenous inhabitants is argued to be a cost-effective strategy to conserve forests.[256] This includes the protection of such rights entitled in existing laws, such as India's Forest Rights Act.[256] The transferring of such rights in China, perhaps the largest land reform in modern times, has been argued to have increased forest cover.[257] In Brazil, forested areas given tenure to indigenous groups have even lower rates of clearing than national parks.[257]

Community concessions in the Congolian rainforests have significantly less deforestation as communities are incentivized to manage the land sustainably, even reducing poverty.[258]

Forest management

Efforts to stop or slow deforestation have been attempted for many centuries because it has long been known that deforestation can cause environmental damage sufficient in some cases to cause societies to collapse. In

In the areas where "slash-and-burn" is practiced, switching to "slash-and-char" would prevent the rapid deforestation and subsequent degradation of soils. The biochar thus created, given back to the soil, is not only a durable carbon sequestration method, but it also is an extremely beneficial amendment to the soil. Mixed with biomass it brings the creation of terra preta, one of the richest soils on the planet and the only one known to regenerate itself.

Sustainable forest management

Certification, as provided by global certification systems such as Programme for the Endorsement of Forest Certification and Forest Stewardship Council, contributes to tackling deforestation by creating market demand for timber from sustainably managed forests. According to the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), "A major condition for the adoption of sustainable forest management is a demand for products that are produced sustainably and consumer willingness to pay for the higher costs entailed. [...] By promoting the positive attributes of forest products from sustainably managed forests, certification focuses on the demand side of environmental conservation."[262]

Financial compensations for reducing emissions from deforestation

Main international organizations including the United Nations and the World Bank, have begun to develop programs aimed at curbing deforestation. The blanket term Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation (REDD) describes these sorts of programs, which use direct monetary or other incentives to encourage developing countries to limit and/or roll back deforestation. Funding has been an issue, but at the

Significant work is underway on tools for use in monitoring developing countries' adherence to their agreed REDD targets. These tools, which rely on remote forest monitoring using satellite imagery and other data sources, include the Center for Global Development's FORMA (Forest Monitoring for Action) initiative[265] and the Group on Earth Observations' Forest Carbon Tracking Portal.[266] Methodological guidance for forest monitoring was also emphasized at COP-15.[267] The environmental organization Avoided Deforestation Partners leads the campaign for development of REDD through funding from the U.S. government.[268]

History

Prehistory

The

Rainforests once covered 14% of the earth's land surface; now they cover a mere 6% and experts estimate that the last remaining rainforests could be consumed in less than 40 years.[269] Small scale deforestation was practiced by some societies for tens of thousands of years before the beginnings of civilization. agriculture.

The

Evidence of deforestation has been found in

Pre-industrial history

Just as archaeologists have shown that prehistoric farming societies had to cut or burn forests before planting, documents and artifacts from early civilizations often reveal histories of deforestation. Some of the most dramatic are eighth century BCE Assyrian reliefs depicting logs being floated downstream from conquered areas to the less forested capital region as spoils of war. Ancient Chinese texts make clear that some areas of the Yellow River valley had already destroyed many of their forests over 2000 years ago and had to plant trees as crops or import them from long distances.[275] In South China much of the land came to be privately owned and used for the commercial growing of timber.[276]

Three regional studies of historic erosion and alluviation in

Easter Island has suffered from heavy soil erosion in recent centuries, aggravated by agriculture and deforestation.[280] The disappearance of the island's trees seems to coincide with a decline of its civilization around the 17th and 18th century. Scholars have attributed the collapse to deforestation and over-exploitation of all resources.[281][282]

The famous silting up of the harbor for Bruges, which moved port commerce to Antwerp, also followed a period of increased settlement growth (and apparently of deforestation) in the upper river basins. In early medieval Riez in upper Provence, alluvial silt from two small rivers raised the riverbeds and widened the floodplain, which slowly buried the Roman settlement in alluvium and gradually moved new construction to higher ground; concurrently the headwater valleys above Riez were being opened to pasturage.[283]

A typical

With most of the population remaining active in (or indirectly dependent on) the agricultural sector, the main pressure in most areas remained land clearing for crop and cattle farming. Enough wild green was usually left standing (and partially used, for example, to collect firewood, timber and fruits, or to graze pigs) for wildlife to remain viable. The elite's (nobility and higher clergy) protection of their own hunting privileges and game often protected significant woodland.[285]

Major parts in the spread (and thus more durable growth) of the population were played by monastical 'pioneering' (especially by the

From 1100 to 1500 AD, significant deforestation took place in Western Europe as a result of the expanding human population.[289] The large-scale building of wooden sailing ships by European (coastal) naval owners since the 15th century for exploration, colonisation, slave trade, and other trade on the high seas, consumed many forest resources and became responsible for the introduction of numerous bubonic plague outbreaks in the 14th century. Piracy also contributed to the over harvesting of forests, as in Spain. This led to a weakening of the domestic economy after Columbus' discovery of America, as the economy became dependent on colonial activities (plundering, mining, cattle, plantations, trade, etc.)[285]

The massive use of

19th and 20th centuries

Steamboats

In the 19th century, introduction of

Society and culture

Different cultures of different places in the world have different interpretations of the actions of the cutting down of trees. For example, in

See also

- Clearcutting

- Clearing (geography)

- Defaunation

- Ecocide

- Deforestation by region

- Desertification

- Forestry

- Forest transition

- Illegal logging

- Intact forest landscape

- International Year of Forests

- Land degradation

- Land use, land-use change and forestry

- Mountaintop removal

- Proforestation

- Slash-and-burn

- Slash-and-char

- Stranded assets in the agriculture and forestry sector

References

- ^ SAFnet Dictionary|Definition For [deforestation] Archived 25 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine. Dictionary of forestry.org (29 July 2008). Retrieved 15 May 2011.

- ^ Deforestation | Threats | WWF. Worldwildlife.org. Retrieved 13 November 2016.

- ^ Ritchie, Hannah; Roser, Max (9 February 2021). "Forests and Deforestation". Our World in Data.

- ^ "On Water". European Investment Bank. Retrieved 13 October 2020.

- ^ ISBN 978-3-642-00492-6.

- ^ a b Watson, Robert T.; Noble, Ian R.; Bolin, Bert; Ravindranath, N. H.; Verardo, David J.; Dokken, David J. (2000). Land Use, Land-Use Change, and Forestry (Report). Cambridge University Press.

- ^ a b c Guy, Jack; Ehlinger, Maija (2 June 2020). "The world lost a football pitch-sized area of tropical forest every six seconds in 2019". CNN. Retrieved 2 June 2020.

- ^ a b Weisse, Mikaela; Goldman, Elizabeth Dow (2 June 2020). "We Lost a Football Pitch of Primary Rainforest Every 6 Seconds in 2019". World Resources Institute. Retrieved 4 June 2020.

- ^ a b c "Investment and financial flows to address climate change" (PDF). unfccc.int. UNFCCC. 2007. p. 81. Archived (PDF) from the original on 10 May 2008.

- ^ a b "Agriculture is the direct driver for worldwide deforestation". ScienceDaily. Retrieved 29 April 2018.

- ^ a b "Forest Conversion". WWF. Retrieved 22 October 2020.

- ^ S2CID 241416114.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Global Forest Resource Assessment 2020". www.fao.org. Retrieved 20 September 2020.

- ^ a b FAO (2020). "Global Forest Resources Assessment" (PDF).

- ^ IPCC (2019a). "Climate Change and Land: an IPCC special report on climate change, desertification, land degradation, sustainable land management, food security, and greenhouse gas fluxes in terrestrial ecosystems. Chapter 4. Land Degradation" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 December 2019.

- ^ "The causes of deforestation". Eniscuola. Retrieved 6 August 2020.

- ^ "The five: areas of deforestation". The Guardian. 24 November 2019. Retrieved 5 June 2020.

- ^ a b "Facts About Rainforests" Archived 22 October 2015 at the Wayback Machine. The Nature Conservancy. Retrieved 19 October 2015.

- PMID 29853680.

- ^ a b Rainforest Facts Archived 22 October 2015 at the Wayback Machine. Nature.org (1 November 2016). Retrieved 13 November 2016.

- ^ "Amazon Destruction". Mongabay. Retrieved 13 December 2017.

- ^ Human society under urgent threat from loss of Earth's natural life. Scientists reveal 1 million species at risk of extinction in damning UN report 6 May 2019 Guardian [1]

- ^ "Earth has 3 trillion trees but they're falling at alarming rate". Reuters. 2 September 2015. Retrieved 26 May 2020.

- ^ Carrington, Damian (4 July 2019). "Tree planting 'has mind-blowing potential' to tackle climate crisis". The Guardian. Retrieved 26 May 2020.

- ^ "Average westerner's eating habits lead to loss of four trees every year". the Guardian. 29 March 2021. Retrieved 19 April 2021.

- S2CID 232420306. Retrieved 19 April 2021.

- ^ Spring, Jake (4 April 2024). Dunham, Will (ed.). "Tropical forest loss eased in 2023 but threats remain, analysis shows". www.reuters.com. Retrieved 4 April 2024.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Steffen, Will; Sanderson, Angelina; Tyson, Peter; Jäger, Jill; et al. (2004). "Global Change and the Climate System / A Planet Under Pressure" (PDF). International Geosphere-Biosphere Programme (IGBP). pp. 131, 133. Archived (PDF) from the original on 19 March 2017.

Fig. 3.67(j): loss of tropical rainforest and woodland, as estimated for tropical Africa, Latin America and South and Southeast Asia.

- ^ "Deforestation and Forest Loss / Humanity destroyed one third of the world's forests by expanding agricultural land". Our World in Data (OWID). Archived from the original on 7 November 2022.

Data: Historical data on forests from Williams (2003) - Deforesting the Earth. Historical data on agriculture from The History Database of Global Environment (HYDE). Modern data from the FAO

- ^ Duke Press policy studies / Global deforestation and the nineteenth-century world economy / edited by Richard P. Tucker and J. F. Richards

- ^ ISBN 0-679-76811-4.

- ^ Map reveals extent of deforestation in tropical countries, guardian.co.uk, 1 July 2008.

- ^ a b Maycock, Paul F. Deforestation[permanent dead link]. WorldBookOnline.

- ^ Nunez, Christina (7 February 2019). "Deforestation and Its Effect on the Planet". National Geographic. Archived from the original on 17 January 2017. Retrieved 2 June 2020.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-312-42581-4.

- ^ ]

- ISBN 978-92-5-132581-0. Archived (PDF) from the original on 22 September 2023.)

{{cite book}}:|website=ignored (help - ^ Butler, Rhett A. (31 March 2021). "Global forest loss increases in 2020". Mongabay. Archived from the original on 1 April 2021. ● Mongabay publishing data from "Forest Loss / How much tree cover is lost globally each year?". research.WRI.org. World Resources Institute — Global Forest Review. 2023. Archived from the original on 2 August 2023.

- ^ a b "Forest Pulse: The Latest on the World's Forests". WRI.org. World Resources Institute. June 2023. Archived from the original on 27 June 2023. ● 2022 Global Forest Watch data quoted by McGrath, Matt; Poynting, Mark (27 June 2023). "Climate change: Deforestation surges despite pledges". BBC. Archived from the original on 29 June 2023.

- S2CID 46315941.

- ^ "Pan-tropical Survey of Forest Cover Changes 1980–2000". Forest Resources Assessment. Rome, Italy: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO).

- ^ Committee On Forestry. FAO (16 March 2001). Retrieved 29 August 2010.

- ^ Jha, Alok (21 October 2005). "Amazon rainforest vanishing at twice rate of previous estimates". The Guardian.

- ^ Satellite images reveal Amazon forest shrinking faster, csmonitor.com, 21 October 2005.

- ^ FAO. 2016. Global Forest Resources Assessment 2015. How are the world’s forests changing?

- ^ "Amazon Against the Clock: A Regional Assessment on Where and How to Protect 80% by 2025" (PDF). Amazon Watch. September 2022. p. 8. Archived (PDF) from the original on 10 September 2022.

Graphic 2: Current State of the Amazon by country, by percentage / Source: RAISG (Red Amazónica de Información Socioambiental Georreferenciada) Elaborated by authors.

- ^ Worldwatch: Wood Production and Deforestation Increase & Recent Content Archived 25 October 2008 at the Wayback Machine, Worldwatch Institute

- ^ a b Butler, Rhett A. (16 November 2005). "World deforestation rates and forest cover statistics, 2000–2005". mongabay.com.

- ^ The fear is that highly diverse habitats, such as tropical rainforest, are vanishing at a faster rate that is partly masked by the slower deforestation of less biodiverse, dry, open forests. Because of this omission, the most harmful impacts of deforestation (such as habitat loss) could be increasing despite a possible decline in the global rate of deforestation.

- ^ "Remote sensing versus self-reporting".

- ^ The World Bank estimates that 80% of logging operations are illegal in Bolivia and 42% in Colombia, while in Peru, illegal logging accounts for 80% of all logging activities. (World Bank (2004). Forest Law Enforcement.) (The Peruvian Environmental Law Society (2003). Case Study on the Development and Implementation of Guidelines for the Control of Illegal Logging with a View to Sustainable Forest Management in Peru.)

- S2CID 5711915.[permanent dead link]

- ^ James Owen, "World's Forests Rebounding, Study Suggests". National Geographic News, 13 November 2006.

- PMID 37481639.

- ^ "Forest Holocaust". National Geographic. Archived from the original on 22 April 2009. Retrieved 16 October 2008.

- ^ IUCN – Three new sites inscribed on World Heritage List Archived 14 January 2009 at the Wayback Machine, 27 June 2007.

- ^ "Madagascar's rainforest map". New Scientist. Archived from the original on 20 September 2016. Retrieved 26 August 2017.

- ^ "THE SIZE OF THE RAINFORESTS". csupomona.edu. Archived from the original on 30 September 2012.

- ^ Chart – Tropical Deforestation by Country & Region. Mongabay.com. Retrieved 4 December 2011.

- ^ Rainforest Destruction. rainforestweb.org

- ^ The Amazon Rainforest, BBC, 14 February 2003.

- ^ Schlanger, Zoë; Wolfe, Daniel (21 August 2019). "The fires in the Amazon were likely set intentionally". Quartz. Retrieved 22 August 2019.

- ^ Mackintosh, Eliza (23 August 2019). "The Amazon is burning because the world eats so much meat". CNN. Retrieved 23 August 2019.

- ^ Liotta, Edoardo (23 August 2019). "Feeling Sad About the Amazon Fires? Stop Eating Meat". Vice. Retrieved 30 August 2019.

- ^ Revington, John. "The Causes of Tropical Deforestation". New Renaissance Magazine.

- ^ "What is Deforestation?". kids.mongabay.com.

- ^ "Brazil registers huge spike in Amazon deforestation". Deutsche Welle. 3 July 2019.

- ^ Amazon deforestation rises sharply in 2007, USATODAY.com, 24 January 2008.

- ^ Vidal, John (31 May 2005). "Rainforest loss shocks Brazil". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 1 April 2010.

- ^ "Paraguay es principal deforestador del Chaco". ABC Color newspaper, Paraguay. Retrieved 13 August 2011.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Paraguay farmland". Archived from the original on 18 September 2012. Retrieved 13 August 2011.

- ^ "Haiti Is Covered with Trees". EnviroSociety. Tarter, Andrew. 19 May 2016. Retrieved 14 November 2016.

- ^ Kinver, Mark (12 September 2019). "World 'losing battle against deforestation'". BBC News.

- ^ "Analysis: The next Amazon? Congo Basin faces rising deforestation threat". Reuters. 11 November 2022.

- ^ a b "The World's 10 Most Threatened Forest Hotspots". Conservation.org. Conservation International. 2 February 2011. Archived from the original on 5 February 2011.

- ^ ISBN 9781009157926.

- PMID 26601154.

- ^ Indo-Burma, Conservation International.

- ^ New Caledonia, Conservation International.

- ^ Sundaland, Conservation International.

- ^ Philippines, Conservation International.

- ^ Atlantic Forest Archived 12 December 2011 at the Wayback Machine, Conservation International.

- ^ Mountains of Southwest China, Conservation International.

- ^ California Floristic Province Archived 14 April 2011 at the Wayback Machine, Conservation International.

- ^ Coastal Forests of Eastern Africa, Conservation International.

- ^ Madagascar & Indian Ocean Islands, Conservation International.

- ^ Eastern Afromontane, Conservation International.

- ^ "Government Subsidies for Agriculture May Exacerbate Deforestation, says new UN report". United Nations Sustainable Development. 3 September 2015. Archived from the original on 3 August 2016. Retrieved 10 July 2021.

- PMID 30213911.

- ^ Starkel, Leszek (2018). "Role Of Climatic And Anthropogenic Factors Accelerating Soil Erosion And Fluvial Activity In Central Europe" (PDF). Studia Quaternaria. 22.

- PMID 27100667.

- ^ "Cattle ranching in the Amazon rainforest". www.fao.org. Retrieved 25 February 2020.

- ^ "Growth of Brazil's Beef Industry Fueling Fires Destroying Amazon Rainforest". KTLA. 23 August 2019. Retrieved 25 February 2020.

- ^ "slash-and-burn agriculture | Definition & Impacts". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 28 April 2020.

- ^ "What is Slash and Burn Agriculture". World Atlas. Retrieved 28 April 2020.

- ^ "Deforestation and Climate Change". Archived from the original on 15 March 2023. Retrieved 28 September 2023.

- ISSN 1877-3435.

- ISSN 0167-8809.

- ^ Wang, George C. (9 April 2017). "Go vegan, save the planet". CNN. Retrieved 25 August 2019.

- ^ Liotta, Edoardo (23 August 2019). "Feeling Sad About the Amazon Fires? Stop Eating Meat". Vice. Retrieved 25 August 2019.

- ISBN 978-92-5-105571-7. Retrieved 19 August 2008.

- ISBN 0-8213-5691-7. Archived (PDF) from the original on 10 September 2008. Retrieved 4 September 2008.)

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help - ^ "Unsustainable Cattle Ranching". World Wildlife Fund. Retrieved 22 October 2022.

- ^ "How cattle ranches are chewing up the Amazon rainforest | Greenpeace UK". Greenpeace UK. 31 January 2009. Retrieved 29 April 2018.

- ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 28 April 2020.

- S2CID 251429424.

- ^ "Rates of Deforestation & Reforestation in the U.S." Retrieved 11 April 2018.

- ^ "Logging | Global Forest Atlas". globalforestatlas.yale.edu. Archived from the original on 5 June 2019. Retrieved 28 April 2020.

- ^ PMID 12322119.

- doi:10.1016/S0006-3207(99)00088-9. Archived from the original(PDF) on 8 September 2006.

- ^ Burgonio, T.J. (3 January 2008). "Corruption blamed for deforestation". Philippine Daily Inquirer.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "WRM Bulletin Number 74". World Rainforest Movement. September 2003. Archived from the original on 4 October 2008. Retrieved 17 October 2008.

- hdl:10419/258237.

- ^ "Global Deforestation". Global Change Curriculum. University of Michigan Global Change Program. 4 January 2006. Archived from the original on 15 June 2011.

- ^ a b Marcoux, Alain (August 2000). "Population and deforestation". SD Dimensions. Sustainable Development Department, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). Archived from the original on 28 June 2011.

- ^ Butler, Rhett A. "Impact of Population and Poverty on Rainforests". Mongabay.com / A Place Out of Time: Tropical Rainforests and the Perils They Face. Retrieved 13 May 2009.

- ^ a b Stock, Jocelyn; Rochen, Andy. "The Choice: Doomsday or Arbor Day". umich.edu. Archived from the original on 16 April 2009.

- ^ Ehrhardt-Martinez, Karen. "Demographics, Democracy, Development, Disparity and Deforestation: A Crossnational Assessment of the Social Causes of Deforestation". Paper presented at the annual meeting of the American Sociological Association, Atlanta Hilton Hotel, Atlanta, GA, 16 August 2003. Archived from the original on 10 December 2008. Retrieved 13 May 2009.

- ^ "Urbanisation | DEFORESTATION IN SOUTHEAST ASIA". blogs.ntu.edu.sg. Retrieved 1 November 2022.

- .

- ^ "The Double Edge of Globalization". YaleGlobal Online. Yale University Press. June 2007.

- ^ Butler, Rhett A. "Human Threats to Rainforests—Economic Restructuring". Mongabay.com / A Place Out of Time: Tropical Rainforests and the Perils They Face. Retrieved 13 May 2009.

- doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2005.09.005. Archived from the original(PDF) on 29 October 2008. Retrieved 17 October 2008.

- ^ (PDF) from the original on 11 May 2008.

- doi:10.1139/x99-225.

- (PDF) from the original on 11 December 2009.

- ISBN 0-231-13195-X

- S2CID 52273353.

- (PDF) from the original on 15 August 2017.

- ^ .

- Forests and the European Union Resource Network. 17 March 2015. Archived from the original(PDF) on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 31 March 2015.

- doi:10.1016/j.ecolecon.2006.03.014. Archived from the original(PDF) on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 8 December 2018.

- ^ Whitehead, John (22 November 2006) Environmental Economics: A deforestation Kuznets curve?, env-econ.net .

- .

- ^ EXTRACTED FORESTS UNEARTHING THE ROLE OF MINING-RELATED DEFORESTATION AS A DRIVER OF GLOBAL DEFORESTATION (PDF). World Wildlife Fund. 2023. pp. 3, 6, 7, 22. Retrieved 23 April 2023.

- ^ PMID 35831499.

- News article: "Forests are becoming less resilient because of climate change". New Scientist. Retrieved 21 August 2022.

- .

- ^ Seymour, Frances; Gibbs, David (8 August 2019). "Forests in the IPCC Special Report on Land Use: 7 Things to Know". World Resources Institute. Retrieved 20 March 2020.

- ^ Harris, Nancy; Dow Goldman, Elizabeth; Weisse, Mikaela; Barrett, Alyssa (13 September 2018). "When a Tree Falls, Is It Deforestation?". World Resources Institute. Retrieved 30 August 2019.

- ^ Dapcevich, Madison (28 August 2019). "Disastrous Wildfires Sweeping Through Alaska Could Permanently Alter Forest Composition". Ecowatch. Retrieved 30 August 2019.

- JSTOR 2388278.

- ^ Higa, Takejiro. Battle of Okinawa Archived 20 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine, The Hawaii Nisei Project

- ^

Arreguín-Toft, Ivan (8 December 2005). How the Weak Win Wars: A Theory of Asymmetric Conflict. Cambridge Studies in International Relations ISSN 0959-6844. Vol. 99. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 61. ISBN 9780521839761. Retrieved 17 June 2018.

[...] Voronzov [...] then set about organizing a more methodical destruction of Shamil and the subsequent conquest of the Caucasus. Over the next decade, this involved nothing more complicated or less deadly than the deforestation of Chechnia.

- ^ "DEFOLIANT DEVELOPED BY US WAS FOR KOREAN WAR". States News Services. 29 May 2011.

- ^ Pesticide Dilemma in the Third World: A Case Study of Malaysia. Phoenix Press. 1984. p. 23.

- ISBN 978-0-415-93732-0.

- ^

Marchak, M. Patricia (18 September 1995). Logging the globe. McGill-Queen's Press – MQUP. pp. 157–. ISBN 978-0-7735-1346-4. Retrieved 4 December 2011.

- ISBN 978-0-8203-3827-9.

- S2CID 144885326.

- SSRN 4072727.

- ^ ISSN 2624-893X.

- ^ S2CID 247160560.

- FAO

- ^ "Tropical Deforestation and Global Warming | Union of Concerned Scientists". www.ucsusa.org. Retrieved 1 November 2022.

- .

...land use change, particularly deforestation (driven by agricultural land expansion and wood demand), has also been one of the major contributors to climate change.

- S2CID 129188479.

- ^ "Deforestation emissions far higher than previously thought, study finds". The Guardian. 28 February 2022. Retrieved 16 March 2022.

- ^ "Forests help reduce global warming in more ways than one". Science News. 24 March 2022. Retrieved 19 April 2022.

- doi:10.1890/03-5225.

- ^ doi:10.1016/j.envsci.2007.01.010. Archived from the original(PDF) on 18 January 2012.

- PMID 36623189.

- S2CID 130116768.

- ^ Nafeez, Ahmed (28 July 2020). "Theoretical Physicists Say 90% Chance of Societal Collapse Within Several Decades". Vice. Retrieved 9 August 2020.

- PMID 32376879.

- ^ "Underlying Causes of Deforestation". UN Secretary-General’s Report. Archived from the original on 11 April 2001.

- ^ Rogge, Daniel. "Deforestation and Landslides in Southwestern Washington". University of Wisconsin-Eau Claire.

- ^ China's floods: Is deforestation to blame? BBC News. 6 August 1999.

- ISBN 0471704385.

- ^ Hongchang, Wang (1 January 1998). "Deforestation and Desiccation in China A Preliminary Study". In Schwartz, Jonathan Matthew (ed.). The Economic Costs of China's Environmental Degradation: Project on Environmental Scarcities, State Capacity, and Civil Violence, a Joint Project of the University of Toronto and the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. Committee on Internat. Security Studies, American Acad. of Arts and Sciences. Archived from the original on 30 December 2009.

- ^ ISBN 978-8121929370.

- ^ "Soil, Water and Plant Characteristics Important to Irrigation". North Dakota State University.

- .

- ^ a b "How can you save the rain forest. 8 October 2006. Frank Field". The Times. London. 8 October 2006. Retrieved 1 April 2010.

- ^ "Deforestation as a major threat". Daily Sun (Opinion). Retrieved 26 February 2022.

- ISBN 9781405144674.

- ^ ]

- ^ a b c "Deforestation of sandy soils a greater threat to climate change". YaleNews. 1 April 2014. Retrieved 9 February 2018.

- ^ S2CID 8361418.

- ^ Rebecca, Lindsey (30 March 2007). "Tropical Deforestation: Feature Articles". earthobservatory.nasa.gov. Retrieved 9 February 2018.

- ^ Nilsson, Sten (March 2001). Do We Have Enough Forests? Archived 7 June 2019 at the Wayback Machine, American Institute of Biological Sciences.

- ^ doi:10.1130/G31182.1.

- ^ Lewis, Sophie (9 September 2020). "Animal populations worldwide have declined by almost 70% in just 50 years, new report says". CBS News. Retrieved 10 September 2020.

The report points to land-use change — in particular, the destruction of habitats like rainforests for farming — as the key driver for loss of biodiversity, accounting for more than half of the loss in Europe, Central Asia, North America, Latin America and the Caribbean.

- ^ Rainforest Biodiversity Shows Differing Patterns, ScienceDaily, 14 August 2007.

- ^ "Medicine from the rainforest". Research for Biodiversity Editorial Office. Archived from the original on 6 December 2008.

- ^ Single-largest biodiversity survey says primary rainforest is irreplaceable Archived 14 August 2009 at the Wayback Machine, Bio-Medicine, 14 November 2007.

- ^ Tropical rainforests – The tropical rainforest, BBC

- ^ Tropical Rain Forest. thinkquest.org

- ^ U.N. calls on Asian nations to end deforestation Archived 24 September 2015 at the Wayback Machine, Reuters, 20 June 2008.

- ^ "Facts and information on the Amazon Rainforest". www.rain-tree.com.

- ^ Tropical rainforests – Rainforest water and nutrient cycles Archived 13 February 2009 at the Wayback Machine, BBC

- ^ Butler, Rhett A. (2 July 2007) Primary rainforest richer in species than plantations, secondary forests, mongabay.com,

- ^ Flowers, April. "Deforestation in the Amazon Affects Microbial Life As Well As Ecosystems". Science News. Redorbit.com. Archived from the original on 2 May 2013. Retrieved 12 March 2013.

- ^ Rainforest Facts. Rain-tree.com (20 March 2010). Retrieved 29 August 2010.

- ISBN 0-385-46809-1.

- ^ The great rainforest tragedy Archived 12 September 2011 at the Wayback Machine, The Independent, 28 June 2003.

- ^ Biodiversity wipeout facing South East Asia, New Scientist, 23 July 2003.

- ^ S2CID 35154695.

- S2CID 35154695.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-412-45520-9.

- ^ Sohn, Emily (12 July 2012). "More extinctions expected in Amazon". Discovery. Archived from the original on 7 November 2012. Retrieved 13 July 2012.

- ^ Broeker, Wallace S. (2006). "Breathing easy: Et tu, O2". Columbia University

- S2CID 153481315.

- S2CID 85214078.

- ^ a b Biodiversity and Infectious Diseases Archived 12 May 2016 at the Wayback Machine, Center for Health and the Global Environment, Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, Harvard University (last accessed 15 May 2017).

- ^ "UN Decade on Ecosystem Restoration".

- ^ "New UN Decade on Ecosystem Restoration offers unparalleled opportunity for job creation, food security and addressing climate change". Archived from the original on 23 June 2022. Retrieved 9 December 2020.

- S2CID 240645073.

- PMID 22761706.

- ^ Deforestation and emerging diseases | Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. Thebulletin.org (15 February 2011). Retrieved 13 November 2016.

- PMID 11938496.

- ^ African Politics Portal | Tag Archive | Environmental impact of deforestation in Kenya Archived 13 April 2016 at the Wayback Machine. African-politics.com (28 May 2009). Retrieved 13 November 2016.

- ^ 2014 Kenya Economic Survey Marks Malaria As Country’s Leading Cause Of Death | The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation. Kff.org (1 May 2014). Retrieved 13 November 2016.

- PMID 29557569.

- PMID 25354270.

- ^ Deforestation sparks giant rodent invasions. News.mongabay.com (15 December 2010). Retrieved 13 November 2016.

- ^ Quaglia, Sofia (17 December 2021). "Deforestation making outdoor work unsafe for millions, says study". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 17 December 2021. Retrieved 18 December 2021.

- S2CID 244068407.

- ^ S2CID 227181993. Retrieved 18 October 2022.

- ^ Outbreak Readiness and Business Impact Protecting Lives and Livelihoods across the Global Economy (PDF). World Economic Forum, Harvard Global Health Institute. January 2019. p. 7. Archived (PDF) from the original on 21 January 2019. Retrieved 12 March 2020.

- ISBN 978-92-807-3553-6. Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 February 2017. Retrieved 1 May 2020.

Text was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

Text was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License - ^ Carrington, Damian (17 June 2020). "Pandemics result from destruction of nature, say UN and WHO". The Guardian. Retrieved 18 June 2020.

- ^ "Science points to causes of COVID-19". United Nations Environmental Programm. United Nations. 22 May 2020. Retrieved 2 June 2020.

- ^ "World Bank: Brazil faces $317 billion in annual losses to Amazon deforestation". 8.9ha. World Bank. 24 May 2023. Retrieved 30 May 2023.

- ^ "Destruction of Renewable Resources". rainforests.mongabay.com.

- ^ "Global Forest Change – Google Crisis Map". Google Crisis Map. Retrieved 12 October 2016.

- PMID 27708330.

- ^ Earth Observatory. NASA Tropical Deforestation Research. Archived 2009-11-23 at the Wayback Machine accessed 12 November 2009.

- ^ The world’s last intact forest landscapes. intactforests.org

- ^ "World Intact Forests campaign by Greenpeace". intactforests.org. Archived from the original on 28 February 2009. Retrieved 10 July 2008.

- ^ The World's Forests from a Restoration Perspective, WRI

- ^ "Alternative thematic map by Howstuffworks; in pdf" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 July 2009. Retrieved 6 April 2009.

- ^ "29. Policies, strategies and technologies for forest resource protection – William B. Magrath* and Richard Grandalski**". www.fao.org. Retrieved 2 May 2021.

- ISSN 0305-750X.

- .

- S2CID 152365403.

- S2CID 206553761.

- ISSN 0959-3780.

- ISSN 0959-3780.

- S2CID 239890357.

- ^ "200 million acres of forest cover have been lost since 1960". Grist. 5 August 2022. Retrieved 15 September 2022.

- ISSN 1748-9326.

- ^ Schröder, André (15 September 2022). "European bill passes to ban imports of deforestation-linked commodities". Mongabay. Retrieved 18 September 2022.

- ^ "Council adopts new rules to cut deforestation worldwide". European Counsil. European Union. Retrieved 22 May 2023.

- ^ Téllez Chávez, Luciana (16 May 2023). "EU Approves Law for 'Deforestation-Free' Trade". Human Rights Watch. Retrieved 22 May 2023.

- ^ 'Bankrolling ecosystem destruction - The EU must stop the cash flow to businesses destroying nature'

- ^ Bankrolling nature destruction

- ^ "COP26: World leaders promise to end deforestation by 2030". BBC News. 2 November 2021.

- ^ a b c Rhett A. Butler (5 November 2021). "What countries are leaders in reducing deforestation? Which are not?". Mongabay.

- ^ a b c d e Jake Spring; Simon Jessop (3 November 2021). "Over 100 global leaders pledge to end deforestation by 2030". Reuters.

- ^ "Glasgow Leaders' Declaration on Forests and Land Use". 2021 United Nations Climate Change Conference. 12 November 2021. Archived from the original on 14 November 2021.

- ^ Rankin, Jennifer (17 November 2021). "EU aims to curb deforestation with beef and coffee import ban". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 17 November 2021. Retrieved 17 November 2021.

- ^ Petrequin, Samuel (13 September 2022). "EU lawmakers support ban of goods linked to deforestation". AP NEWS. Retrieved 14 September 2022.

- ^ Holder, Michael (10 December 2018). "'Potential breakthrough': Palm oil giant Wilmar steps up 'no deforestation' efforts". Business Green. Retrieved 11 December 2018.

- ^ "Major shifts in private finance, trade and land rights to protect world's forests". GOV.UK. 2 November 2021. Archived from the original on 2 November 2021. Retrieved 7 November 2021.

- ^ "Indigenous Peoples' Forest Tenure". Project Drawdown. 6 February 2020. Retrieved 13 September 2020.

- ^ a b "India should follow China to find a way out of the woods on saving forest people". The Guardian. 22 July 2016. Retrieved 7 August 2016.

- ^ a b "China's forest tenure reforms". rightsandresources.org. Archived from the original on 23 September 2016. Retrieved 7 August 2016.

- ^ "The bold plan to save Africa's largest forest". BBC. 7 January 2021. Retrieved 16 September 2021.

- ISBN 0-14-311700-9.

- ISBN 0-14-311700-9.

- ^ Rosenberg, Tina (13 March 2012). "In Africa's vanishing forests, the benefits of bamboo". The New York Times. Retrieved 26 July 2012.

- ^ "State of the World's Forests 2009". United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization.

- ^ Wertz-Kanounnikoff, Sheila; Alvarado, Rubio; Ximena, Laura. "Why are we seeing "REDD"?". Institute for Sustainable Development and International Relations. Archived from the original on 25 December 2007. Retrieved 14 November 2016.

- ^ "Copenhagen Accord of 18 December 2009" (PDF). UNFCC. 2009. Archived (PDF) from the original on 31 January 2010. Retrieved 28 December 2009.

- ^ Forest Monitoring for Action (FORMA) : Center for Global Development : Initiatives: Active. Cgdev.org (23 November 2009). Retrieved 29 August 2010.

- ^ Browser – GEO FCT Portal[permanent dead link]. Portal.geo-fct.org. Retrieved 29 August 2010.

- ^ "Methodological Guidance" (PDF). UNFCC. 2009. Archived (PDF) from the original on 19 January 2010. Retrieved 28 December 2009.

- ^ Agriculture Secretary Vilsack: $1 billion for REDD+ "Climate Progress Archived 8 June 2010 at the Wayback Machine. Climateprogress.org (16 December 2009). Retrieved 29 August 2010.

- ISBN 9780757001444.

- ^ ISBN 0-7301-0422-2.

- .

- ^ "hand tool: Neolithic tools". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. 19 June 2023.

- ^ "Neolithic Age from 4,000 BC to 2,200 BC or New Stone Age". www.archaeolink.co.uk. Archived from the original on 4 March 2007. Retrieved 2 October 2008.

- ^ Hogan, C. Michael (22 December 2007). "Knossos fieldnotes", The Modern Antiquarian

- ISBN 9780295750903.

- ISBN 9780295747330.

- (PDF) from the original on 29 May 2013.

- ^ "Miletus". The Byzantine Legacy. Retrieved 22 November 2022.

- ^ "Miletus (Site)". www.perseus.tufts.edu. Retrieved 22 November 2022.

- ^ "The Mystery of Easter Island", Smithsonian Magazine, 1 April 2007.

- ^ "Historical Consequences of Deforestation: Easter Island (Diamond 1995)". mongabay.com. Archived from the original on 29 April 2009. Retrieved 8 July 2008.

- ^ "Jared Diamond, Easter Island's End". hartford-hwp.com.

- ISBN 9789380228488.

- ^ Chew, Sing C. (2001). World Ecological Degradation. Oxford, England: AltaMira Press. pp. 69–70.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-4438-6706-1.

- .

- ^ "War, Plague No Match For Deforestation in Driving CO2 Buildup". Carnegie Institution for Science. 20 January 2011. Retrieved 22 November 2019.

- Wikidata Q106515792.

- S2CID 130658356.

- ISSN 1040-6182.

- ISBN 978-1-883982-15-7.

- ISBN 978-81-260-0086-9.

- ^ Datta, Bīrendranātha; Śarmā, Nabīnacandra (1994). A Handbook of Folklore Material of North-East India. India: Anundoram Borooah Institute of Language, Art & Culture, Assam. p. 356.

- ISBN 978-81-87502-02-9.

Further reading

- Balboni, Clare, et al. "The economics of tropical deforestation." Annual Review of Economics 15 (2023): 723-754. online

- Myers, Norman. "Tropical deforestation: rates and patterns." in The causes of tropical deforestation (2023): 27-40.

- Pendrill, Florence, et al. "Disentangling the numbers behind agriculture-driven tropical deforestation." Science 377.6611 (2022): eabm9267. online

- Ritchie, Hannah, and Max Roser. "Deforestation and forest loss." Our world in data (2023). online

- Schleifer, Philip. Global Shifts: Business, Politics, and Deforestation in a Changing World Economy (MIT Press, 2023) ISBN 978-0-262-54553-2.online book review

Sources

![]() This article incorporates text from a free content work. Licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 (license statement/permission). Text taken from Global Forest Resources Assessment 2020 Key findings, FAO, FAO.

This article incorporates text from a free content work. Licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 (license statement/permission). Text taken from Global Forest Resources Assessment 2020 Key findings, FAO, FAO.

![]() This article incorporates text from a free content work. Licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 IGO (license statement/permission). Text taken from The State of the World’s Forests 2020. Forests, biodiversity and people – In brief, FAO & UNEP, FAO & UNEP.

This article incorporates text from a free content work. Licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 IGO (license statement/permission). Text taken from The State of the World’s Forests 2020. Forests, biodiversity and people – In brief, FAO & UNEP, FAO & UNEP.

External links

- Global map of deforestation based on Landsat data

- Old-growth forest zones within the remaining world forests

- OneWorld Tropical Forests Guide Archived 22 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- General info on deforestation effects Archived 18 April 2021 at the Wayback Machine

- Deforestation and Climate Change

- Ritchie, Hannah; Roser, Max (9 February 2021). "Drivers of Deforestation". Our World in Data.